South Dakotans owe more than $1.5 billion to the federal government on loans they took out to finance their educations and many borrowers are finding themselves crushed under the weight of their college debt, even many years after they graduated.

About 52,000 South Dakotans have some debt from direct federal student loans, according to the U.S. Department of Education. Thousands more owe millions of dollars more on other federal student loan products and to private student loan companies. Those loans were made — often to people still in their teens — on the promise that the money would help provide them with a more stable, prosperous financial future.

But promises of higher pay, strong job satisfaction and financial stability haven’t panned out for many graduates. Nationally, wage growth has fallen far behind the increasing cost of higher education. In South Dakota, many graduates face high college costs and debt loads in a state known for low wages and limited white-collar job opportunities.

South Dakota college students routinely rank among the most indebted in America. Roughly 74 percent of South Dakota graduates carry some college debt, with an average of more than $30,000 owed. Only two other states, New Hampshire and West Virginia, saw such high rates of student debt. The national average student debt load is $32,731 at graduation. College tuition varies widely across the state and nation, but most students can expect to pay about $60,000 to graduate from a public university in South Dakota and several times that for private schools or those located in other parts of the country.

For Valerie Scott of Sioux Falls, getting student loans and completing two degree programs at Augustana University was relatively easy compared to trying to pay off the debt she still owes nearly a decade after graduating. Scott has paid about $42,000 on her student loans and owes about $35,000 more, she said.

She works in medical billing, and pays about a third of her income on college loans. She said she cannot afford to purchase a home and had to borrow money from her parents to buy a used car from her grandmother.

“I approached student loans as an 18-year-old with the mindset that I’d just work hard and pay them off and it would be fine,” said Scott, now 29. “When I boil it down to just me and the invisible people who lent me money, I don’t know that I feel taken advantage of. I went in knowing I was going to be paying for years, but I just feel tired and wish I was done.”

Scott is far from alone in feeling trapped by college debt. Research on student borrowing is beginning to show the potentially dire economic consequences of the nation’s nearly $1.6 trillion student debt load.

Studies show homeownership, which is the biggest indicator of stability for most American families, is being delayed or forgone completely at least partially due to student debt. In a 2017 report called “Echoes of Rising Tuition in Students’ Borrowing, Educational Attainment and Homeownership in Post-Recession America,” economists at the New York Federal Reserve Bank found that homeownership for American 30-year-olds dropped from 32 percent in 2007 to 21 percent in 2016. Up to 35 percent of the decline could be attributed to student debt, the report said.

A 2015 study by economists at the Philadelphia Federal Reserve Bank found student debt had caused a 14 percent nationwide reduction in the number of new small businesses with one to four employees over 10 years. The number of new businesses with up to 20 employees, the largest category of small business, saw a reduction of 6.2 percent due to student debt, the study concluded. Small businesses account for about 60 percent of new, private sector employment annually.

The debt issue vexes prospective, current and former college students with no end in sight. Skyrocketing college costs, reduced state support for higher education and the ease of getting educational loans have combined to make going into debt for higher education almost a foregone conclusion for many. Meanwhile, many South Dakota graduates are enrolled in payment plans that reduce monthly loan bills but create the potential for huge tax bills later in life.

South Dakota Treasurer Josh Haeder is hoping a new program can help slow the growth of college debt in the state. He is working on a financial literacy and college savings effort that could help some students avoid debt. The plan is in its infancy right now, but he wants to roll it out in April 2020. Financial literacy and more savings are needed to address what is a growing problem in the state, Haeder said.

“There’s a much broader conversation that needs to take place with 16-year-olds before they start looking at student loans,” Haeder said. “We’re talking about a huge issue here. This is a gigantic statewide and national issue.”

Pay now and pay later

Before taking their first federal student loan, borrowers are required to take a short, online course about the loan, which includes information about how and why it needs to be repaid. After that course, students are free to borrow as much as they can. Schools can educate their students about borrowing money but most don’t do much.

Student lenders, including the federal government, are eager to give students money because the loans tend to be profitable and there’s very little risk. For example, the Congressional Budget Office in 2017 predicted the U.S. Department of Education would bring in $110 billion in profit from interest on direct loans over the ensuing 10 years. Student borrowers also aren’t provided the same protections as other borrowers. It is much more difficult to discharge a student loan through bankruptcy than it is to discharge credit card debt, for example.

There hasn’t been much incentive for colleges and universities to spend time educating their students on debt. The ability of a college or university to tap federal loans as financial aid is directly tied to their students’ loan default rates, and South Dakotans’ default rates are low.

