Colleges and universities across South Dakota were facing long-range financial, logistical and access challenges even before the COVID-19 pandemic struck.

Enrollment was falling, state financial support for public universities was dropping, and rising tuition led to high loan burdens for many students and reduced access to obtaining a degree for some low-income and minority families.

Beyond creating immediate health concerns on campuses, the pandemic has exacerbated those troubling trends, and has put higher education in America and South Dakota at a crossroads — presaging a time when fundamental decisions must be made about how higher education is delivered and consumed, how it is paid for and who is able to attend.

On the health front, university and college leaders across South Dakota are declaring the fall 2020 semester a victory, as in-person classes were held and relatively few students, faculty or staff became infected with the coronavirus.

But the pandemic caused upheaval in other ways, revealing three major trends that underscore the ongoing challenges faced by higher education institutions both public and private, large and small, across the state and nation: a significant shift to online rather than in-person, on-campus learning; reduced access to higher education by low-income and minority students; and revenue reductions that could reduce the quality of higher education and the value of a college degree.

Many of the same headwinds facing higher education in South Dakota are buffeting colleges across the country. A recent analysis by The Hechinger Report of nearly 3,000 colleges found that even before the pandemic, more than 500 institutions faced dire economic forecasts, that state support had declined at 700 public universities over the past eight years and that nearly half of the schools had seen enrollment drops since 2009. Some colleges have closed; others have eliminated sporting, academic or extracurricular programming.

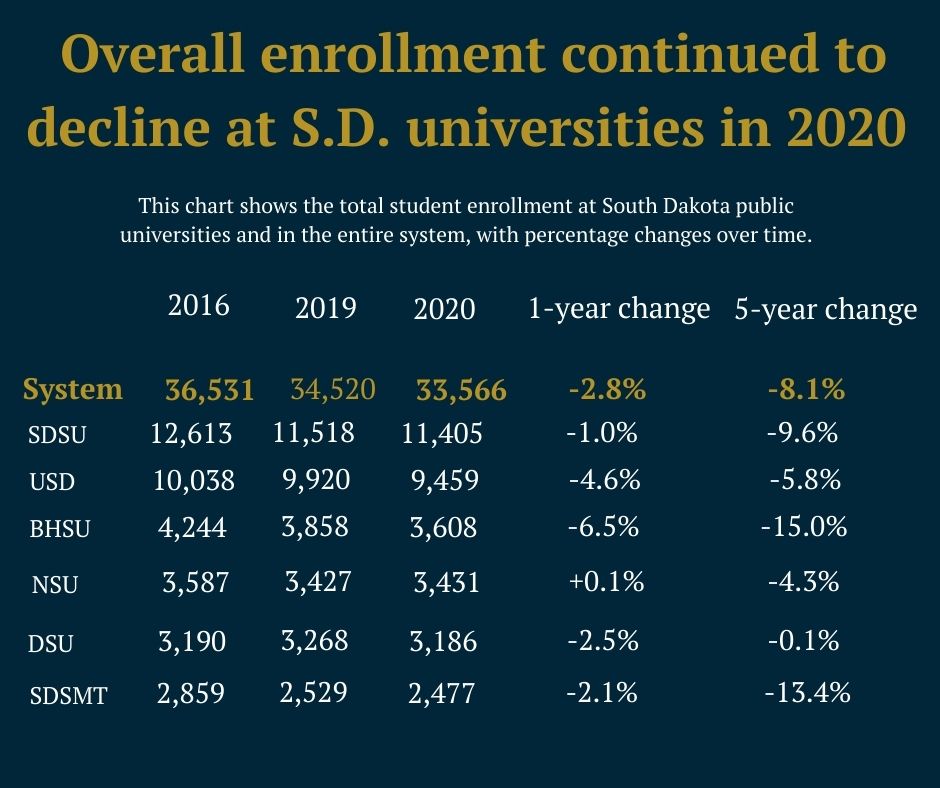

Overall enrollment in the South Dakota public university system in fall 2020 dropped by 2.84%, and private colleges reported similar declines, including a 7% drop at Augustana University in Sioux Falls. Administrators were generally pleased that the 2020 declines weren’t greater, although resulting revenue losses, still to be calculated, are certain to be in the tens of millions of dollars.

