Trey Wharton of Sioux Falls has made numerous sacrifices in his life in order to maintain a healthful lifestyle centered around a vegan diet and consistent consumption of organic foods.

To afford organic products that are sometimes double or triple the cost of conventionally grown foods, Wharton works two jobs, doesn’t take vacations and drives a dented SUV.

“I’m investing in this vessel,” Wharton said, pointing at himself, “rather than in that vessel,” he added, motioning toward his 2011 Honda. “I pay more and sacrifice to invest my money in the foods I want.”

Wharton, 31, acknowledges that he is forced to trust the organic industry to uphold its promise that the foods are minimally processed, are grown without chemicals or additives, and are truly more healthful than non-organics.

“I don’t have a place in that system, so I have to trust them,” Wharton said.

Like other consumers who buy organic, Wharton sometimes wonders and worries if he’s actually getting what he believes he is buying. He is well aware of a few high-profile cases of organic food fraud — including a recent multimillion-dollar fake organic grain scam in South Dakota — in which unscrupulous producers or distributors made millions of dollars by illegally selling conventional grains packaged and sold as organic.

In the 2018 case in South Dakota, farmer Kent Duane Anderson of Belle Fourche made $71 million in fraudulent income by selling thousands of tons of conventionally grown grain falsely labeled as organic. Anderson then used the proceeds to buy an $8 million yacht, a $2.4 million home in Florida, and a Maserati, among other extravagant items, according to a federal indictment. Anderson is now in federal prison.

In July 2022, a Minnesota farmer was charged by federal prosecutors in a $46 million grain fraud scheme. In a federal indictment, authorities say James Clayton Wolf bought conventionally grown grain and resold it as organic over a period of about six years. Wolf has pleaded not guilty and will fight the allegations in court, his lawyer told News Watch.

Those cases of fraud or alleged fraud have caused uncertainty and mistrust among some consumers in an industry that relies largely on the honesty of producers, processors and packagers to maintain the integrity of the industry and, ultimately, to allow consumers to feel confident they are actually getting organic products for which they pay a premium price.

“If there’s more money in it, there’s more people looking at the dollars aspect and not the moral aspect,” said Charlie Johnson, a longtime organic farmer who grows soybeans, corn, oats and alfalfa southwest of Madison, S.D. “Those types of people and operations need to be pointed out and prosecuted, because they can bring down all of us if we don’t keep the system clean and honorable.”

In many ways, the organic food industry in America — which topped $63 billion in sales in 2021 — is responding to negative publicity from fraud cases and other weaknesses in the organic regulatory system by pushing for more stringent requirements and stronger enforcement of existing rules to protect the industry’s reputation long term.

At the policy level, the organic industry has been pushing for more regulation and oversight from the USDA and Congress to protect the integrity of the industry as it grows and evolves, said Reana Kovalcik, director of public affairs at the Organic Trade Association, a business group representing the organic industry in Washington, D.C.

The group that represents organic farmers, processors and retailers is pushing for new rules and programs to improve transparency, oversight and enforcement of national organic regulations and processes, Kovalcik said.

“It’s kind of unique for an agriculture industry to say, ‘Hey, please regulate us more,’ but that’s exactly what the organic industry is asking for,” she said. “The industry wants to make sure everything is as buttoned up as it needs to be for producers who are doing this extra work to get a price premium, and for consumers who are paying that premium price.”

The organization has separate regulatory and congressional packages it has been pushing for years, but both are bogged down in Washington, Kovalcik said.

One element of the proposals deals with increasing fraud protections within the industry, she said.

As hard as the organic industry tries to police itself and protect its integrity, Kovalcik said she still hears people speak about Randy Constant, the Missouri corn and soybean grower who perpetrated the largest organic grain-fraud scheme in U.S. history. Constant was sentenced to 10 years in prison in 2019 for generating $142 million in fraudulent organic grain sales, which he spent on an extravagant lifestyle. Constant took his own life after being sentenced.

