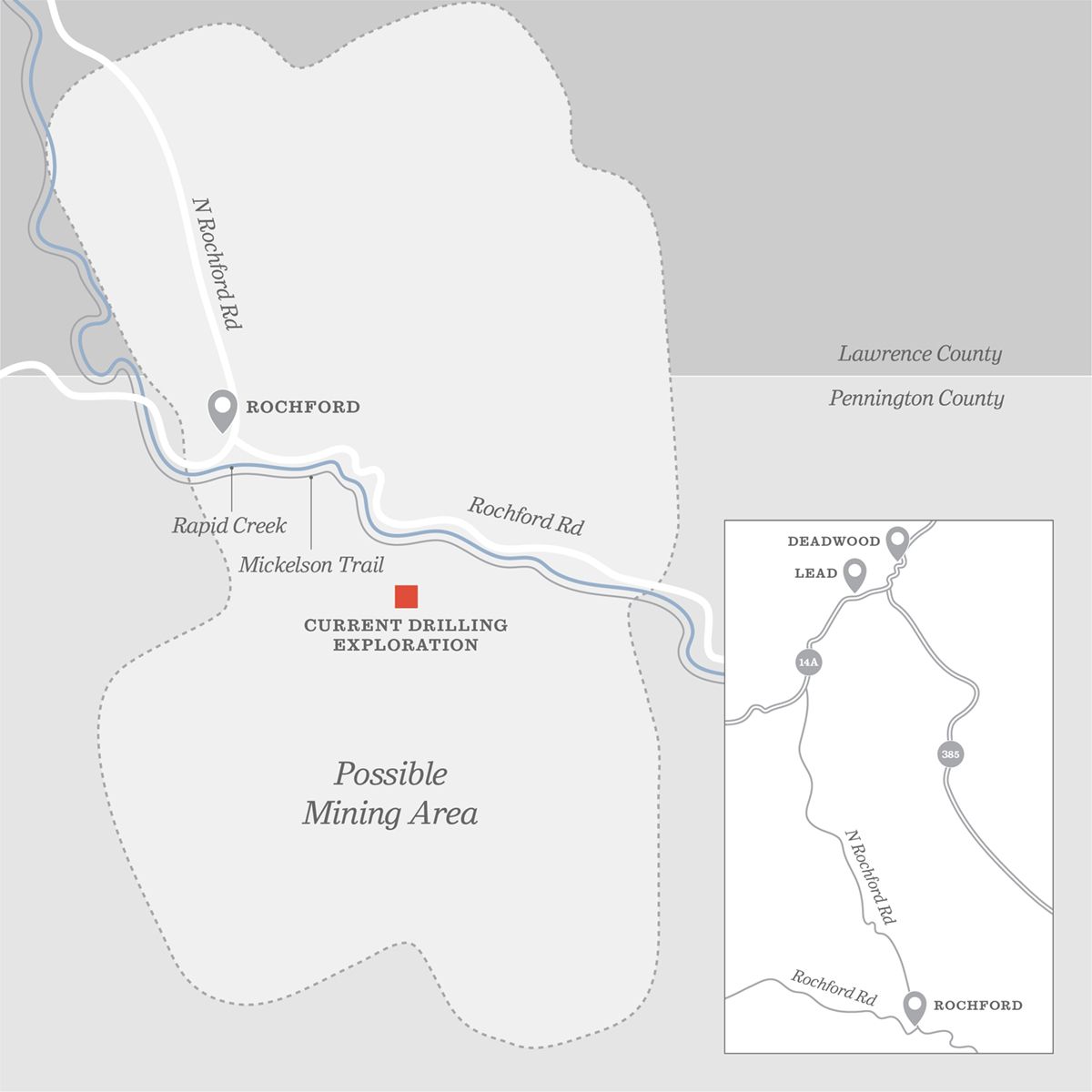

ROCHFORD, S.D. – One paved road leads in and out of Rochford, a remote Pennington County town that suddenly has become the center of a heated and growing debate over a proposal to mine for gold in a pristine part of the northern Black Hills.

