Thousands of schoolchildren across South Dakota are facing new barriers to getting proper nutrition at school due to the end of a pandemic-era federal program that provided free meals to all students regardless of parental income.

Parents in South Dakota, meanwhile, are facing new financial challenges as they try to pay for meals for their children at a time when high inflation rates are driving up costs for food, energy, housing and many other necessary goods and services.

The federal effort to provide free meals to all American schoolchildren during the COVID-19 pandemic expired this summer. The pandemic-era program provided more than 4 billion free meals over the past two school years, including to tens of thousands of students in South Dakota.

Sioux Falls School District Superintendent Jane Stavem told News Watch that ending the free school meals program after two years has put the district, parents and children in tough spots.

The district does not have the funding to continue to provide free meals for all students on its own, and is working on innovative ways to continue to pay for food for students who need it.

Parents who got used to free meals for their children for two years are out of the habit of preparing or paying for student meals on their own, Stavem said. Some who qualify for free or reduced-price lunches due to low incomes forgot to reapply for the federal school lunch program and will now have to pay full price for meals.

And children who are not given food by their parents or who cannot afford to buy a school meal on their own are going hungry and can fall behind in class or be unable to concentrate due to hunger, Stavem said.

“They’re just going to be focused on how hungry they are,” she said.

Stavem said districts across the state and nation are trying to navigate a return to paid student meals at a time when inflation is hurting both schools and families. And yet, the student meal issues must be solved, either at the local or federal level, she said.

“We have an obligation as a country that provides a free and appropriate public education for all kids, to also look at the aspects of providing nutrition for all kids,” Stavem said.

School officials across South Dakota told News Watch that a student in need of a meal is not turned away.

However, the inability of a child to obtain adequate levels of nutritious food can affect their development now and well into the future, said Stacey Andernacht, a spokeswoman for Feeding South Dakota.

“A majority of an individual’s brain development happens from birth to five….so good nutrition is essential for kids and missing those meals is something that can impact a child in a way that makes them less successful in life,” Andernacht said. “When you have kids showing up to school without breakfast or not having lunch, they’e unable to focus, they’re going have problems paying attention, which will lead to learning problems, and they’re also more likely to have chronic health issues because they’re bodies are going without.”

Sioux Falls district officials began contacting parents as early as May 2022 to let them know that the free meal program was likely to end before the 2022-23 school year started, said Gay Anderson, student nutrition director for the district.

Officials wanted to give parents plenty of time to make plans to either reapply for federal meal assistance or prepare to pay for breakfasts and lunches once again.

However, statistics from within the Sioux Falls schools show that far fewer schoolchildren are receiving meals at school so far this year, with rising inflation and the end of the universal free meal program seen as main causes.

In the 2021-22 school year, when meals were free for all of the roughly 25,000 students in the Sioux Falls public schools, the district provided on average 16,500 lunches and 6,800 breakfast meals to students each day.

So far this school year, only about 3,800 students are eating breakfast at school daily (a decline of about 3,000 students, or 44% lower than the prior year); and about 13,400 students are having lunch provided at school daily (a decrease of 3,100 students, or 19% lower than last year.)

The national free meal program provided 4 billion free meals to students during the past two school years. The pre-pandemic school nutrition program provided about 3 billion free or reduced-price lunches and cost the federal government about $14.2 billion annually. Providing free meals to all students would raise the cost of the program by about $10 billion a year.

Stavem estimates it would cost the school district about $5 million a year to continue the free students meals program without federal funding.

The district is also facing higher costs to provide meals, with food costs up about 18% this year compared to 2021-22 and labor costs significantly higher as well.

Stavem said that despite aggressive efforts by the district to inform parents that they needed to reapply for the free or reduced lunch program when the free meals ended, some families forgot to apply or did not apply for other reasons.

Meanwhile, wages in South Dakota rose during the pandemic as businesses tried to attract and retain employees, but those wage hikes kicked some Sioux Falls families out of the free and reduced lunch program that is based on family income. In the 2019-20 school year, the district had about 11,300 students in the free or reduced lunch program, and only about 400 families were denied entry because their incomes surpassed federal guidelines.

