BIG STONE CITY, S.D. – Kathy Tyler drove past a section of Grant County farmland she owns in the fall of 2016 and noticed that a metal culvert had been installed under a small driveway on her land.

No one had asked permission to be on her property or alerted her that the culvert might be installed. No one offered to pay for it. And no one seemed to listen to her objections when the culvert later was used to house a 6-inch diameter vinyl hose that carried thousands of gallons of liquified hog waste from a nearby corporate farm under her driveway and over her land.

Tyler said she eventually learned that Grant County officials had given permission to representatives from the privately-owned Teton LLC hog farm to lay the manure pipes in the ditches along several area roads. There was no application process, public hearing or public notice of the county’s decision. Hog plant operators had simply filled out a form and were allowed to run the pipes in the right-of-way along the roadside, Tyler said.

“I was so angry,” Tyler said. “This is my property and you haven’t asked for permission.”

Tyler, a former Democratic state house member, and her husband, Timothy, filed a lawsuit against the county, alleging their property rights had been violated. The lawsuit is pending

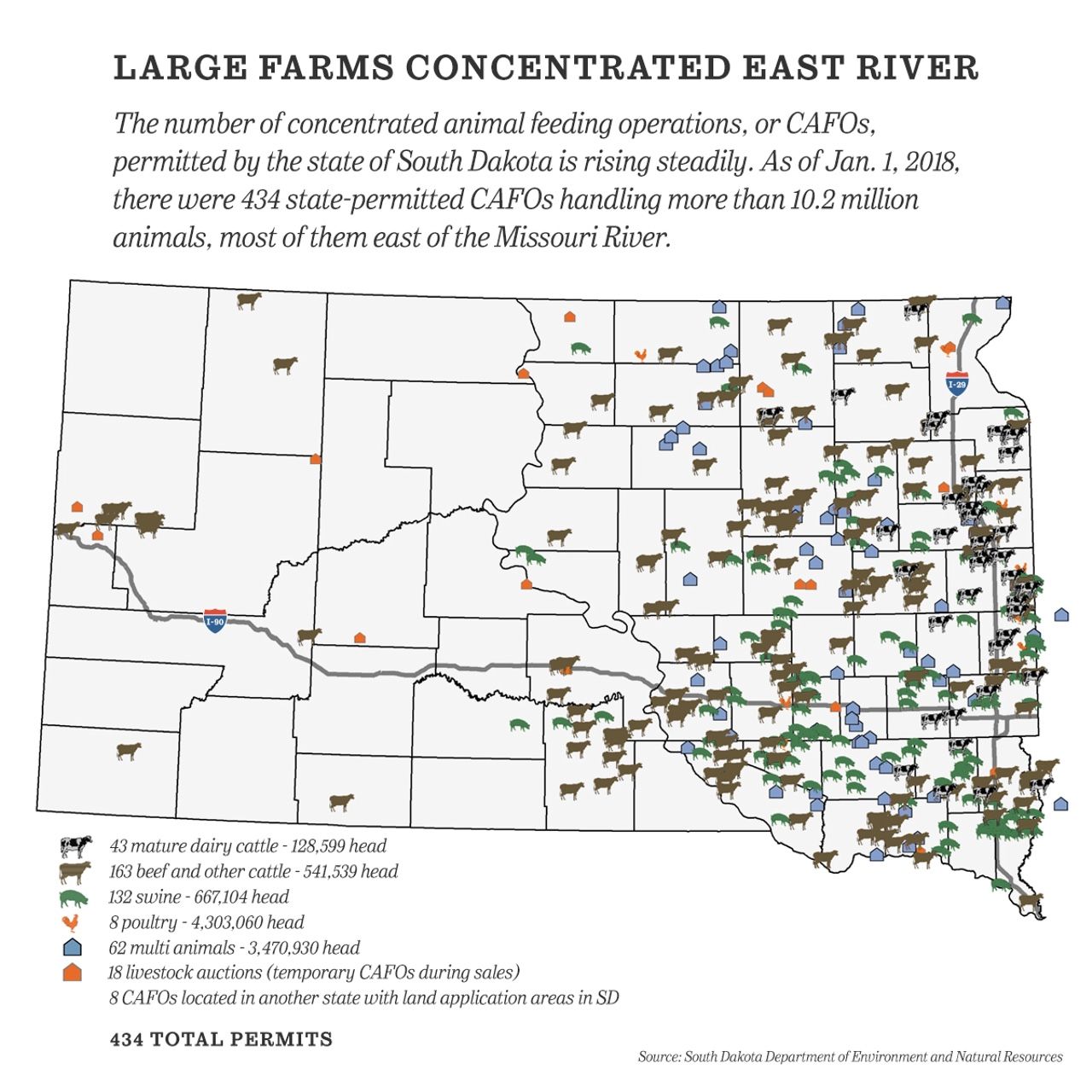

Manure piping and its potential infringement on individual property rights is becoming the latest battleground between large concentrated farming operations and their rural neighbors and other opponents. South Dakota has embraced the livestock operations, permitting more than 430 since the late 1990s. Environmentalists and others have continued to push for tougher zoning regulations and limitations on traffic, odor and water pollution potential from the farms. The waste piping concerns surfaced in the state legislature this year as lawmakers tried to clarify county officials’ role in the process.