With state permits in hand, a Canadian prospecting company has begun drilling exploratory holes just south of Rochford to test its theory that potentially historic quantities of top-grade gold may lie beneath the ponderosa pines and rocky hillsides around the town.

If gold is found, Mineral Mountain Resources of Vancouver foresees a future for Rochford in which the firm or another major mining company could remove millions of ounces of gold, putting it on scale with the famed Homestake Mine that operated in nearby Lead for more than a century. Company officials say they can explore safely and that mining can be done underground with minimal impact.

But the drilling and potential for mining have set off a wave of opposition and protest. One Rochford resident has joined environmentalists and Native Americans who fear the drilling and mining could destroy a secluded section of the Black Hills, harm fish and wildlife, and foul Rapid Creek, which provides fresh water to Rapid City.

Protesters held a march opposing the drilling and three members of the Cheyenne River Tribe filed a lawsuit to block further exploration. In remarks to federal officials, Oglala Sioux Tribe President Scott Weston warned that “a war” with “bloodshed” may be waged if drilling continues.

Quiet town, loud protests

In many ways, the town of Rochford, population 8, epitomizes the character of the northern Black Hills of South Dakota.

The air is crisp and smells pleasantly of pine. Towering ridges encircle the almost uninhabited downtown. Bicyclists dodge deer when pedaling the Mickelson Trail that rolls like a ribbon alongside Rapid Creek. Fly rods are more or less mandatory.

There’s no cell phone service, no gas station, no grocery store. The only touristy touch is the iconic burger-and-beer hangout known as Moonshine Gulch Saloon, which serves locals, outdoor enthusiasts and the bikers who trek to scenic Rochford during the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally every August.

For a growing cadre of environmentalists and Native Americans, it’s unthinkable that the town and pristine hills around it could be considered the site of a huge new gold mine.

One opponent has already noticed signs of industrial activity around Rochford, such as widened forest roads and increased truck traffic. Many in the increasingly vocal opposition say mining could spoil the land, desecrate sacred Native sites, and contaminate the water of Rapid Creek which flows to Pactola Reservoir and makes up part of the drinking water supply for Rapid City.

“There’s absolutely no reason to destroy this,” said John Hopkins, a Rochford resident. “It’s beautiful, it’s sacred, it’s irreplaceable.”

In company materials online, Mineral Mountain said the Rochford claim could become “another Homestake,” a reference to one of the world’s most productive gold mines and an enterprise that shaped the cities of Lead and Deadwood just 20 miles north of Rochford.

The reference may have helped the company raise money for exploration, but the mere mention of Homestake has heightened the fear of opponents.

They envision another open-pit gold mine in their beloved Black Hills, not unlike Homestake’s roughly square-mile, 1,250-foot deep pit that is now the dominant physical feature in downtown Lead.

Mineral Mountain CEO Nelson Baker, however, dismisses that idea. Baker said the depth and type of gold he expects to find in Rochford does not lend itself to an open cut-type mine, but rather an underground operation whose only visible above-ground feature would be a mineshaft opening.

“There’s no way we would consider putting an open pit in Rochford,” Baker said, noting that open pit mines typically produce lower-quality gold than underground operations.

However, Baker cannot guarantee what another mining company could do if Mineral Mountain sold its claims, though in an email he stated: “I assure you that, even if we turn this project over to a third party, there is no economic reason to consider an open pit scenario.”

Even though Homestake produced 40 million ounces of gold, created thousands of jobs and helped build the Lead-Deadwood region during its 126-year history, the mine also took a toll on the environment.

“There’s absolutely no reason to destroy this. It’s beautiful, it’s sacred, it’s irreplaceable.” – John Hopkins, Rochford resident.

According to a 1971 study by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, Homestake discharged 312 pounds of cyanide and 2,700 pounds of suspended solids daily into a tributary of Whitewood Creek, which flows into the Belle Fourche River. The agency estimated that historically more than 270,000 tons of arsenic from Homestake were discharged into the creek. In 1981, an 18-mile section of Whitewood Creek was declared an EPA Superfund site that took 15 years to remediate.

