South Dakota rejects federal food funding despite 25,000 children going hungry

“Federal money often comes with strings attached, and more of it is often not a good thing."

At a time when an estimated 25,000 South Dakota children struggle with hunger, the state decided against applying for a federal program that would have provided $7.5 million to feed low-income kids this summer.

The federal funding was available through a program called Pandemic Electronic Benefits Transfer (P-EBT). It would have helped an estimated 63,000 South Dakota children receive healthy food during summer 2023.

The U.S. Department of Agriculture funding effort began during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic in 2020. Congress recently approved it as a permanent program.

The extension was seen as a victory for families and groups that advocate policies to keep children fed. Rather than requiring families or children to travel to specific meal sites to get food, the P-EBT program provides payment cards to families so they can purchase eligible healthy foods at any participating store at any time. According to program guidelines, the program would have provided about $40 in monthly food benefits (about $1.30 per day) to each qualifying child for three months in the summer.

Earlier from SD News Watch: More South Dakota students going hungry after federal free meal program ends

The offices of Gov. Kristi Noem and South Dakota Department of Education told News Watch the state is not applying because summer meal programs are already offered and it’s too challenging to administer the program.

That decision drew the ire of Sioux Falls advocate Cathy Brechtelsbauer, who has fought hunger for decades as leader of the organization Bread for the World.

“Our kids in South Dakota are missing out on $7.5 million worth of food, and it’s not like they’re necessarily getting it someplace else,” she said. “This is like taking food away from kids, and I hope we don’t want to be that kind of state.”

South Dakota is one of seven states that did not apply.

South Dakota previously took part in food program

Noem spokesman Ian Fury did not provide News Watch an interview with the governor but did send an email with a statement.

“Federal money often comes with strings attached, and more of it is often not a good thing,” Fury wrote. “Because of South Dakota’s record low unemployment rate, our robust existing food programs, and the administrative burden associated with running this program, we declined these particular federal dollars.”

When asked to explain the administrative challenges surrounding the program, Department of Education spokeswoman Nancy Van Der Weide said the state found it difficult to obtain enough information about children to administer the program effectively, even though the state did participate in Pandemic EBT in 2020 and 2021. DOE and the Department of Social Services were responsible for applying to the program.

“Implementing the program was difficult because South Dakota is a state that prioritizes local control more than most states,” Van Der Weide, who also declined an interview request, wrote to News Watch in an email.

“Because of this, information about individual students is not shared to state government entities en masse. This made it very difficult for the state government to get enough details to adequately administer the program.”

Brechtelsbauer was shocked that the state was rejecting federal money based on perceived challenges in administering the program.

“That just blows my mind,” she said. “How can we think like that when we’re talking about kids needing food? Why can’t we handle things as well as 43 other states?”

