Hundreds of South Dakota residents are caught in financial limbo wondering if the tens of thousands of dollars they owe on student debt — and which they were promised would be forgiven if they entered public-service careers — will actually ever be eliminated.

Those South Dakota residents include teachers, police officers, employees at charitable organizations and even members of the military who signed up to participate in the federal Public Service Loan Forgiveness program. For many, their debts have grown to unmanageable levels over their years of work in relatively low-pay positions and due to entry into income-driven repayment plans.

Created in 2007 under the George W. Bush Administration, the PSLF program began as a way to encourage college graduates to pursue public service by working in government or charitable non-profits. The PSLF was supposed to forgive a person’s remaining student loan balances after they made 120 qualifying monthly payments, a period spanning roughly 10 years. All 10 years had to be spent working in public service.

But the program’s most compelling promise has, so far, gone largely unfulfilled. The latest data from the U.S. Department of Education, which runs the program, show that just 864 of the roughly 76,000 fully processed PSLF forgiveness applications had been approved as of March 31, 2019. That is an approval rate of less than 1.1%.

According to the state Department of Education, 275 borrowers from South Dakota had submitted 347 applications for loan forgiveness under PSLF by April 25, 2019. Citing privacy concerns, the department would not release the number of applications that had been approved, denied or that were pending. But the department did note that information is not released when any data set includes fewer than 10 people.

