A series of juvenile justice reforms enacted in South Dakota over the past decade has kept more low-level youth offenders out of detention centers and away from criminal activity that could land them in the adult system, according to state officials.

But state data show that youth of color — who make up a wide majority of the population in the juvenile justice system — have not benefited as much from the reforms and are still being detained in locked facilities at much higher rates than white youths.

In the early 2010s, South Dakota placed children in a detention center after an arrest at a higher per-capita rate than any other state in the country, and almost half of the youth offenders who spent time in a detention facility ended up in the criminal justice system.

At the time, there were very few options outside of locked detention centers for youth involved in the justice system in South Dakota, which contributed to high youth incarceration populations, according to a report by the state Juvenile Justice Oversight Council.

In many situations, putting children in a detention center was the only way for them to get help, and low-offending minors often mixed with youths accused of more severe offenses.

That prompted lawmakers, judges, attorneys and advocates to consider whether committing children to a correctional facility was the best way to respond to juvenile crime, laying the groundwork for a set of reforms passed in 2015 aimed at decreasing the number of youth who are put in detention for low-level offenses, increasing youth court attendance and lowering recidivism.

The reforms didn’t necessarily result in fewer youth committing felony crimes, but they did raise the threshold for when youths are placed in detention, and increased the number allowed to enroll in community-based diversion programs.

A major goal of the reforms has been to keep children who are accused of misdemeanors or low-level felonies out of locked detention centers where they lose contact with family and community, and where instead they come in close contact with youths who committed more significant crimes, some of which are serious enough to be handled in adult court.

“We’re attempting to minimize the effects of labeling youth as offenders,” said Annie Brokenleg, coordinator of the state Juvenile Detention Alternatives Initiative, which encompasses the state reform efforts. “The farther a kid is processed through the system, the higher their chance of offending in the future.”

Since JDAI was enacted, more children are being put into diversion programs within local communities rather than being sent to a locked detention facility potentially hours away from their home. The reforms aim to keep low-level offenders out of locked facilities while awaiting trial and also reduce the number of youths who are convicted and sent to secure facilities to serve their sentence.

Since 2011, admissions into youth detention centers have decreased by 81% in Minnehaha County and by 64% in Pennington County, the state’s two population centers.

Reforms less effective for youth of color or with mental issues

But major challenges remain, especially among Native Americans, other minority populations and emotionally troubled youths who enter the justice system at disproportionately high rates in South Dakota. Juvenile justice officials say the state needs more treatment options for youth with mental health needs and more cultural-specific programs for youth of color.

Data from the Juvenile Justice Oversight Council and Kids Count identified an increasing over-representation of Native American youths and Black youths in the juvenile system over the past decade.

The number of youth of color admitted to a detention center has decreased overall, but the proportion of youth of color who are detained in locked facilities is still disproportionate compared to white youth.

In 2014, counties with the juvenile justice reforms in place reported that 75% of the youth admitted to a detention facility while their case worked through court were youth of color, according to Kids Count. In 2020, the proportion of youth of color admitted to facilities from those same counties had increased to 81%.

In 2011, Native American youth were 23% of the state youth population, but Native youth made up 45% of those put into temporary custody and 48% of the new commitments to the Department of Corrections, according to a 2015 state report.

