TEA, S.D. – Greg Sands spent the longest night of his life at a federal prison in Oklahoma, running out of chances as the darkness rolled in.

He was 31 years old and facing a 10-year sentence for cocaine distribution in South Dakota after years of reckless behavior and a rock-bottom sense of self-worth.

Sands, these days a major player in the Sioux Falls construction trade and a member of the South Dakota Hall of Fame, was a newly arrived inmate at the crowded El Reno correctional facility that night in 1989.

Placed on a cot on the fringes of the cell block, he listened to the slamming of steel doors and wailing of inmates as he lay weeping, snowflakes fluttering from broken windows above.

“I was terrified,” said Sands, 66, who later appealed his sentence and was released after two years to deal with drug and alcohol addictions. “I had all the feelings you would expect from a man who had ruined his life.”

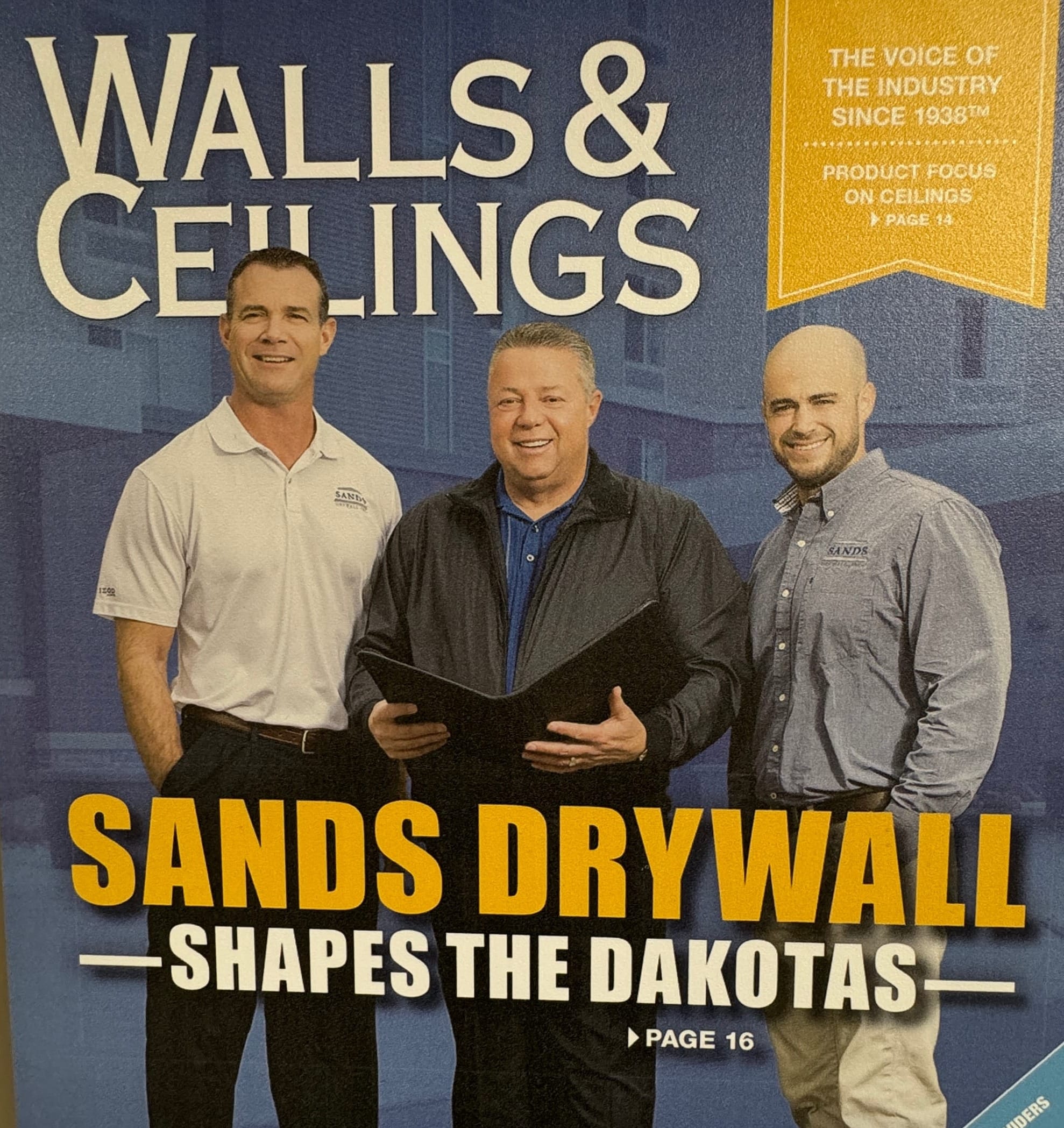

The story of how Sands found daylight and built Sands Wall Systems – a drywall and framing company based in Tea that has 80 employees and helped construct the Washington Pavilion and Sanford Pentagon – has the makings of a messy American dream.

It’s a tale fully embraced by its hero, who on a December morning tooled around company headquarters in a red sweatshirt adorned with a Christmas tree, chatting with employees and preparing for the annual holiday party.