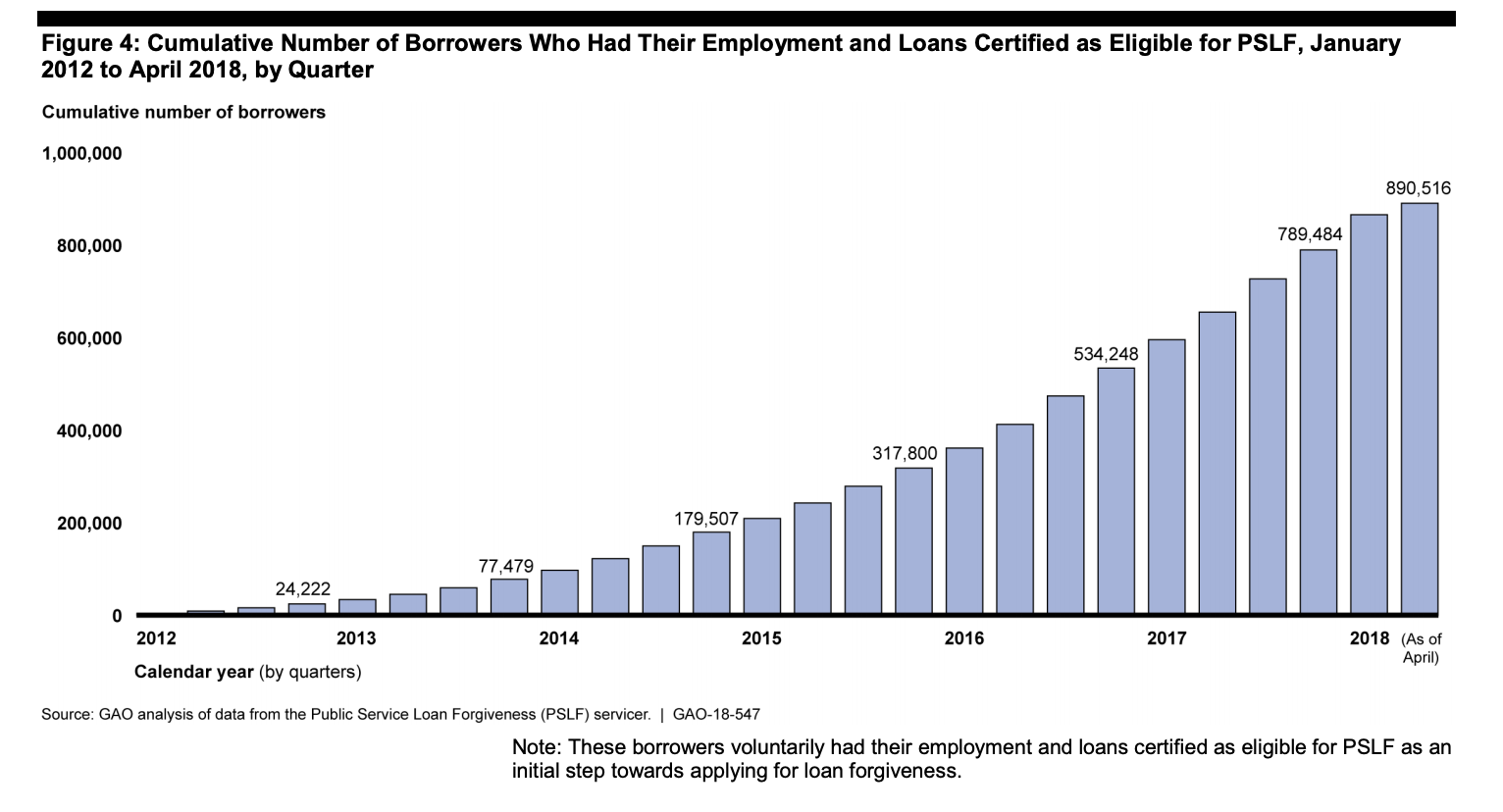

The loan forgiveness was intended to help offset lower wages typically paid to public-service employees. As of March 2019, about 2.1 million borrowers nationwide had their loans and jobs certified as eligible for PSLF. Most borrowers chose to use income-driven repayment plans that reduce monthly payments but often result in loan principals growing over time.

The failure of the PSLF program is just one element of a growing national problem in which college graduates are increasingly carrying major debt loads that inhibit home ownership, entrepreneurship and the ability to plan for a stable financial future. Nearly three-quarters of college graduates in South Dakota carry some level of college debt, with an average of more than $30,000 owed per person and well over a billion dollars owed overall. Debt levels have increased as tuition, fees and other costs have increased and, especially in South Dakota, as tuition assistance has become more difficult to obtain. Meanwhile, college debt among recent graduates has become more difficult to pay off because wages have not kept up with rising college costs.

Experts, officials and borrowers all say confusion and miscommunication are rampant with the PSLF program. A 2017 report by the Consumer Financial Protection Bureau called “Staying on Track While Giving Back,” detailed numerous problems with PSLF even before any applicants applied for forgiveness. In October of that year, when the first group of PSLF eligible borrowers started applying for loan forgiveness, more than 99 percent of the applicants were denied.

South Dakotans are among those suffering from the broken promise of the PSLF program, said Eric Olilla, executive director of the South Dakota State Employees Organization.

“I know people have been denied,” Olilla said.

Many state employees were relying on PSLF for their financial wellbeing and are worried they could be left to pay what has in many cases become much larger debts than were originally taken out, Ollila said.

Problems in PSLF have led to a lawsuit filed against the Department of Education in July 2019 on behalf of eight teachers from around the country and the American Federation of Teachers. U.S. Education Secretary Betsy DeVos has called for dismantling PSLF and included a measure to do so in the department’s 2020 budget request.

U.S. Sen. Mike Rounds, R-South Dakota, has said he supports efforts to review PSLF but stopped short of calling for its destruction.

“I believe it’s healthy to periodically review federal programs to make certain they still have merit, they’re a good use of taxpayer dollars and they are working as Congress intended,” Rounds said in an email response to questions posed by South Dakota News Watch. “The PSLF is no different, particularly given the program’s widely reported issues approving loan forgiveness applications.”

Rounds said that his office had helped at least one constituent secure loan forgiveness under PSLF in 2019 after they were wrongfully denied.

It is difficult to know how many South Dakotans are hoping to use PSLF or how many have applied and been denied loan forgiveness under the program. The Department of Education doesn’t report PSLF statistics by state.

Gov. Kristi Noem told South Dakota News Watch that her staff has requested data from the federal education department about the PSLF program and how South Dakota borrowers have been affected.

The data request is an effort to “assist in the larger conversation of higher education affordability,” Noem said in a statement.

