Two seemingly harmless words added to a state open meetings law in 2019 have sparked a debate over the rights of citizens to publicly comment at official government meetings in South Dakota, with several school boards at the center of the conflict.

The state open meetings law, enacted in 1965, was amended in 2018 by House Bill 1172, which required every official meeting to offer a period for public comment under the discretion of the chair. One year later came Senate Bill 91, which clarified language and put public comment at the discretion of the entire body rather than just the chair.

As part of that process, the words “regularly scheduled” were added in front of “official meetings,” which bore little scrutiny at the time but has launched a legal tug-of-war between public officials and advocates of community input. Some government bodies have used the language to create a legal loophole in which they have denied the public the right to speak at official meetings.

Different interpretations of the wording stirred controversy last month in the case of a Garretson High School principal and football coach, whose contract was terminated by the school board after more than five hours of closed-door deliberations. Some community members felt stifled by an inability to address the board.

Across the state, an unsuccessful lawsuit against the Rapid City Area Schools Board of Education over the infringement of public comment has been appealed to the South Dakota Supreme Court, fueled by a group of parents who claim they were denied a voice as the board weighed disciplinary action last year against a high school wrestling coach and his staff.

House Bill 1255 was introduced in the 2022 South Dakota legislative session to clarify the principle that public comment must be permitted at all official meetings of public boards. The bill was killed in committee, though opponents acknowledged that clarification in the language of the existing statute is needed to avoid open meetings violations.

“In the municipal world that I operate in, I would be very hesitant to not allow public comment at an official meeting,” Sam Nelson, a lawyer and lobbyist for the South Dakota Municipal League, said at a House hearing on the proposed bill. “I think it’s almost a blanket statement that I would never recommend that.”

Critics of the existing law say that public bodies such as school boards, city councils and county commissions are being allowed to exclude public input because of a semantic loophole cited as justification for doing public business without taxpayer input, and it comes down to those two words.

Garretson schools Superintendent Guy Johnson, in an interview with South Dakota News Watch, cited the “regularly scheduled” wording when asked why supporters of principal and football coach Chris Long were not allowed to address the board at a special meeting held Feb. 23 to determine Long’s fate.

“I would refer people to the law, which deals with public comment at regularly scheduled official meetings,” said Johnson. “This was a special meeting for a specific purpose, and the language does matter. People in the community are going to be upset either way, because they believe they’re entitled to know all the details in these types of situations, and that’s simply not the case.”

Rapid City case heads to high court

The lawsuit in Rapid City stems from a group of parents upset over the termination of Rapid City Central High School wrestling coach Lance Pearson over alleged violations of COVID-19 protocols involving an assistant coach, though Pearson was later reinstated. Joined by South Dakota Citizens for Liberty, a nonprofit group, the parents claimed that the school board stopped allowing for public comment at all meetings beyond the twice-monthly sessions that were “regularly scheduled” each year in July.