According to the 2018 South Dakota Board of Regents Fact Book, 12.8 percent of South Dakota college borrowers had defaulted over the previous three years. The state default rate was inflated by borrowers who went to for-profit colleges. For-profit college students defaulted at a rate of more than 23 percent. Public university students saw a default rate of 7.5 percent, while private, non-profit schools saw a 5.7 percent default rate. Schools lose the ability to tap federal loans for their students when default rates hit 40 percent or stay at 30 percent for three years.

Just because a student stays out of default doesn’t mean they’re making ends meet or paying off their loans. A growing number of student borrowers are opting to use income-based payment plans, an option that keeps them out of default but doesn’t end up paying the loan off. In part because of extended payment plans and income-based payment plans, people ages 30 to 39 now hold more student debt than any other age group and have since 2014.

Income-based repayment plans, many of which were created in 2010, work by reducing a borrower’s monthly payments based on how much money a borrower is making, but can leave them with a huge tax bill decades later.

Under the plans, loan payments are based on either 10 percent or 20 percent of the borrower’s income that is above 150% of the federal poverty line. If the borrower’s income is less than 150% of the poverty line in a given year, they don’t have to pay at all. In 2019, 150 percent of the poverty line for a single person was $18,735 and $38,625 for a family of four.

When income-based payment plans were created, federal officials knew many borrowers using the plans would never pay off their principal debt. Instead, they promised to forgive the loan after 20 or 25 years depending on the type of loan and whether enough qualifying payments were made. The amount forgiven would then be taxed at that time as if it were income.

By the end of the first three months of 2019, more than $813 billion worth of Americans’ direct federal student loans — currently the most common type of student loan — wasn’t being paid off. Less than half, roughly $384 billion, was temporarily deferred, in forbearance, held by students still in school or by students who had graduated less than six months earlier. About $430 billion belonged to former students who were using an income-based repayment plan, according to the U.S. Department of Education.

Brooke Moeller, a chiropractor in Chamberlain, is an example of how income-based repayment plans may seem like a good deal at first but can have serious financial implications later. Moeller, who owed around $200,000 on student loans in 2012, made five monthly payments of $1,500 each but then learned that of the $7,500 paid to the lender, her principal had been reduced by only $700.

“The gal on the phone basically told me that I needed to apply for an income-based repayment plan and that I would never get my student loans paid off if I wanted to have a family and a home,” Moeller said. “That was the moment that I pretty much broke down.”

"There is no way to keep the current approach and also reduce the amount of student loan debt nationally. That math is not going to add up." -- Jay Perry, vice president of academic affairs for the S.D. Board of Regents

South Dakota higher education officials don’t track the number of former students using income-based repayment plans, said Jay Perry, vice president of academic affairs for the South Dakota Board of Regents. They have no idea how many of their graduates aren’t actually paying their debt off and will be saddled with enormous tax bills if and when their loans are forgiven.

“That might be a bigger problem in South Dakota than in other states simply because it’s a low-wage state,” Perry said of the prevalence of income-based repayment in South Dakota.

Data available on the U.S. Department of Education’s student aid website show 19,800 South Dakotans who collectively owe $1.1 billion on their federal loans were enrolled in an income-driven repayment plan at the end of 2018.

In 2007, under the George W. Bush administration, the Public Service Loan Forgiveness program was created. The program was designed to encourage employment in public service fields by promising potential hires that they could get their student loans forgiven by working in government or nonprofits for 10 years and making 10 years of payments. In 2017, when the first group of public employees became eligible for forgiveness, more than 99 percent of those who applied were denied. The approval rate hasn’t improved much in almost two years.

Greater investment, lower returns

On average, college graduates can expect to make about $1 million more in income over their lifetime than non-graduates, said Perry. The extra earning potential is often called the “college premium” and it really hasn’t changed much over the last few decades.

What has changed is how much a degree costs and who is paying for it.

Until 2009, taxpayers, not students, were footing most of the bill for a degree from a public university. As recently as 2007, South Dakota’s taxpayers were covering about 55 percent of the cost of a public college education. In 2009, for the first time in state history, students themselves paid more than half, about 51 percent, of the cost of higher education. South Dakota students have been paying more than taxpayers ever since.

By 2018, South Dakota public university students were paying 56 percent of the cost of their education. In contrast, national statistics show that the parents of today’s college students likely paid for just 30 percent of their own education costs. Those who attended a public university prior to 1988, meanwhile, probably were paying for closer to 20 or 25 percent of their education, according to a 2017 report by the Center on Budget Policy and Priorities, a non-profit think tank.

State funding for higher education hasn’t kept pace with rising costs for everything from technology to compliance with federal rules and laws. In 2011, South Dakota made a 10 percent across-the-board cut to state spending, which added to the pressure that has forced public universities to raise tuition and fees almost every year for more than a decade, Perry said.

