Editor’s note: This article was produced through a partnership between South Dakota News Watch and the Solutions Journalism Network, a national non-profit group that supports rigorous journalism about responses to problems. This is the final segment of a two-part look at the education of Native American children in South Dakota amid the ongoing COVD-19 pandemic.

A South Dakota Native American tribe has solved one of the biggest challenges facing tribal schools amid the deadly COVID-19 pandemic by developing a plan to provide computers and cost-effective, high-speed internet connections to all students and teachers.

As the pandemic rages on, schools that serve Native communities have been closed and students are being taught remotely, a concept that has forced tribal governments to grapple with the longstanding, expensive problem of providing computers and connecting tribal members to high-speed internet service.

Reaching and teaching children through remote education is nearly impossible if students and their teachers do not have computers or reliable internet service.

Leaders with the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe in central South Dakota say they have found a low-cost solution to the tribe’s computer and internet needs that will aid education but which may ultimately improve life overall in the community.

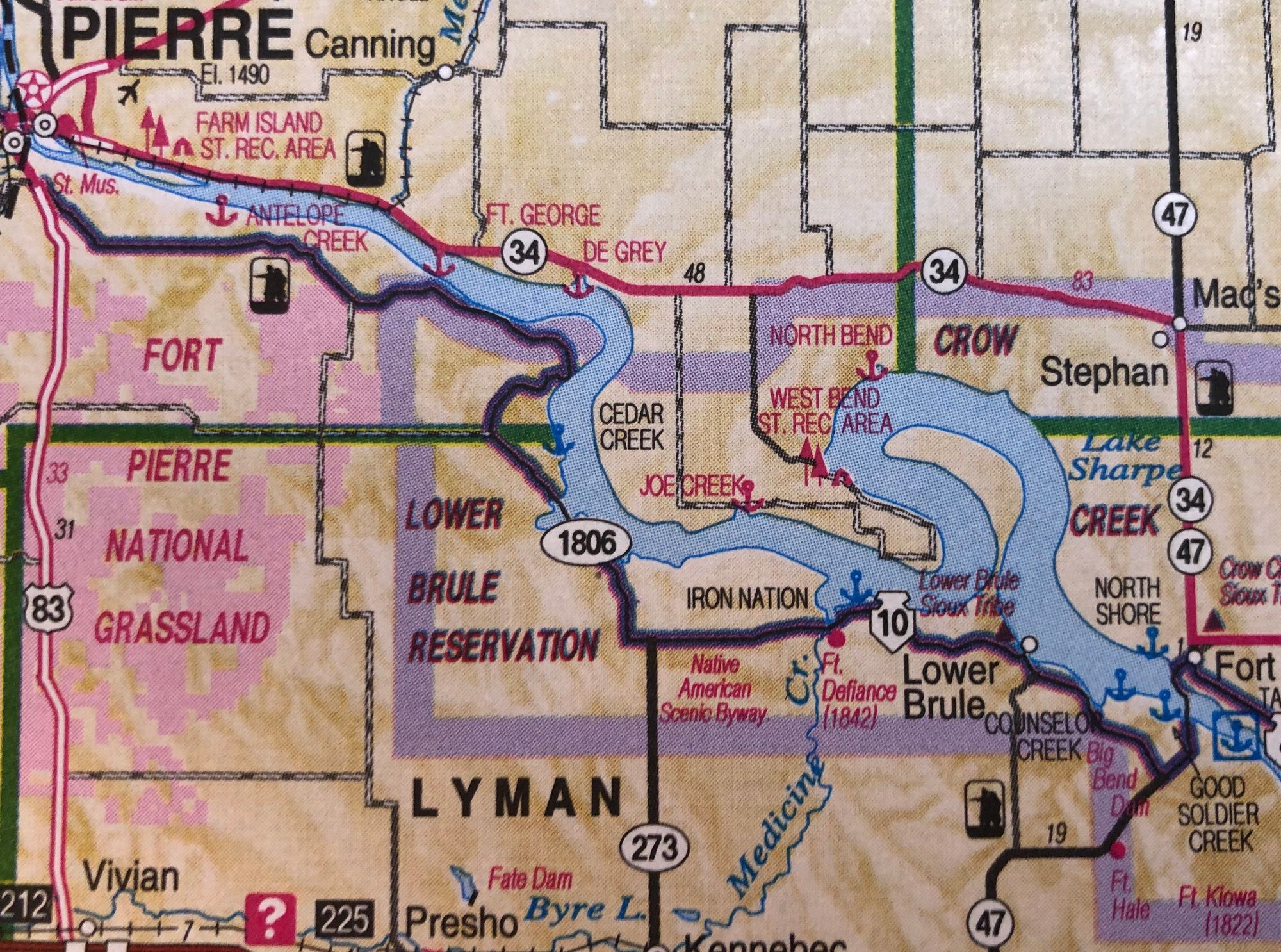

Since early June, the tribe has been working on an ambitious plan to build its own wireless internet network. The idea is to broadcast a high-speed, wireless internet signal across the roughly 207-square-mile Lower Brule reservation using digital radio waves, similar to how cell phones communicate with one another. The tribe’s new network became the first-of-its-kind in South Dakota when it began limited operations at the end of July on the reservation located just west of the Missouri River southeast of Pierre.

Securing adequate internet access for educators and students, not to mention businesses or individual tribal members who want to use the internet, has been a challenge on Native American reservations for years.

But a combination of new technology, the efforts of a California non-profit organization, an influx of federal CARES Act funding and a little luck came together at just the right moment for the Lower Brule tribe, said former Tribal Chairman Boyd Gourneau, who left office in early October.

Gourneau said he met an executive with an organization called MuralNet by chance at a conference for tribal chairmen before the COVID-19 pandemic began. MuralNet was founded in 2017 specifically to help tribal governments exert sovereignty over their peoples’ internet access. Gourneau didn’t know it at the time, but his chance meeting actually put the Lower Brule Tribe in a unique position to eventually build its wireless internet network.

