The COVID-19 pandemic has pushed more Native Americans living on reservations in South Dakota to seek homeownership, a potential step toward greater family financial security and community stability in some of the state’s most impoverished regions.

But long-standing institutional, economic and geographic barriers continue to block some reservation residents from buying a home.

During the first six months of 2020, 193 people enrolled in first-time homebuyer and financial literacy classes offered by reservation-based community development groups as a prelude to buying a home. During all of 2019, 190 people enrolled in the courses, according to data collected by the South Dakota Native Homeownership Coalition.

The first six months of 2020 also saw lenders close 40 home loans for a combined value of $3.8 million with Native American homebuyers. In all of 2019, lenders closed 47 loans worth about $3 million. Data from the second half of 2020 is not yet available.

“The number of people that are pursuing homeownership [on reservations] sounds like it is on track to double at least,” said Tawney Brunsch, a member of the South Dakota Native Homeownership Coalition board.

One of the driving factors behind the surge in interest in homeownership has been the pandemic itself and how the risk of spreading the virus affected how and where people live.

Red Dawn Foster, a state senator from Pine Ridge, lived with her grandparents until the pandemic struck in March 2020. After the 2020 South Dakota state legislative session, Foster started living in a recreational vehicle with no running water outside her grandparents’ home and sometimes pitched a tent in a friend’s yard to avoid exposing her grandparents to COVID-19. Foster spent the summer and fall of 2020 camping in yards and driveways while trying to buy a house of her own.

“Part of why COVID has hit our community so hard is that you have multiple generations living in one household,” Foster said. “Sometimes it’s great and amazing that there’s enough room for everybody, but other times it is a burden and a hardship, and it puts the community and our families at risk.”

Multi-generation households are common on South Dakota reservations partly because there is a severe shortage of available housing. Housing is so scarce on South Dakota reservations that up to three generations of some families live in a 1,200 square-foot home. In a few cases, as many as 17 family members live in one house, Brunsch said.

Such cramped conditions became untenable during the multiple pandemic-related lockdowns on reservations in South Dakota. During lockdowns, many adults were forced to work from home or lost their jobs altogether and forced children to attend school remotely via often poor internet connections.

Crowded homes also were potential breeding grounds for the coronavirus. Many Native Americans who otherwise didn’t think homeownership was in their immediate future have taken a new look at buying their own home, said Sharon Vogel, director of the Cheyenne River Sioux Tribe Housing Authority on the Cheyenne River reservation in central South Dakota.

“We’ve had a lot of people reach out to say, ‘I want homeownership right now. I want a safety net to protect my family,’” Vogel said.

Owning a home has long been a bedrock of family stability and financial security in the U.S. But Native Americans who live on reservations have not had the same opportunities to buy or build their own homes as other Americans.

Most Native Americans living in South Dakota either rent their homes or apartments or live with relatives. Renting does comparatively little to help families or individuals to develop long-term wealth or security, experts say.