Thousands of meals provided each summer

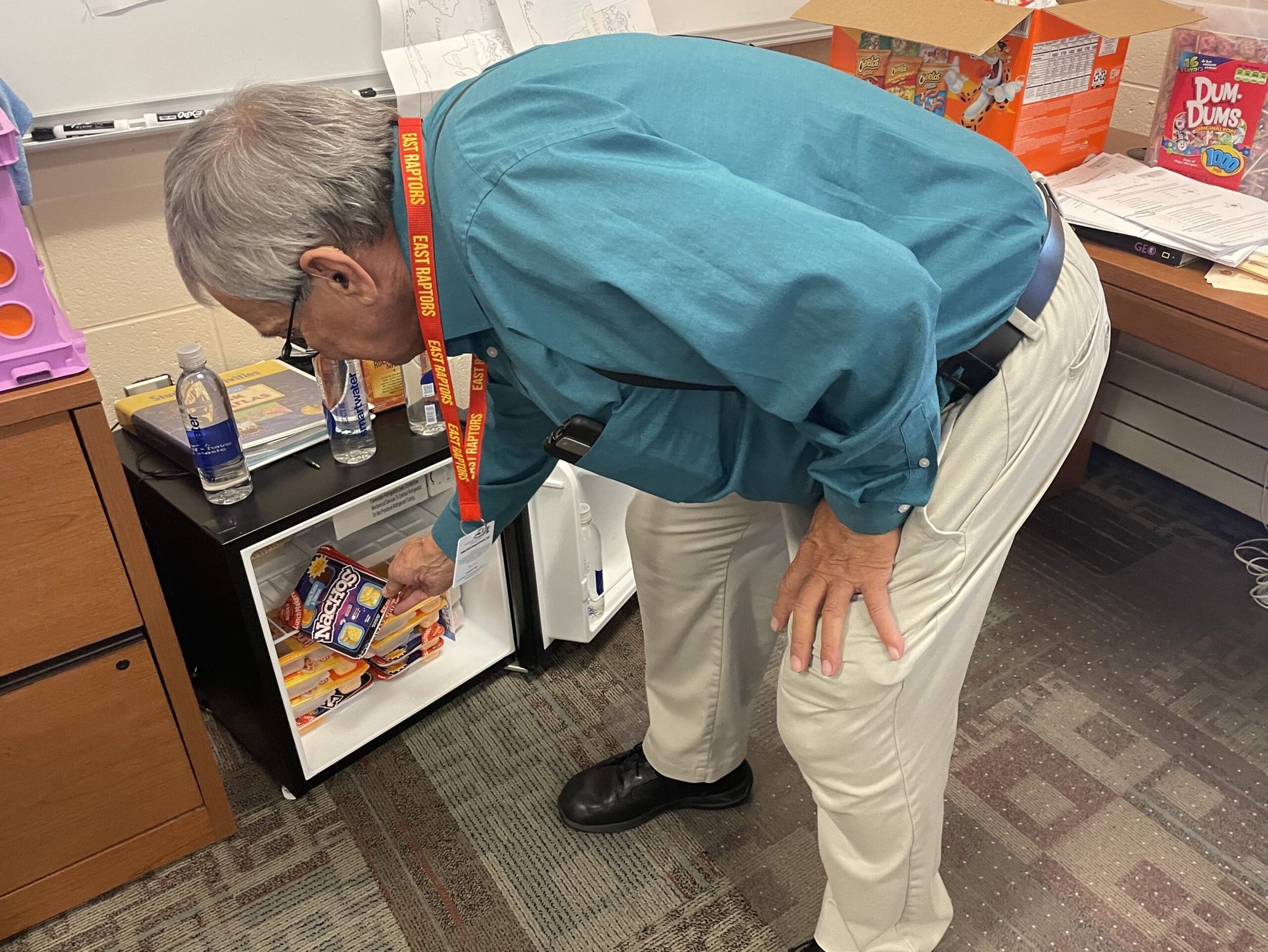

Van Der Weide pointed out that the South Dakota Summer Food Service Program provided children with more than 303,000 meals and about 20,500 snacks at 83 disbursement sites during summer 2022.

That federally funded summer meal program is part of a larger ecosystem of efforts to get food to children during the summer, including by statewide organizations such as Feeding South Dakota and local efforts run by Boys & Girls Clubs and other charitable organizations.

And yet, according to Feeding South Dakota, about 24,750 South Dakota children, or about 11% of the school-aged population, remained “food insecure” in the state in 2022.

The group defines food insecurity as “the consistent lack of food to have a healthy life because of your economic situation.”

Feeding South Dakota provided about 8,800 meals to children in Sioux Falls and Rapid City through its backpack program over 10 weeks this summer. It also offered food to needy people in 91 other communities through monthly visits by its mobile food unit, according to Stacey Andernacht, communications director for the nonprofit.

Van Der Weide did not answer a question posed by News Watch about whether the state would apply for P-EBT funding in coming years.

Hunger higher in rural and reservation areas

Finding the money to afford healthy food, at a time when prices for food and fuel are on the rise, is difficult everywhere but especially challenging in rural and reservation areas of the state, Andernacht told News Watch in an email.

“Rural communities do experience a higher food insecurity rate for many reasons – there are few grocery stores, transportation can be an issue, employment opportunities are less, and the logistics of getting food to these communities comes at a higher expense,” she wrote.

The increased federal funding for summer meals and provision of free meals to all public school students during the pandemic were effective at reducing hunger and food insecurity across the state, Andernacht said. Losing access to another food provision program could increase the hardship on South Dakota families struggling to make ends meet, she said.

