SIOUX FALLS, S.D. – With a wheelchair as his bed and a ratty checkered blanket as his covers, 63-year-old George VanVooren spent the night on a sidewalk outside the Bishop Dudley Hospitality House in Sioux Falls on a recent Saturday night.

"You get a couple hours of sleep – if you're lucky," he said.

The next morning, he parked his wheelchair in an alley next to the shelter and waited patiently for a physician with the Midwest Street Medicine program to attend to his ailing foot.

VanVooren said he lost one leg and part of his other foot to frostbite last winter when he arrived too late for entry into the shelter. His remaining foot is now just a reddish stub with a gap in the flesh where his toes used to be.

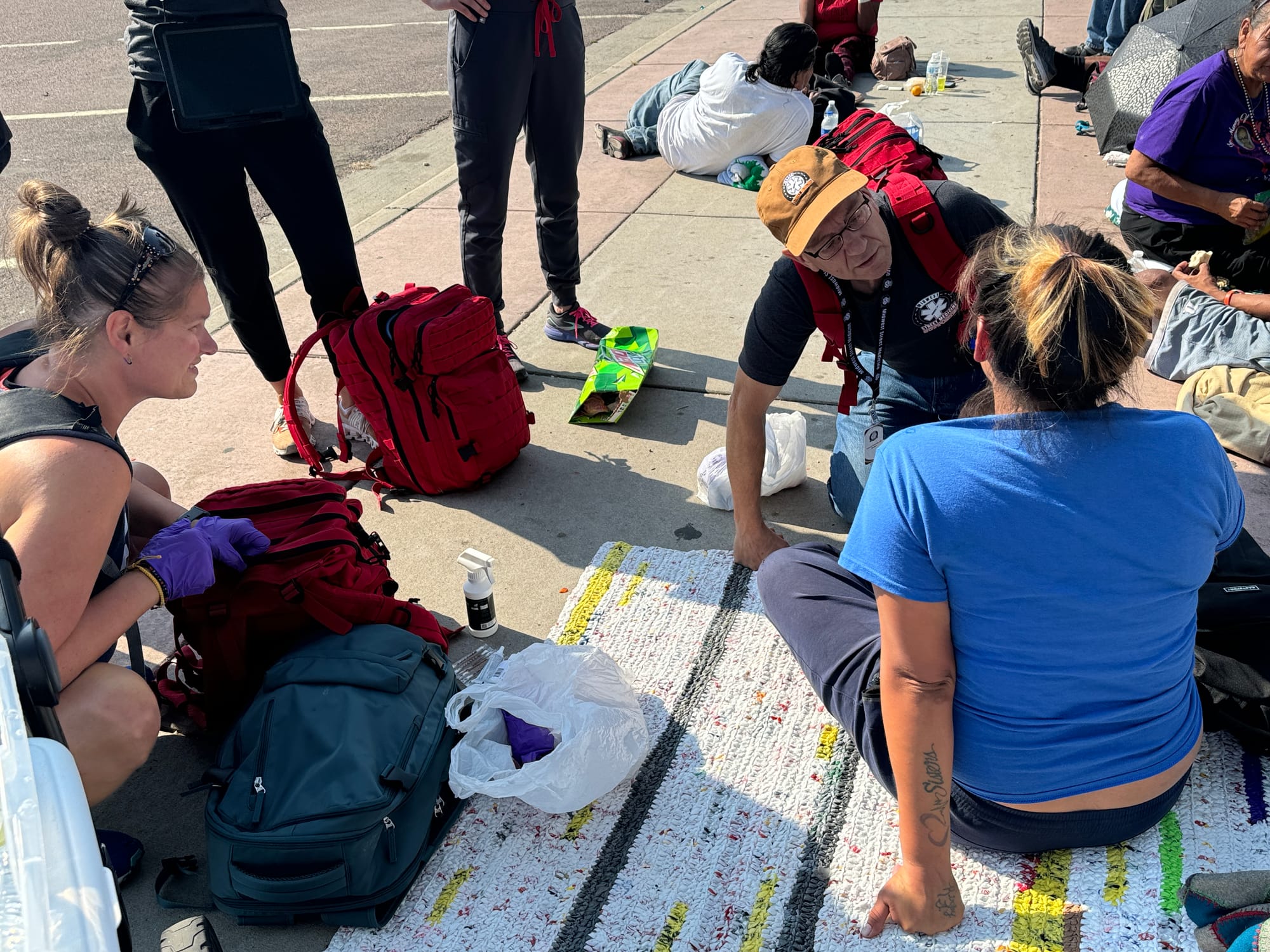

VanVooren sat stoically as Bob Santella, M.D., a retiree who volunteers with Midwest Street Medicine, applied surgical gloves and began to remove the dirty gauze that was wrapped around the foot.

