A push is underway for legislation to allow creation of charter schools that would integrate Indian culture, language and history into a curriculum designed to improve academic achievement among Native American children, who have historically underperformed in South Dakota.

Charter schools are publicly funded, tuition-free schools run independently of traditional local school districts. The schools often focus on improving achievement in underperforming student populations and may place a greater focus on specific teaching methods or subjects not offered in traditional schools.

Most still report to local school boards or some other designated authorizing agent, and students typically are held to all state achievement and testing standards.

Opponents of charter schools often argue that they shift per-student funding away from existing public schools and can allow for unorthodox or untested teaching methodologies and curricula.

Charter schools are considered by supporters to be effective because they allow for innovation in teaching methods and also greater flexibility in curriculum development, staffing, scheduling and teaching styles, said Todd Ziebarth, senior vice president for state advocacy and support for the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools.

In South Dakota, backers of possible legislation to allow Native-focused charter schools say the schools could spur a breakthrough in reaching and teaching Native students who have been left behind by the traditional public school system.

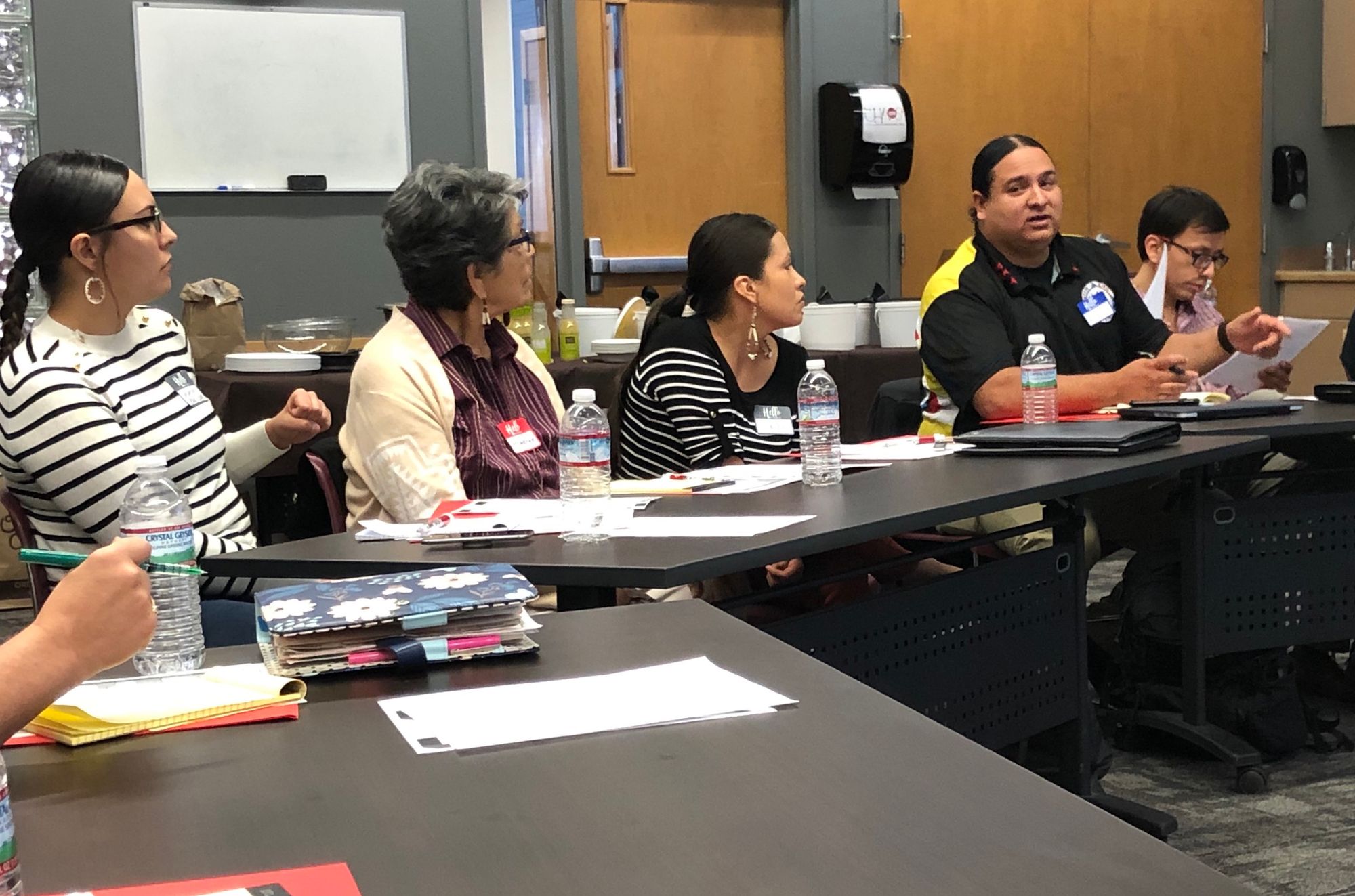

“We want to have flexibility for Indian education to be able to innovate and create, and charter schools allow for that,” said Nick Tilsen, head of the NDN Collective that is advocating for the charter-school legislation, at a meeting in Rapid City in October. “It’s a choice that doesn’t exist in South Dakota but does exist in other states.”

South Dakota is one of five U.S. states that do not permit formation of charter schools (the others are Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota and Vermont.)

Past attempts to pass legislation allowing for widespread charter schools in South Dakota have failed, and a measure allowing Native-focused charter schools only if they receive federal grants has never been utilized.

The number of charter schools has increased rapidly across the U.S. in the past three decades, with about 3.2 million students now attending 7,000 charter schools in 44 states and the District of Columbia. Collectively, they receive about $440 million in public funding.

Like public schools in America, charter schools have seen both success and failure. Two studies by the Center for Research on Education Outcomes done in 2009 and 2013 are often looked to as markers of charter-school progress. Generally, the two studies both indicated that the level of student success in American charter schools overall was no higher or lower than the nation’s traditional public schools.

