SCOTLAND, S.D. — The noisy, shuddering train cars loaded with ethanol that regularly rumbled across his farm land always worried Mike Neth. He knew the railroad tracks were old and worn, and he feared a train might derail.

“If I’m out there mending fences or what have you, I get away when the trains go by because they just seem to wobble along,” said Neth, who farms the Bon Homme County land with his son, Justin.

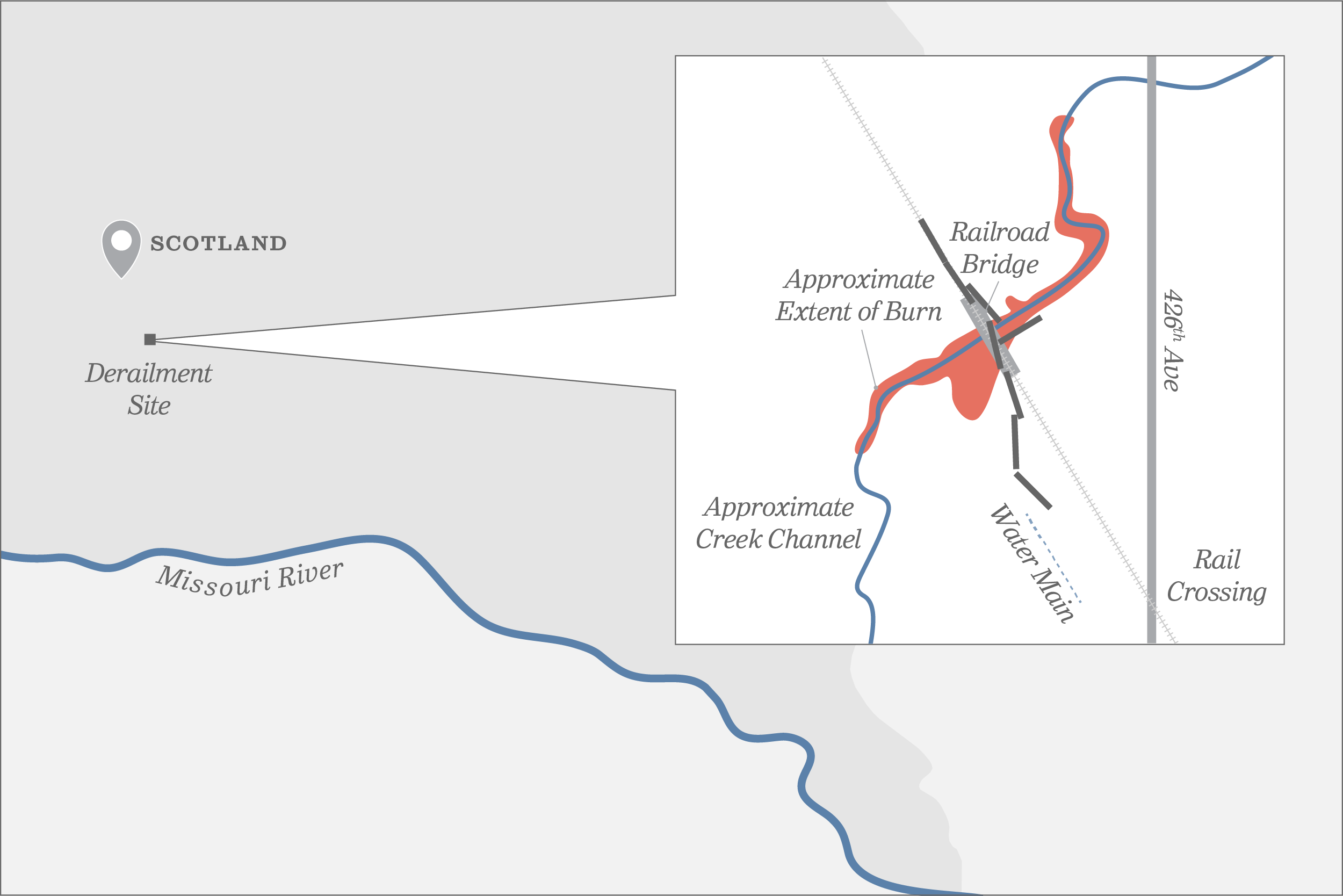

Seven tanker cars flipped off the rails, and two breached at impact. Nearly 50,000 gallons of ethanol leaked onto the ground and into the bed of Prairie Creek, where it ignited in a wall of flame. No one was injured, but the accident caused $1.1 million in damage.