The nationwide average price of tuition at public colleges has jumped by more than 200 percent from 1988, when it was $3,360, to $10,230 in 2018, according to the College Board, a non-profit focused on college student success. As college became more expensive, more students were forced to borrow more money.

Annual undergraduate college costs across Great Plains

This chart shows the average annual cost of tuition, fees and room and board for freshmen at public colleges across seven Great Plains states. While South Dakota ranks low on this chart, state officials say the state is the most expensive in net college costs due to low levels of grants and scholarships available.

STATE TOTAL COST/YEAR

Minnesota $18,973

Iowa $18,521

Nebraska $16,918

Wyoming $16,387

South Dakota $16,251

North Dakota $15,048

Montana $14,329

*Total cost includes tuition, fees, room and board for 2019 fiscal year

A 2017 New York Federal Reserve report, “Echoes of Rising Tuition”, said a typical 30-year-old in 2015 had actually reduced their overall personal debt load compared to a typical 30-year-old in 2003.

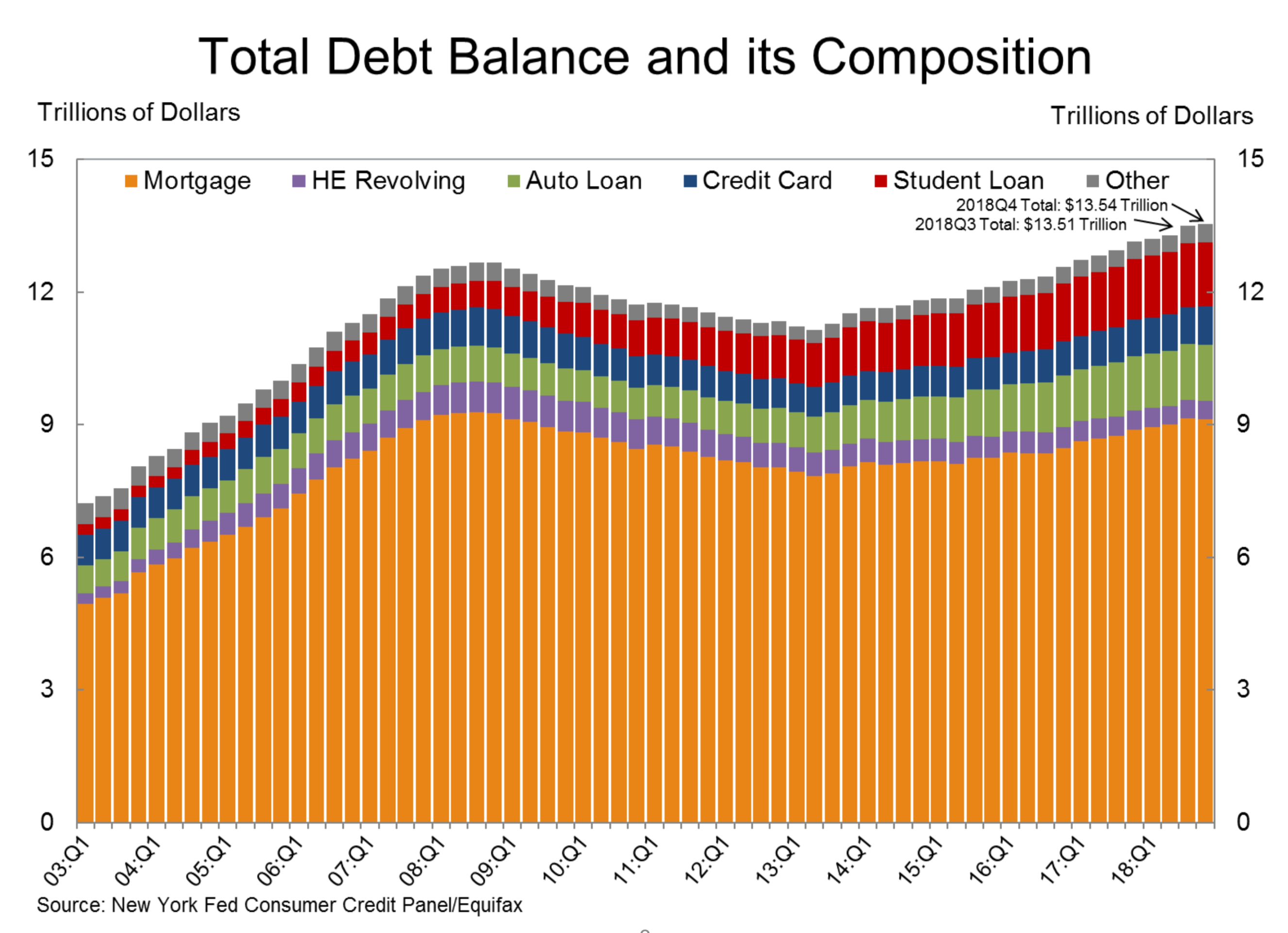

But the decline in debt has as much or more to do with increased use of student loans than any other factor. The report showed the typical 30-year-old in 2015 would have had 174 percent more student debt than a 30-year-old would have had in 2003, while at the same time carrying 36 percent less credit card debt and 28 percent less mortgage debt. Higher student loan balances make securing a mortgage, car loan or credit card more difficult.