When free meals for all public school students ended in fall 2022, the agency saw a 20% rise in usage of its mobile food pantries, which served roughly 13,000 families each month from July 2022 to June 2023, Andernacht said.

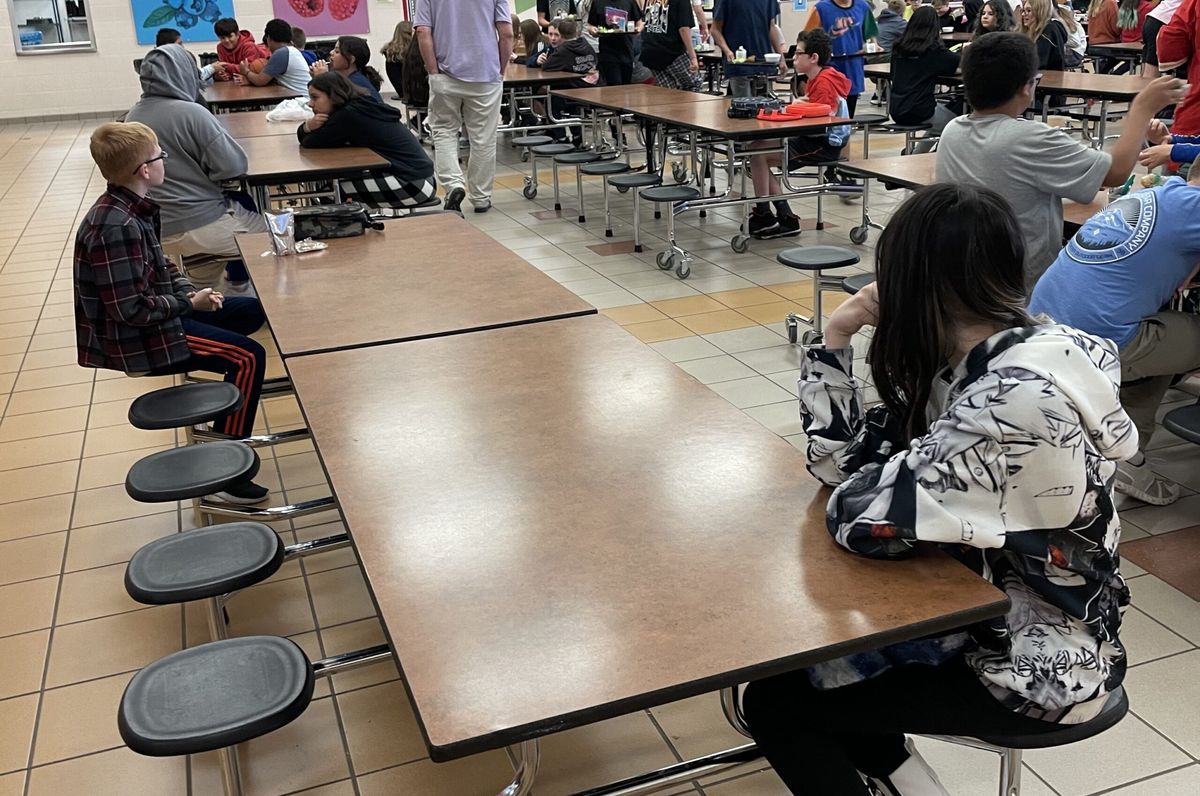

Students who qualify as low-income can still receive free or reduced-price meals at school. But the end of the pandemic free meal program caused many non-qualifying South Dakota children to go without meals at school or fall into arrears in trying to pay.

“We hear from those using our programs that without those pandemic-era benefits, and with the increasing inflation they are finding it difficult to afford household needs such as housing, utilities, and medication and also put food on their tables,” she wrote.

South Dakota received $80 million for food during COVID

South Dakota did participate in the Pandemic EBT food program in 2020 and 2021, when the program provided funding for meals during both school and non-school periods, according to federal records.

In spring 2020 the state received about $13.4 million and provided services to an estimated 47,000 students. In the 2020-21 school year, the state received about $36 million and served around 46,000 students in schools and daycares, records show. And in summer 2021, South Dakota received about $30 million and served around 79,000 students.