“It looked like a disaster area, like someone had blown up a town,” Neth recalled. “If it would have happened in a town like Yankton, it would have been a lot worse.”

The accident was reviewed by two federal agencies, the National Transportation Safety Board and the Federal Railroad Administration. The findings raise serious questions about the safety of South Dakota’s aging railroad lines and the hazardous cargo they transport.

A subsequent investigation by South Dakota News Watch shows:

- Many railroad lines in South Dakota contain rails and other components that are at least 100 years old. They were not built to carry heavy modern tankers loaded with flammable materials like ethanol. The steel rail on the BNSF line where the Scotland accident occurred was manufactured in 1908 and installed in 1929.

- BNSF was aware of safety issues with the track prior to the accident but was within the law by not fixing them. When flaws were found, BNSF deferred needed maintenance by simply downgrading the safety classification and repair requirements of its tracks, which is allowed under federal regulations. As a result, BNSF legally kept running ethanol cars on the worn tracks.

- Producers that ship by rail in South Dakota continue to use an outdated type of tanker car to haul hazardous materials like ethanol. The older tankers are more prone to puncture and leakage than a new design of car now available and recommended by the NTSB and the Association of American Railroads trade group.

Both federal investigations cited the broken rail as the primary cause of the 2015 accident. The conclusions come as the production and transportation of ethanol by rail has grown in South Dakota and is expected to continue to increase due to federal laws requiring the increased use of biofuels.