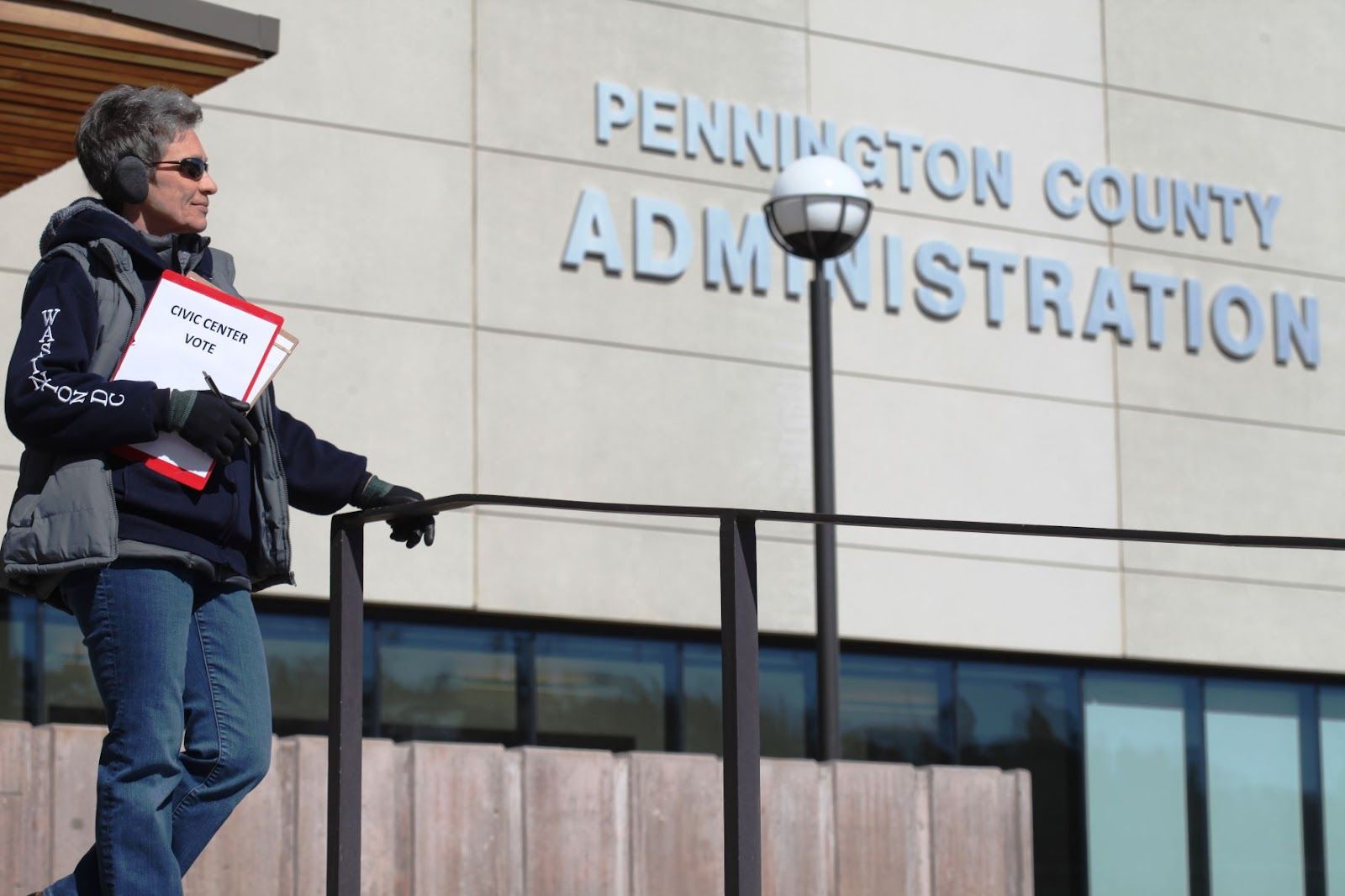

“This is a hill I’m willing to die on,” said Tonchi Weaver, a lobbyist and organizer for South Dakota Citizens for Liberty. “The public is reduced to being mere spectators if all they can do is come and listen to the body deliberate. We should allow citizens to have the opportunity to address the people they elect to office.”

Kenneth “Chuck” Jasper, a Rapid City attorney representing the group, will ask the state Supreme Court to consider whether school boards should be able to use study sessions, work groups, retreats, and other types of meetings to avoid public dialogue on critical matters.

“If we don’t force public bodies to follow the law, they’re not going to do it,” said Jasper, who helped craft the 2022 bill that attempted to resolve the issue. “Why hide your light under a bushel? Public business should be conducted out in the open.”

Opponents claimed that this year’s bill, sponsored by Rep. Steve Haugaard, R-Sioux Falls, was marred by an amendment that sought to restrict comment to “only taxpayers or residents of a political subdivision or a parent.” Several legislators commented that simply striking the words “regularly scheduled” from the existing statute might have been all that was needed.

Rapid City School Board President Kate Thomas, speaking in a personal capacity, testified in favor of the bill, confirming that the board’s stance on public comment changed once its legal counsel noted the new wording in the 2019 measure. The board has maintained that its policy follows the letter of the law.

Most agree that the compact between school board and community can be colored by conflict, especially when hot-button issues arise. There were reports nationally of school officials or board members being threatened by community members during COVID-19 mask discussions, prompting U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland to issue a memo saying such incidents “run counter to our nation’s core values.”

Wade Pogany, executive director of the Associated School Boards of South Dakota, said that open dialogue can help defuse the tension on controversial topics. He noted that the Mitchell School Board held meetings at the Corn Palace last August to accommodate those who wanted to address the district’s proposed mask mandate. Testimony was heated, sometimes even hostile, but the input was heard before a vote took place.

“Every community has topics that are emotional,” said Pogany. “But it’s wise for a school board to have those open discussions so that the frustrations and emotions have an outlet and don’t manifest themselves in some other way.”