However, those studies and other recent research efforts have shown that charter schools have reached higher success levels among poor and minority students.

The 2013 CREDO study, done mostly in big-city schools, showed that black students who attended charter schools gained the equivalent of 14 days of additional learning in reading and math compared with their peers at nearby public schools. The data for low-income black students showed even greater progress, with those students gaining 29 additional days of learning in reading and 36 additional days of learning in math.

Hispanic students who were learning English as their second language made even greater gains in both subjects. Meanwhile, white students in charter schools posted lower growth scores compared with their local public school peers, the study showed.

In early discussions, backers of Native-focused charter schools said that up to three charter schools could be created initially, likely on the Rosebud and Pine Ridge reservations and possibly in Rapid City.

Matt Rama, program director at Lakota Immersion Childcare in Pine Ridge, S.D., said that unless the way Native students are educated in South Dakota changes, those children will continue to suffer and fall behind non-Native children.

“Without the ability to innovate and be flexible, we’re just going to keep perpetuating the same challenges and results over and over and over again,” Rama said at the October meeting.

Tilsen said the failure of the South Dakota public education system to adequately teach Native American students makes it imperative that legislation open the door to Native-focused charter schools in South Dakota.

“It can create opportunities for our kids and use public education dollars the way they were meant to be used to help Native American children succeed,” he said.

NDN Collective has hired Ross Garelick Bell as a lobbyist and created a subgroup called the South Dakota Education Equity Coalition to push charter-school legislation in South Dakota. As of mid-November 2019, no bill related to charter schools had been filed for the 2020 legislative session.

Tough road to passage in SD

Passing charter-school legislation of any kind will be challenging in South Dakota, said state Sen. Troy Heinert, D-Mission, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe and Senate minority leader.

Opposition will likely come from those who don’t want to see per-student funding move away from traditional schools and those who may worry that charter schools could expand quickly if any at all are allowed.

“This is going to be a long process,” Heinert said. “We don’t have to be adversarial, we just have to explain why this is needed, how it’s going to work and what our expected outcomes area, and really educate the Legislature and the Department of Ed on why these schools are important.”