“It’s really in the interest of the entire organic industry to keep our regulations current, modern and transparent for the good of producers, retailers and consumers,” she said. “The organic seal was all about trust and integrity; that’s why we have seals, and the organic industry takes that very seriously.”

Wharton, meanwhile, said he will continue to buy organic and trust that sufficient safeguards and oversight are in place to ensure organic practices are followed and that organic labeling is accurate.

“It’s like when they build a house,” he said. “You have to trust at some level that what they are doing is up to code.”

Billion-dollar industry attractive to fraudsters

As in any industry, the lure of making big money through fraud is enticing to unscrupulous farmers and suppliers who are willing to risk prison to take advantage of weaknesses in the organic system to defraud consumers.

The enticement to commit outright fraud, or just to cut corners or manipulate the system in small ways, is high in the organic industry, where more expensive, more carefully produced final products look exactly the same on the shelves as products that are cheaper and produced with far less-stringent standards and more chemicals and additives.

On a basic level, organic foods are non-genetically modified crops grown in soil without chemical additives such as fertilizers, herbicides or pesticides; and non-genetically modified livestock raised on mostly organic feed without added hormones or antibiotics.

The USDA describes organic farming as “the application of a set of cultural, biological, and mechanical practices that support the cycling of on-farm resources, promote ecological balance, and conserve biodiversity. These include maintaining or enhancing soil and water quality; conserving wetlands, woodlands, and wildlife; and avoiding use of synthetic fertilizers, sewage sludge, irradiation, and genetic engineering.”

The USDA sets forth a host of operating and labeling regulations, including lists of allowable and non-allowable food additives and agricultural practices, as part of its National Organic Program that was established through the Organic Foods Production Act of 1990.

USDA workgroups within the larger program work continuously to consider requests to modify the program and consider new allowable substances and practices to keep the program up to date, though many people and groups in the organic industry say the USDA is too lenient and too slow to react to industry changes.

Furthermore, the organic food industry is relatively new in comparison to the conventional food industry, so regulations have come more slowly and with less consistency and lower government investment and intervention.

For example, the USDA is responsible for setting product-safety and production guidelines for both the conventional and organic food industries. But while the USDA is responsible for regulating and enforcing the rules in most conventional agricultural processes — the meat industry, for example — the USDA outsources the certification and regulatory functions of the organic food industry. In the organic world, producers who want to label their products as organic must become certified by one of about 80 independent groups or agencies, many of them nonprofit groups devoted to promoting organic agriculture. Typically, those agencies inspect producers they certify only once a year, and they are paid for their certification services, creating a potential incentive to maintain a high number of certified producers.

The organic food industry has exploded in roughly the past 30 years as a growing number of Americans and people around the world seek more healthful foods grown with fewer chemicals and less-invasive agricultural practices.

Sales of organic foods have roughly quadrupled in the past 15 yeas, from about $16 billion nationally in 2016 to more than $63 billion in 2021, according to the Organic Trade Association.

South Dakota has been slower than other states to take advantage of the exploding organic market, and is ranked 38th of the 50 states in the number of organic farms. South Dakota’s 124 certified organic farms and related businesses generated $14 million in product sales in 2019, a 42% increase over 2017. However, acres of farmland devoted to organics in South Dakota still make up less than 1% of the overall agricultural land in the state.

South Dakota lags other Great Plains states in organic farming

Here is a look at the number of certified organic crop, livestock or combined farms in South Dakota and in other states as well as the U.S. as a whole in 2019. The chart shows number of certified farms, value of organic goods sold, percent of sales increase from 2017-2019, and national ranking in number of farms.