Suddenly, a putrid waft of odor – akin to the smell of rotting meat or fouled eggs – filled the air as the blood-stained gauze was unfurled, only to reveal a mass of maggots that were crawling and feasting on the flesh of VanVooren's stub foot.

"Oooh, there's maggots here – a lot of them," Santella said.

He brushed the maggots off the foot and onto the pavement below, then rolled VanVooren's wheelchair a few feet away. He and a volunteer nurse used an alcohol solution to wash the foot before Santella re-wrapped it with clean gauze and a fresh sock.

"How long since that was cleaned?" the doctor asked. VanVooren replied it had been a week – "since the last time you guys were down here."

Bringing care directly to those in need

The Midwest Street Medicine program launched in Sioux Falls in July 2023, largely through the efforts of Shannon Emry, M.D., a pediatrician at Avera Health. Emry told News Watch she created the program after seeing similar projects improve health outcomes for homeless people in other cities around the U.S. and the world.

Emry said she was always interested in improving "health equity," or the ability of all people to obtain life-saving or life-prolonging medical care. But her concerns were amplified during the COVID-19 pandemic and seeing how South Dakota's Native American population was disproportionately hurt by the virus.

Soon after, the idea to launch the street medicine program took hold. "I thought, 'This is where we can make a real difference in health equity and life expectancy,'" she said.

Emry said the strength in street medicine lies in the ability of volunteers to make a fairly large impact with relatively small procedures or actions. Bringing medical care to the streets also sidesteps many of the financial, geographic and logistical barriers that prevent homeless people from obtaining health care. The health treatments aid people who otherwise might end up in emergency rooms or even dead if they don’t get the basic care they need.

"I realized we can make a big difference with pretty small interventions," she said. "Just making sure people have access to medications – that's a fairly easy way to make a big difference that might go a long way to helping some have longer life expectancy."

As the program grows stronger, Emry hopes to expand into other South Dakota communities where unhoused people are in need, including in Rapid City.

"That's always been our long-term goal, to help people in other cities in our region," Emry said. "We'd like to make a tool kit of sorts for them to use and follow."

An Army veteran with limited options

VanVooren, a native of Sioux Falls who said he served in the U.S. Army in the early 1980s, became homeless a couple years ago for reasons he chose not to discuss. He used to be a metal worker who built water towers, including one in central Sioux Falls. His only indoor time now comes when he and his girlfriend get paid – her from work and him from disability – so they can pony up for a couple nights in a motel.

VanVooren said he feels almost no pain in his stub foot due to a previous fasciotomy surgery that removed pressure in his infected leg but also deadened the nerves in his leg and foot.

Santella urged VanVooren to try to change his bandages more frequently if he could to keep his foot clean and dry, but he also promised to check on him during his street rounds the following week.

VanVooren is well-known to the street medicine volunteers and leaders, who have plans to add him as a member to their governing board. "I love these people," VanVooren said. "If it wasn't for them..."

Team effort to help those in need

Each month, a retired farm family from Parker that still raises laying hens, gathers a gaggle of helpers to produce about 150 to 200 egg-salad and cheese sandwiches. The sandwiches are dropped off at a meeting spot in Tea, where a volunteer picks them up and brings them to Sioux Falls to be handed out to unhoused people during the street medicine rounds.

The sandwiches, bottles of water, cheese sticks and granola bars are given to people on the street to nourish them but also as an ice-breaker to make them feel comfortable enough to share information about their health problems or conditions that need care.