But the state did not participate in the program in summer 2022 or 2023, which has placed a greater burden on families and children already trying to fight off hunger, said Kelsey Boone, a policy analyst at the Food Research & Action Center, a group that battles hunger among adults and children.

“The general trends we’ve seen in the country, especially after emergency allotment nationwide ended, there has been an increase in food insecurity and decreasing allotments families get,” Boone said in an interview with News Watch.

Due to inflation and other ongoing transportation and financial hardships, it has become even more difficult for families to feed their children outside of the traditional school year, Boone said.

“On the child nutrition side of things, summer is the hungriest time of year for students,” she said. “Not having enough access to food is detrimental to physical health, development and well-being. And in the summer, it also leads to learning loss. Pandemic EBT has been a great burst of nutrition during the summer months, which is very beneficial to enhancing learning and growth.”

Flexibility to get food easier and helps beyond SNAP

The P-EBT program is also beneficial because it allows for flexible spending for qualifying low-income families beyond what they may receive in Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program benefits, Boone said. Furthermore, she said, the P-EBT program aids people who make slightly too much income to qualify for SNAP, formerly known as food stamps.

For families on SNAP, it gives them an extra cushion to be able to buy adequate food for the month,” Boone said. “For families that aren’t on SNAP, it still gives them a bit of extra wiggle room so they can go out and buy maybe an extra loaf of bread or something to tide them over.”

Tribal governments were not able to apply for Pandemic EBT funding but will be eligible under the new, expanded summer P-EBT program, Boone said.

“Expanding this program to those areas is going to be a game-changer for a lot of these individuals living on reservations and in rural communities,” she said.

“Having the availability of a nutrition benefit on an EBT card is going to be a lot easier and less of a burden on families than having to travel to a meal site.”

Pockets of poverty remain in rural South Dakota

Marcella Yellow Hammer knows firsthand the challenges that families in north-central South Dakota deal with in keeping their children fed.

Yellow Hammer, 76, runs the Boys & Girls Club of Standing Rock, a youth services facility that provides a safe place for youth in the McLaughlin area to have opportunities for education, recreation and — during the summer — a healthy breakfast or lunch.

For 10 weeks during the summer, the club serves meals to any child 18 and under who shows up during designated meal periods, Yellow Hammer said. Children are served milk, a fruit or vegetable and a healthy protein because many are unable to get a good meal at home.

“This is a very poverty-stricken area,” she said of the region just west of the Missouri River that is home to part of the Standing Rock Indian Reservation. “It’s one of the counties that has the greatest level of poverty in our homes.”

According to the U.S. Census, Corson County has the second-lowest median household income in South Dakota at roughly $38,000 a year. About 45% of the county population is under 18 years of age, and 42% of the population lives in poverty, the 2022 Census showed.

Single parents, hungry children

This summer, the club’s summer meals program has attracted up to 30 children a day, and yet the community need remains far from met, Yellow Hammer said.

“These parents are single mothers, single dads, single grandmothers, and many are not working,” she said.

During the school year, the club can serve food to children in first through sixth grades, though sometimes mothers bring in infants who are able to eat solid food to make sure they are fed.

Yellow Hammer said the free meals become even more important the further away families get from the 10th of each month, when they typically receive their reissued monthly food stamps.

The COVID-19 pandemic created even greater challenges to keeping children fed because more than 120 daily meals had to be cooked on a single residential stove and dropped off at individual homes each day, Yellow Hammer said.

Some children in the area suffer and may go hungry because their parents or caretakers are dealing with their own problems and do not prepare their children to leave the home to get a meal or are unable to provide them transportation to the club, she said.

Some children are allowed to stay up late and sleep well into the day, forcing them to miss meal times at the club, Yellow Hammer said.

When pandemic-era food funding was curtailed in 2022, Yellow Hammer said, all the difficulties in keeping low-income children in the area fed were compounded. Any federal funding the state could have qualified for would have helped families in the area served by the club, she said.

“Many of our families are out of food before the 10th of the month,” Yellow Hammer said. “I know one woman who told me, ‘My kids come to the Boys & Girls Club because if they stayed home, they wouldn’t have anything to eat, so they come to the club and get a meal, and I’m very thankful for it.’”