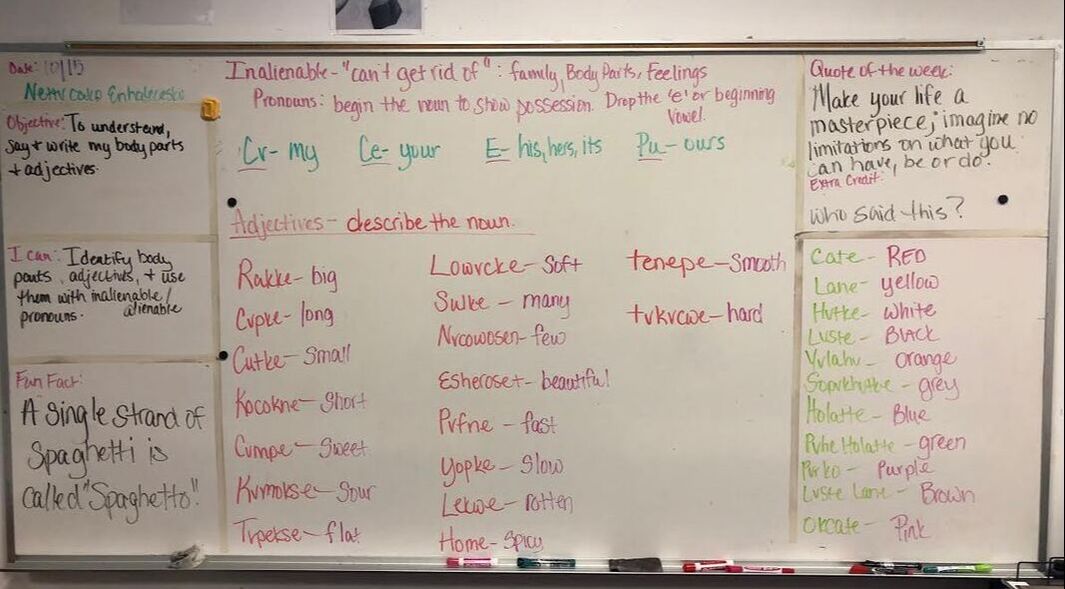

Heinert, a former teacher, said he had met several times with backers of the Native charter-school proposal and supports the schools as a way to provide more “educational sovereignty” that would allow the schools to hire more Native teachers, bring more Native language and cultural education into the classroom, and change the way student success is measured.

The legislation must be narrowly focused and allow for only a few Native-focused schools in order to have a chance of passage, Heinert said.

“My concern is that this would open it up statewide and I don’t think that would have the support through the Legislature,” he said. “We need to keep it focused on this group and what they’re trying to accomplish.”

Heinert said the bill language and arguments in support must not allow for openings in which other interest groups could seize upon the legislation to broaden it for their own purposes.

“What I don’t want to have happen is that we lose because once it gets into the legislative process that it somehow gets hijacked,” he said. “All the work and planning they’ve done, with their data and what they’re trying to do. It needs to stay specific to their goals.”

Heinert said he may agree to be the prime sponsor of the charter school legislation if asked.

Sen. Alan Solano, R-Rapid City, said the Legislature has traditionally not shown much interest in having charter schools in South Dakota.

The opposition has traditionally been rooted in the fact that charter schools would use state and local tax monies that now go to the traditional state public school system, said Solano, chair of the Senate Education Committee.

“We have to also keep the public schools going in the state,” Solano said. “That’s where you get into so much of the debate, that if it’s the money that follows the student, could they come up with additional funding to go about that?”

So far, backers of the proposal have not identified any specific funding source outside of using existing public school dollars.

Solano said any charter-school legislation would likely be so complex and controversial that it would take more than one session to get a conversation started and all the issues to be fully fleshed out.

For his part, Solano will not be involved in any debate, as he announced in October that he is retiring from the Legislature on Nov. 24 to focus more on his family and his occupation as president of the philanthropic John T. Vucurevich Foundation in Rapid City.

“This is probably an issue that would take a fairly concerted effort; it’s probably not a quick kind of thing,” Solano said. “It will be interesting to see if that gets any traction. We’ve had conversations before, but they just haven’t been able to get much traction in the Legislature.”

“The most powerful thing [in charter schools] is the ability to have autonomy by giving the decision-making power over key decisions, such as staffing and budgeting and teaching, to the people in that building because they are the closest to those kids.” -- Todd Ziebarth of the National Alliance for Public Charter Schools

Flexibility, autonomy are keys to success

Ziebarth said his organization promotes enactment of charter-school legislation at the state level and refinement of existing charter schools across the country. Ziebarth has provided advice and assistance to the NDN Collective and others pushing Native-focused charter schools in South Dakota.