So far in the 2022-23 school year, only 10,400 students are in the free or reduced price lunch program, and 1,042 were denied due to exceeding federal income standards, district data show.

For example, Anderson said she knows of one father whose income was $47 a year too high to qualify for reduced-price school meals. His increased pay clearly did not cover the new costs of paying for meals for his children at school, Anderson said.

Stavem said she sympathizes with parents and especially with students, many of whom are forced to navigate a complicated system involving their parents, their school, federal regulations, a stigma of asking for financial help, and in the end, a need to satisfy their own hunger.

“What it comes down to, regardless of the politics involved in this, is that children are at the mercy of adults for this whole picture … and It is not the fault of that child,” Stavem said. “For us really, it comes down to that bottom line of never wanting to see a child in a lunch line facing that reality of not being handed a meal.”

Need for food high across South Dakota

Feeding South Dakota, the largest provider of charitable food in the state, has seen significant increases in the need for food among adults and children across the state so far this year, said Andernacht, spokesperson for the nonprofit group.

The organization’s backpack program, which provides a backpack full of healthy food to schoolchildren on Fridays so they have food at home for the weekend, has seen a big jump in need among families already this year.

In the first week of the 2022-23 school year, in early September, Feeding South Dakota distributed 3,082 backpacks to children in South Dakota regardless of family income. The following week, distribution of backpacks rose by nearly 30% to almost 4,000 backpacks handed out at the 82 schools served by the program.

The end of the universal free meal program coupled with high inflation are increasing the need for food among lower-income families across the state, Andernacht said. From August 2021 to August 2022, the organization saw a 40% increase in the number of families visiting its mobile food banks in South Dakota. Over the past three months, Feeding South Dakota has served an average about 11,150 families monthly at its mobile food pantries, she said.

“Pandemic-era government programs are ending, and many things, food among them, are incredibly more expensive right now, so that’s a bit of a perfect storm for a lot of our families,” Andernacht said. “And we’re seeing more people use our services for the first time.”

Obtaining and affording healthy food is an even greater challenge for rural residents of South Dakota, where some grocery stores closed during the pandemic and others are charging much higher prices than in more competitive urban areas, she said.

Food insecurity — defined as the inability to afford or get access to sufficient amounts of healthy foods — remains a nagging problem in South Dakota, both for those families with low incomes and for those who make a living wage. According to the Feeding America Map the Meal Gap database, nearly 75,000 South Dakota residents (about 9% of the population) were considered food insecure in 2020, and only half of those qualify for some level of federal food assistance. Food insecurity was highest in Native American communities and reservation areas, according to the database.

The data show also that in 2020 about 29,000 children in South Dakota were considered food insecure, with about a quarter of those unable to qualify for any federal food assistance. With 13.6% of all children in South Dakota facing food insecurity, the state has the highest rate of food insecurity among children in all neighboring states, according to the database: North Dakota (4.8%), Minnesota (6.0%), Iowa (7.3%), Montana (8.5%), Nebraska (9.8%), and Wyoming (10.2%).

Andernacht added that the universal school meal program in place during the pandemic reduced the potential stigma attached to receiving free or reduced meals at school, Andernacht said, because all students received free meals and not just those who income qualify.

“That was a nice thing about the free lunches for all is that it removed that stigma because everybody was getting the same thing,” she said. “In the Midwest, we are proud and it’s hard for people to ask for help, so we work try to remove that stigma because it’s more important than anything to receive good nutrition.”

Free and reduced-price student meals are provided under the National School Lunch Program, which in Fiscal 2020 provided 3.2 billion student meals, 77% of which were at a free or reduced rate. The following year, the program provided 2.2 billion meals, 99% of which were free. The federal school lunch program cost $14.2 billion in 2019, according to the USDA.