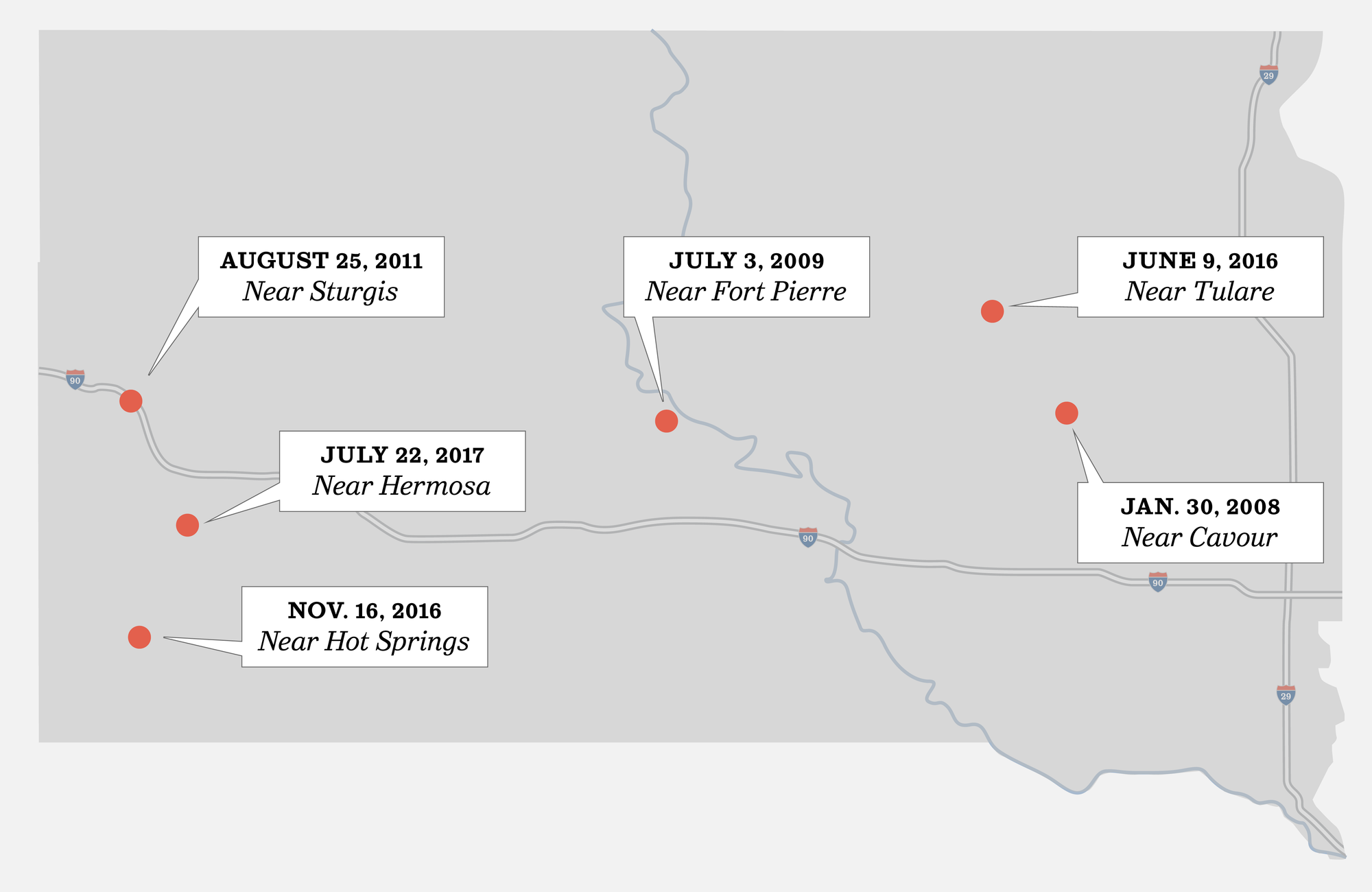

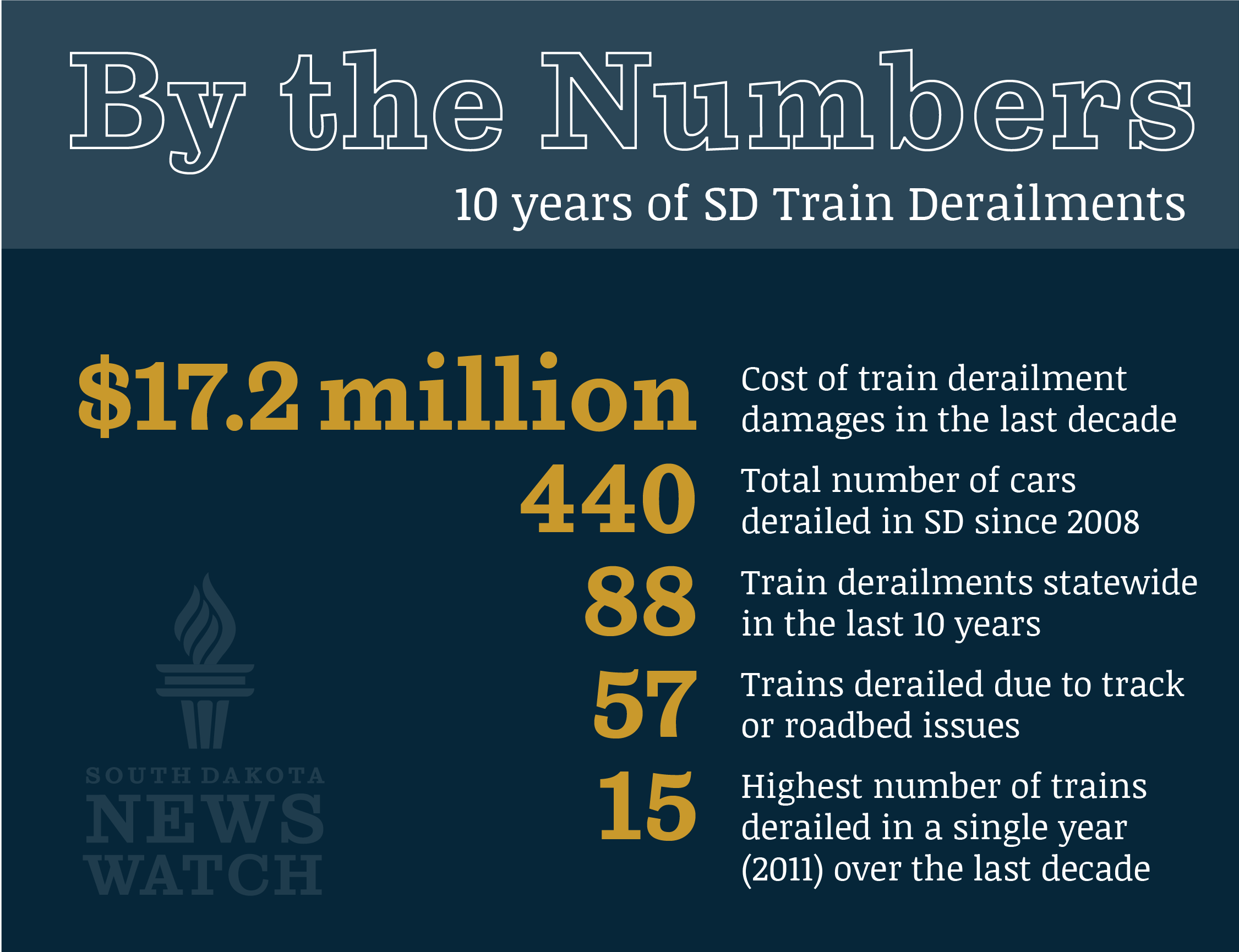

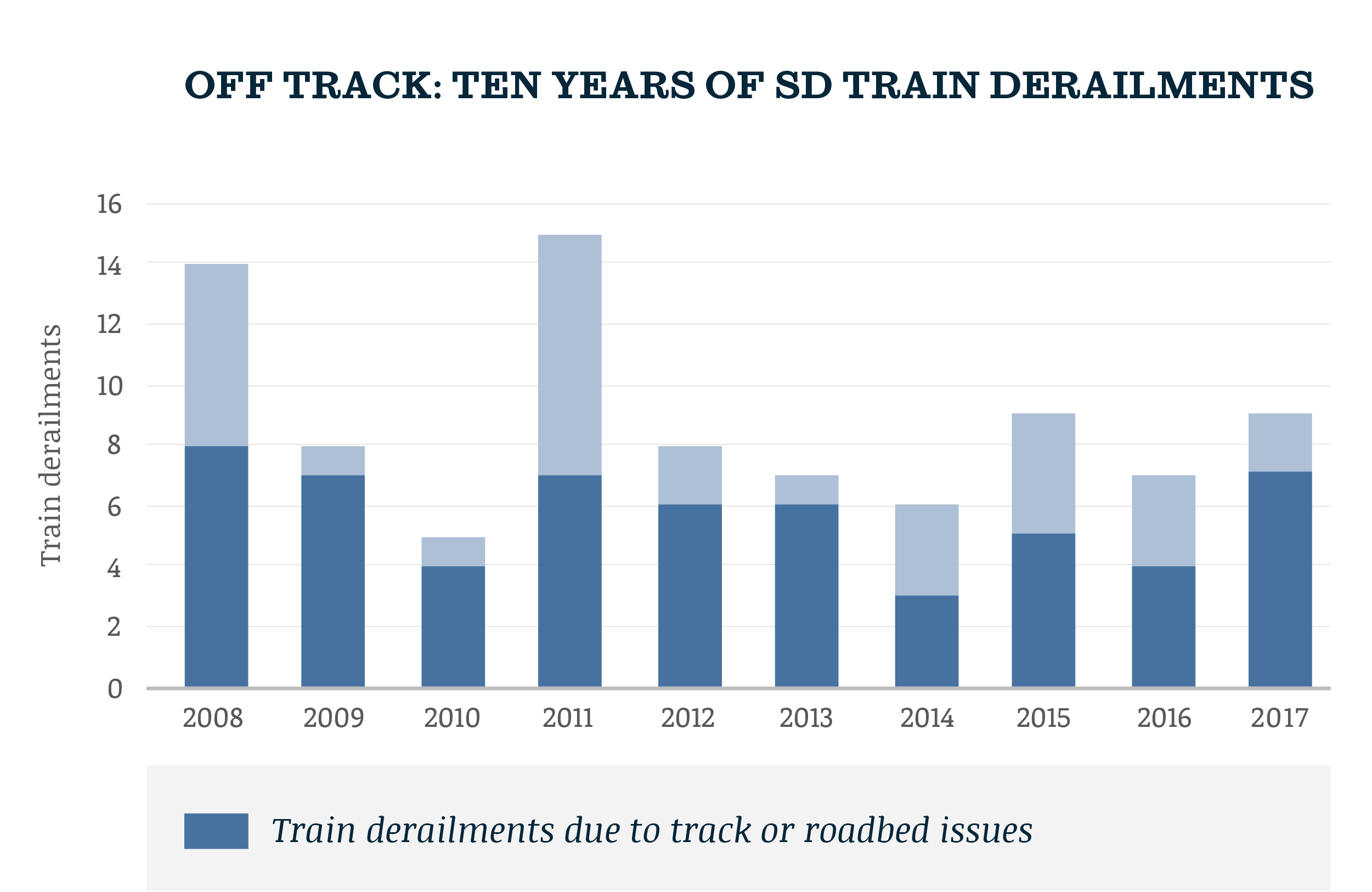

Federal data shows that problems with steel rails due to age and wear are a top cause of derailments in America. In South Dakota, 88 derailments occurred from 2008 to 2017, and 65 percent were due to rail and substructure problems, according to federal reports.

Amy McBeth, a spokeswoman for BNSF, said in e-mails that the rail company is committed to safety, noting that 99.99 percent of BNSF hazardous material shipments arrive without incident.

Since the 2015 accident, she said, BNSF has upgraded parts of the Aberdeen to Sioux City line near where the derailment took place, including installation of some new rails. The company also rerouted ethanol shipments off the section of that line, though she would not say where due to company security policies.

Self regulation is policy

The increased transport of hazardous materials on aging lines is allowed by a federal regulatory system that makes train operators responsible for maintaining and inspecting their own rail lines. By law, companies are only required to report safety findings in the case of an accident or “upon