Many of South Dakota’s reservations have closed themselves off to outside visitors and taken other drastic measures to protect their vulnerable populations. Some tribal governments have imposed curfews and restricted or banned social gatherings; at least one tribe is contacting every tribal elder daily to see to their needs.

Geographic isolation and a history of poverty on reservations have led in part to high rates of chronic diseases, including diabetes, heart disease and liver disease. A severe shortage of accessible, quality healthcare has created challenges in the fight for wellness, particularly during the pandemic. As of Sept. 28, Native Americans accounted for 19% of South Dakota’s COVID-19-related deaths and 12% of the state’s overall COVID-19 cases despite making up only 9% of the state population. Reservation economies, which already lagged behind the state as a whole, have been devastated by pandemic-control efforts.

To further reduce the spread of COVID-19, most schools serving South Dakota Native American reservations chose to delay the start of the school year and teach remotely via computers and the internet for at least the first few weeks of the school year.

But large swaths of the state’s nine reservations lack adequate internet access, largely because the reservations are isolated and their populations are spread thin over relatively large areas. The Oglala Lakota County School District, which covers most of the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in southwest South Dakota, for example, covers roughly 2,000 square miles.

South Dakota reservations are also some of the most economically disadvantaged communities in the country. The average household income on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in south central South Dakota is just $22,587, for example. Statewide, the average household brings in more than $56,000 per year and nationally, the average household makes more than $68,000, according to the U.S. Census Bureau.

For service providers, providing high-speed internet infrastructure across rural South Dakota and reservation lands has not been seen as commercially viable. Building a network of fiber optic cables can cost millions of dollars and take years to complete. Such big investments aren’t likely a profitable bet for private companies if there are relatively few customers around.

The Lower Brule Sioux Tribe wireless network has been put into operation for around $250,000, Gourneau said.

And unlike the Verizon and AT&T hotspots many other tribes have purchased for their students, Lower Brule’s network is both permanent and wholly owned by the tribe itself.