In the current school year, a family of four can qualify for free school lunches if their gross annual income is $36,000 or less; a family of four can qualify for reduced-price lunches if they make less than $51,000 a year.

Anderson said the prices for student meals are kept as low as possible, and that right now, the Sioux Falls district is losing money on each meal sold to students.

The cost for hot lunch is $3.05 per meal for elementary students and $3.25 for middle and high schoolers; breakfast costs $2.15 per meal at the elementary level and $2.25 for all others. That means a parent who doesn’t qualify for government assistance or who has not applied for help pays about $110 a month to feed a child at school, Anderson said.

One teacher’s fight against hunger

Rapid City geography teacher Bill Egan feels pain in his heart when he thinks that any student might be hungry and is unable to get the food they need.

Egan, along with other teachers at his school, have long provided snacks for students who might need a boost of nutrition to make it through the day or to someone who forgot their lunch.

But since the universal free meal program ended, Egan has witnessed a far greater number of students who need help.

“This year, I noticed there are so many kids not eating and you ask them why, and they say they can’t afford it or they have zero money in their lunch accounts,” Egan said “Their parents’ real income has gone down with inflation, so some parents are struggling to feed their kids.”

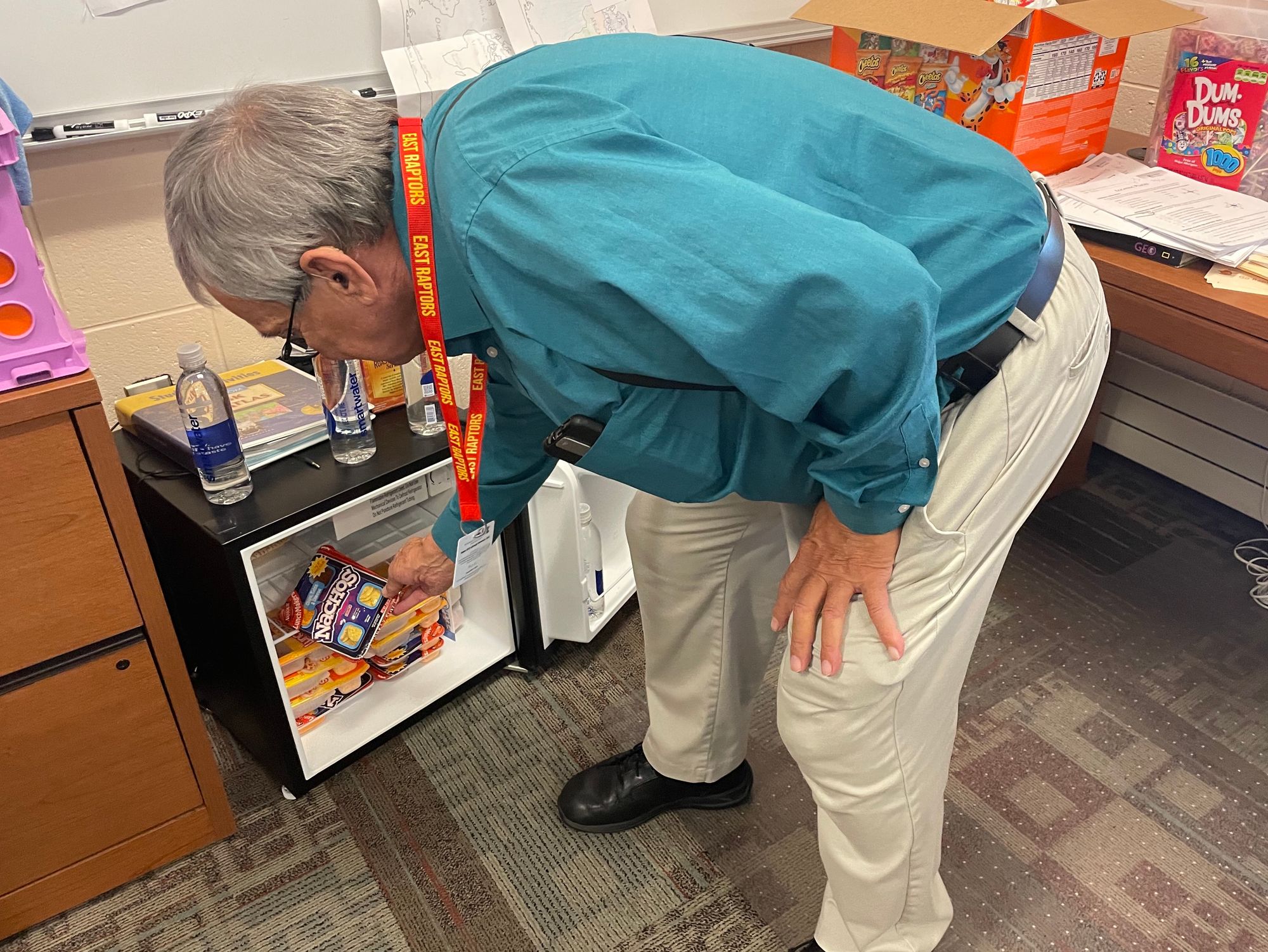

For the first few weeks of the new school year, Egan has spent his own money at Sam’s Club to buy bulk orders of “Lunchables,” the prepackaged trays of snacks that typically include slices of turkey, cheese, crackers and fruit (some also include a single cookie.)

Along with bags of chips and snacks he keeps in his classroom at East Middle School in Rapid City, Egan has a dormitory fridge stocked with Lunchables that he discreetly gives to students who don’t have money for hot lunch or who didn’t bring a lunch to school.

“I told the kids that if they can’t afford their lunch, or they forget their lunch, to come see me and I will give them a Lunchable,” Egan said. “I probably go through eight to 10 Lunchables a day at this point.”

For Egan, that expense is well worth it. Egan is 71 years old and has two retirement plans in place from his previous career as a police officer in Rapid City and then as a teacher in Texas. He’s taught in Rapid City for seven years.

“I just don’t want to see a kid go hungry,” he said. “When it costs me 97 cents from Sam’s to feed a kid, then I’m going to do it.”