About seven miles east of Lead, the Gilt Edge Mine remains one of only two EPA Superfund sites in South Dakota. The EPA and state of South Dakota have spent more than $105 million over the past two decades to clean up arsenic, cadmium, chromium, copper and lead contamination present when Canadian-based Brohm Mining declared bankruptcy and abandoned the mine in 1999. The company left behind 150 million gallons of acid-contaminated water in three open pits and millions of cubic yards of acid-generating rock, according to EPA documents.

Mineral Mountain has a blemish of its own in the Black Hills. The firm hired a contractor to drill exploratory holes near Keystone in the Central Black Hills from 2012-15. In November 2012, a torn liner at the drill site leaked a small amount of bentonite and other drilling fluids into Battle Creek. The spill was quickly contained and caused no significant damage to the creek, according to the South Dakota Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

The spill was an extremely rare event for Mineral Mountain, and the company changed contractors and began to use a sturdier liner after the leak, Baker said.

Only one major gold mine remains in operation in the northern Black Hills – the Wharf Mine, which operates an open-pit gold mine about four miles west of Lead. The mine, owned by Chicago-based Coeur Mining, employs about 215 people and produced more than 96,000 ounces of gold in 2017. According to a report by the International Cyanide Management Institute, the Wharf Mine uses cyanide in its gold separation processes and is fully in compliance with all safety regulations regarding the chemical.

Concerns over the potential for contamination of Rapid Creek and groundwater supplies have drawn the ire of groups that fight to protect water in western South Dakota. Their cause gained steam when a retired mining executive released a report that showed how water contaminated near Rochford could flow to Pactola Reservoir, one source of fresh water for Rapid City, in just 29 to 36 minutes.

The report by George “Duff” Kruse was titled “Save Rochford & Rapid Creek” and spawned a Facebook page of the same name. Kruse’s report contained frightening photos of other U.S. mining disasters paired with the phrase, “Is this what we want to happen to Rapid Creek and Rochford?”

Several Native American tribes are also fighting to stop the project, including the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, whose members filed a lawsuit in Pennington County court in February to stop the project. The suit alleges that Mineral Mountain illegally transferred its existing gold mining permit to a newly created South Dakota affiliate of Mineral Mountain.

Tribal members also say the proposed mining area is within a few miles from the Pe Sla lands, one of the Sioux Nation’s most sacred sites near Deerfield Lake. Four Sioux tribes paid $9 million for roughly 2,300 acres of land at Pe Sla, which means “Heart of Everything,” in 2012 and 2014.

The sacred opposition to mining is coupled with practical concerns for many tribal members. Carla Marshall of Rapid City, an enrolled member of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe, said that mining disrupts the natural world and puts the future of humankind at risk.

“For them to come in and start using that water and start drilling into Mother Earth, that disturbs the heavy metals that are encased in Mother Earth for a reason,” Marshall said. “The whole issue here is trying to protect our water for future generations, and that’s not just a Native issue.”

About 50 people, many Native American, held a protest march in Rochford in late February. Hopkins, the mine opponent, said law enforcement presence was heavy. Forest Service spokesman Scott Jacobson said state officers and sheriff’s deputies were present for the march.

Jacobson said Forest Service officials have been meeting with tribal leaders to hear their concerns and explain details of the permit application to drill on public land, which remains under review. The agency has received more than 100 public comments regarding the application, he said.

“Our eyes are wide open,” he said. “We’re just trying to make sure there’s dialogue and conversation.”

Authorities may have reason to be concerned given the lengthy environmental protests over the Dakota Access Pipeline in North Dakota in 2016, and the recent comment by tribal president Weston.

“You will have war if this happens,” Weston told Forest Service officials, according to a report in the Native Sun News Today newspaper that was confirmed by Jacobson. “There will be bloodshed because we have to stand up for our children and our grandchildren.”

Firm promises safety

Mineral Mountain Resources, has purchased the mining claims to hunt for gold on 7,516 acres, or about 12 square miles. The firm obtained the necessary state permits and hired a Colorado company, First Drilling, to drill as many as 120 prospecting holes up to 4,000 feet deep at a dozen drilling sites just south of Rochford to test Mineral Mountain’s theory that gold is present in financially worthy amounts.

Mineral Mountain, which paid $250 for a state permit and put up a $20,000 bond, is pumping water for drilling from Rapid Creek just east of Rochford.

