The very framework of democracy in America is being weakened by the rapid, widespread demise of local news organizations, particularly small newspapers that once served as trusted providers of information and pillars of their communities, according to Margaret Sullivan, who spoke virtually to a South Dakota audience on Tuesday, June 30.

Sullivan is the media columnist for The Washington Post who formerly served as the public editor of the New York Times and as editor of the Buffalo News, her hometown newspaper.

Sullivan is a former member of the Pulitzer Prize board and a director of the American Society of Newspaper Editors, where she led the First Amendment committee. Sullivan has also taught graduate journalism courses at Columbia University and the City University of New York.

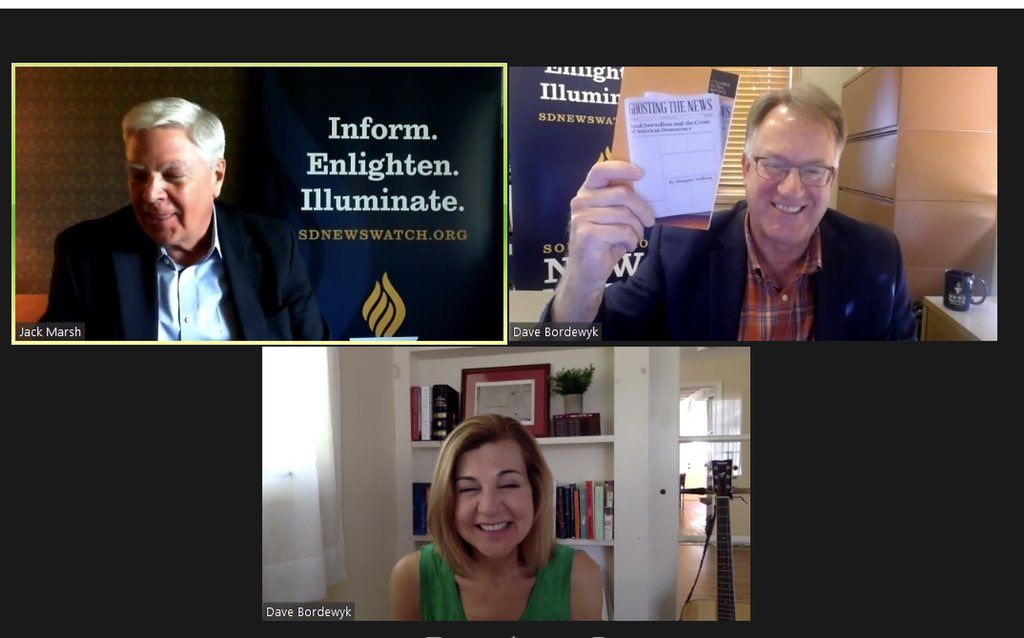

Sullivan spoke during a Zoom webinar sponsored by South Dakota News Watch and moderated by News Watch co-chair and co-founder Jack Marsh.

The News Watch virtual meeting was the informal kick-off of a publicity tour for the forthcoming publication of Sullivan’s book, “Ghosting the News: Local Journalism and the Crisis of American Democracy.”

The book examines the decline of local news in the internet era and the ongoing and potential future implications of losing local news organizations that are a key component of informing the public.

Sullivan noted that about 2,000 of 7,000 U.S. newspapers closed between 2004 and 2015, most of them weekly papers that were the only source of local news in their communities. Many other small papers have become “ghosts” of their former selves, now lacking much of the news-gathering resources and quality of content they once held, she said. In many cases, the closure of news outlets has led to what experts refer to as “news deserts,” or geographic areas where citizens have no source to obtain local news or information.

The news industry, once profitable and stable, has “really been decimated and it’s one thing to say it’s terrible for journalists, but it’s really terrible for citizens who rely on this information to go out and vote … and know what’s going on in their town,” Sullivan said.

The shift of advertising and associated revenues from print to the digital space, changes in the way readers access and consume news, and the newspaper industry’s failure to react to the changing trends have led to layoffs of reporters, a shrinking of the size and depth of news publications and the closure of many outlets, Sullivan said.