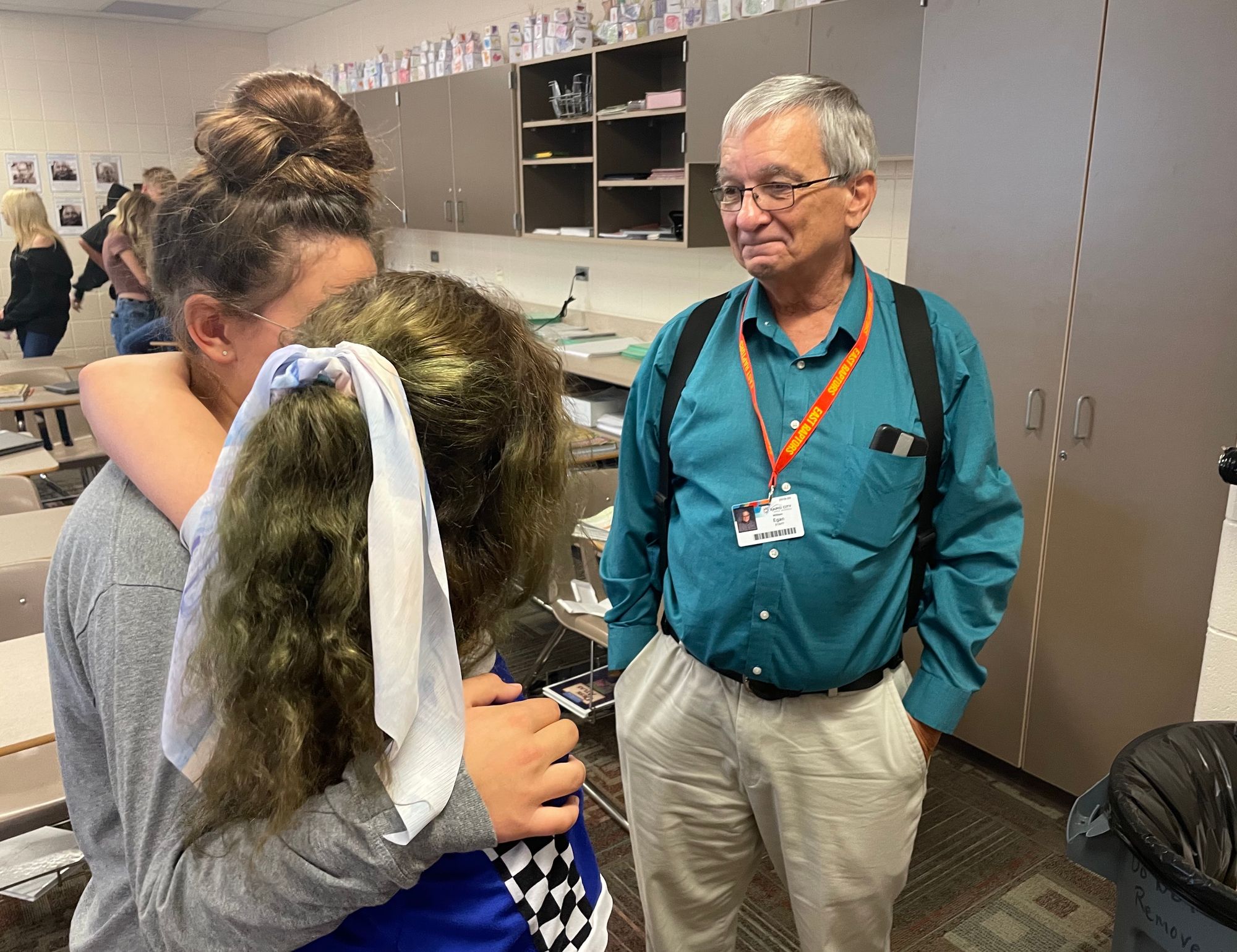

Egan said he treats students with kindness and respect, and his approach is returned in full by students who work hard in his class and try to impress him by following the rules and behaving well.

“I really don’t need the money, so I do this because I genuinely like these kids,” he said. “I’m a friendly teacher, and I like to create positive relationships with the kids because if the kids like you, they’ll behave for you and do their assignments and get down to work because they don’t want to disappoint you.

Egan said he recently gave a girl $5 so she could buy a meal while on a field trip — no questions asked. He provides snacks to any student who is hungry and pops into his classroom to say hello. Egan said he doesn’t ask students about problems at home, deciding instead to allow students to maintain their privacy and dignity.

One student of separated parents told Egan that when she stays with her mother, she gets a sack lunch to take to school. But when she says with her father, she goes to school hungry.

“I have kids that are sharing their lunch with other kids because they’re friends and they don’t want them to go hungry,” he said.