As a much-needed holiday break approaches for students, faculty and staff, followed by a spring semester still tinged with danger from the deadly COVID-19 pandemic, South Dakota News Watch interviewed more than a dozen key stakeholders in South Dakota higher education to assess how the pandemic affected teaching and learning, how it may alter higher education in the short-term and whether this unprecedented time may lead to fundamental, long-term changes in higher education.

“We’re just preparing to see what this new world looks like to us now, and some pieces of that equation we’re not ready to fill in just yet,” said Brian Maher, executive director of the South Dakota Board of Regents. “This is the beginning of the puzzle of what the pandemic will do to us, not only from an instructional-delivery standpoint, but [also] a students-on-campus standpoint, and ultimately from a revenue standpoint.”

The costly shift to online learning

Colleges and universities saw a great migration of students to online education during the pandemic, which could be seen as a coronavirus safety maneuver and a temporary shift, but which state data shows is a continuation of a larger trend.

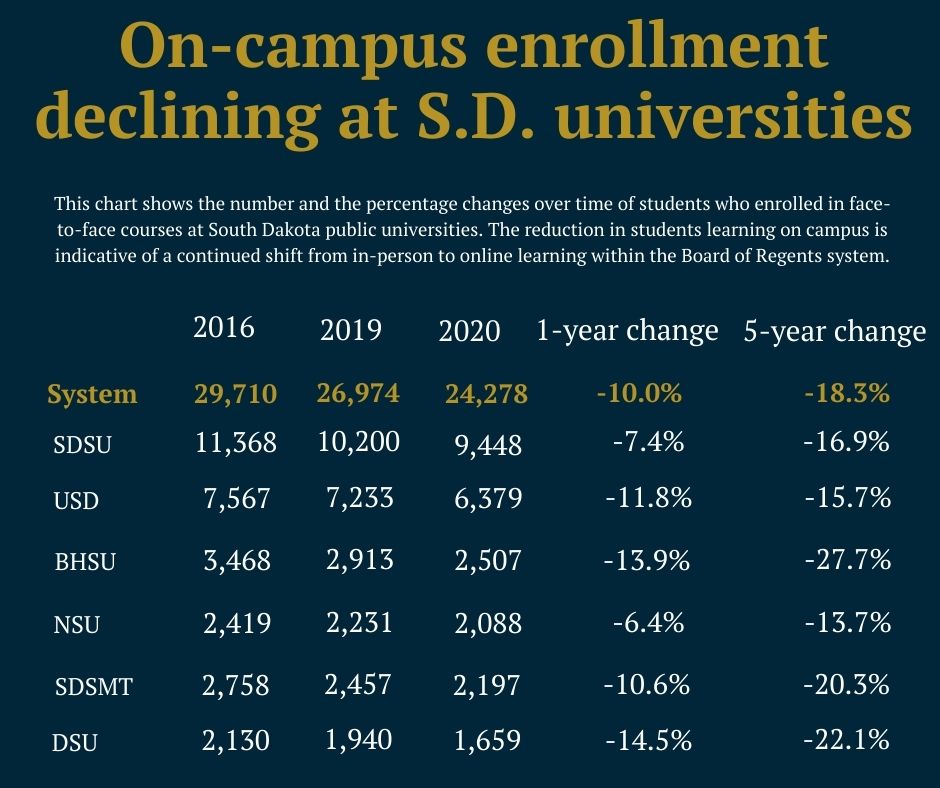

Board of Regents data show a 10% drop in face-to-face learning in the regental system from fall 2019 to fall 2020. But from 2016 to 2020, face-to-face enrollment fell by about 18.3%, or 5,500 students, from 29,710 to 24,278.

Regental data also show a sharp rise in students who enrolled in an online course in the past year and over the past five years. The system saw 27,504 students enrolled in a distance-learning course in fall 2020, a 59% jump over fall 2019 and a 66% rise since fall 2016.

The Regents created an online option in 2000 when they initiated the “Electronic University Consortium” that sought to offer statewide distance learning aimed at providing new opportunities for “place-bound, adult and otherwise non-traditional learners.”