“I want state employees to know that my administration is one that empowers families and takes care of its people,” Noem said.

Still, South Dakota public employees such as Jerica Slocum, who now owes the federal government $20,000 more than she originally borrowed, are worried that they’ll be stuck paying back a debt they would not have owed if not for the promise of PSLF.

“At first I really had faith in this program, but now I feel like criminal activity has been committed against me,” Slocum said.

Twice the debt and one way out

Slocum, 36, of Isabel, is using an income-driven repayment plan to make loan payments and is hoping her debt will be forgiven under the PSLF program. She graduated from Minnesota State University at Mankato in 2010 with a teaching degree and went to work in the Eagle Butte School District as a social studies teacher.

In 2013, Slocum discovered that she was eligible to participate in the PSLF program. The program seemed almost too good to be true, but she got her job certified as eligible for PSLF and consolidated her loans anyway.

“I probably would have been paying for the rest of my life. This program was kind of my saving grace,” Slocum said.

Partially because South Dakota’s teachers are among the lowest paid in the nation, there were a few years that Slocum didn’t make enough money to be required to make any payments at all. Fedloan Servicing, which handles all PSLF approved loans, assured Slocum those zero-dollar payments counted as qualifying payments under PSLF. But none of Slocum’s loan payments, so far, have counted toward her original balance.

Slocum borrowed about $62,000 to get her teaching degree. She admits that graduating from college took a little longer than it should have, about six years including time off to work and make money along the way. Slocum also studied abroad in Mexico and Australia. Neither program was cheap, she said, but they did make her a better teacher.

Almost 10 years after graduating and making income-based loan payments since 2011, Slocum now owes more than $84,000.

Income-based repayment plans reduce a borrower’s monthly payments based on how much money they are making, and after 20 years of payments the remaining loan balance can be wiped clean. But borrowers often see their principal loan amounts remain or even rise during that time, and then must pay income taxes on any debt that is eventually forgiven.

According to the 2017 consumer protection bureau report, the Department of Education estimates that because a typical borrower’s monthly payments increase as their income increases, they will usually end up paying more than they borrowed before seeing their loan forgiven or paid off. But public employees don’t typically see their incomes rise as fast as their private sector counterparts. Without PSLF, public employees would end up paying far more of their lifetime earnings toward interest on their student loans than private sector employees, the report said.

Slocum said she feels stuck in her current job and financial situation. Her loan servicer has told her on multiple occasions that taking a new job, even one that also is eligible for PSLF, could derail her chances at forgiveness because it would further complicate the paperwork and the payment tracking process.

Slocum could leave teaching, take a private sector job and stay in an income-driven repayment plan, which is supposed to lead to loan forgiveness after 20 years of payments. But if her loan is forgiven after those 20 years, she’d be taxed on the amount forgiven as if it were income. She’d also be making a $280 payment each month for 20 years. Provided her family income doesn’t change, Slocum would pay an additional $67,200 on her loans over that period of time.

“I don’t know how I’m going to climb out of this mess,” Slocum said.

Paying the loan back isn’t what has Slocum angry, she knew that was part of the deal. What is galling to her, Slocum said, is that the federal government made a promise and, so far, hasn’t followed through on it. In the process, she’s seen what she owes more than double, a situation she wouldn’t have allowed to happen if not for PSLF.

“I would have planned things differently, if I had not been accepted into the program and given that hope,” Slocum said.

Sketchy guidelines for lenders, borrowers

Slocum has good reason to be worried. According to a September 2018 report on PSLF from the federal Government Accountability Office, the Department of Education never published a comprehensive guide for the nine federal loan service contractors to follow when borrowers asked about PSLF. As a consequence, loan servicers often dispensed incomplete information or even misinformation.

Some borrowers weren’t told about all their paperwork requirements. Other borrowers were enrolled into the wrong type of payment plan. Some weren’t told that consolidating their loans would restart the clock on the 10-year, 120-payment cycle of required payments.