Many issues arose during the legislative debate, including water-quality concerns, worries over the environmental consequences of concentrated animal feeding operations (CAFOs), fears that increased use of animal-waste tanker trucks will destroy rural roads, and claims that government and private industry are illegally using eminent domain to take private property without offering landowners compensation.

For now, the issues remain unsettled, and some rural landowners remain fearful they may wake up one day to find a pipeline full of hog, cow or chicken waste running through the ditch in front of their homes, and there may be nothing they can do about it.

Some neighbors give permission for piping

As of Jan. 1, 2018, the state has granted permits to 434 concentrated livestock feeding operations, most of them in eastern South Dakota. The operations that farrow or feed more than 10 million pigs, cows, chickens and turkeys generate millions of gallons of animal waste each year, and it must go somewhere. Most firms use hoses and pumps, and sometimes tanker trucks, to move the waste to nearby farm fields where it is injected into the land as crop fertilizer.

In most cases, CAFO operators like Hand County hog farmer Matt Moeller reach out to neighbors and get permission before laying the hoses. For nearly 20 years, Moeller has cultivated a cordial relationship with nearby property owners who give him permission to run hoses on their rights-of-way land or other private acres. The hoses run from slurry pits or lagoons at the feeding operations to crop land up to 10 miles away.

Many of the neighboring farmers pay Moeller for the pumping costs to have their fields fertilized by some of the 4.5 million gallons of manure his 11,000 young hogs produce each year.

“I get along with all my neighbors really, really well,” Moeller said. “If we need to get across a field, they say, ‘You bet, no problem at all.’” Moeller recalled a situation a few years back where a neighbor did not want the hoses used during an Easter celebration he had planned, and Moeller rearranged his piping schedule to accommodate the neighbor’s plans.

Moeller said his pumping and piping system has several safety measures, including automatic shut-off systems in the case of a leak. He said he has never had a spill or a leak.

The problem comes when neighbors do not support the farm or just don’t want waste hoses running across their land or in their ditch with no financial benefit. In Grant County, the Tylers fought construction of the livestock feeding operation in their neighborhood all the way to the state Supreme Court before losing in 2015. The plant, owned by Pipestone Livestock of Minnesota, can house up to 7,816 head of production hogs, according to its permit with the state Department of Environment and Resources. The Tylers see no reason to accommodate the plant’s desire to run pipelines across the rights-of-way near their home and property.

What’s right with right-of-way uses?

The South Dakota Constitution and Supreme Court case law indicate that the land beneath county and township roads is private property, according to attorney and land-use expert David Ganje of Rapid City.

While the state owns the land beneath South Dakota highways and interstates, and controls the use of those adjacent rights-of-way, private landowners who abut county and town roads and highways own the land up to and under the lanes to the middle of the road, Ganje said.

Private landowners pay taxes on that land and they must keep it free of obstructions. Unless legal exemptions are made, the only allowable public use is for cars and trucks, access by the public on foot, horseback or in recreational vehicles, or for public utilities like phone lines, power lines, municipal water pipes or cable TV. Landowners can grow and harvest hay from the rights-of-ways.

In cases where landowner permission is not granted to use the right-of-way, or when waste application farmlands are too far away, some farmers will turn to the more expensive option of trucking the wastes. State and municipal transportation officials say the trucks are hard on rural roadways, especially in the spring. Another, less-common method of transport features permanent underground piping systems from production plants to farm fields, according to Jason Roggow, an engineer in the DENR feedlot program.

Roggow said his department requires operators to notify the state when they intend to use state rights-of-way, and to alert counties when they want to use local rights-of-way. But the state has no role in determining whether or how county governments give permission to CAFOs for right-of-way usage, he said.

Land-use advocates and rural property owners say that providing landowner notification or requiring landowner permission is not usually part of the process at the county level. Since there is no state involvement in that part of the process, each county handles waste hose requests in their own way, and there is no system for tracking how counties respond to requests.

In Brookings County, officials say that while they don’t require landowner permission on CAFO right-of-way easement forms, they do give great weight to the rights and opinions of nearby landowners.

Brookings County Development Director Bob Hill said that to protect local water sources, his county does not allow manure hoses within drainage ditches. But the county does allow culverts to be dug beneath county roads so waste hoses can cross roads to get to nearby properties.