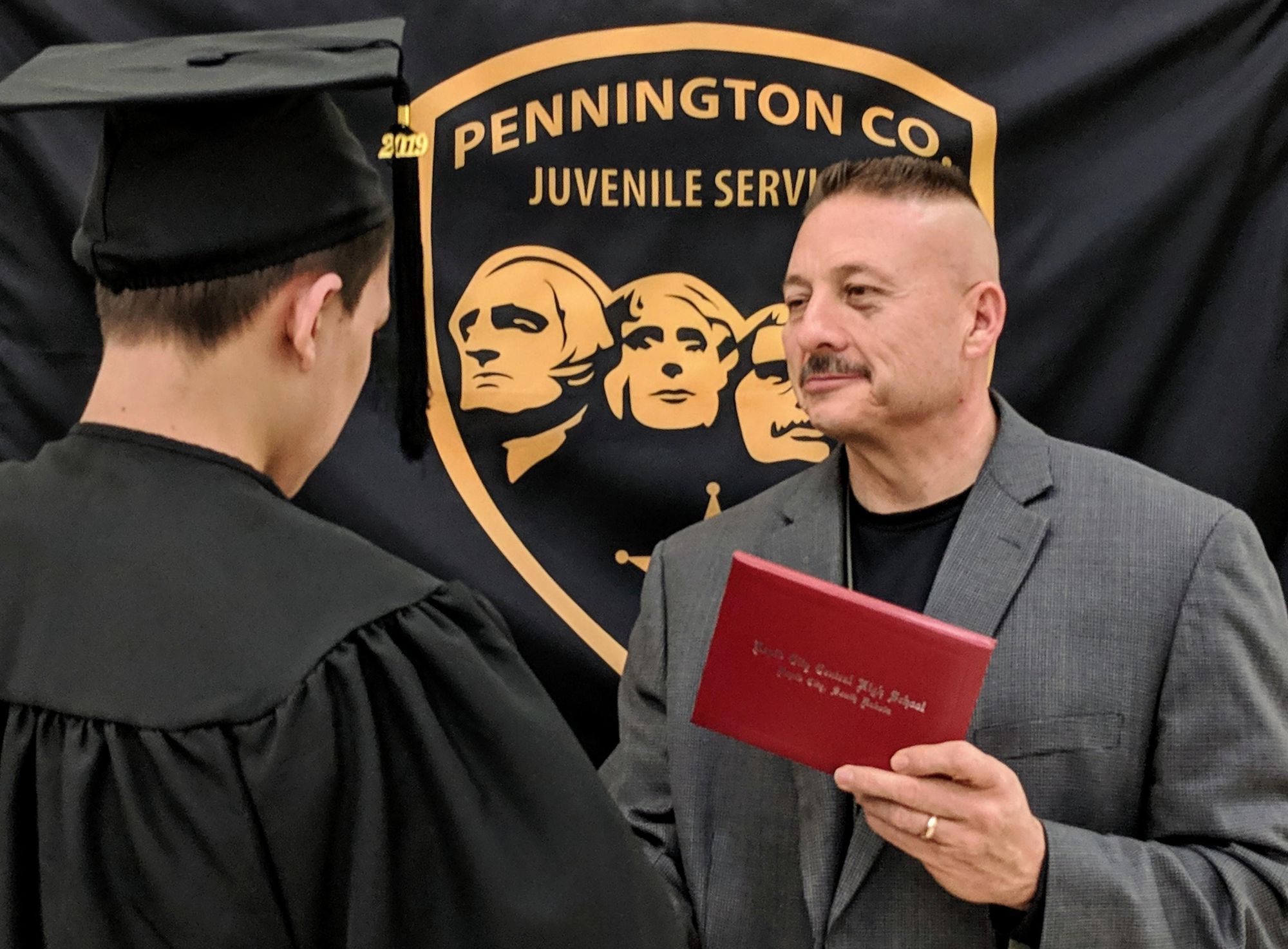

Now, about 60% of the youth in the locked juvenile services center in Rapid City are Native American, said Joe Guttierez, Pennington County Juvenile Services Center Commander.

Overall, about 81% of the youth admitted to that detention center in 2020 were youth of color, according to data from Kids Count. Those numbers also include kids working through the federal system. In Minnehaha County, 68% of youth admitted into a detention facility last year were youth of color, compared to 61% in 2011.

Discovering and implementing programs to reach more youth offenders of color is the next step but also one of the most challenging hurdles to overcome in the ongoing efforts to reform juvenile justice in South Dakota, said Brokenleg.

New efforts are being made to expand culturally sensitive programs to reach more youths, and to increase access to services for children in rural areas, she said.

“We’re working on culturally responsive programming to improve outcomes for youth of color entering the system,” Brokenleg said.

Juvenile justice reforms that are keeping more South Dakota youthful offenders out of locked facilities have had some unexpected negative outcomes. Putting fewer youths in detention has put more responsibility on families, law enforcement and schools to manage youths who are repeatedly disruptive but whose behaviors do not warrant incarceration.

School expulsions were on the decline until last year, when they more than doubled from the year prior. The 33 students expelled from schools statewide from July 2019 to July 2020 was the highest number of expulsions since 2016, when 22 students were expelled.

Law enforcement agencies sometimes see the same child over and over again and can’t put them in detention because of a suggestion based on the risk assessment tool.

Families frustrated by ongoing teen misbehavior sometimes want their child to be taken to a detention center in hopes of changing their behavior, but may be unable to do so under the reformed system, said Davison County Juvenile Diversion Director Katie Buschbach.

“I think a lot of it is everybody is trying to see what everybody else can do,” Buschbach said. “We’ve all been kids before. It takes time. It takes time for these kids to learn these things. We’re going to get through it.”

Directors of the state’s two largest juvenile detention centers, in Minnehaha and Pennington counties, said the biggest challenge they face is a lack of access to long-term mental health services.

“We have kids with mental health issues but have committed an offense. Because they have mental health issues, they’re hard to place, and there are not a lot of places for kids with mental health concerns,” said Guttierez in Rapid City.

According to a provisional 2020 report from the Juvenile Justice Oversight Council, mental health services are available statewide, but it’s unknown how long those options can serve a child. The Human Services Center in Yankton is the only state-run behavioral center and has limited space for minors.

In Minnehaha County, Juvenile Detention Center Director Jamie Gravett said the reforms already in place would be enhanced by increasing long-term mental health services for juveniles.

“We need to come up with a better solution for mental health problems,” Gravett said. “They work hard in the community, but there comes a time when only so much can be done in the community.”

Gravett and Guttierez also said they are seeing younger children get involved in crime and substance use, particularly abuse of alcohol, making the need for diversion programs even greater. Overall in 2020, about 3,700 youths were arrested for a crime in South Dakota.