State Farms Value % Change U.S. rank

Iowa 1,066 $145 million +52% 5th

Minn. 996 $114 million +12% 8th

Neb. 358 $185 million +173% 22nd

Mont. 342 $66 million +162% 23rd

N.Dakota 200 $113 million +108% 31st

S. Dakota 124 $14 million +42% 38th

Wyo. 82 $16 million +45% 42nd

Calif. 5,077 $3.6 billion +27% 1st

U.S. 28,000 $63 billion +2% —

Sources/notes: Organic Trade Association and USDA 2019 Agricultural Census; U.S sales increase shown is for one year (2020-21); some numbers are rounded.

Organic system relies on ‘checks and balances’

Angela Jackson has obtained a close-up view of the organic foods industry from two distinct vantage points: as a producer who owns and operates Prairie Sun Organics certified poultry and crop farm in Vermillion; and as someone with more than a decade of experience as an organic expert and independent inspector who has audited organic farms in 36 countries.

“I have spent my life working with verifying bodies, working as an inspector, making sure that things are done right and bringing integrity to the system,” she said.

And yet, Jackson is aware of the concerns over the integrity of the organic agriculture system in the U.S. and in other countries.

“Within organics, there are people that really know the system and are experts at finding the loopholes in the system and they take advantage of that,” Jackson said. “But 99.9 percent of the time, farmers do a fantastic job, and the good news is that the bad guys get caught, which tells me that the system is working.”

Jackson noted that the certification agencies and most of their employees are well trained in identifying and rooting out fraud or potential fraud. While she acknowledges that more oversight would be good for the industry, she added that organic foods are actually more highly regulated and monitored than conventional foods.

Annual inspections of producers seeking organic certification typically include a review of paperwork, a tour of the farm and farm operations, and testing of products and equipment for the presence of non-allowed substances such as pesticides, she said. Reports developed by on-site inspectors, she said, are then reviewed for accuracy by the certifier’s technical specialist.

“To be qualified to be an inspector is arduous,” she said.

One weak point in the regulatory oversight process, Jackson said, is that most of the testing of organic crops is done to look for genetically modified organisms, which are not allowed. More direct testing of products for the presence of pesticides could be done in the inspection process, she said.

Jackson added that there is a difference between “compliance,” which is following both the letter and spirit of organic regulations, and “ethics,” which puts more onus on the farmer to do what is right even if the rules don’t necessarily call for it.

Jackson said some farmers and livestock producers are beginning to find loopholes in the organic requirements that have been in place for decades, including the growth of hydroponic crops that never touch actual soil. Some farms risk cross-contamination of organic and non-organic products through “dual production” farms, which grow or raise both types of products on the same farm and open the door to reduced integrity of the organics produced there.

“What we’re losing in organics is the ethics piece, and the ethics are getting watered down,” she said. “The compliance piece is still there, but unfortunately some farms are putting corporate interests first, and it’s all about money to them.”

However, Jackson said, the majority of organic farms in the U.S. are both compliant and ethical in how crops are grown and how animals are raised and treated.

But even as she is aware of the weaknesses within the organic certification and regulatory system, Jackson is confident that consumers who desire organic products can rely on the systems in place to ensure safety and authenticity.

She also urged a consumer who questions the validity of a claim of organic on any product to take a picture of the product and submit it to the USDA for investigation. Getting to know local food producers personally is another good way consumers can ensure they are getting the organic products they expect, she said.

“Could there be more enforcement officers with the USDA, and could there be more auditors like me doing this work, yes, there could be,” she said. “But generally, organic farmers have a heart to do the right thing, and there’s checks and balances in the system so it works very well.”

“You can be assured that when you buy a product, it has 95% less pesticides than a conventional product, because we can never get to 100%,” she said. “More than 90% of the time, however, we have total confidence, and if it’s made in the USA, and it’s certified in the USA, you can be highly confident the organic product is what it says it is.”

Organic industry focuses on integrity

In many ways, the organic food industry is taking new steps on its own to further protect the relationship of trust it has with consumers, to assure them what they’re buying is what they’re getting.