But now, online learning has grown into a viable option for all students, including traditional incoming freshmen who choose to live at home and for on-campus students who take online courses in addition to in-person classes.

Just as a decline in overall enrollment reduces college revenues, the shift to online learning carries its own revenue challenges. Students who do not live on campus cost universities about 40% of the revenue obtained from students who live, eat and park on campus. At the University of South Dakota, which saw its overall enrollment drop by 5.8% from 2016 to 2020, the university saw face-to-face enrollment drop by 15.7% over that time frame.

At USD, a full-time on-campus student pays about $18,560 in tuition, fees, room and board, while an online student does not pay the roughly $8,000 for housing and a meal plan. In South Dakota, per-credit tuition for online courses is about $85 higher than for in-person courses, but the higher rate — even at 30 credits a year and $2,500 more in annual tuition — does not nearly make up for the lost housing and meal revenues, resulting in a potential $25 million revenue reduction systemwide per year.

Black Hills State University in Spearfish, a liberal arts and teacher’s college, saw overall enrollment fall by 15.0% in the past five years (4,244 to 3,608), but had the greatest shift away from face-to-face learning in the system, losing 27.7% of its face-to-face enrollment over that time (3,468 to 2,507).

Providing options for an increasing number of students who want to learn online while meeting the need for consistent revenues is likely to be more difficult over time, said BHSU President Laurie Nichols.

“The competition coming to us online is pretty fierce right now and there are many, many students that are opting to do more of their education online,” Nichols said. It’s a balancing act and it’s probably one of the greatest challenges we have in higher education leadership today … figuring out how do we balance those two somewhat competing forces.”

Maher said the loss of “auxiliary” revenues from housing, meals and event attendance could create a significant drain on the university system if the trend toward online learning continues as expected after the pandemic subsides. Businesses in cities where universities are located will also see lost business if the online shift continues or picks up pace.

“What does it mean to us if enrollment continues to go down or if our students aren’t learning on campus?” Maher said. “What does it mean to us in terms of lost revenue from a housing perspective, from a meal-plan perspective, from an attendance at athletic events perspective? There are a lot of pieces that go into that auxiliary budget that are still unknown, and we don’t know the impact of those losses yet.”

Instructors and students say that teaching and learning by computer over the internet added another stressor during the pandemic, especially for professors who were not familiar with teaching remotely and students unfamiliar with online learning.

Almost all colleges and universities in South Dakota took steps to provide safe in-person learning by requiring or urging use of masks, creating additional space for social distancing and reducing class sizes through hybrid courses.

Research into the effectiveness of online learning remains unsettled, though some students and instructors question whether something critical is lost by not holding classes in person.

“It’s no secret students don’t learn as well online,” Augustana student Jenifer Fjelstad, a 20-year-old junior journalism and French major, wrote to News Watch in an email. “Online learning feels like going through the motions to get an assignment done or get a certain grade, but in-person learning lets me lean into my natural interest about the subject and really learn.”

Dakota State University professor Mark Geary, president of the statewide faculty union, had experience with teaching online before the pandemic and said he had success doing so during the fall.

But Geary acknowledged that online teaching is “a complicated process to do it well and keep everyone engaged.”

Geary said some students would get distracted by roommates playing loud music or playing video games that ate up bandwidth and reduced connectivity. Geary and others also lament that online learning reduces the personal connection between teacher and student that can lead to educational breakthroughs.

“It’s really challenging to build your student relationships in your online classes,” he said.

Geary said he was able to use online teaching platforms that encouraged creativity, such as an assignment that prompted students to create a theoretical habitat on the planet Mars.

He noted that given the uncertainty of the pandemic, the rapid shift to online teaching and the fact that some students were in quarantine at times, he shifted his grading standards down somewhat.

Some administrators and students said online learning eliminates critical elements of the traditional on-campus experience, such as learning to live and work with others, including peers from diverse backgrounds, and networking opportunities and relationship-building that can aid in career advancement later.

Shifting too far toward online learning could also lessen the value of some degrees, particularly those that require students to have hands-on, experiential learning, said Barry Dunn, president of South Dakota State University.

Dunn said he believes the use of technology will continue to expand in college courses but will never supersede the value of in-person, on-campus teaching in many subject areas.