Matters of public trust in Garretson

At around 5:40 p.m. on Feb. 23, a freight train rolled slowly along the outer edges of Garretson, about 20 miles northeast of Sioux Falls, and came to a stop, causing a backlog of vehicles at the crossing that leads into town.

It was an ominous sign for those seeking access to a 6 p.m. school board meeting focused on potential action against Long, the high school and middle school principal and head football coach, who had stopped showing up for work due to suspension in early January.

His absence was not officially acknowledged by the school district for nearly a month, when an article by Garrick Moritz, editor and owner of the Garretson Gazette, entitled “Why has Chris Long not been on the job?” triggered a Feb. 3 text message from Superintendent Johnson to parents. The message confirmed that Long was “absent from his duties” but that the administration was prevented from saying more because of federal and state statutes and “basic human decency.”

Asked by South Dakota News Watch if a cursory announcement several weeks earlier saying Long had been suspended pending further review could have reduced tensions, Johnson defended his policy. “In my opinion,” he said, “the time when there’s a need for notification is when any students are in danger, and that wasn’t the case.”

For Moritz, it was reminiscent of a situation involving former Garretson boys basketball coach Nate Beckman, who disappeared from his duties during the 2018-19 season without public acknowledgement from the administration. At the time, Johnson refused to answer questions from the local newspaper.

The day after Moritz approached Johnson for comment, notice of a special school board meeting was posted, where community members showed up ready to speak, though they were denied that opportunity. “We’ve got a lot to get through tonight, and I think we know why everybody is here,” School Board President Shannon Nordstrom said, adding that comments on the sign-in form would stand as public commentary.

The board went into executive session but never issued a ruling, and Beckman was back coaching the team the next day. He left the school district after the school year along with his wife, Stacey, who served as head volleyball coach.

If the episode with Beckman caused ripples of concern in the community, Long’s suspension rocked its core. The Wessington Springs native, a former standout high school and college athlete, arrived at Garretson in 2008 and soon became entrenched in the school community, with a son and daughter involved in varsity athletics.

As frustration with his absence mounted, students wore T-shirts with pro-Long slogans to basketball games and used social media to criticize the administration’s actions. A small group of students also staged a “sit-in” protest during school hours and were punished with weekend detention.

Tensions carried over into a Feb. 14 “regularly scheduled” school board meeting, with attendees filling the school library. Nordstrom noted the unusually large gathering but explained that it was a “board meeting in public…not a public meeting, where people would be invited to speak.” The board allowed Tana Clark, who spearheaded a petition that gathered more than 100 signatures in support of Long, to read a statement, and then went ahead with board business not concerning Long without further public input.

By the time the scene played out again for the Feb. 23 special meeting, the board had appointed Huron attorney Rodney Freeman as hearing officer and legal counsel, while Long was represented by Sioux Falls lawyer David Kroon. Johnson sat with Sam Kerr, the school district’s attorney, who assisted with the administration’s internal review.

The focus of Long’s suspension was on the aftermath of an altercation, and ultimately an assault, between Garretson student-athletes while attending a track meet in Baltic the previous spring.

The boys were throwing an apple back and forth when one of the students hit then-senior Dominic Abraham with an apple in the face. According to an arrest affidavit filed by the Minnehaha County Sheriff’s Department last July, Abraham (the only student who was 18) and three other boys chased the eventual victim, who was knocked to the ground. The victim claimed that Abraham then took a stick and stuck it into the victim’s rectum while he was still wearing sweatpants, later claiming that “he could not move at all during the assault due to the amount of force used by the boys holding him down,” according to the affidavit.

The detective recommended charges of simple assault and second-degree rape with an object, but Abraham was charged with simple assault and pleaded guilty to the misdemeanor in early January. He graduated from high school last spring. Other students involved in the incident were minors and returned to school in the fall. Their names are redacted in the affidavit.

Johnson didn’t find out about the incident until late August, and a legal review scrutinized the actions of those who knew about it earlier. Under Title IX and state law, school officials are mandatory reporters required to report to proper authorities “instances where they have reasonable cause to suspect that a child under the age of 18 has been abused or neglected.” Students other than Dominic Abraham ended up disciplined by the school for their actions.

“There was a lack of communication between a lot of people,” said Tom Long, Chris’ father, a longtime educator and coach who served as volunteer football coach at Garretson the past six years. He joined his wife and other family members and supporters the night of Feb. 23, waiting five and half hours in the school commons as the board reviewed evidence and heard testimony, with black construction paper taped up to cover the library’s glass doors.