Hill said it is incumbent on the livestock operators to work with neighbors to make sure the landowners have granted permission for the use of their private lands. He noted that the Brookings County Commission denied a recent request for a manure hose easement in the right-of-way because a nearby landowner did not want it on the property. “We listen to concerns of all Brookings County residents,” Hill said.

Tyler said she went to the Grant County Commission to get answers and to stop the use of her land by the Teton hog plant. She said she was told the company had obtained permission and therefore was allowed to continue the piping. Shortly after, she filed the lawsuit.

Grant County Auditor Karen Layher said she was not authorized to discuss the lawsuit, and State’s Attorney Mark Reedstrom was out of town and did not respond to a request for comment.

Lawmakers take up issues

Possibly spurred by the legal issues in Grant County, the right-of-way issue arose in Pierre during the 2018 legislative session with the filing of House Bill 1184.

The Republican-led measure contained only two sentences, even after it was amended in a House committee. The bill would have allowed manure pipelines to be considered a utility in order to give counties authority to allow livestock feeding operators to place the hoses and lines in the rights-of-way.

The bill contained no references to liability for damages or injury, gave no inspection or permitting guidelines, and did not provide a framework upon which counties could enact a uniform approval process. It also never mentioned landowner concerns or whether landowner permission or notification would be required before right-of-way access was granted.

Rep. Jason Kettwig, R-Milbank, the main sponsor, said the measure intentionally “does not say, yes you can do that, or no, you cannot do that,” but rather was intended to give counties local control over how they regulate the use of rights-of-ways and the transport of waste from feeding operations. “It gives them the authority to make rules and do this the right way for their local area,” Kettwig said.

Backers of the bill included the state Department of Transportation, dairy farmers and hog producers, and the state township and county commission associations. Many proponents pointed to the efficiency of piping wastes and pointed out that hose systems avoid the damage waste tanker trucks do to rural roads.

“The practice of using road ditches to pump nutrients to fields for agronomic application has been a common practice for many years,” said dairy farmer Marv Post of Volga, who is also president of the South Dakota Dairy Producers, whose members manage 80,000 of the state’s roughly 120,000 dairy cows. “It provides a minimally invasive practice of transporting those nutrients without causing damage to our roads.”

Opposition arose on a more grass-roots platform of protecting property rights and a desire to ensure that waters that flow in ditches are not exposed to the potential of manure leaks or spills.

Kristi Mogen, a farmer from Twin Brooks, told the House committee that she can face fines if she does not maintain the right-of-way or if she allows an unauthorized private use. She pointed out that the state constitution prohibits government from making special laws to benefit an individual business. She also said the process of eminent domain or property condemnation by government requires a formal public process and financial compensation for affected landowners.

If passed, she said, the bill would make it possible that “somebody is using my land, and I have no say-so about it. Somebody’s making money off my land and it isn’t me.”

Environmentalists expressed worries that increased piping of wastes in drainage ditches could lead to leaks or spills of manure and damaging nutrients that eventually make their way into lakes and streams. Mark Winegar, a lobbyist for the Sierra Club, said the piping process lacks critical elements of regulation and oversight while the manure is being moved.

“We have no safety requirements for the transport of that material,” he testified. “The pressure applied by the series of pumps needed to pump out a sewage lagoon and force it through a vinyl hose several miles long can create geysers of animal waste from just a small pinhole,” Winegar said.

"We have no safety requirements for the transport of that material. The pressure applied by the series of pumps needed to pump out a sewage lagoon and force it through a vinyl hose several miles long can create geysers of animal waste from just a small pinhole."

More debate to come

The measure passed in a House committee and then through the full House on narrow votes, but later died in the Senate Transportation Committee on a 4-2 vote.

Senators said the bill raised too many unanswered questions and needed more work before it was ready for passage. Some also shared Ganje’s view that the bill as written was likely unconstitutional.

“If you’re taking private property, you have to give compensation, and there’s no taking without due process of law,” said Ganje, who writes a statewide column on land use and environmental issues. “Basically, what the counties would have been doing would be undertaking a condemnation or eminent domain procedure without following the rules.”

For now, people on both sides of the right-of-way issue are in wait-and-see mode as they watch to learn the outcome of the Tylers’ lawsuit against Grant County.

But, in an interview after his bill failed, Rep. Kettwig said he expects to bring another measure next session and use what he learned during the 2018 debate to craft a measure that accomplishes its intended goal with minimal controversy and opposition.

He wondered if there’s a way to give counties more regulatory authority without trampling on the rights of private property owners.

“I think these counties need to have the authority to control what goes on in those rights-of-way,” said Kettwig, the city administrator in Milbank. “I do think it’s something we need to get clarified in state law, so I do think this [bill] is going to come back.”