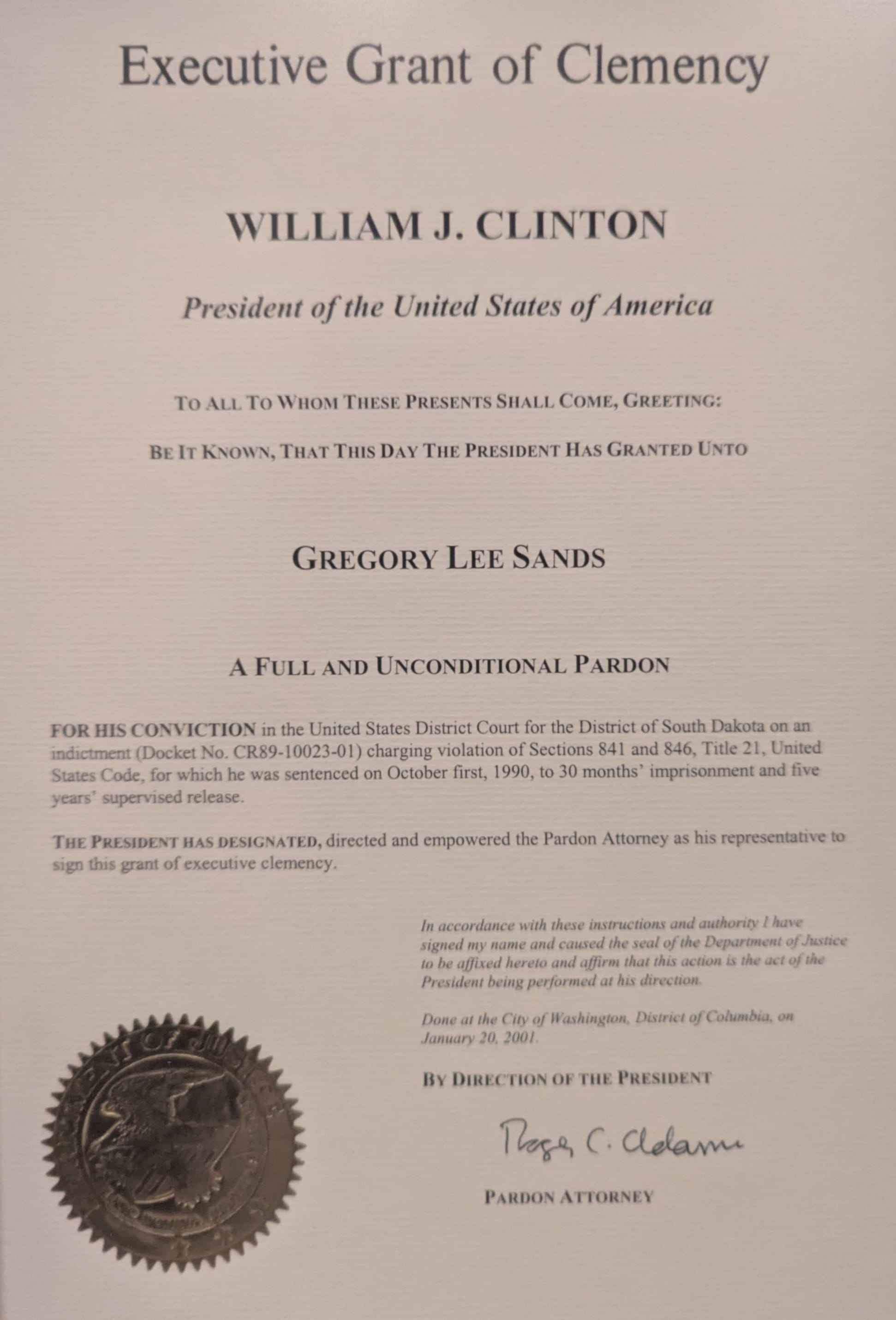

Sands spoke of forgiveness, symbolized by the presidential pardon he received from former President Bill Clinton in 2001, a point of pride along with 33 years of sobriety.

It extends to the philanthropy that Sands and his wife, Pam, embrace through organizations such as the Glory House, a halfway house for recently released inmates, and Feeding South Dakota, the state’s largest hunger relief organization.

Dave Johnson, now a family friend, was a Glory House counselor in 1989 when Sands was taken from the facility in shackles after violating conditions of his pretrial detention.

Johnson was running the place decades later when Greg and Pam helped fund a residential treatment center for women and handed out $50 bills to Glory House residents each December to celebrate the holiday.

“They were able to buy presents for their kids,” Johnson said of the residents. “Many times I heard them say that it was the best Christmas they ever had."

Setting aside the shame

Sands’ ability to understand hopelessness helps him address it.

Just like forging a multi-million dollar business from the back of a pickup truck helped him navigate the upper reaches of Sioux Falls development while expanding into Rapid City and North Dakota.

One thing his story needs is an ending, and he’s preparing for that as well.

Sands, whose previous 290-pound frame is down to 185 after dietary changes and medication, is recovering from prostate cancer surgery in October that sapped his formerly boundless energy. He also takes medication for mild anxiety.

His drywall company, which expanded to steel stud framing two decades ago, recently completed a process to shift ownership from Sands to his employees, with the transfer becoming final after 10 years.

The phasing-out has already begun.

Greg and Pam spend much of their time in Palm Springs, California, but they weren’t about to miss the Christmas party and distribution of holiday baskets to customers. There's meatloaf and mashed potatoes on the menu at headquarters in Tea, "true South Dakota cuisine" according to Sands.