Abby Lundrigan is driving across the American Midwest to meet with organic farmers to examine their practices to see if they qualify for a so-called “add on” organic certification.

Lundrigan, a former organic farm manager, is a certification liaison for the Real Organic Project, a Vermont-based nonprofit organization that seeks to provide organic farmers who meet their standards a way to further identify their products as approved by the organization.

The add-on labeling — provided free to qualifying farmers — is one way some organic producers are trying to retain and bolster their integrity and credibility with consumers at a time when the organic industry has been plagued by occasional cases of fraud, sidestepping of basic organic farming principles and watering down of federal organic standards.

The group’s literature said it was created because while USDA organic certification is important, it has become weakened to the point where many organic farmers feel it can be manipulated or abused by farms and operators who don’t follow some of the original tenets of organic farming.

For example, the group points out that the USDA allows organic certification of farms that use hydroponics, or soil-less growing methods, and allows certification of cattle and poultry farms known as confinements, where animals are not allowed onto pasture land and are not free to move about in the outside air.

“The growing failure of the USDA to serve and protect organic farming was the catalyst that united us,” the group says in its literature. “The farmers of the Real Organic Project have created an add-on label to USDA organic to differentiate organic food produced in concert with healthy soils and pastures.”

The group further states: “As organic succeeded, the same big players in chemical ag became the big players in the organic industry, and with this big tent, we suddenly found the tent changing. Soon we could barely recognize as ‘organic’ much of what was being sold under our label.”

Since launching in 2018, the Real Organic Project has certified more than 850 farms to use its add-on labeling.

Lundrigan said that while outright fraud within the organic industry may be rare, examples of minor manipulations of the system, though still rare, are more common than Real Organic Project would like.

“Once the organic industry became a multibillion-dollar industry, somehow a lot more organic food ended up on the shelves but somehow there’s not any more organic farmers producing it,” she said.

High-profile incidents of organic-grain fraud not only hurt consumers who didn’t get the organic grain they assumed they did, but also cause fundamental damage to the reputation of the industry and farmers who are doing things right, Lundrigan said.

“I think customers are starting to learn that when they go to the store, that flour they are paying more for isn’t necessarily grown the way they think it was,” she said. “And as people are starting to think that, it’s really harmful to organic farmers that are really doing it the right way and are suffering from that growing mistrust or erosion of trust.”

On a recent trip to South Dakota that included a visit to Charlie Johnson’s farm, Lundrigan said she knew of organic milk producers who mixed organic milk with conventional milk and labeled it organic. She told of berry producers whose plants never touched soil yet were allowed to be labeled organic.

Real Organic Project, she said, will not certify hydroponic farms or those that raise animals in confinement. And some grain operators and handlers do not do a good enough job of cleaning out residue from conventional grain before storing organic grain in elevators, she said.

Real Organic Project requires that crops be grown in real soil that is well managed, and requires that livestock and poultry live in pastures rather than in confined spaces.

The add-on label, Lundrigan said, “is free and meant to distinguish farms that are legitimately organic. It’s a label largely focused on that trust element we need to have with consumers, a trust element that is foundational to the success of the organic industry.”

Putting the farmer back in farming

It only takes a few hours of visiting with Charlie Johnson and driving in a pickup around his farm in Lake County, S.D., to realize why organic grains cost more than conventionally grown grains at the wholesale and retail levels.

Johnson and his family members have been growing and harvesting organic grains since the 1980s, and Johnson has emerged as a leader in mastering the processes of organic farming and as a promoter of the organic-farming lifestyle and its values.

On a more philosophical level, Johnson sees organic farming as a return to the roots of agriculture — in which farmers didn’t rely on chemicals, huge machines or vast economies of scale to drive production and profits, but rather lived on the land, spent many hours working the land, and used their minds to determine the most efficient, purest way to grow healthy crops.

