One major concern of South Dakotans who opposed legalization of medical and recreational marijuana was that it could lead to an epidemic of youth use of the drug.

Drug-abuse prevention advocates and law enforcement officials said greater availability of marijuana would almost certainly lead to an increase of use among children and teens whose brains are still developing.

Despite their concerns, however, research conducted by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the National Institutes of Health has not found an increase in the regular use of marijuana among youths in Oregon, Washington or Colorado, the states where marijuana legalization has been most extensively studied.

Colorado, for example, has a lower overall youth marijuana use rate than the U.S. as a whole. And in all three states, as in the rest of the U.S., there has been a long-term decline in the regular use of marijuana among youths.

Those statistics provide little comfort, however, for those in South Dakota who are on the front lines of the battle to prevent drug abuse by youth.

Marijuana use is associated with poorer performance in school, increased risk for mental health disorders and other negative behavior outcomes for youth, said Maureen Murray, director of mental health and prevention services at Youth and Family Services in Rapid City.

“It is concerning because legalization makes people think that using marijuana is safe and doesn’t have consequences, and teens don’t need to to hear that,” Murray said. “We have very significant concerns with teens.”

South Dakota voters approved statewide ballots measures on Nov. 3 that have set the stage for legalization of both medicinal and recreational marijuana in July. Marijuana would be legal only for those 21 and over. South Dakota was one of four new states to legalize recreational marijuana on Nov. 3, bringing the total to 15. Medical marijuana will soon be legal in 36 states.

“It is concerning because legalization makes people think that using marijuana is safe and doesn’t have consequences, and teens don’t need to to hear that." – Maureen Murray, Youth and Family Services in Rapid City

Regular marijuana use is defined in surveys as respondents having used the drug at least once during the 30 days before they took the survey. Research has shown that regular and heavy use of marijuana among teens carries the most risk for long-term negative effects.

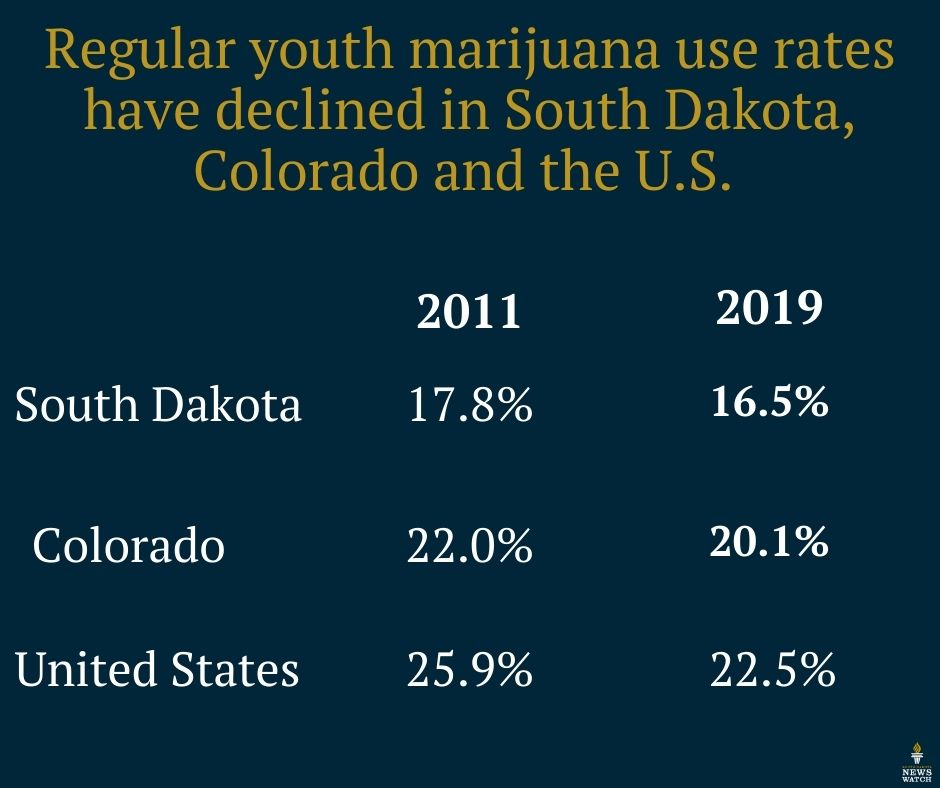

National surveys such as the biennial Youth Risk Behavior Survey have shown small declines in the number of youths regularly using both marijuana and alcohol over the past decade. South Dakota has generally followed the national trend, with surveys showing a decline in regular youth marijuana use from 17.8% of youths surveyed in 2011 compared to only 16.5% in 2019.

Colorado, where recreational marijuana has been legal since 2014, also has seen declines in youth marijuana use. From 2011 to 2019, the youth use rate dropped from 22% in 2011 to 20.1% in 2019. Prevention experts say national and state education programs and prevention efforts have played a big role in declines in youth marijuana use.