One former soldier named John Scott, whose complaint was quoted in the 2017 consumer protection bureau report, said, “I was told that none of my active military service, including deployments to Afghanistan, would count for PSLF purposes.” Scott added that, “My military service, in which my leg function was sacrificed, did not count for anything [toward PSLF]. This is contrary to the alleged policy for which the PSLF program was created and it is insulting.”

Scott should have been able to make PSLF qualifying payments while serving, according to the CFPB report.

To be eligible for PSLF, student borrowers must have taken loans directly from the federal government. In 2007, when the program was created, borrowers were allowed to consolidate Federal Family Education Loans — a subsidized private loan guaranteed by the federal government — into federal direct loans. Now, most student loans are taken directly from the federal government. No new federal family loans have been made since 2010.

Several types of payment plans could be used under PSLF, including the income-based, income-contingent and so-called “Pay As You Earn” plans. Several other types of payment plans, such as the graduated and extended term plans, can’t be used for PSLF.

The 2018 GAO report noted that because there wasn’t a comprehensive guide to follow, customer service representatives routinely dispensed bad information to borrowers.

Staying current with PSLF program changes and progress was difficult for borrowers, too. They are required to file multiple sets of paperwork annually. If one piece of information was missing on one set of paperwork in just one year, the borrower’s loan forgiveness timeline could be thrown off. And unless the borrower was paying attention, they wouldn’t catch the error until applying for forgiveness. Adding to the paperwork issue was the fact that the Department of Education and loan servicers weren’t giving borrowers clear information about their loans, the 2018 GAO report said.

Reynold Nesiba, a college professor and Democratic state senator from Sioux Falls, was one of the borrowers who missed his 10-year PSLF timeline. He started borrowing for college in 1984 and stopped in 1995 after earning a Ph.D. in economics from Notre Dame University. Back then, Nesiba said, he had about $70,000 in student debt. He started working at what is now Augustana University as an economics professor in 1995 and began making payments.

“I was on an income-contingent repayment plan which allowed me to have a mortgage and get kids through elementary school and middle school, but I wasn’t paying (my loans) down,” Nesiba said.

When PSLF was created in 2007, Nesiba had been making payments for 12 years and still hadn’t made much of a dent in what he owed. Augustana University, though, happened to be a qualified employer under PSLF, so Nesiba jumped at the opportunity to use the program.

Nesiba consolidated his federal family loans into a federal direct loan, and then, based on poor guidance from his loan-servicer, enrolled in the wrong payment plan. He made almost two year’s worth of non-qualifying payments before catching the mistake. Instead of having his loans forgiven in 2018, Nesiba’s forgiveness timeline was pushed back to 2020.

Nesiba was one of the lucky borrowers. Of the more than 53,000 individuals who applied for forgiveness by the end of 2018, a total of 318 were successful, according to the Department of Education. Around 53 percent of denials were due to non-qualifying payments, meaning the borrower had made some or all of their 120 PSLF payments under the wrong payment plan and had to start over. Often, this was because the borrower’s loan-servicer gave them bad information or didn’t know which plans actually qualified for PSLF, the GAO report said.

In March 2018, Congress passed a law creating the Temporary Expanded Public Service Loan Forgiveness program. That program included $350 million to forgive loans for borrowers who had been on the wrong type of payment plan.

Early in 2019, Nesiba applied for forgiveness under TEPSLF and was approved to have more than $60,000 in outstanding balances forgiven. He joined 442 people nationwide who had been approved for forgiveness under TEPSLF as of March 31, 2019, according to the Department of Education.

“I’d been paying for 23 years before my loans were forgiven and it’s just made a huge difference in my life,” Nesiba said.

Still, PSLF forgiveness approval rates haven’t improved much. About 1% of individuals seeking loan forgiveness under either PSLF or TEPSLF had been successful by March 31, 2019.

South Dakota News Watch has filed a request with the Department of Education under the Freedom of Information Act for the number of South Dakota residents who have had their employment certified for PSLF, how many enrollees had been approved for forgiveness and how many had been denied forgiveness. The department had not fulfilled the request by the time this story was published.