It’s a chance for the CEO to slow down and appreciate how far he’s come, but he can’t stop moving, low energy or not. He rarely stops talking.

He shows off the factory, where workers load sheets of steel into a machine that forms frames and joints for commercial and recreational projects.

He name-drops presidents and governors and business elites, noting that several are close friends. He says he hopes to meet Clinton to personally thank him for the pardon at the planned July 4, 2026, grand opening of the Theodore Roosevelt Presidential Library in Medora, North Dakota, which Sands' company is helping build.

If Hollywood ever makes a movie out of his life, Sands tells people, that could make a compelling final scene.

He's come a long way from that night in the prison cell block, but he hasn’t forgotten it. He still flinches when a prison door slams in a movie or TV show. He thinks often of those who have not yet escaped the swirl of addiction.

How much success is enough to leave one's struggles in the past?

“He still feels shame about it,” said Pam, his wife of 29 years. “He's always trying to prove himself and show that, you know, 'I'm not that guy anymore. I'm somebody.' And I tell him, 'You don't have any more to prove, Greg. You've done great. You’re awesome.' But I think that it’s always there.”

An early start on addiction

Sands' restlessness took root in a place he tried to call home. Greg and his older brother, Dunn-Barr, were raised by their mother, Phyllis, in south Minneapolis in the early 1960s.

“My father abandoned us when I was a year old,” Greg said. “When I was 11, I talked to him on the phone. He was living in St. Louis Park, about a half-hour away. We set up a time for him to come over, and he never showed up. That was the last time I ever talked to him.”

Greg and his mother and brother might have endured if not for a fourth presence in the household, Phyllis’ boyfriend, who was physically abusive to her and her sons.

By the time Greg’s grandfather came to move the family back to South Dakota in Aberdeen, near Phyllis’ hometown of Britton, the boy was 13 years old and already experimenting with booze and pot.

Three years later, in 1974, he was arrested for shoplifting Pink Floyd albums and sent to the Plankinton Boys School, a juvenile correctional facility located about 25 miles west of Mitchell.

The analytical skills that later helped him scan construction blueprints without formal training allowed him to meet the educational standards required to begin the next chapter of his life.

“I tested out right away,” said Sands. “And I never went back to school.”

Taking pride in hard work

He talked his grandmother into helping him get a loan for a motorcycle, a mode of escape that propelled him west to Rapid City at age 17.