The rise of the internet and the public’s subsequent expectation of obtaining news for free is also a contributing factor, she said. Beyond that, the recent COVID-19 pandemic that has led people to stay home and subsequently hurt the bottom lines of many businesses has further reduced advertising revenues for local news organizations.

“It’s not exaggerating to say that local news is in a crisis situation,” she said. “It’s happening and it’s only going in one direction, and many people don’t seem to know.”

The result is that the public is less informed, government officials and the powerful are more able to act without oversight, and communities and democracy as a whole are weakened, Sullivan said.

“Our democracy is built on the idea that the people are going to govern themselves,” Sullivan said. “If they [the public] are not well-informed, the whole thing sort of dwindles away and we can no longer be that movement of, by and for the people that the founders wanted us to be.”

Prior to the Great Recession of 2008, newspapers were contented with strong profit levels, and they were slow to adapt to a shift of news consumption in the digital space, Sullivan said. The news industry also failed to innovate and create models in which people who get news online are required to pay for it — a problem that remains today.

“When you go to the supermarket … you have to pay at check-out for what you bought,” she said. “There’s a feeling that the internet should make things free, and we have to overcome that.”

The news industry has also suffered from an erosion of the trust the public once had in the truthfulness and fairness of the information published, Sullivan said. That loss of trust, though not warranted in most cases, has hurt the fortunes and stability of the news industry. The constant criticism of the press by President Donald Trump has also hurt the standing of news organizations in the country and in communities, she said.

“The whole problem of mistrust and distrust in the news media is another underlying issue here,” Sullivan said. “There’s a huge amount of mistrust; people feel very strongly that news organization are biased, that they are far too liberal, that they don’t line up with their beliefs.”

That sentiment has also led to the rise of alternative news sources that intentionally slant the news or misrepresent the facts as a matter of course to support one political party or philosophy, she said.

Sullivan praised the recent emergence and success of non-profit news organizations, such as News Watch, that rely on donations and philanthropy for funding and do not rely on advertising. She said non-profit news organizations have done a great job in covering important news in a fair and complete way, Sullivan said. Still, at this time, non-profit news groups cannot fully replace the local news that daily and weekly newspapers once provided, she said.

To build back trust in journalism, to strengthen the role of local news in communities and to make consumers more savvy about the news they consume, journalism organizations and the public can take several actions, Sullivan said.

She suggested that schools could teach “news literacy” to inform young people about the importance of local news and to be better able to separate truth from fiction. She urged individuals, philanthropic groups and others to support non-profit news organizations. She said that news consumers can learn more about the sources of news they consume, including who owns the organization, what it stands for and if it has a history of accuracy and doing good journalism.

“It’s all a part of being a more critical consumer and a more sophisticated news consumer,” Sullivan said. “We have to teach people how to tell essentially what’s truth or at least is what’s trying to be truthful.”

Sullivan also said that front-line journalists and news organizations as a whole must continue to place a high value on fairness, openness, transparency and accountability.

“We as journalists have to make sure the people we are serving understand our role … and make sure that we’re holding ourselves to the highest possible standards of fairness, accuracy and ethics,” Sullivan said.

All those steps, she said, can help improve the viability of news sources that report on local events and happenings, hold government and the powerful accountable, and keep their communities informed on critical issues.

On other topics, Sullivan said:

— That ownership of the Washington Post by Amazon founder Jeff Bezos has helped stabilize the finances of the newspaper and that Bezos does not influence news coverage or editorial decisions.

— That news organizations should feel comfortable in labeling provable deceptive statements by President Trump as “lies” once it becomes clear the misstatements are not simply errors but repeated attempts to mislead the public. “When someone says something wrong or makes misstatements or bald falsehoods time after time on the same subject, I think it’s fair to call it a lie,” she said. “We know it’s not a simple misstatement or a slip of the tongue.”

— That she consumes a wide ranges of news sources but is not a big fan of the constant commentary of cable TV news. “Cable news is very exhausting and I don’t think it’s actually a healthy environment.”