“You want your nurse to have gone through a nursing program with hands-on clinical experiences, right? That’s just fundamental,” Dunn said. “I’d personally rather have somebody designing a bridge who had worked in face-to-face courses.”

“You want your nurse to have gone through a nursing program with hands-on clinical experiences, right? I’d personally rather have somebody designing a bridge who had worked in face-to-face courses.” – Barry Dunn, president of South Dakota State University

Despite steady decreases in face-to-face learning, several administrators said the pandemic may actually heighten interest among students who want to live and learn on campus and could reverse the online trend somewhat. They also think that the experience with teaching remotely to stay safe during the pandemic will lead to more use of technology that enhances rather than replaces in-person learning.

Ben Iverson, enrollment director at Augustana University, said the school surveyed students over the summer and found they “resoundingly” preferred the on-campus learning experience.

“So that will continue to be the core of what we do here at Augustana,” Iverson said, “even if at times we integrate or blend technology into the teaching experience.”

South Dakota Mines engineering student Andrew Ward, 20, said he found hybrid courses to be the most effective, but added that he benefited from online lessons that allowed him to go back and review tapes of lectures on concepts he didn’t fully understand the first time around.

Revenue concerns rise due to pandemic

The COVID-19 pandemic is certain to create more financial stress on a public university system in South Dakota that was already facing significant revenue challenges.

Systemwide total student enrollment, a key driver of college revenues, fell by 8.1% from fall 2016 to fall 2020, from 36,531 to 33,566. Administrators point out that some recent dips were in enrollment of international students, who they hope will return once the pandemic and travel restrictions subside.

While revenue losses from the fall semester haven’t been tallied, the six schools in the state university system already lost $16 million in the spring in reimbursements made to students for tuition, fees, housing, meals and parking after shifting to remote learning. Some losses were offset from pandemic aid provided by the federal CARES Act that supplied $14 billion to U.S. colleges and universities.

Tuition, fees and room and board revenues made up about 38% of the total system budget of $832 million in 2020. Meanwhile, state financial support for education has been on the decline for several decades. While the state provided about two-thirds of the cost of public higher education in the 1960s, state support has fallen to about 34% today, and the financial burden on students has risen correspondingly.

The pandemic hit South Dakota public universities at a time when they were already under scrutiny by a legislative panel that will spend more than a year examining system operations.

The Senate Bill 55 Task Force is holding meetings around the state to seek efficiencies in spending and operations, said state Sen. Ryan Maher, R-Isabel, who led efforts to create the task force.

“We’re putting a substantial amount of money into the system, and the question is, Are we getting the most efficiencies we can out of the system?” Sen. Maher said. “Hopefully we can correct the ship and the trajectory we’re on.”

Sen. Maher said early meetings have uncovered potential savings such as consolidation of food-service provision through a single contact rather than individual contracts with different providers at each university, or centralizing some educational programs he said are redundant. He is also concerned that universities continue to build new structures and repair old ones at a time that more teaching is moving online.

For example, Sen. Maher shared a task force report indicating that SDSU had spent about $295 million on major capital projects since 2010 — including the $65 million Avera Science Center and $95 million on an athletic complex and a new football stadium — and has another $42 million in projects projected for completion soon.

Private colleges in South Dakota, which tend to have significantly higher tuition than public universities, are also making major capital investments. Mount Marty University in Yankton, where undergraduate attendance costs $37,500 a year, recently built a $15 million field house and a $4.5 million dormitory; Augustana University, where undergraduate attendance costs about $45,000, has announced plans for a $110 million residence hall addition and upgrade project.