The tribe no longer will have to rely on an outside entity to provide its people with what has become an essential tool for economic development, education and overall quality of life, Gourneau said.

“Everything we’re doing is all with the vision of being self-sufficient and not depending on the government,” Gourneau said.

Teaching challenges spur innovation

As in many of the nation’s Indian reservations, internet access on the mostly rural Lower Brule Sioux Reservation was inadequate in mid-March, when schools in South Dakota started to shut down due to the pandemic. Lower Brule Schools Superintendent Lance Witte said many of his school’s roughly 300 students didn’t have any internet access at home.

Some Lower Brule students obtained internet access by using a relative’s smartphone hotspot feature for watching class video and participating in virtual classroom discussions, a potentially expensive prospect not available to many students, Witte said.

“We did not have a one-to-one device program for our students. So trying to do things like Google Classroom or or Zoom meetings and things like that just weren’t in the cards,” he said.

Lower Brule School students finished the 2019-20 school year completing packets of worksheets and other printed school materials that were either picked up from the school or delivered to their homes on a regular basis, Witte said. Lower Brule School’s teachers and students needed a better system, Witte said.

“We realized one of the big things we needed to do is figure out in our community, our rural community out here, we need to figure out how we’re going to get students access to WiFi,” Witte said.

Lower Brule School is a Tribal Grant School, meaning it is funded by federal grants but is controlled by the tribe instead of the federal Bureau of Indian Education, and the Lower Brule Tribal Council serves as the school board. The arrangement turned out to be a big help as the tribe worked to solve the internet access problem for the school’s students because the tribal council was familiar with the needs of the Lower Brule School.

Witte said the tribe took a two-pronged approach to its internet problem. The first task was to put computers or iPads in the hands of all students. Money for that project came from the BIE and resulted in each of the Lower Brule School’s 300 or so students being assigned their own iPad or Chromebook computer to use at home.

"We realized one of the big things we needed to do is figure out in our community, our rural community out here, we need to figure out how we're going to get students access to WiFi." -- Lance Witte, superintendent of Lower Brule schools

But even after making sure each student had a computer, the tribe still needed to get its students connected to the internet. The solution had its roots in a 2019 Federal Communications Commission decision. The ruling allowed for the auctioning of leases for a lightly used portion of the radio wave spectrum, the 2.5 gigahertz band, to commercial users. Tribal governments, though, were given first crack at claiming unused portions of the 2.5 GHz band for use on their reservations.

The FCC regulates who can broadcast signals through the nation’s airwaves to prevent interference in critical communications systems. Periodically, the FCC auctions exclusive rights to portions of the radio wave spectrum. The rights to each piece of the spectrum are assigned via a broadcast license.

The 2.5 GHz band hasn’t come up for auction since the late 1990s and happens to be an ideal candidate for use in broadcasting an internet signal. The band can be broadcast with enough power to penetrate obstacles such as tree leaves and walls, so anyone using the network will just need a simple router to obtain access.

The FCC plan was to allow tribes to submit applications for licenses to use the 2.5 GHz spectrum between Feb. 2, 2020 and Sept. 2, 2020. By the end of Sept. 2, tribal governments had submitted 349 individual applications for 2.5 GHz spectrum broadcast licenses on their reservations. On Sept. 15, the FCC announced that it had accepted 157 applications. The Lower Brule Sioux Tribe, was one of the first tribal governments in the U.S. to take advantage of the 2.5 GHz spectrum.

“It’s like the tribe claiming the air, which is afforded to us by the FCC, much like we would claim our mineral rights,” said Witte.

Nonprofit tech firm helped set up network

In June, the Lower Brule Tribal Council partnered with a Silicon Valley nonprofit called MuralNet to plan and build its wireless internet network. The tribe’s goal was to broadcast a high-speed internet signal to each home on the reservation by the time school started on Sept. 8.