Over the last few years, citations for alcohol use have increased, while all other kinds of citations, including truancy, damage to property and petty theft, have decreased.

Alcohol citations for youth have increased from 37% of all citations given in 2016 to 66% in 2020. Cannabis youth treatment and cognitive behavioral treatment for substance abuse were added to juvenile services in 2019. Since then, 108 youth have been served one of those treatment options.

Several reforms seen as a success

The pilot juvenile alternatives initiative was introduced in Pennington and Minnehaha counties in 2011 and then expanded statewide four years later alongside a cluster of changes brought with the Juvenile Justice Public Safety Improvement Act approved by the Legislature in 2015.

As part of that legislation, services such as functional family therapy, substance use disorder treatment and aggression replacement treatment were made available statewide.

“We have seen a drastic reduction in detention admissions (while maintaining public safety) across the state and local jurisdictions have been able to reallocate detention dollars to more successful alternatives like evening reporting centers, shelter care, and community supervision,” Greg Sattizahn, chair of the Juvenile Justice Oversight Council, wrote to News Watch in an email.

Several juvenile diversion programs have seen success over the past decade. About 60% of families who participated in functional family therapy from July 2019 to July 2020 completed the program, and about 90% said they experienced a general positive change in family relationships.

About 64% of youth enrolled in aggression therapy completed the program and 92% of parents say their children reacted positively to the treatment.

Criminal recidivism among youth has been on the decline since the reforms were passed, data show.

The number of youth who do not reoffend within three years of attendance in a probation or diversion program has increased from 65% in 2014 to about 85% last year. Since JDAI was introduced, a larger proportion of youths charged with crimes have completed probation, and fewer have been committed to the Department of Corrections. The cumulative months children have been committed to out-of-state facilities has decreased by about 50% since 2015.

Authorities use a Risk Assessment Instrument, or RAI, to determine where they take a youth who has come into contact with law enforcement. By considering the most recent offense, previous interactions with law enforcement, likelihood to reoffend, home life and other factors, the risk assessment tool suggests whether a juvenile will go home, go to a service center or diversion program, or go to a secure detention facility while their case works through the legal system.

“Diversion is a very developmentally appropriate way in response to most youth misbehavior,” Brokenleg said. “Teens make impulsive decisions and choices. If we can meet them where they’re at, that’s definitely going to produce better outcomes in the long run.”

The risk assessment instrument has been crucial to prevent the intermingling of youth who make one mistake with those who need longer contact with authorities, Guttierez said.

“If you place them in detention with kids who are here for some serious assaults, rape and murders, it’s not wise to put those two people together,” Guttierez said. “If a low-risk kid meets a high-risk kid, they become more high risk than the other way around.”

Since 2015, five more South Dakota counties have adopted the diversion efforts: Brown, Davison, Codington, Brookings, and this year, Yankton.

Buschbach has coordinated programs for about 130 children in diversion since the program started in Davison County in October 2019. She tries to tailor the program to the situation, she said. A successful diversion is when a child goes through their four-month program without reoffending.

“I think we’ve learned that we can rely more heavily on our own communities than we had originally thought,” Buschbach said. “We had to start getting creative with how we were dealing with things rather than sending them to a facility and expecting them to be healed in two weeks from trauma they’ve had for years.”

Overall, she’s pleased by the community members who have gotten involved and created programs to help children locally, and hopes a diverse set of treatment options will help more youth.

In Rapid City, a Native American-centered program called I.Am.Legacy works to bring justice and cultural healing to youth with talking circles in jails, a gym for justice-involved youth and more.

“I wish we had those programs all over the state,” Brokenleg said. “When we say diversion and community programming, my vision is we’re utilizing programs like that.”

In Brookings County, the Boys and Girls Club started a program called 180, where leaders in the community come into the club weekly to meet with youth in the diversion program and teach them new skills or educate them about different career paths, said Karlee Chapin, juvenile diversion director for the club.

In Davison County, Buschbach helps children create and monitor a garden. Those who have attended have enjoyed the programs so much that they have asked to continue attending once they complete diversion, she said.

Both directors say families appreciate being able to keep their kids in the area, rather than sending them away. Some families, however, are frustrated by ongoing behavior and would sometimes prefer to have the child temporarily out of the home, and sometimes that’s appropriate, they said. But the mindset of sending away every child who commits an offense is starting to shift.

“Prior to JDAI, we needed that immediate gratification of locking a kid up. When we didn’t get that, people got upset,” said Gravett, juvenile detention center director in Minnehaha County.

Gravett, who was a probation officer when JDAI came to Minnehaha County in 2011, said he believes the reforms have been mostly effective at creating a better path forward for youth offenders.

“I think overall it’s been very positive. Not everyone will agree with me,” he said. “What people need to understand is just because they don’t get locked up immediately after an arrest doesn’t mean nothing happens. They’re still given consequences through the court. We’re trying to look at what benefits the kids the most. It doesn’t mean they aren’t going to get some form of punishment down the line. The process doesn’t stop just because they’re not locked up.”