request” to the Federal Railroad Administration, one of the two regulatory agencies that oversee rail safety in America. The other agency is the Pipeline and Hazardous Materials Safety Administration. FRA does employ inspectors to oversee rail safety.

In its report on the accident, issued in June 2017, the NTSB made two safety recommendations, urging rail regulatory agencies to more closely examine routes used for hazardous materials and identify when older, more puncture-prone tankers are used on such routes.

The recommendations were rejected by the regulators as redundant of existing safety laws. They also said such measures would raise costs for railroad companies and producers.

The state of South Dakota has a limited role in overseeing the safety of rail lines in the state and has no regulatory authority over rail companies or producers.

One rail safety expert who reviewed the NTSB investigation said more accidents are likely without major safety investments by rail companies and the government, especially on rural lines like those in South Dakota that carry limited traffic.

“Because these rail lines are marginally profitable, they’re also marginally safe,” said Russell Quimby, a rail expert from Omaha, Neb., who spent 22 years as a rail safety engineer and inspector for the NTSB and now works as a rail safety consultant. “The size of rail cars has kept growing for economics or other reasons, but the track structure is always lagging behind that.”

McBeth said BNSF has spent nearly $150 million on rail improvements of various types in South Dakota over the past three years.

“We’re always working to further reduce risk on our railroad through investing in our infrastructure, following a robust track inspection program and investing in technology,” she said.

Old, weak rails

South Dakota’s railroading history generally follows the state’s population growth and economic evolution.

The first significant line was opened in 1873 after business interests in Yankton wanted to build a line to Sioux City, Iowa, to ship goods to Midwest industrial centers. After that, two sets of rail infrastructure arose — a network serving the agriculture and passenger industries in the east, and a network in the Black Hills to service the gold rush of the late 1870s. The two rail networks were connected in the first decade of the 20th century with a line that generally follows the route of Interstate 90.