Concerns over marijuana legalization among the South Dakota drug-abuse prevention community range from worries over use by motorists to the potential for women to harm children by using marijuana while pregnant or breastfeeding, said Darcy Jensen, executive director of Prairie View Prevention Services. Jensen is a licensed addiction counselor and a leader of the Coalition for a Drug Free South Dakota.

Members of the coalition met Nov. 12 to begin planning a response to marijuana legalization, Jensen said. Though reform was badly needed in how marijuana and other drug use has been treated by the criminal justice system, full legalization of marijuana was not the best way to fix those problems and may lead to new issues, Jensen said.

“I don’t know that this was a place that I would want South Dakota to be in, but we are, so we need to find ways to counter it, and continue to provide positive prevention education,” Jensen said.

Legalizing marijuana causes causes new social and health problems, Jensen said, citing reports from Colorado showing that the number of traffic fatalities in which a driver tested positive for marijuana increased from 18% in 2013 to 32% in 2017.

Meanwhile, the rate of marijuana-related hospitalizations has risen sharply from an average of 1,440 per 100,000 hospitalizations annually from 2010 to 2013 to 3,517 last year. But perhaps most concerning, Jensen said, was that the number of suicide victims found to have marijuana in their bloodstreams increased.

A closer look at Colorado data reveals a nuanced, inconclusive picture of marijuana legalization. In 2018 the state Department of Public Safety published a comprehensive report on impacts of marijuana legalization. The report shows that while Colorado has seen an increase in its number of traffic fatalities, eight states with similar populations and traffic patterns that had not legalized marijuana also saw similar increases in traffic deaths. Pinning the rise in Colorado traffic deaths solely on marijuana legalization was not possible, the report said.

Furthermore, Colorado’s rising number of marijuana-related hospitalizations might have been influenced by changes in how hospitals track diagnoses. The healthcare industry in 2015 updated the diagnosis codes used for billing, creating many new coding categories. More codes meant doctors had more options to indicate whether they believe a patient had been using marijuana prior to being hospitalized, the 2018 Colorado public safety report said.

Suicide rates in Colorado have increased less only slightly, from 19.7% in 2012 to 20.5% in 2016. The rate of Colorado suicide victims testing positive for marijuana has nearly doubled from 11.8% in 2012 to 22.3% in 2016. Nationally, about 22.4% of suicide victims tested positive for marijuana in 2016, data that includes states where marijuana is not legal, according to a 2018 CDC report.

Still, experts studying youth marijuana use and the effects of marijuana on brain development say that South Dakota’s drug-abuse prevention advocates are right to be concerned about legalization. While there does not appear to have been sharp increases in the number of children and teens using marijuana in states that have legalized, legalization remains a relatively new concept and longitudinal studies are few.

Data show increase in adult pot use

Little evidence exists to show that legalizing marijuana for medical purposes causes an increase in youth use of the drug. There also is little evidence, so far, that legalizing marijuana for recreational use leads to an increase in the overall number of children smoking or otherwise ingesting the drug. Instead, research shows adult use typically rises with legalization.

“Once medical cannabis laws or medical marijuana laws are enacted, we usually see increases in use in adults ages 26 and older. But we don’t see any increases in use among adolescents, which is good,” said Dr. Silvia Martins, director of the Substance Use Epidemiology Unit at Columbia University. “Regarding recreational legalization of cannabis, most of the research has shown that increases in use is mainly among adults.”

A September 2019 report from the National Institutes of Health found that Colorado has seen no increase in the number of adolescents using marijuana since legalization for adults 21 and over in 2014. The biennial Youth Risk Behavior Survey found that in 2019, Colorado’s estimated rate of youth marijuana use of 20.1% was lower than the national rate of 21.7%.

An October 2019 report from the CDC found that marijuana use among students in 10th and 12th grades in Washington state did not significantly change from the year 2000 to 2016. For students in 8th grade, the regular marijuana use rate fell by half, from 12% in 2000 to 6% in 2016. In Washington, legal sales of recreational marijuana began in 2014.

Still, researchers such as Martins caution that there has not been enough research into how legalizing recreational use of marijuana affects youth drug use to draw major conclusions.

At most, researchers have only had a few years of data to study, Martins said. Most of the data on population-wide youth marijuana use come from anonymous surveys of students administered in schools such as the Youth Risk Behaviors Survey. States conduct the survey in schools during odd-numbered years, and its results are reported to the CDC. Public health officials use the survey to monitor such things as drug and alcohol abuse among adolescents.

In Colorado, there have only been two Youth Risk Behavior Surveys conducted since legal sales of recreational marijuana began, one in 2017 and one in 2019.