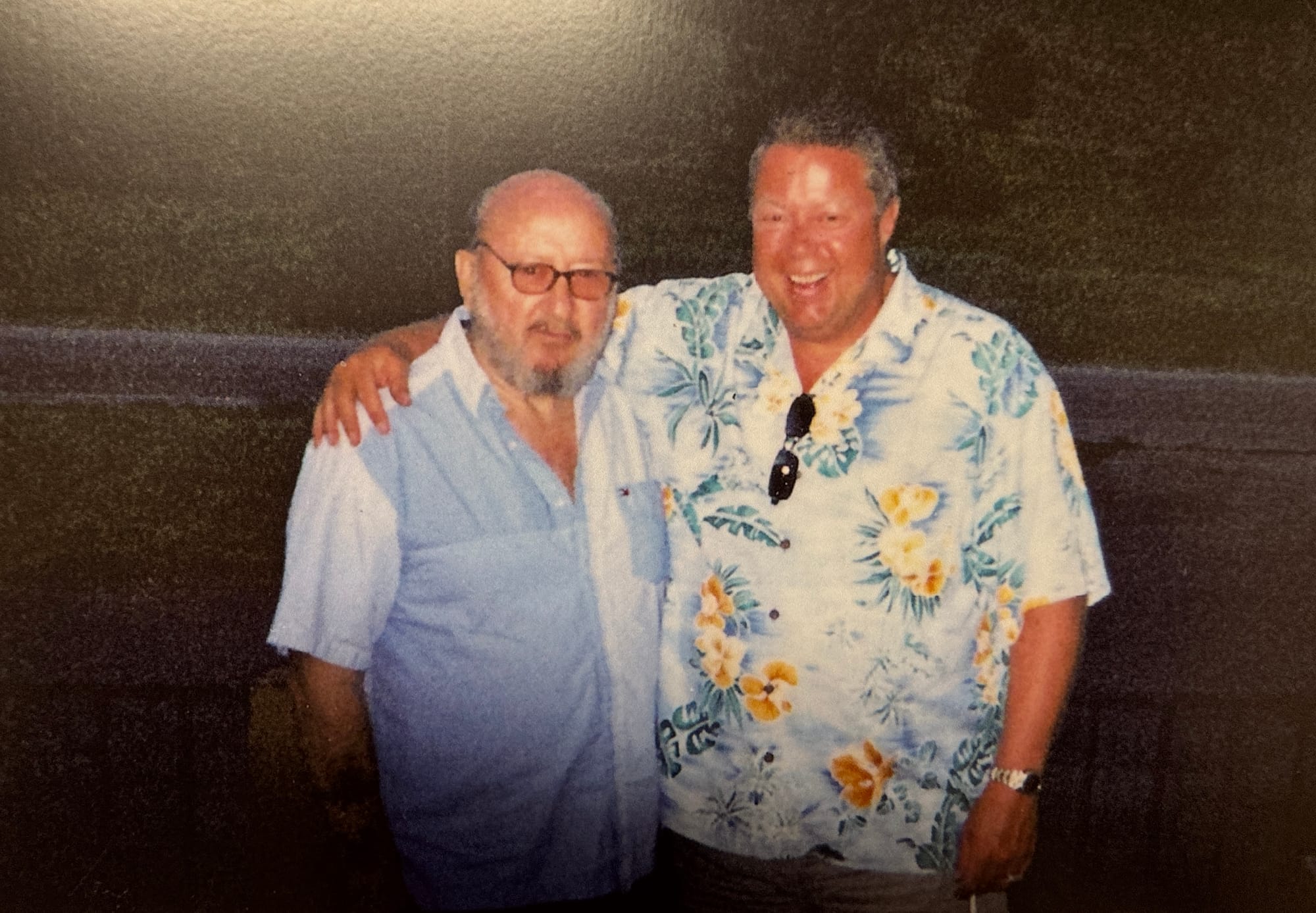

There he forged an alliance with Benny Goldade, an established drywall contractor and the uncle of a friend from Aberdeen. The more he taught Sands the trade, Goldade figured, the less time he would spend on the job himself.

“He trained me so that I could take a job from cradle to grave on my own,” Sands said of Goldade, who died in 2017. “I was a finished drywaller within a year, which is like three times faster than normal.”

It was painstaking work, measuring and cutting wall panels to attach to studs and preparing them to be painted. But it paid well and allowed Sands to drop everything at the end of the shift and get loaded, which became his routine.

“There’s something to be said for being a tradesman,” he said. “You can go anywhere that there's work and get hired tomorrow, and there’s pride in that. No one cared what you did off the jobsite, as long as you showed up in the morning.”

'Most addictive drug in the world'

After five years in Rapid City, Sands took his trade to the Denver area, living and working in Boulder, Breckenridge and Winter Park. It was there that he discovered cocaine, which became more widespread in the late 1970s.

“It started as a love drug in California, where people thought it was nonaddictive,” said Sands. “A few years later, they saw people living in cardboard boxes and said, ‘Well, maybe we got that wrong.’”

By the 1980s Sands had moved to Los Angeles, showing off drywall skills with a bazooka, a specialized tool that applies drywall tape and “mud” (joint compound) at the same time for faster finishing.

“I went to a 14-story high rise on Wilshire Boulevard and they put me in charge of the whole freaking job,” he said. “I had never touched a steel stud in my life, but I was able to visualize what needed to be done for this tenant buildout. All the 50-year-old carpenters hated me for being a 26-year-old in charge.”

In his free time, Sands went from snorting cocaine to smoking crack, which he calls the “most addictive drug in the world.” Fueling his drug habit meant making numerous trips into some of Los Angeles’ seediest neighborhoods.

“I was there every four hours, because you’re only going to do 80 bucks worth, and then you’re going to quit,” he said. “You run home, smoke that, and then run back to get another 80 bucks worth. That cycle plays out until you run out of money.”

The end of his California stay came when Sands broke the cardinal rule: He didn’t show up for work in the morning.

“We were doing a big downtown job at the Hope Street hospital,” he said. “There’s 50 men on the job, and I’m running it, and I'm not there. So now we’ve got 50 guys showing up to a jobsite with no direction, just spinning around, and that cost the company money. So I got fired.”

An 'unsuccessful drug dealer'

In 1987, Sands entered a Scientology-affiliated drug treatment plan called Narconon to address his cocaine problem. But the treatment didn’t hold.

When he returned to Aberdeen two years later to help care for his mother, he brought his drug habit home with him.

His supplier in Los Angeles, a fellow South Dakota native, began sending packages of cocaine through United Parcel Service to Sands in Aberdeen, where drywall work became secondary to using and selling drugs.

“Drywalling was just a cover,” Sands said. “I would spray mud on my arms and go down to the Circus Bar and have drinks at 10 in the morning, acting like I just got off a job site.”

A friend in Aberdeen was a UPS driver, ensuring that the packages weren’t inspected too closely. When asked about what later became known as a drug distribution ring in northeast South Dakota, Sands chuckled.

“There was no distribution. There was consumption,” he said. “Whatever I got, I used about 60% of it myself and sold the rest to a guy who cut it (added substances to increase bulk), and later I would buy it back because I ran out of mine. It wasn’t a smooth operation. I was the most unsuccessful drug dealer I’ve ever met.”

Missteps lead to FBI arrest

The party ended with a series of missteps that could have been written as a screwball comedy if not for the grave consequences involved.