Most of the lines still in use today were built during a railroad boom period lasting until about 1920. Agricultural operations began to consolidate and contract in the 1950s, around the same time that the use of passenger trains began to ebb. Those factors and the explosive growth in automobiles led to a massive downturn for rail. By 1980, 60 percent of lines in the state were abandoned.

Rail made a comeback in the 1990s with the growth of the domestic energy industry, including coal mined in Wyoming and ethanol produced in South Dakota

However, according to the state, no new rail construction has taken place since 1948, leaving old rail lines built in the early 20th century to support modern hazardous-materials tanker cars that weigh up to 286,000 pounds, a weight unimaginable at the time the rails were forged.

The age and wear of the line where the 2015 derailment took place were noted in the investigations by both oversight agencies, but the NTSB analysis is more pointed in its concern over aging rail infrastructure.

Due to age, wear and the exposure of the steel rail on the Aberdeen to Sioux City line to the elements, “the hardness of the rail at the POD (point of derailment) was about 30 percent lower than the minimum acceptable value for today’s rails,” NTSB ruled.

Federal and state documents show that many of the lines now in use in South Dakota are similar in age and safety classification to that line.

Furthermore, the old rail tracks used in South Dakota are jointed rails, short segments of steel held together by metal joints along the sides that can shift over time. Modern rails are known as “continuous welded rail,” which Quimby said are 40 percent stronger than jointed rails.

“The technology to make good steel has evolved over time, and 100 years ago it wasn’t anywhere near where it is now,” he said. “The railroad should have known better than to run trains over that crappy rail. They were monitoring it, but they should have known they were way-overloading this rail.”

FRA spokesperson Warren Flatau said even with upgraded or new rail, accidents can happen.

He pointed to the deadly derailment of an Amtrak train in Washington state in December, which appears to be speed related and happened on a new rail line. Furthermore, he said that while inspections are important, they cannot guarantee that rail infrastructure will not fail at some point.

“Broken rail is something that happens on exposed infrastructure; it doesn’t necessarily mean something wasn’t properly inspected or maintained,” Flatau said.

Old tankers less safe

The NTSB report on the 2015 accident also criticizes the continued use of older, more puncture-prone tanker cars, known as DOT-111. Studies have shown that the older cars are more prone to breech or leak in a derailment than retrofitted tankers or new cars that meet the higher DOT-117 safety standard. Those safer cars feature shields, improved valves and tank jackets designed specifically to avoid rupture of hazardous materials in a derailment.

NTSB notes about 28,000 of the older tankers are carrying ethanol across the country. The tankers are still used in South Dakota, though the number is not known. The report on the 2015 accident notes that of the seven tankers that derailed, the two that spilled ethanol were of the outdated DOT-111 design.

“Continued damages, injuries and loss of life caused by accidents involving flammable liquids in rail transportation are intolerable,” the NTSB said in its report.

McBeth noted that producers who ship by rail typically own the tanker cars, while railroad companies own some regular cars and the rail lines. She said BNSF has encouraged shippers to upgrade to the safer tanker cars by offering discounted rates for ethanol shipped in the DOT-117 cars.

In December, 2017, McBeth said, 56 percent of the ethanol shipped by BNSF was moved in the safer tanker cars, compared to only 25 percent a year earlier. BNSF, the nation’s second largest rail company, anticipates that 70 percent of ethanol carried by the company will be in the newer cars by the end of 2018, McBeth said.

South Dakota ethanol producers are working to steadily upgrade the safety of their tanker fleets, said Dana Siefkes-Lewis, an administrator for Redfield Energy. The company now meets the higher DOT-117 safety standard on about half of its fleet of 200 tankers, said Siefkes-Lewis, who is also president of the South Dakota Ethanol Producers Association.

Inspections but not repairs

BNSF had been warned by its own inspectors about potential problems with its Aberdeen to Sioux City line prior to the 2015 accident, but needed repairs were not made, the NTSB ruled.

The investigation showed that several safety issues with the BNSF line at and near where the 2015 derailment took place had been discovered.

One finding involved a narrowing of spacing of track rails that can lead to derailments and other heightened safety risks.