To successfully propose a charter-school law, Ziebarth recommended having a firm plan for where the schools would be located, how many schools would be created, how many students they would attract, and what solid, sustainable funding mechanism could be used.

Ziebarth said charter schools tend to be controversial in almost every state where they are proposed. Frequently, it takes one or two years for charter-school legislation to pass when proposed in a state with a “politically friendly” legislative landscape, but may take several years to pass in states where lawmakers are generally opposed to charter schools.

“This is in most states a fundamentally big change, and some lawmakers will resist it just based on that,” he said.

Typical arguments against charter schools include that it is unfair to give the schools flexibility that isn’t afforded to other schools in the public system, as well as the fear that charter schools will take students and funding away from the public school system as a whole.

“Districts will fear that they are going to lose the money when the funding follows the kids,” he said.

The South Dakota proposal, which is still being formed, may have a better chance to pass, and do so quickly, since it is aimed specifically at improving education for Native students, he said. “But even with that specific focus, some people will still poke holes in it to oppose it,” Ziebarth said.

Charter schools in South Dakota could solve some problems that have stymied Native education for decades, he said.

Ziebarth said charter schools vary extensively in both approach and curricula. Some schools targeting improvement in underperforming minority populations, he said, seek to improve learning through a heavily regimented, “no excuses” approach in which students are held to strict standards of behavior and achievement.

Other charter schools aimed at minority populations use a more “culturally affirming” approach that is less regimented but that has also shown success.

“At the end of the day, a charter school is just a shell that allows for variations in what takes place inside that,” Ziebarth said. “The most powerful thing is the ability to have autonomy by giving the decision-making power over key decisions, such as staffing and budgeting and teaching, to the people in that building because they are the closest to those kids.”

For instance, South Dakota could open charter schools that are connected in curricula and technology as a way to prevent the loss of educational stability and consistency that occurs when families and their children frequently move off and on the reservation or from one school to another.

“As kids bounce back and forth between Rapid City and Pine Ridge, for example, they’d be in an educational environment that is connected and cohesive between one another,” Ziebarth said. “If the schools are connected, they can know that the child is coming back and the teachers can be ready for him or her, rather than having them come back and not have any concept of what the child has been doing academically or within the programming.”

Another example of the flexibility allowed within charter schools is that a charter school might be allowed to hire a teacher who shares the ethnicity or background of the target students, and who may have subject expertise and a strong desire to teach but may not yet be state certified, said Jonathan Santos Silva, an educator, researcher and head of the nonprofit Liber Institute, which focuses on improving minority education.

Such teachers would work on their certification as they taught and could forge significant connections to students in the charter school and potentially improve learning, Santos Silva said.

“Research shows that if students have some commonality with teachers, it can lead to progress,” said Santos Silva, who spent two years teaching at the Little Wound School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. “If students have even one teacher who shares their identity markers, who shares some commonality, it’s a huge benefit.”

Another technique that can boost learning among minority students is to tailor curriculum and teaching more closely to concepts that are unique to their population. For example, students might be taught math by doing analysis of local housing statistics or data about employment trends, rather than just crunching random numbers.

In other areas where Santos Silva has studied charter schools and minority education — including in New Mexico and Rhode Island — he has witnessed the traditional school system benefit from teaching techniques and learning breakthroughs that have taken place at charter schools.

“It’s not like we’re learning cool things and we’re going to hoard that information or keep those secrets; instead we would share what works with the district so there’s a flow of information,” he said. “If the charter school can show the efficacy of innovation or a new teaching method, they can take that and share it with the district, and then all schools will rise.”

Santos Silva said one charter school in Albuquerque, the Native American Community Academy, has consistently generated student test scores that are above those of Native students in the local school district as a whole.

He said the academy also uses non-traditional metrics, such as a stronger sense of identity among students and a more positive mental state, as measures of student achievement and school success.Through his research and experience teaching Native students, Santos Silva said he is convinced that positive, lasting change in education must originate with the people who live, work and raise their families in the area where schools are located.

“I think the people best positioned to improve outcomes at those schools are the people who are in that community and want to improve things for the long haul,” he said. “Instead of it always coming from the federal government or state government that has a new project or someone who comes in and does a one-day seminar, the change and progress should come from people who are already there.”