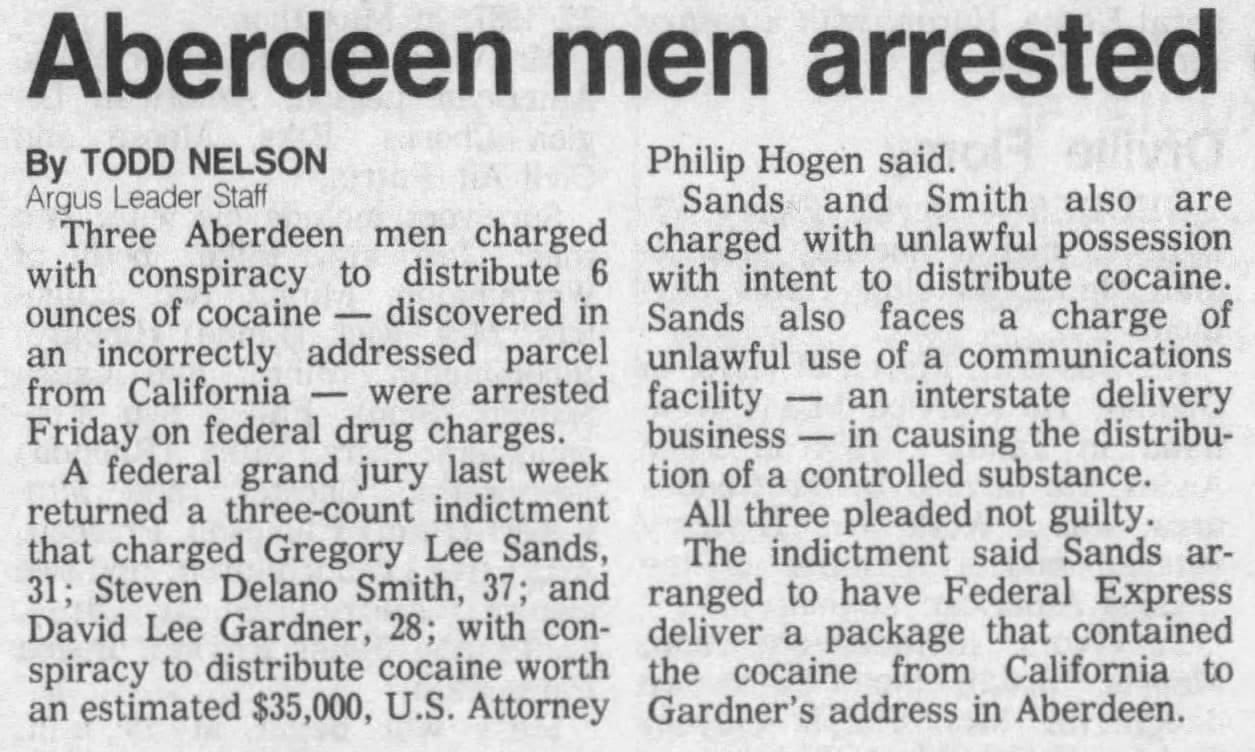

Sands’ supplier in California, for some reason, used Federal Express instead of UPS and penned the delivery address in a manner that complicated shipping.

“The last number in the address was supposed to be a zero, but he put a little loop in it that made it look like a six,” said Sands. “It came off as an address that didn’t exist.”

The return address was fake, so FedEx workers opened the package and discovered the drugs. They notified law enforcement, whose investigation was aided by the fact that the package contained the phone number of one of Sands’ associates.

Working with the FBI, FedEx workers called that individual and asked him to come pick up the package on April 10, 1989. Sands followed in a car behind him, suspicious of the circumstances but still wanting to acquire the drugs.

“I drove down the road a bit and came back around, and the FBI had him on the ground in front of the FedEx place,” said Sands. “I left town, got drunk and then called my lawyer, who said, ‘Greg, this is bad. You’ve got to turn yourself in tomorrow morning.’”

'Large-scale' drug operation

The drug bust made regional headlines that summer, when Sands and two other defendants pleaded guilty to conspiring to distribute 6 ounces (170 grams) of cocaine with an estimated street value of $75,000.

“We disrupted a large-scale operation,” then-U.S. Attorney Philip Hogen told reporters. “We believe this was not the only incident.”’

Sands was placed in pretrial detention at the Glory House in Sioux Falls but was caught drinking at a job site. It was part of an attitude that found him “blaming everyone else for my problems, which is what addicts do,” he said.

Johnson, a Glory House counselor at the time, said Sands’ actions made it clear that he was not ready to accept responsibility and receive treatment for his alcohol and drug abuse.

“When the federal government says you’re in pretrial, you probably need to mind your Ps and Qs at that point,” said Johnson. “Greg was led out of the facility in shackles, and then I didn’t hear from him for quite a while.”

Prison term 'buckled my knees'

After pleading guilty, Sands and his lawyer expected him to get somewhere between 37 and 46 months, based on sentencing guidelines.

At the September 1989 sentencing hearing in Aberdeen, U.S. District Judge Richard Battie characterized Sands as the “organizer” of the drug ring and observed a lack of remorse. There was also concern over Sands’ failure to reveal the identity of his supplier or the number of previous drug shipments.

When Battie asked him prior to sentencing how many times he brought cocaine into South Dakota, Sands replied, “I can’t answer that.”

“Do you wish not to answer, or do you know how many times?” asked the judge.

“I know how many,” said Sands.

“And you wish not to answer. Was it more than once?”

“Yes, sir.”

Moments later, Battie handed down the sentence of 10 years in a federal correctional facility, plus five years of supervised release. Sands felt the world collapsing beneath him.

“It buckled my knees,” he said. “When you hear that, it feels like you’re going to prison for the rest of your life.”

Appeal leads to shorter sentence

By the time U.S. marshals took Sands to the airport a few months later to fly Con Air to federal prison, the Upper Midwest winter had arrived.