BNSF hired an independent contractor in 2014 and 2015 who found that same problem on the rails.

BNSF had a contractor inspect the rail for internal defects on a quarterly basis, according to NTSB. During inspections in April and July of 2015, no defects were found at the point where the derailment would take place, but several other locations nearby showed tracks that were “shelled, spalled and corrugated,” a condition that can indicate a weakened rail and may prevent an accurate measure of internal structural problems.

After the accident, NTSB reported that “investigators found many track deficiencies near the accident site,” including a broken rail head and vertically split rail head nearby and generally “excessive rail head wear.”

A photo in the report shows a rail from the accident site that is significantly worn down. Another image captured by a BNSF train the day before the accident shows the rail line well out of alignment, and an audio from that rain contains an audible “clunking” sound as it passed.

“The railroad knew what was wrong, and they did some of what they could, but the rest they let ride even though the risk was greater.” ~ Russell Quimby.

BNSF had completed the necessary inspections on the track and its results were within FRA safety guidelines, the reviewing agencies reported. However, “BNSF continued to operate high-hazard flammable unit trains on a track with significant defects,” NTSB wrote.

There are 1,851 miles of rail in South Dakota, of which the state owns 317 miles. The state’s focus is mainly on leasing those rail lines to some of the nine private rail companies that operate in South Dakota. In almost all cases, the state defers regulatory authority for rail safety to the federal government.

“The state does not have authority and does not regulate train cars,” Jack Dokken, of the South Dakota Department of Transportation rail division said. “They [rail companies] are responsible for all the maintenance and upkeep. If there’s a problem in the rail, the operator needs to fix it.”

Dokken noted that the state gives FRA inspectors access to all the lines it owns, and that if something major was reported to the state, steps would be taken to preserve public safety.

“They’re basically saying this is self-regulation,” said Quimby. “The FRA can’t do all of this, so let’s put this on the industry and fine them when things go wrong.”

"The worst thing that could happen did happen and may happen again." ~ Russell Quimby

Ethanol on South Dakota rails

Rail lines are the favored way to transport ethanol because the fuel can corrode steel pipelines and because ethanol plants tend to be widely geographically dispersed, making water transport unreasonable.

In 2014, U.S. railroads carried nearly 334,000 carloads of ethanol, up from fewer than 40,000 carloads in 2000, according to the American Railroad Association, a trade group.

Last year, South Dakota ranked sixth in ethanol production in the U.S. with roughly 1.1 billion gallons refined, according to the Renewable Fuels Association.

In 2011, producers shipped 3.6 million tons of ethanol, a number that is predicted to rise to 12.7 million tons by 2040. For comparison, state rail lines carried 2.6 million tons of crude petroleum in 2011, a figure expected to hold steady or drop slightly by 2040.

Compared to crude oil or other hazardous materials, ethanol is considered a relatively safe product to transport by rail because in a spill it burns off readily and quickly disperses into the air. However, in addition to the 49,743 gallons of ethanol spilled in the 2015 derailment, the accident also led to the release of the carcinogenic compound benzyne and its derivatives ethylbenzene, toluene and xylene.

A state official said an independent contractor hired by BNSF has cleaned up the spill site and chemicals, though a final signoff by the state has not yet taken place.

Since 1985, the state of South Dakota has documented 47 spills of various materials in rail accidents. The South Dakota Environmental Events Database shows that ethanol has been released in rail incidents on 10 occasions.

The database also contains reports on a variety of other spills in rail incidents, including the release of 30 tons of dry urea fertilizer in a derailment near Parker in April, 2013; the spill of 726 tons of coal in a derailment at Big Stone City in August, 2015; and the discharge of 3,000 gallons of rendered beef tallow in Rapid City in July, 1987, some of which flowed into Rapid Creek.

Quimby said South Dakota and other rural states that are using worn, aging rail infrastructure should anticipate that more accidents will occur without major investments.

“It’s symptomatic of marginal rural railroads, particularly those in the Midwest that serve the agriculture industry,” he said. “The worst thing that could happen did happen and may happen again.”