During the first phase of drilling now underway, Mineral Mountain plans to sink nine holes about 4 inches wide on private land to obtain core samples to check for gold. Each phase of drilling, if successful, may lead to further phases of drilling. Once the drilling is complete, the hole is closed and capped.

The firm has an application filed with the U.S. Forest Service to drill up to 21 exploratory holes on public land near Rochford. That application is pending and still under review, according to Jacobson.

According to its temporary water use permit with the DENR, the firm can use 200 gallons of water per minute, or roughly 300,000 gallons a day up to a total of 1.8 million gallons through May 1. When the temporary water permit expires, the firm must apply for a new permit.

Drilling is taking place 24 hours a day in 12-hour shifts. The drilling water is recirculated to optimize use and eventually deposited in an environmentally safe area, Baker said.

Mineral Mountain is led by Baker, a 75-year-old Canadian who obtained an environmental engineering degree from the South Dakota School of Mines in Rapid City in the late 1960s. Baker said he has been involved with exploration of 1,000 potential mine sites during his career. Mineral Mountain formed in 2010 and has conducted 20 mineral explorations, he said.

Baker said his company is committed to safety, following all state and federal regulations “to a T,” and to protection of the environment. He said the firm has already invested about $7 million to prospect in the Black Hills over the past five years, including about $2 million to buy mine claims near Rochford. The firm paid $500,000 to purchase the former Standby Gold Mine where it is starting its exploratory drilling.

The firm also spent $500,000 for a high-resolution aerial study of the Rochford topography that indicated the likely presence of gold and makes more than $100,000 in annual payments to the state of South Dakota to keep its mine claims registered.

Early indicators show the Rochford area holds substantial gold deposits, Baker said. He said the Homestake Mine likely would have mined the area if the price of gold had remained sustainable and if the company had not run into financial difficulties. But with gold prices hovering around $1,335 an ounce, and positive preliminary signs, exploration is worth the cost, he said.

If an economically feasible amount of gold is found, a major international mining company, such as Goldcorp of Canada or Newmont Mining of Colorado, would likely be sold the rights to establish and operate the mine, Baker said.

However, it could take more than a decade and upward of $300 million to make the mine a reality, Baker said.

But as the son of a prospector whose son, Brad, is also now a prospector with Mineral Mountain, Baker believes the gold is worth going after. “All my life, I’ve been exploring and looking for mineral deposits,” he said, “because for me it’s a passion.”

Baker said that zeal extends to his firm’s commitment to follow all applicable regulations and to the protection of natural resources, including returning drilled areas back to their natural state.

“We’re good corporate citizens and we’re just as much environmentalists as the locals are there,” Baker said, noting he has never before encountered such resistance to an exploration effort. “Rest assured we’re going to make absolutely sure we don’t destroy any land.”

Battle will go on

But promises from Baker will not satisfy fierce project opponents like Hopkins.