“We had on our bus clothes – khaki T-shirt and thin sweatpants, a pair of socks and slippers,” he said. “They take you in a van to the tarmac and there are officers there to search you out in the cold. They give you a bologna sandwich and a piece of fruit and stale potato chips and you’re chained up as they fly all over the country, dropping off and picking up inmates.”

That night was Sands’ memorable encounter at the Oklahoma prison, where inmates were processed for their destination. He served most of his time at Fort Worth and Texarkana facilities in Texas, making connections and continuing to smoke pot while surviving on commissary funds sent from his mother.

His lawyer filed an appeal that was ultimately successful. The Eighth Circuit U.S. Court of Appeals ruled in July 1990 that the district judge erred in denying a reduced sentence based on Sands accepting responsibility for his crimes.

His prison stay was reduced to 24 months, which Sands realized was not a lifetime after all. He began making plans to “get off paper” by satisfying his probation and beginning the process of putting his life back together.

Committed to making a change

Part of that meant writing a letter to Johnson at the Glory House, apologizing for his behavior and asking to be accepted as a halfway house resident upon his release from prison. It was either that or the Brown County Jail in Aberdeen.

The answer was not what he expected.

“I told him no,” recalled Johnson. “I think that surprised him because he was accustomed to using his charisma to get his way and manipulate people, which is not uncommon for addicts. We had a good relationship, but I told him, ‘I’m not sure if I want you back or not. What are you going to do to make changes?’”

As his release date approached, Sands was no longer using drugs and experienced more clarity about his circumstances. He acknowledged that his arrest and incarceration were the result of his own addictive behavior.

“For a while I had blamed the guy in L.A., you know, like I was a victim and he was an idiot,” Sands said. “And then I had an epiphany that my life was screwed up because I was an adult involved in a criminal conspiracy, and I had an addiction that I needed to get my arms around.”

He expressed some of those sentiments in a second letter to Johnson, and this time he got the response that he desired.

“I pretty much knew I was going to take him back,” said Johnson, who retired as Glory House president in 2021. “But I wanted him to really think about it and process it because I wanted him to make a commitment internally that it was time to make a change.”

When his prison release came and he was shuttled to the airport for his flight to South Dakota, Sands headed straight to the airport bar and wrestled with his conscience for a few moments before ordering a Diet Coke.

Love blossoms at AA meetings

It was a few months later in 1991 that Pam Blomstrom first encountered her future husband at an Alcoholics Anonymous meeting.

Pam, who grew up in Hot Springs and started drinking at age 14, moved to Sioux Falls in 1989 after seven years in the Army, an experience that fueled her alcoholism.

“It was like birds of a feather,” she said of her military stint. “You found the ones who liked to drink a lot, and that’s who you hung out with.”

Greg’s first impression of Pam was that he wanted to sleep with her, having recently been released from prison. Her initial observation of him was, “Who’s that dude with a mullet and his pants pulled up too high?’”

For a while, they shared flashes of eye contact at meetings. Both were still drinking occasionally, and after moving into his own apartment, Greg went on a bender that started at the Gaslight bar in Sioux Falls and ended at the Jesse James Saloon.

The next day, he met with his AA sponsor at JerMel’s diner at 10th Street and Minnesota Avenue to discuss how to get back on track.

Pam was their waitress. She recognized Greg and bristled when he ordered an “extra thick” milkshake because she was busy with other tables.

“I told him the milkshake machine was broken,” she recalls.

Still, a connection was there. So when Greg called her after leaving the restaurant and asked her on a date, she accepted.

Life on the bright side

They had dinner at Minerva’s restaurant a few nights later, and Pam learned that Greg had been in prison. When he told her it was for drugs, she knew it was serious but was relieved that he hadn’t done something worse.

She liked his straightforward manner and the fact that he was motivated to make something of his life. The drinking episode that led to meeting with his sponsor turned out to be his last, kicking off more than three decades of sobriety.

After years of dependency and despair, there was appeal in finding the bright side.

Part of that meant Pam getting sober herself, but progress was slow. She was still sneaking around and closet drinking eight months into their relationship, even after they moved in together. Her deceit made her feel more deflated.

When Pam got a hairstyling job at Cost Cutters, Greg began insisting that she take it seriously and show up without fail. Slowly she emerged from her funk and began to appreciate the domestic routine that they built together, a manifestation of love.

“Things were getting better,” said Pam. “I saw the other side. It was something I wanted.”

'We made a great team'

Greg began sharing his addiction and prison experience with others, one of the goals he set while still behind bars.

He helped form a Narcotics Anonymous chapter in Sioux Falls that started with a handful of members with sporadic sessions and grew into a thriving fellowship that now offers meetings every day.

Though Phyllis Sands never got to see her son as a business owner, she did experience Greg's sobriety before she died in September 1993. One of her final entreaties was that he should marry Pam, a request that he took to heart.

They tied the knot in 1995 in Las Vegas, staying at the Tropicana and sharing visions of their future. Greg had gone from folding newspapers at the Shopping News to getting back into drywall, splitting jobs 50-50 with a partner who was content to keep it that way.