“In modern agriculture, we’ve taken the farmer out of farming,” Johnson said. “If we want more community here, more churches, more schools, and a healthy economic environment, organic farming will promote that because it requires human and farmer input. It’s about consumers supporting a family-friendly, community-friendly, soil-friendly and health-friendly approach to farming, and they want to put their dollars behind that.”

To uphold that strong connection between earth, farmer and consumer takes a lot of thought, planning and hard work.

Johnson has 65 separate fields of crops on his 1,600 tillable acres, and he uses a six-year rotation of crops, in which each year a field has a different crop grown on it to promote soil health.

Instead of herbicides, he must drive a cultivator over his crops to remove as many weeds as possible from the land between crop rows. About 5% of his land is preserved as buffer strips and shelter belts that form a natural barrier between croplands and between his organic crops and those of neighboring conventional farms to block chemical drift. Signs are placed in ditches along his crops so pesticide contractors hired by conventional farmers do not apply chemicals to Johnson’s crops by mistake.

Johnson has no doubt that the resulting products are not only different, but also better than conventionally grown crops.

“I just think organic foods are simply better; they’re very much richer and better in quality and in food density,” he said.

His efforts make it slower to develop yields but he’s rewarded with higher prices when he sells them to a certified organic wholesaler. In mid-July 2022, Johnson was able to sell soybeans for more than $30 a bushel while conventional soybeans were bringing about $14 a bushel. His organic corn was selling for about $10 a bushel compared with the roughly $6.50 per bushel price being paid for conventional corn.

While Johnson acknowledges he has been successful in organic farming, and makes “a decent living,” he is still eager to learn more and try new things.

He is working with researchers and students from South Dakota State University to plant numerous small test plots on his land to see which crops grow best in particular conditions and settings. He is trying a new way to regenerate soil by cutting down and mulching small alfalfa plots and leaving the crop to decompose where it lies. He hosts regular farm tours and visits to educate the public about his operation and the value of organic farming.

“Putting the whole argument that organic is better for the environment off to the side, I would say it’s more community-friendly, because what you do in organic farming has a greater emphasis on the farmer and the farm and the management of the land.”