Another potential factor in youth marijuana use is how children growing up watching their parents and other adults use marijuana will view the drug. Parents can have a strong influence on their children’s choices, said Magdalena Cerda, director of the Center for Opioid Epidemiology and Policy at New York University’s Grossman School of Medicine.

“Previous studies have found that if your parents use drugs, then the likelihood of you using drugs is going to be higher,” Cerda said. “Whether that is because you think it is more acceptable, or it is because drugs are more available to you, or because of something else entirely, is relatively unclear. But I would say that is a concern.”

Another 10 years could pass before the normalizing effect of legalizing marijuana shows up in surveys of high school students, she said.

Researchers have identified some troubling trends among youths who regularly use marijuana. A few studies have found increases in Cannabis Use Disorder among youths who regularly use marijuana in states that have legalized recreational sales of the drug, Cerda said. Cannabis Use Disorder is generally diagnosed when someone can’t quit using despite trying, starts having trouble at work or school due to marijuana use, or gives up social activities due to use of marijuana.

“That is obviously a concern because dependence on cannabis actually has an effect on your life, on your interactions with others and on your work,” Cerda said. “Essentially, a cannabis addiction, particularly for adolescents, can have long-term effects.”

Concerns remain over long-range impacts

Marijuana use has been associated with an increase in a person’s risk for developing a mental health disorder, said J. Cobb Scott, an assistant professor of psychology at the University of Pennsylvania Perelman School of Medicine. There also is evidence that using marijuana can lead to psychotic episodes in people who already have schizophrenia. Psychotic episodes can lead to involuntary hospitalization, homelessness or suicide, Scott said.

One significant risk of marijuana use is in youths and young adults who potentially are at risk of schizophrenia or depression, said Scott, who has spent years researching how marijuana use affects brain function and mental health.

But just because someone who has mental illness has a history of marijuana use doesn’t mean the drug caused the illness, Scott said. Researchers have attempted to prove marijuana use causes mental illness but have had mixed results.

A 2019 study of how marijuana use contributed to the prevalence of psychosis in adults in Europe, published in the medical journal The Lancet, found that people using high potency marijuana every day were five times more likely to develop psychosis than people who didn’t use the drug. But a 2016 study of data collected by the National Epidemiological Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions found no link between marijuana use and mental health disorders.

“There’s evidence both ways right now,” Scott said. “And what we don’t have is a lot of epidemiological evidence. We have seen increased use of cannabis over the last 15 years or so, but we don’t have the hugely increased rates of psychosis that you might expect if that relationship were really strongly causal.”

Part of the difficulty in pinning down whether or not marijuana can cause psychosis is that most of the research into how marijuana affects people has been observational. Researchers have essentially had to wait for people to start using the drug on their own before marijuana’s effect on them can be studied. Because researchers are not controlling who uses the drug or how much they’re using, and are often not recording their subjects’ medical histories or IQ levels before they start using marijuana, it can be hard to know for sure the significance of the drug’s impacts.

“We know that the brain continues to develop through the teenage years and into the mid-20s, and we know that any psychoactive substance like cannabis can potentially affect brain development.” -- J. Cobb Scott, University of Pennsylvania

Drawing conclusions from observational research requires large sample sizes being studied over several years, Scott said.

Some of the best evidence of marijuana’s effect on brain development and mental health comes from a study conducted in New Zealand. In the study, researchers followed more than 1,000 people from the age of eight until they turned 38.

The New Zealand researchers found that subjects who developed an addiction to marijuana and began using it heavily before turning 18 and remained addicted to the drug for many years lost an average of six Intelligence Quotient points. People who started using marijuana as adults did not lose any IQ points, the study found.

An ongoing study being conducted by the U.S. National Institutes of Health, called the Adolescent Brain Cognitive Development study, should give scientists a much better understanding of how marijuana affects young brains. The study will follow more 10,000 children aged 9 and 10 for a decade. Researchers will collect information on the children using brain scans, genetic and psychological tests, academic records and surveys. The study began in 2015.

One area where there is strong evidence of marijuana’s effects on people is cognitive function, or how well a person’s brain works. Many studies have shown that frequent cannabis use can impact cognitive functioning in specific areas, including memory and behavior, Scott said. Marijuana’s cognitive effects, though, tend to wear off fairly quickly after someone quits using the drug.

“A couple of larger studies have shown that heavy use starting before the age of 18, and going on pretty consistently for a number of years, may cause long term changes in cognitive functioning. But that is a very small group of people,” Scott said.

Still, South Dakotans should be concerned about marijuana use among teenagers, Scott said. There are too many unknowns about the drug’s effect on brain development. Studies of rats, for example, have shown that marijuana can affect the development of important parts of the brain such as the hippocampus, which plays a significant role in learning and memory.

“We know that the brain continues to develop through the teenage years and into the mid-20s,” Scott said. “And we know that any psychoactive substance like cannabis can potentially affect brain development.”