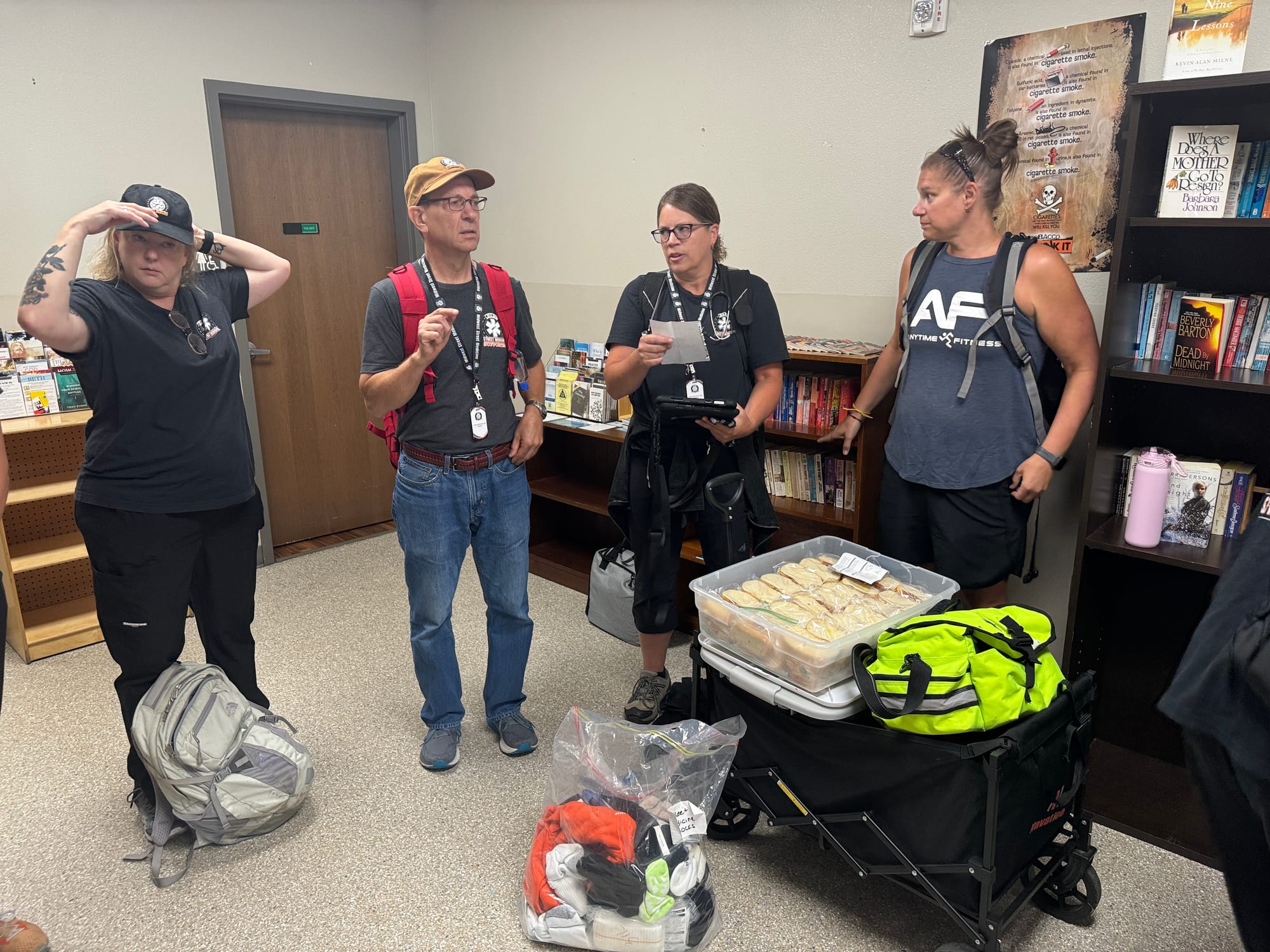

On a recent Sunday, a group of about 20 volunteer medical providers gathered inside a hallway at the Bishop Dudley house in Sioux Falls. They encircled a pair of rolling carts that contained food, water and clothing, and most critically, medical supplies and equipment. The physicians among them also had backpacks with more sensitive medical devices and supplies.

During a brief meeting before they hit the streets, Emry gave the volunteers some guidelines and advice. First, some basics: Approach people slowly and with respect to their privacy; remain cautious while providing care; share knowledge and resources while in the field; and maintain accurate written records of patients and the care provided.

"My heart is so full that you're all here," she then said. "But remember, we're not here to be right or to tell people what to do or how to live. We're here to listen and to help."

Even before they hit the streets, group co-founder Melissa "Dr. Mo" Dittberner, Ph.D., noticed a young woman with glazed eyes and a sad expression standing wistfully aside from the medical group.

"Do you need a sandwich, honey?" she asked. The woman replied that she could really use some socks. A volunteer responded by handing her a couple of clean pairs along with some granola bars.

Midwest Street Medicine fueled by grants and volunteerism

While Emry hopes to eventually draw a small salary, Midwest Street Medicine is operated exclusively through donated labor. On a typical day, medical practitioners might include doctors, nurses, physician assistants, pharmacists or counselors. Non-medical volunteers are also present to hand out food and basic necessities to patients and help keep records.