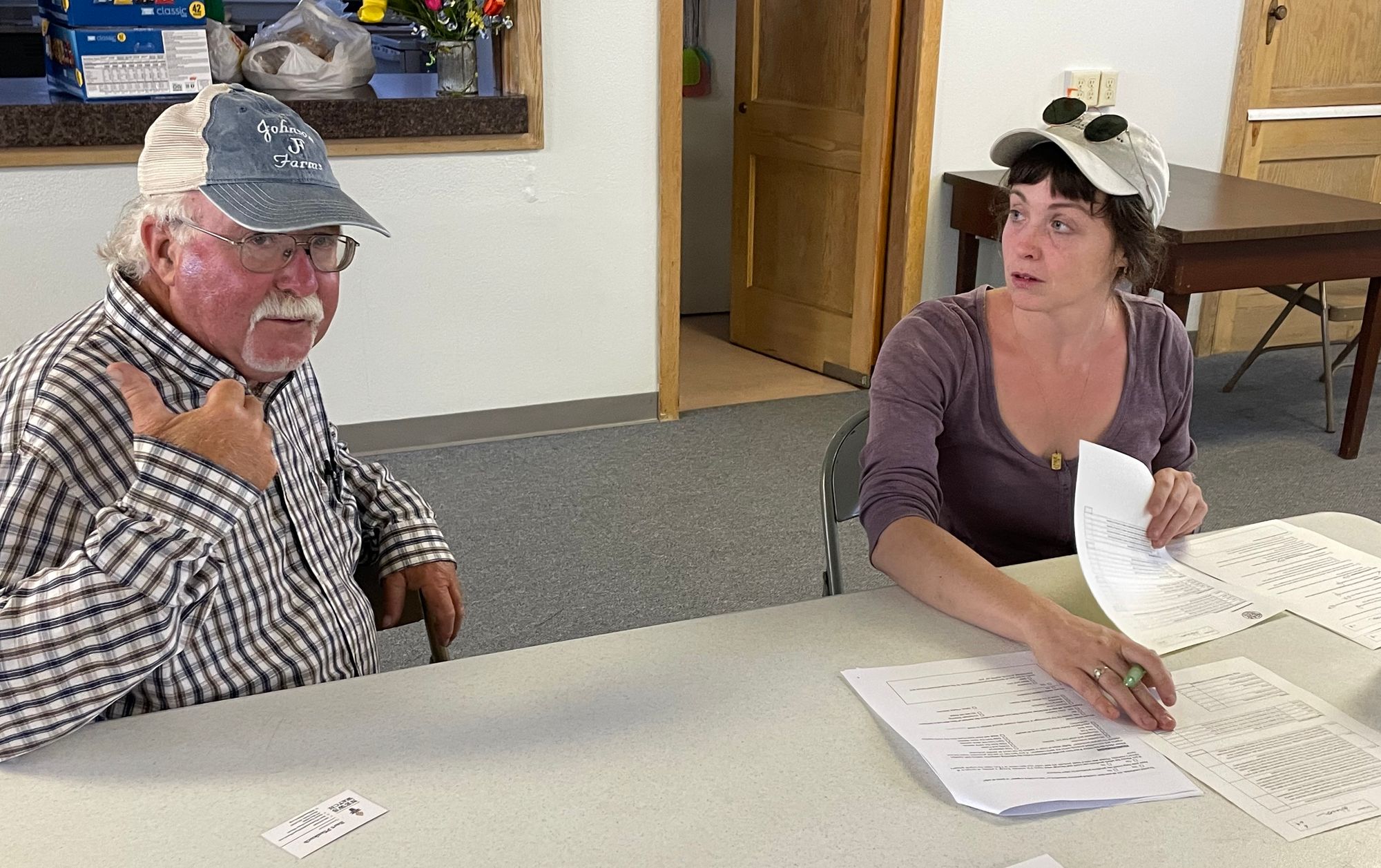

In mid-July, Johnson answered a series of questions from Lundrigan, of the Real Organic Project, and gave her a pickup-truck tour of his farm. After the initial examination, Lundrigan said, it appeared that Johnson Farms was highly likely to qualify for the add-on organic label.

Epilogue: Wharton’s sacrifices take a toll

In mid-July 2022, a South Dakota News Watch reporter met and spoke with Trey Wharton as he arrived at the Sioux Falls Food Co-op to purchase some organic foods for the next few days.

Wharton told of some of the financial and lifestyle sacrifices he had made to keep up his more expensive organic vegan diet.

“I sacrifice having money to go on fun trips I see everyone on social media doing, being able to have enough to keep up with rent and bills, not being able to save money, and not being able to buy fun things like roller blades or new research books,” he wrote in a Facebook message. “I’m always living day-to-day, buying food for the day or maybe the next two days based on the amount of tips I get and how far I can stretch my paychecks.”

Two weeks later, when News Watch contacted Wharton to clarify a few things, the 31-year-old shared some bad news.

Although Wharton said he has a full-time job as a delivery driver for Pizza Ranch in Sioux Falls and works part time as a package handler for UPS at the Sioux Falls airport, the pay from his 55-hour work week wasn’t enough to pay the rent.

“I’m now living in my car because my rent was behind and they non-renewed my lease so I’m now living the ‘van life,’” Wharton wrote to News Watch. “But at least I have my health. Ha.”

Asked if he was willing to share news of his recent homelessness with the public, Wharton wrote back that he is willing to give up basic comforts in order to sustain his healthful diet, including living for a spell in his 2011 Honda CRV.

“I’m cool with it — it shows the math of how hard it is to eat this way,” he wrote, “and what someone might need to sacrifice to try and regain their own health.”