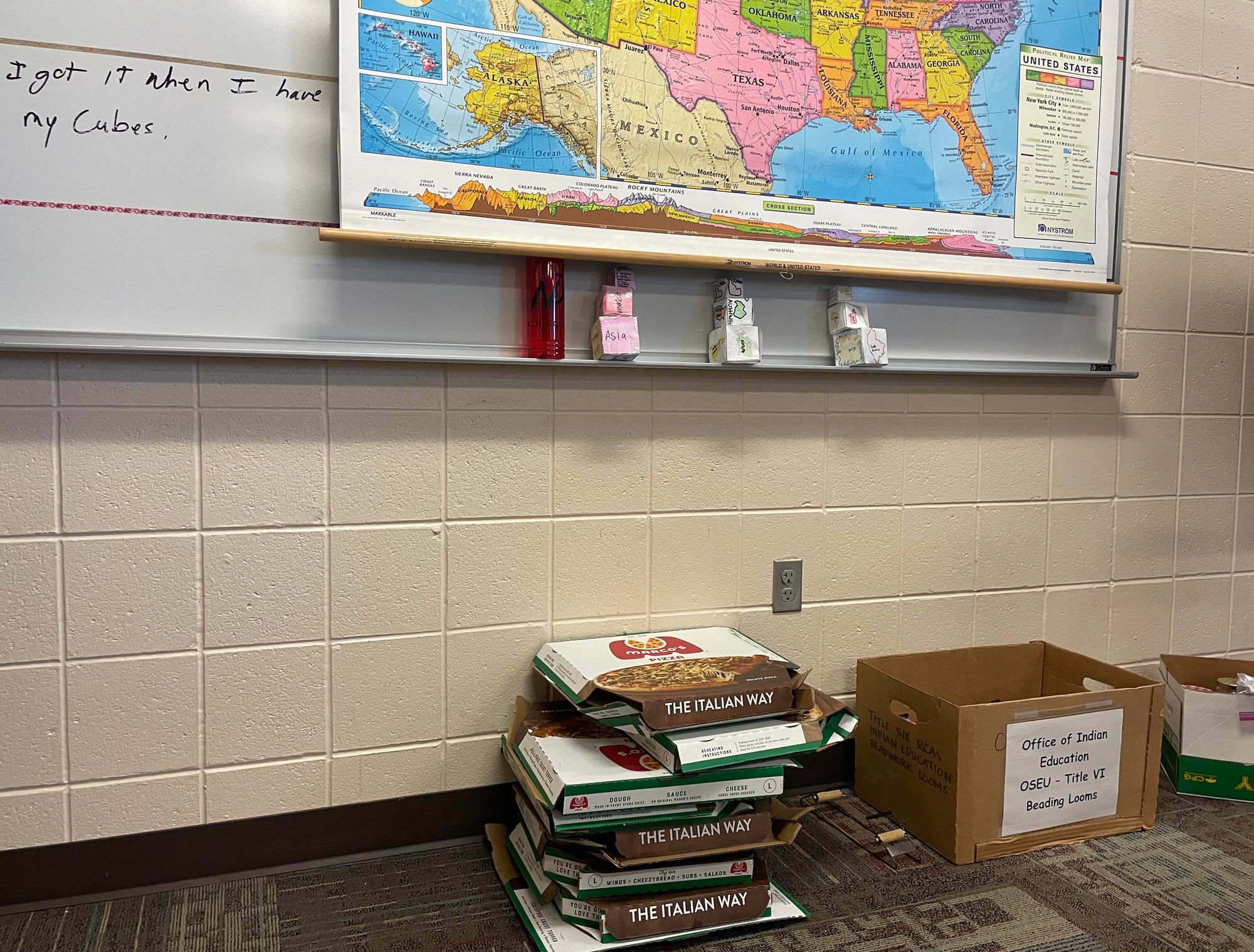

On a recent day at the school, Egan spent about $100 of his own money for several pizzas for a monthly lunch party he hosts for students who get all their work done and who behave well in school. Students vie to get a party invite, and Egan rotates the roster so more children have a chance to grab a slice or two (or three!). Egan said he noticed that some students who were about to miss out on the party in September had quickly caught up on all their work in order to attend.

As Egan spoke with a reporter from News Watch, students who had finished scarfing down on pizza chatted and giggled in Egan’s classroom.

“He’s the best teacher ever,” one girl shouted out.

Egan, touched by the comment, said softly, “Well, that’s nice to hear. I think they know I care about them.”

Egan said he will continue to provide food for students who need it, and even his friends have joined the effort.

“I had a guy at the Moose Lodge give me $70, and he said, ‘Buy them some food for me,’” Egan said.

Egan said he hopes the federal government can find a way to bring back the universal free school meals program and make student nutrition a greater priority in America.

“We didn’t have this problem the last two years, because kids could all get free breakfast and lunch,” he said. “We should not live in a society where kids go hungry, period. In a nation that’s supposed to be the richest nation in the world, and the best country in the world to live, we should not have kids hungry in our schools. We can send billions of dollars everywhere else, but we need to take care of our future, and our future is our kids.”