“I’m not stomping my feet about the whole thing,” Tom Long added that night. “There are things that could have been done differently, but Chris is a kind-hearted guy. He thought he was letting the legal system run its course.”

Chris Long and his attorney were gone by the time the doors opened around 11:20 p.m. and Nordstom called a somber board back to order. There was a motion to terminate Long’s contract based upon “a clear failure to follow, and violation of, the district’s policies and procedures,” and it passed unanimously. The fate of his teaching certificate rests with the South Dakota Department of Education, which has not yet announced any action.

The remaining supporters shuffled silently out of the library and into the school foyer, some of them weeping. Tom Long and his wife embraced Chris’ son, a junior at the school, as students in “Long Strong” T-shirts walked to the exits. Nordstom refused to speak to the media that night, instead releasing a statement the next day.

Johnson was asked a week later about ill feelings in the community, including suggestions among Long’s supporters that families might opt to leave the district because of the way the situation was handled.

“Our goal is to have a safe and positive learning environment for all of our kids, and we’re going to move forward with that mission,” said Johnson, who came to Garretson in 2014 from West Central, where he served as middle school principal. “It’s up to individuals who make up the community whether they want to continue with that or not. There are always some who hold onto (grievances) or get angry, but for the most part people come to the realization that we’re all working toward the same goals.”

From a media perspective, where transparency is critical, Moritz sees things differently. Recent brushes with school officials in Garretson have convinced him that things need to change in order for the community to truly thrive.

“As a reporter, you want to trust the process, you want to trust the people involved,” said the Augustana University journalism graduate, who has owned the Garretson paper for seven years. “If we want to move forward as a community, we have to have clear and precise transparency. That’s the same thing the superintendent and board have said numerous times at meetings I’ve attended, but you’ve got to walk the walk.”

South Dakota laws limit openness

State law allows public bodies to hold closed meetings in executive session when discussing personnel matters – “discussing the qualifications, competence, performance, character of any public officer or employee” – as well as consulting with legal counsel, contract negotiations, marketing or pricing strategies and certain deliberations involving high school students.

But not all nearby states treat personnel issues as a complete blackout of information from public and media. In Minnesota, closed meetings are permitted for “preliminary consideration of allegations or charges against an individual subject to its authority.” But if members determine that discipline might be warranted, “further meetings or hearings relating to the charges must be open.” Most states require that closed meetings be electronically recorded in case a legal challenge arises, but South Dakota’s statute has no such provision.

Too often, according to David Bordewyk of the South Dakota Newspaper Association, officials use the privacy provision reserved for personnel as an excuse to shield themselves from public scrutiny.

“That’s a weakness in the law,” said Bordewyk, who lobbies for free speech issues in Pierre. “Schools are quick to clam up and say nothing if it involves personnel, which frustrates not just the press but the public. They sit there for hours on end waiting for smoke to come out of the chimney or doors to open to find out what the hell is going on.”

Cynthia Mickelson, president of the Sioux Falls public school board, points out that there are other avenues of accountability that run concurrent to district deliberations, such as criminal or civil proceedings, that need to be respected.

The Department of Education started a database last year that lists teachers whose teaching certificates have been revoked and the reasons behind the action, adding a level of transparency on the back end of personnel deliberations.

Complaints about transparency involving public bodies can also be forwarded by a state’s attorney to the state’s Open Meetings Commission, comprised of five state’s attorneys, which examines whether a violation occurred and provides a written report.

The Sioux Falls School Board allows public comment at its twice-monthly meetings and at work sessions, with comments at work sessions restricted to the topic at hand. Mickelson notes that board members also field “hundreds of emails and phone calls” from constituents, adding that the intensity of that correspondence heightened considerably during the district’s deliberations on masks and other COVID-19 protocols.

“Since we’re the most local level board, none of us are serving for the glory of it, and people are going to feel comfortable expressing how they feel in a very unvarnished manner,” Mickelson said. “We thought the district boundary process would be the most heated topic we’d face, but that paled in comparison to what we encountered during (the pandemic). Luckily, as a board, we were unified and believed what we were doing was right.”

Allowing for dissenting voices and the free flow of information – even when a public body in unified in opposition – is the spirit of the state’s open meetings law. Tailoring the exact wording to meet that objective is a challenge that will likely resume next year in Pierre, with even more stakeholders involved.

“Any time you want to amend open meetings law, it brings everyone to the table,” said Bordewyk. “School districts, city, county, state – they all sort of get nervous when you start talking about amending the law, particularly as it pertains to executive sessions. The truth is that many of them like things just the way they are.”