Average wages, meanwhile, have increased far less than the price of a college degree. A July 2019 report by the Congressional Research Service found that inflation-adjusted wages for middle income Americans grew about 6.1 percent between 1979 and 2018. For top earners, wages increased 37.6 percent. In South Dakota, overall wages grew about 6.3 percent between 1979 and 2001 but growth slowed to 4.1 percent between 2001 and 2018, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce.

Graduates with heavy college debt face a daunting employment landscape when seeking work in South Dakota.

According to the U.S. Department of Labor, the state is dominated by low-wage service jobs that pay well below the national average salary. Statistics from the department in 2017 show that 71 percent of employed South Dakota residents, about 292,000 people, make under $40,000 a year. South Dakota ranks third-lowest in average annual pay statewide at under $41,000 a year, with the national average at $55,470. Meanwhile, the data show that 37% of jobs in South Dakota are in low-pay fields such as food service, administrative assistance and sales.

Meanwhile, the state ranks at or near the lowest pay in the nation in several employment categories that likely require a college degree, including architecture/engineering, education, life/physical/social sciences, arts/design/sports/media, computer and mathematical, legal fields, community and social services and business and financial operations.

Graduates who take on debt but then find an unreceptive employment marketplace can struggle to thrive or live independently.

Sara Carlson of Brookings started college at Concordia College, a private school in Moorehead, Minn., in 2008, but transferred and graduated from South Dakota State University in 2011 with a degree in graphic design. She had about $30,000 worth of debt when she graduated.

Carlson, now 30, couldn’t find a job in graphic design and currently works at the Runnings store in Brookings as a department manager making slightly more than $34,000 a year. She now pays $260 a month on college loans and has about two and a half years of payments left before her debt is paid.

“On my salary, my monthly budget comes about $200 short,” Carlson said.

The current funding model for college likely is unsustainable, said Perry, of the board of regents. Because students now shoulder most of the costs of college and because those costs continue to increase, the amount of debt they’ll have to take on will keep growing.

“There is no way to keep the current approach and also reduce the amount of student loan debt nationally. That math is not going to add up,” Perry said.

The regents have worked with South Dakota high schools to create dual-credit programs so students can earn college credits before arriving on campus, Perry said. The university system has also implemented exploratory studies programs at its campuses in an effort to help students pick a major and graduate within four years. The regents have also been lobbying aggressively for the state to create a needs-based scholarship program in an effort to bring net-costs to students down.

But Perry said none of the board’s recent efforts will affect the state’s current student debt load and the borrowers who owe money. He said a comprehensive set of reforms is needed to turn the tide of oppressive student debt.

“These are complex problems and we need to stop pointing fingers and start working together,” Perry said. “One bill, one change, one new Board of Regents policy isn’t going to solve the problem.”

South Dakota colleges among costliest in nation for net costs

South Dakota’s public university students pay an average of $4,000 more per year more for college degrees than most other public college students in the country, according to a new report.

The report, set to be presented in early August to the state Board of Regents, shows the net cost of attendance at South Dakota’s public universities is the eighth-highest in the nation, said Jay Perry, vice president for academic affairs for the board that governs the state university system.

Net price is the price paid after scholarships, grants and other forms of non-obligation aid are accounted for. The net price South Dakotans pay at their public universities comes in at an average of $16,706. The national average is $12,697, according to the report.

“We’re not only the most expensive in the region on that cost, but when you compare to other states that are in the same ballpark on net cost, it’s the Eastern Seaboard and it’s South Dakota,” Perry said.

In real numbers, the cost to attend the state’s universities is actually below the national average. The total average price of attendance, which includes tuition, room and board, for South Dakota’s universities is $22,393 a year. The national average comes in at about $23,248.

But the lack of a needs-based scholarship and other state-funded forms of financial aid in South Dakota mean the state’s college students are on the hook for a much greater percentage of the price of getting a degree, Perry said.

South Dakota has the third-least amount of state grant money available to its students and the fourth-least amount of grant aid available from university endowments, the report says. Overall, South Dakota has the second-least amount of grant aid available to its students in the nation, the new report says.

The report says the consequences of high net costs already are being felt in the number of low-income students choosing to attend college in the state. The number of recipients of federal Pell Grants that aid lower-income students at South Dakota public universities fell from 31.5 percent in 2010 to 22.5 percent in 2018, the report says.