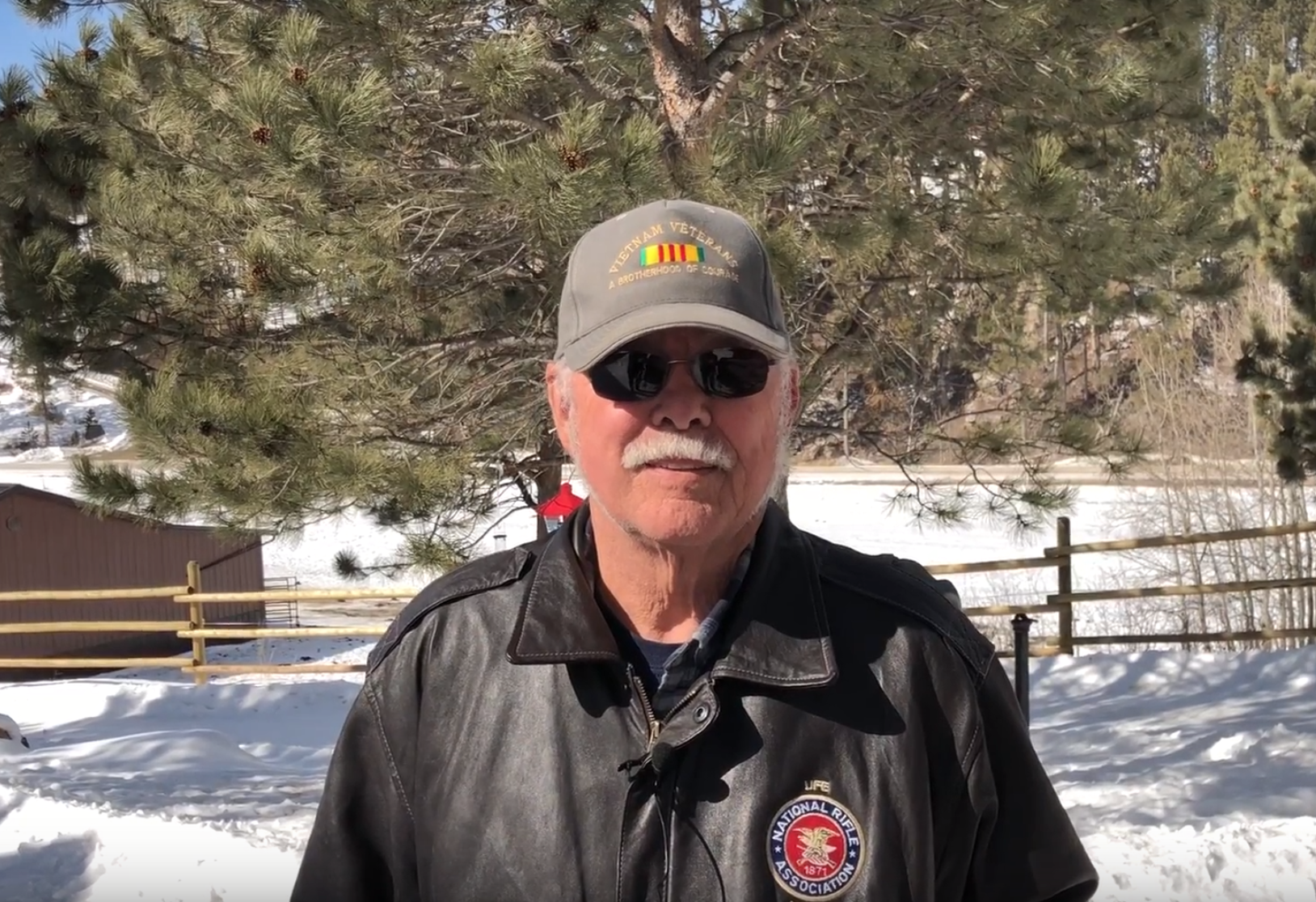

Hopkins is a 72-year-old retired Army major who served in Quang Tri during the Vietnam War and survived prostate cancer after being exposed to Agent Orange.

Hopkins, an Ohio native, said he has lived all over the world and chose Rochford to spend his final days due to the beauty, remoteness and ability to ride his horses with ease off his property just southwest of town.

“The Hills are just full of life,” he said. “It’s an experience living here. It’s gorgeous from morning to night.”

Hopkins is aware of Rochford’s role in mining history, which includes numerous small abandoned gold mines in the Hills and hundreds of small claims staked throughout the area. On a recent drive through the exploration area, Hopkins pointed out a ramshackle wooden stamp house used by miners in the late 1800s not far from his property. But he said those were smaller operations that did not have the capacity to do as much damage as a major modern gold mine.

He regularly traverses the area of the exploratory mining, using a camera and a notebook to document what he believes may be violations of the permit issued to Mineral Mountain.

Hopkins said after six months as a budding activist – attending meetings, participating on conference calls, keeping up with documents and regulatory filings – that he and his wife are already tiring of the fight.

“My nature is to be out in the woods hunting or riding horses,” he said. “I’m not an environmentalist to speak of, but this one has me up in arms.”

Yet, he said he won’t give up until he has done all he can to protect the Black Hills and his rural lifestyle.

“They’re going to get 60 million ounces of gold … and then they’re going to take off because they’re from Canada,” Hopkins said. “They don’t care about this territory; all they want is the gold.”