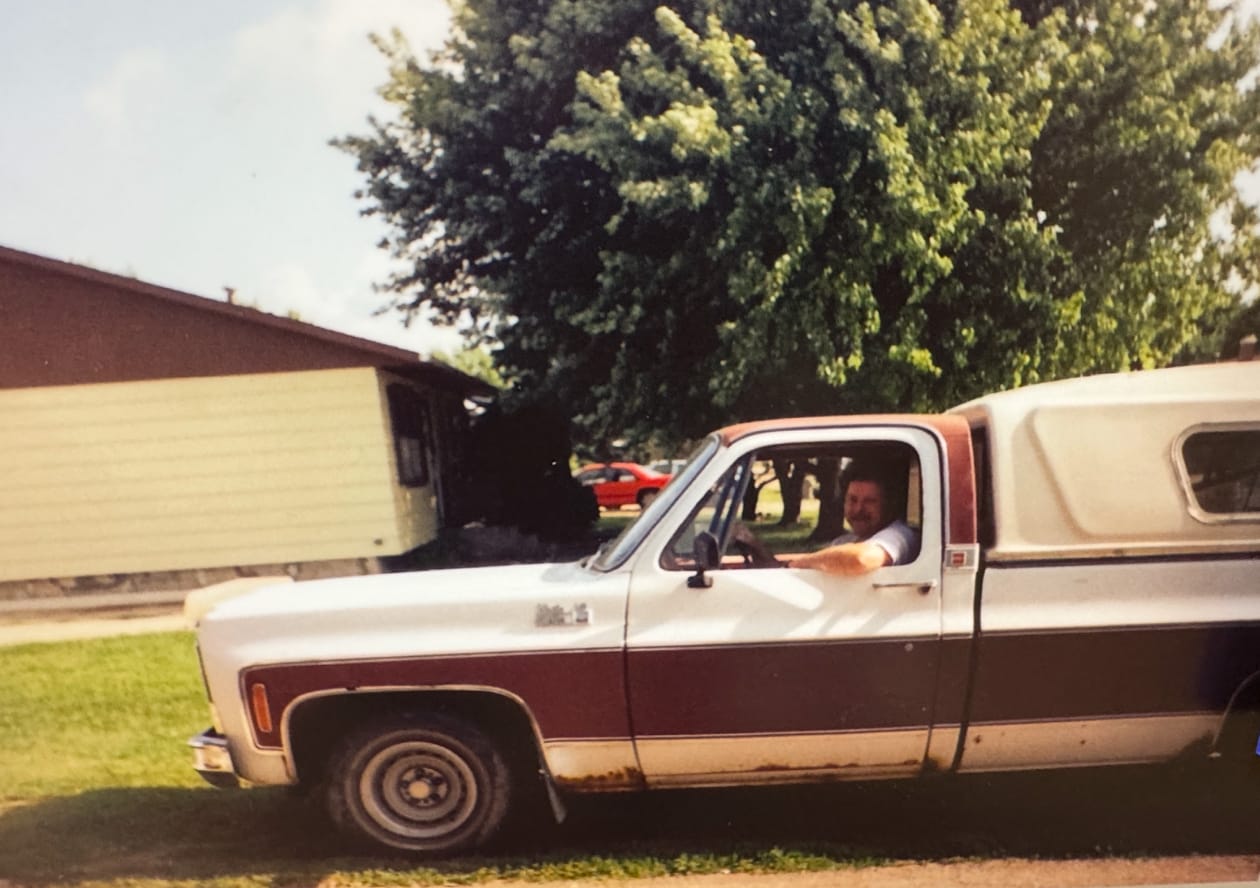

Greg had bigger ideas. He started working out of his 1973 GMC truck but envisioned a day when he would have a crew of five workers with “Sands Drywall” on their uniforms. Pam helped him see it as possible.

“We were tired of our lives sucking, and we made a great team,” said Greg. “Things started to move pretty fast.”

Pavilion job sparks momentum

A major breakthrough came when contractor Gerald Johnson hired Sands to handle taping and drywall finishing on the $32 million Washington Pavilion renovation project in downtown Sioux Falls.

“I walked out of there with 20 good tapers,” said Sands, referring to the process of bonding drywall panels with a smooth surface at the seams. “I went around to all the drywallers in town and said, ‘I’ll come in with my guys and I’ll do a whole floor in a week, instead of your three guys taking six weeks.' Jobs started adding up."

One of his first full-time employees was Terry Curl, who started in 1998 and thought he had blown his chance when he was pulled over in a company truck and arrested for speeding and marijuana possession.

“They pulled me over and patted us down, and I had 2 ounces of pot and alcohol in the truck,” recalled Curl. “They put everything on the hood when they arrested us, so everyone driving by on Cliff Avenue saw Sands Drywall on the truck.”

Sands not only retained Curl but made sure he had a job site to go to for work release as part of his sentence. Last year, Curl celebrated his 25th year with the company, calling Sands a father figure who helped him get sober.

“When it came to drugs and alcohol, I had walked the walk," said Sands. "I knew it was a disease, not a moral deficiency. So I treated it as such, and guys would get a second or third chance, as long as they weren’t at risk of hurting themselves or a co-worker, or losing us a customer. And they had to show up in the morning.”

Looking ahead to the next job

Showing up with a capable crew became a calling card for the company. It was noticed by Sioux Falls general contractor Craig Lloyd, who was in the process of turning Lloyd Companies into a regional powerhouse in real estate development.

First Sands had to prove himself to Al Stone, Lloyd’s construction manager, who hired him for a restaurant project in 2001 and was considering him for other jobs.