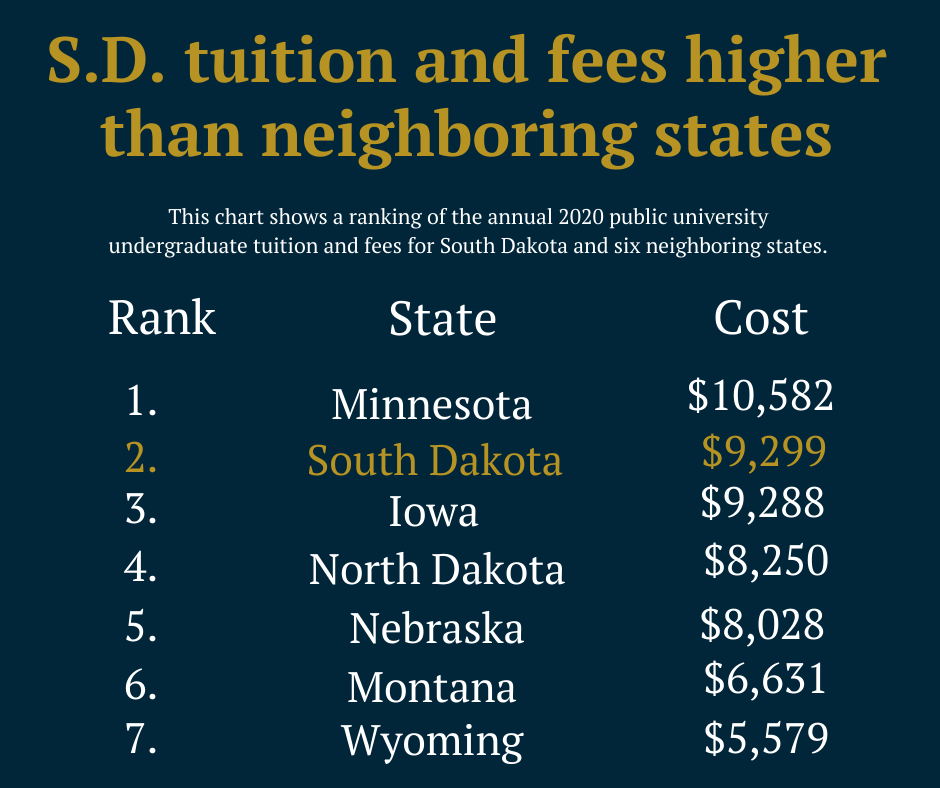

The state charges public university students a fee that pays for some of the new construction occurring on campuses, and Sen. Maher worries that continued spending on buildings will lead to tuition-and-fees increases that may price some families out of sending their children to public universities.

“How are they going to make those bond payments? That’s a big question; where is that money going to come from?” Sen. Maher said. “The cost of a four-year degree in South Dakota is expensive, and we want to hold off on any more tuition increases.”

SDSU President Dunn acknowledged that it will be a challenge moving forward to maintain campus infrastructure at a time when enrollment is falling or shifting online.

“Tremendous infrastructure was built up over a century in a model that predated the web, and so just the maintenance and repair, let alone making new modern facilities, is at odds with an online world,” Dunn said.

Two former higher education administrators in South Dakota — former Regents president Harvey Jewett and former USD president Jim Abbott — argue that greater state investment is critical to maintaining the high-quality education the state system has provided despite ongoing state cuts.

In a 55-page public letter sent to Gov. Kristi Noem, the Legislature and the Regents, the men called 2010 to 2020 a “lost decade” in regard to education funding. They said that $250 million in funding to the university system has resulted from state cuts and spending reductions by the Regents, and that those reductions have put the quality of the system and the value of degrees it awards at a breaking point.

In an interview with News Watch, Jewett said the system has done an excellent job at attracting in-state and out-of-state students and hiring qualified instructors as the cuts continued. But he said that without greater state investment, and perhaps a small tuition increase, the university system will begin to falter.

“There will be collapse — you can’t go on this way forever,” Jewett said. “The quality of the education will fall and the reputation of your schools will fall.”

Given the formation of the task force and past actions of the Legislature, it seems unlikely state funding for higher education will rise dramatically any time soon.

University of South Dakota President Sheila Gestring said she welcomes the review by the Senate task force because it will point out how efficiently state universities are already operating. She said USD spends only two-thirds of the money spent by like-sized universities across the country to produce a graduate.

Gestring said she and other administrators are always on the hunt for new ways to save money while still providing a high-quality education at an affordable cost for students, but that a tipping point in quality might be reached eventually.

“My concern is that even with all those efficiencies that we’ve enacted, we’re running out of ways to address the bottom line through efficiencies,” Gestring said. “I just don’t know that we can do much more there, and the costs don’t go down.”