To meet its goal, the tribe applied for a temporary broadcast license so it could broadcast its internet signal before receiving the official FCC license.

MuralNet was founded in 2017 specifically to help Native American tribal governments exert sovereignty over their tribal internet connections. With the nonprofit’s help, the Lower Brule Tribe applied for and received a temporary permit to broadcast an internet signal using the 2.5 GHz spectrum.

The tribe, with MuralNet’s help, negotiated to buy a large, commercial internet connection that could be broadcast and shared among the network’s users. MuralNet, which has a partnership with the tech conglomerate Cisco Systems to build wireless networks for tribes, then helped the tribe set up antennas on their municipal water tower to broadcast a wireless signal that gives anyone with the right router immediate access to the internet through the tribe’s fiber optic line.

Essentially, the Lower Brule tribe built its own cellular network, said Mariel Triggs, MuralNet’s CEO.

“They’re passing out their own hotspots, so there are no subscription fees,” Triggs said. “They have control over it, they get to maintain it and all they have to do is pay for the connection to the internet pipe for the whole system.”

Owning its own network means the tribe can buy internet access at less expensive wholesale prices and can control what its people pay for in-home internet access.

Broadcasting a high-speed internet connection, as opposed to running fiber optic cable to each house, means the tribe’s network will cost a fraction of a traditional hard-line network. A small tribal community in Arizona’s Grand Canyon, for example, was able to provide internet connections for all of its residents through a similar venture for about $15,000 in 2017.

Laying fiber optic cables to connect rural homes to the internet can cost between $16,000 and $60,000 per mile, according to a 2019 report by the South Dakota Governor’s Office of Economic Development.

A wireless network also takes far less time to build. From start to finish, the Lower Brule Tribe network only took about two months to get up and running, Triggs said. The tribe first met with MuralNet on June 1 and its network was broadcasting by the end of July.

“Lower Brule is actually our record right now,” Triggs said. “And they’re already in the process of expanding their network so that they can add on more students.”

As of Sept. 29, there were 25 Lower Brule households accessing the tribe’s network, Gourneau said.

Because wireless internet technology is so much more affordable, virtually any tribe who wants to try setting up its own network can, Triggs said. While the Lower Brule Tribe was able to secure a federal license for exclusive use of the 2.5GhZ band of radio wave spectrum, there are other spectrum bands that don’t require licenses to use. MuralNet’s partnership Cisco Systems can even help pay for some of a network’s planning and setup costs.

Still, broadcasting an internet signal comes with some inherent problems. For one thing, the signal requires a line of sight to each home trying to access it. A house whose line-of-sight to the tribe’s antenna is blocked by a hill won’t be able to connect, Triggs said. The signal also doesn’t yet have enough range to reach every corner of the reservation.

There are workarounds for the network’s limitations, Triggs said. One workaround to the lack of range would use parabolic microwave antennas to shoot a powerful, narrow beam of signal to far flung communities on the reservation. A weaker signal could then be broadcast from an antenna on a telephone pole to nearby homes.

Another option would be to run a fiber optic cable out to a reservation community, attach an antenna to it and broadcast a signal from there. But running fiber optic cables is an expensive prospect.

Right now, the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe is paying for its internet connection using money from the CARES Act, the federal coronavirus relief package. The tribe’s next big challenge will be figuring out how to make the new network sustainable, Triggs said. Normally, a sustainability plan would have been one of the first things MuralNet helped the tribe with, but that step was skipped to get students connected to the internet more quickly amid the pandemic.

For the immediate future, the tribe will remain focused on ensuring its students have immediate and ongoing internet access, said new Lower Brule Tribal Chairman Clyde Estes, who became chairman in October.

The potential long-term economic benefits to the entire community could be huge if a fast, reliable internet service can be implemented and maintained, he said.

“I think we’re really ahead of the game,” Estes said. “I believe it will be a great thing because there are a lot of people that need to do business online. Maybe we can teach adults and elders who have never done internet stuff before how they could access their financial information or keep up with current news and events going on.”