“I’d see this guy Greg Sands in my office park every two days, and Al was always beating him up about price,” recalled Lloyd. “One day I poked my head in and said, ‘Al, you've been beating up on this guy long enough. Just give him the job.’ It’s tough dealing with subcontractors, but Greg would show up on time, give us a fair price, and he would work ungodly hours to meet projections.”

The relationship with Lloyd Companies led to Sands Drywall working on the CNA Surety building and Hilton Garden Inn in downtown Sioux Falls; the Pentagon and other projects at the Sanford Sports Complex; and the Grand Falls Casino near Larchwood, Iowa.

By the time Ryan Rademacher came from Minnesota to interview with Greg in 2004 as an estimator, the company had settled into its industrial park location in Tea. In the works was the company’s steel stud and framing division, which would alleviate supply chain problems and allow Sands to expand his reach.

“We talked about the job, and my kids were young at the time,” said Rademacher. “It meant moving our family, so I said, ‘I’ll need to go home and talk to my wife about it.’ This was on a Friday, and Greg said, ‘OK, I’ll give you until Monday.’ He knew what he wanted.”

More than two decades later, Rademacher serves as president on a leadership team that includes president of operations Jared Swenson, carrying out the tradition of always looking for the next opportunity.

“This business grew because of relationships that Greg developed and nurtured over the years,” said Rademacher. “His philosophy early on was that he was always looking for the next job. It was basically, ‘Thank you for this one, but what do I need to do to get the next one?’”

Presidential pardon comes through

While Sands had made amends for his past, the felony conviction prevented him from voting or owning a firearm for hunting. It also complicated security clearances, keeping him from entering federal prisons to speak with inmates about his experiences.

So in the late stages of Clinton's final White House term in 2000, Sands applied for a presidential pardon through his probation office.

“I filled out the forms and sent them in and we waited,” said Sands. “Six weeks before the end of (Clinton's) term, I ran into a probation officer at a coffee shop and said, ‘Could you check on my pardon?’ She checked with the Board of Pardons and they said it wasn't there, so we figured it was going to be denied.”

Pam was working in the Sands Drywall office on Jan. 23, 2001, when a call arrived for Greg. It was an Associated Press reporter seeking comment on the fact that Sands was one of 140 people who had received pardons from Clinton as the president left the White House.

“Every day is a blessing," Sands told the media that day. "I'm a responsible, productive member of society, and that means something."

Taking giving to new level

For Sands, receiving the government's ultimate form of forgiveness brought clarity to his mission. It made him more determined to help others.

He and Pam established a foundation that played a major role in creating the Sands Freedom Center, a residential treatment facility at the Glory House for women just released from prison.

They teamed with regional health systems Sanford Health, Avera Health and the Mayo Clinic to promote addiction treatment while also helping to open the Link, a mental health triage center in Sioux Falls.

Greg and Pam also teamed with Feeding South Dakota to start a tradition of handing out Thanksgiving meals for families in need, with 3,000 turkey meals distributed each year in Sioux Falls and Rapid City.

These efforts were just as instrumental as Sands' business achievements in getting him inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in October of 2024, where he talked about the power of second chances.

While he is not sheepish about touting such accomplishments, his wife is equally open about bringing him back to earth.

One day driving around town, Greg felt compelled to say, "This side of the car is for people that got a presidential pardon."

"This side," Pam responded, "is for people that didn't need one."

Success and responsibility

The day before the company Christmas party in December, Sands spent time at the newly opened Steel District development on the banks of the Big Sioux River in downtown Sioux Falls.

His company had a stake in the project at the urging of Lloyd, whose company bought the land and spearheaded the effort, part of an overhaul of the downtown riverway stretching to Falls Park. Lloyd passed away on Jan. 29.

On the day in December, Sands and Lloyd reminisced before having lunch at the complex, which includes a hotel, residential lofts, restaurants and office space.

They marveled at the growth of the city and their own fortunes, with Sands going from working out of his pickup truck to partnering on some of the city’s most high-dollar deals.

“Some businesses don’t grow with scale,” said Lloyd. “Greg got into steel studs and production and finding a better way to do things, and that helped catapult us into what we do today, which are pretty large projects. This (Steel District) development is about $250 million. I didn’t know there was that much money in the world when I started.”

With success, said Lloyd, comes an elevated sense of community responsibility. His example inspired Sands to lock philanthropy into his company's employee ownership deal, requiring from 2.5% to 5% of profits each year be donated to nonprofits helping with addiction, mental health and hunger.

"It's in our company's DNA," said Sands. "Until the end of time."

Lloyd recalled in 2005 when he and his wife met Greg and Pam to pitch them on sponsoring a Christmas lights display at Yankton Trail Park to benefit the Heartland House, a program to assist homeless families and children.

“We’re in their living room talking and showing them the different displays,” said Lloyd. “And then we start talking about the Heartland House and the homeless people and how much of a need there is, and I look up and Greg and Pam are crying. I was like, ‘Oh, no, what did I say?’ And they said, “No, it’s just that we wish you guys had been here five or 10 years ago."

The clock is ticking, after all. There are only so many days to atone for past mistakes and deliver on promises made when the darkness arrived, allowing for a sliver of light.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email every few days to get stories as soon as they're published. Contact Stu Whitney at stu.whitney@sdnewswatch.org