Public university tuition in South Dakota is the second-highest among public systems seven Great Plains states, trailing only Minnesota. At $9,299 for resident undergraduate tuition and fees, South Dakota is higher than Wyoming, Montana, Nebraska, North Dakota and Iowa. The average student-debt load for 2019 university graduates in South Dakota was $25,427.

Maher said the increasing cost of obtaining a college degree in South Dakota may push more students to attend out-of-state schools or move into the technical college system. The state has seen a decline in the number of South Dakota high school graduates who have enrolled in the university system, from 3,207 (36%) of graduates staying in the state in 2010-11 to 2,910 (32%) staying in 2017-18.

Competition for new enrollees remains high in South Dakota among both public and private schools. The private Dakota Wesleyan University in Mitchell, for example, announced this fall that it would begin offering a $2,000 payment and scholarship offers to students who transfer to the college from elsewhere after Jan. 1, 2021.

The shift to two-year tech schools is already occurring. The pandemic has highlighted the continuing move of students into the South Dakota technical education system, which provides a cheaper, faster path to a post-secondary degree or trade certification and possibly a good job. As public and private four-year colleges saw enrollment declines in 2020, South Dakota’s four technical schools saw a slight rise in enrollment in fall 2020, coming on the heels of a 13.8% jump in enrollment over the past five years.

The annual cost to enroll in a South Dakota technical college is about $7,000 and students do not have to pay to live, eat or park on campus.

Employment and income challenges that arose amid the pandemic will only increase the value of a technical degree, said Nick Wendell, executive director of the South Dakota Board of Technical Education.

‘With spiking unemployment, the deep pandemic impacts and the ripple effect on the economy, getting a credential or a technical degree is a really good way to maintain career security and work in any community large or small in South Dakota,” Wendell said. “There’s probably a pretty high-paying, in-demand position available for you in South Dakota with a technical degree, and I think that message has resonated with a lot of folks.”

Wendell is working to incorporate the technical colleges further into the overall range of options for higher education in South Dakota, seeking ways to make technical credits more transferable to the university system. Some high school graduates and non-traditional students may seek a technical degree, earn money for a few years and then return to get a four-year degree, he said.

“A technical degree doesn’t have to be your end point,” Wendell said.

He said technical schools can provide an affordable, flexible path to a better life for the nearly 25% of South Dakota high school graduates who do not enroll in any post-secondary program within 18 months of graduating.

“Think about the impact that has on our workforce, on those young people’s ability to have any type of upward mobility or make an investment in a home,” he said. “It’s limiting for those individuals, but it’s limiting for us as a state as well.”

As the pandemic goes on, and the cost of higher education continues to rise, some parents and their children are making tough choices about how, where and when to go to college. Maher, the Regents CEO, said he is concerned that some students may decide to take a gap semester in the spring, especially if they did not enjoy or find enough value in the shift to online or hybrid course.

Parent Julie Becker of Sioux Falls, and her daughter, Sydney, had already shifted their priorities before the pandemic and did so again as it dragged on.

Sydney, 19, at one point hoped to attend USD in Vermillion, but chose to save more than $9,000 a year by living at home and attending the university center satellite campus in Sioux Falls instead. After seeing the savings, and then watching the shift to online and hybrid courses during the pandemic, Sydney has now decided to complete her accounting degree in Sioux Falls and not transfer to the campus in Vermillion after her sophomore year as planned.

Julie Becker, who runs the St. Francis House shelter in Sioux Falls, said she let Sydney make her own decisions, and supported her frugal approach after seeing her older son run up about $25,000 in student loans by moving to Minnesota to study at St. Cloud State University. Yet she and her husband, both college graduates, wonder if their daughter’s desire to avoid taking out loans is costing her an important part of the college experience.

“College isn’t just the classes, it’s the people you meet and the friendships and the study groups — all that goes with it,” Becker said. “She is missing out on the social aspects of going to college.”

Becker said she believes the university system in South Dakota will have to adapt, find new ways to deliver teaching, and change its financial formula, in order to keep higher education as an affordable option for future high school graduates.

“The pandemic brought to light all those things that were already playing out,” she said. “I think the institutions are going to struggle because you’re already seeing them losing students on campus, which is then impacting their ability to pay for infrastructure, dorms, or personnel and programs.”