So far, Midwest Street Medicine has run on a combination of grants, donations and a small amount of seed money from the state's portion of a national settlement with opioid manufacturers. The group received a $60,000 commitment over two years from the Sioux Falls Area Community Foundation in spring 2024 and learned in late June that the South Dakota Community Foundation was providing a $90,000 grant.

Medical crews provide care on Sunday and Monday mornings, tending to a wide range of issues common among the chronically unhoused residents of the city. The program provides no-cost care to homeless people with medical, behavioral and substance abuse conditions and also provides funding for medication co-pays for patients.

As of August, Emry said the program had provided more than 1,000 medical interventions to more than 350 patients, about 80% of whom are Native American.

Often, people end up on the streets due to mental health conditions, addictions, disabilities or when several crises crash down upon their lives at the same time.

The process to find patients is simple: the street medicine teams walk around neighborhoods where homeless people congregate and ask people if they need any help. Most of those helped by the medical teams are chronically homeless.

A retiree with time, and skills, on his hands

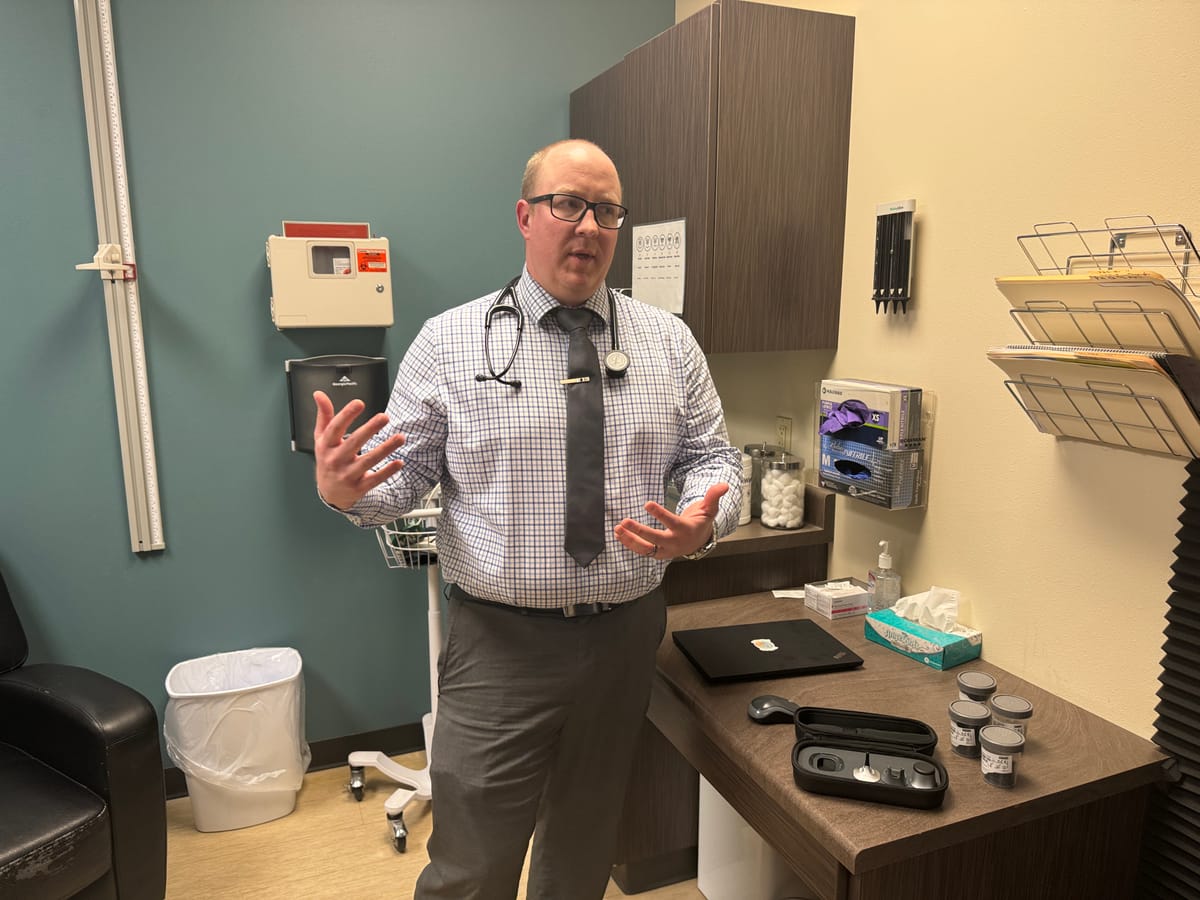

After retiring from Avera Health as a nephrologist, or kidney doctor, Santella said he volunteered with Habitat for Humanity but felt he could do more.