That concept could drive hiring and teaching at charter schools in Native communities within South Dakota, he said.

A model for success found in Florida

To find a model for success, backers of Native-focused charter schools in South Dakota could look nearly 2,000 miles south to the remote rural area of Brighton, Fla. The site at the northern edge of the Florida Everglades is home to the Pemayetv Emahakv Charter School, a school run by the Seminole Indian Tribe housing about 260 students in pre-kindergarten through eighth grade.

Much like the schools envisioned by backers of a South Dakota charter school program, PEC provides students with a consistent level of education in Native culture, language, history and ways of life.

Students at the school are taught two dialects of the Creek Indian language; they have lessons outside that include gardening and agriculture; they do beadwork, carving and cook traditional foods like fry bread for meals; they learn about and celebrate Seminole history. They participate in basketball, soccer and volleyball.

The cultural curriculum is accompanied by a rigorous academic structure to forge a strong foundation of knowledge and confidence that translates to success in and out of the classroom, said Michele Thomas, assistant to the principal.

“We’re revitalizing our language, and along with the stories and history and crafts and gardening, we’re putting all that into our school while also focusing on academics,” Thomas said. “We wanted the whole cultural track but we never wanted that sacrificed to the academic part because we know these kids are going to leave this school and go off the reservation, and we wanted them to be at grade level or above when they leave.”

The school, whose name translates roughly to “Our Way,” has a motto that declares, “Successful learners today; unconquered leaders tomorrow.”

Developing strong cultural identity and a sense of pride in themselves and their history is critically important to the Seminoles, who, like the Sioux, were subjected to oppression and wars with the U.S. government and attempts to deprive them of their language and culture. The Seminoles, also like the Sioux, are slowly seeing their language and culture fade away as the majority culture becomes increasingly dominant in education and other facets of life.

“It’s important to know where you came from so you can know where you’re going,” Thomas said.

The school took a long road to obtaining charter status and the resulting per-student state funding. For a time, Seminole students were integrated into the local public schools and provided one day of cultural education every two weeks. But parents weren’t happy with that and moved instead to open their own school.

The school, started as an elementary in 2007 and expanded since then, is run by the tribe but reports to the Glades County School Board, and students are required to take and pass standardized tests administered by the state Department of Education, Thomas said.

In general, PEC students show strong performance on state standardized tests and score well above Florida statewide averages.

Data from the state show that on tests taken in the 2018-19 school year, 96% of PEC third graders scored at or above grade level in reading and math and 50% in science. That year, 70% of PEC sixth graders tested at or above grade-level in reading and 91% in math, and 67% were at or above grade level in Algebra 1. Florida also gives individual schools a grade of A through F based on a range of factors that include student achievement, learning gains and graduation rate. In 2019, PEC middle school received an A and the elementary school received a B, according to state reports.

PEC has two major advantages over any Native-focused charter schools that would open in South Dakota — both related to money.

Thomas said that members of the Seminole Tribe all benefit financially with regular payments from successful gambling operations run by the tribe. The payments mean that none of the students in the PEC school qualifies for free or reduced-price government lunches, a common indicator of poverty. Most reservation and Native-dominated schools in South Dakota have high rates of students who receive subsidized government meals.

The Seminole Tribe’s overall wealth also gives PEC a big boost in its ability to pay for high-quality instruction. Thomas said the tribe provides about two-thirds of the funding for PEC, boosting overall revenues far beyond what the school receives in per-student funding from the state.

As a result, Thomas said the school has a highly qualified teaching staff of 116 teachers and employees, and the school averages only 12 students per class, according to its website.

In 2019, PEC fourth-grade math teacher Joy Prescott was named the Florida Department of Education Teacher of the Year.

In an essay regarding her award, Prescott noted that she strives every day to teach students elements of their culture while stressing relevant lessons that will be useful to them outside the school and do so in a setting where they feel comfortable being themselves.

“My job as their teacher is to provide opportunities that will help my students see their heritage as something that holds value, while at the same time fostering lessons that will help them grow academically, socially, and emotionally,” Prescott wrote. “In order to do this, I needed to build a classroom that felt safe and trusting — a space where students felt seen, valued, cared for, and respected.”