"I thought, 'I’m trained as a physician,' so why not do this?" Santella said as he walked along East 8th Street in Sioux Falls looking for patients. "I feel like I’ve had a nice life and wanted to do a little more giving."

Santella said his most common patients have frostbite in the winter and suffer from heat exhaustion in the summer. He said cuts and wounds are another area of frequent need for care.

Some members of the street medicine crew were upset in early August over comments made by Sioux Falls Mayor Paul TenHaken and Police Chief Jon Thum, who suggested that people should stop giving panhandlers money. In a joint email to News Watch, both officials praised the efforts of outreach organizations such as the Bishop Dudley house and Midwest Street Medicine.

In the email, the two leaders said a few people are taking advantage of local services and are frequently engaged in "disruptive and illegal" activities that stress the police department and other community resources.

"What we have seen this summer though is a small group of individuals refusing a hand up, taking advantage of our compassionate community, and occupying our Police Department’s time and resources because of these individuals’ disruptive and illegal behavior, especially throughout our downtown," TenHaken wrote. "We are asking our community to stop giving individuals cash, blankets, and food, and instead donate to the organizations already providing these services or give their time for mentorship to make an impactful difference."

Santella rejected any notion that helping homeless people with medical care was "enabling" them to remain living on the streets.

"To help people with medical care they can't receive otherwise, I don't see how that enables houseless-ness at all," he said. "If I didn't stitch up that lady's face, and she got infected, how is that any benefit?"

Santella added: "We don't say if people should be sleeping outside or not. All we do is take care of them, and that's it."

Stitching up wounds, removing scalp staples

In a three-hour period, Santella treated VanVooren's foot and provided at least two other significant medical interventions. He and team members also checked blood pressures, wrote prescriptions and performed wellness checks on about two dozen people.

Without fanfare or drama, Santella at one point called to his crew mates for a staple remover. The doctor was alerted to a man who was in a fight and received scalp staples a while back but had neglected to get the staples pulled when required.

"I'm just going to warn you, this isn't going to feel great," Santella told the man.

Within a minute, he had removed four surgery stitches from the head of Branden Marshall, 44, who is well known on the streets around the Bishop Dudley center and goes by the street nickname "the Surgeon General."

Santella asked Marshall what happened to cause the head injury and he replied that he'd been in a fight "with someone who didn't like my attitude."

Like all those treated by the street medicine volunteers on that Sunday morning, Marshall expressed deep appreciation for the care and food he received.

"They're good people, very nice people who give up their time to help others," Marshall told a reporter. "It makes the heart feel really good."

Healing wounds from a knife fight

Santella's most invasive treatment involved stitching up a facial puncture and an abdominal wound on a woman who had been stabbed.

After providing basic triage on the street, Santella, two nurses and the patient went into the Bishop Dudley house, where they worked in cleaned conditions in a small patient room. The team laid the woman on a table and Santella began to wash out the cut on the woman's face.

"It's actually quite deep," Santella said of the puncture wound.

The patient moaned in pain as Santella used a needle to pull together the skin around the wound and sew it shut. The two assistants held the woman's hands and whispered kind words to help steady her during the procedure.

A bit later, Santella also cleaned and dressed the woman's small stomach wound, which was not as deep. He added antibiotic cream and a bandage to fully close and secure the wound.

"OK," Santella said, "You're good as new."

Dittberner said she heard the woman had been kicked out of the Dudley house for bad behavior and also was banned from a local women's shelter because she refused to attend chapel services.

"There's so many barriers, so many," Dittberner said. "And people say, 'Why don't they just try harder?'"

As Santella worked, a nurse took the woman's blood pressure, which was found to be normal. "Keep up the good work on that," she urged the patient.

Santella then urged the woman to keep her dressings clean and asked her to look for the street medicine team the next week to get further medical care.

"Just remember, we have to see you next week to take those stitches out," he said.

Then, with that advice and two neatly cleaned and bandaged wounds, the woman left the shelter and headed back out onto the streets.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit news organization. Read more in-depth stories at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email every few days to get stories as soon as they're published. Contact Bart Pfankuch at bart.pfankuch@sdnewswatch.org.