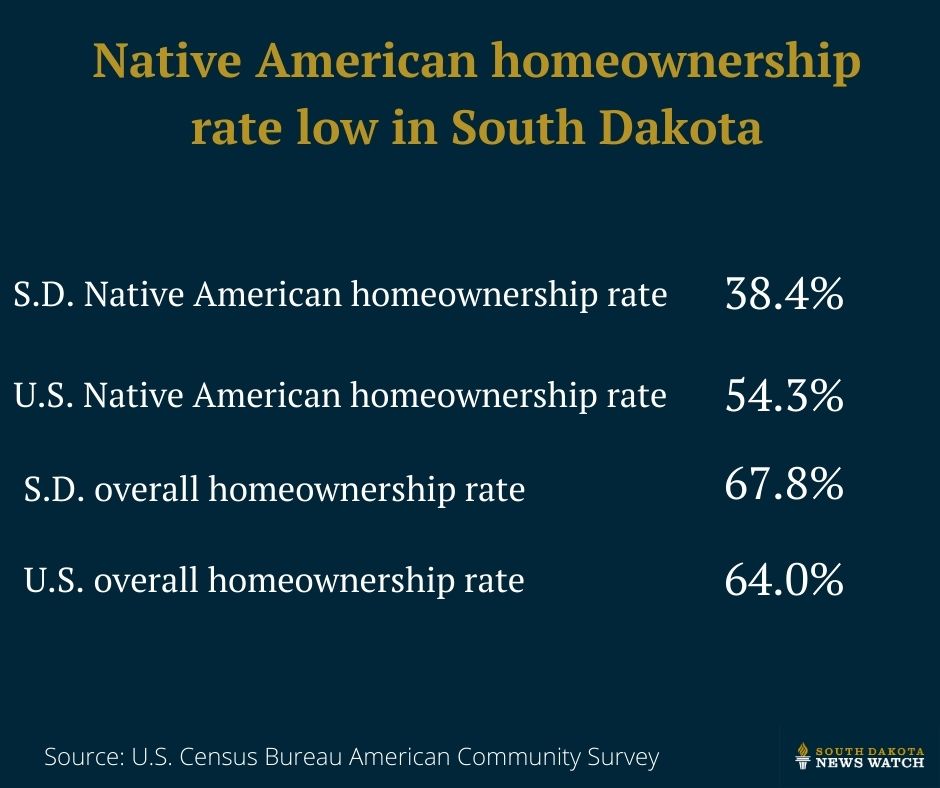

The latest U.S. Census Bureau data show that about 38% of Native American households in South Dakota live in homes they own, while roughly 72% of white South Dakotans own their homes. Nationally, and in South Dakota, the disparity in homeownership rates is a big piece of the wealth gap between Native Americans and non-Natives.

A 2019 U.S. Federal Reserve Bank survey of consumer finances found that homeowners were roughly 40 times more wealthy than renters at nearly every income level. Even at a relatively low household income of about $26,000, people who owned their homes had an average net worth of $102,000, according to the 2019 survey. Renters at the same income level had an average net worth of about $1,500.

The median household income on the Pine Ridge reservation is roughly $26,700. Data on household net worth for Native Americans hasn’t been published by the Census Bureau for at least two decades.

A higher financial net worth makes starting a business, buying a car or retiring much easier. Weathering economic hardships such as job losses or unexpected medical bills also is easier for people with more wealth.

Homeownership carries several intangible benefits. Numerous studies have shown that homeowners tend to volunteer in their communities more often, are more committed to making their communities safer and vote in higher numbers, said Casey Lozar, director of the Center for Indian Country Development at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank.

“Oftentimes, you see people migrating away from reservation communities. But with homeownership, tribal families really have the opportunity to stay in their community, to be involved in and to participate in their cultures and their traditions, to pass their language on to their children and to just really be engaged at the community level,” Lozar said.

While interest in homeownership has increased on South Dakota’s Native American reservations, significant barriers to buying or building a home remain. If nothing else, Foster said, COVID-19 has highlighted the importance of safe, affordable housing.

“If we don’t address this housing crisis now, as we grow as a state, it is going to be a much, much bigger issue in the future,” Foster said.

Knowledge gap, housing shortages are hurdles

Oglala Sioux Tribe member Alvina White Bull started taking the idea of buying a home seriously in 2016. At the time, the U.S. Army veteran was homeless and living in a shelter on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation with her 9-month-old grandson.

White Bull, 59, had recently completed a drug-related prison sentence and was determined to give her grandson a safe, stable place to live.

“I always wanted a home of my own,” White Bull said. “I know I still have to pay for it, but instead of going to rent, my money will go towards my own place where my family — my kids and grandkids — will always have a home.”

White Bull found a job as a driver and housekeeper at the Indian Health Services clinic in Pine Ridge and, in July of 2016, was able to rent a home through a federally funded veterans housing program. Even after moving into her rental, White Bull knew that she eventually wanted to own a home.

One of the first barriers to homeownership many Native Americans living on South Dakota reservations have to overcome is a lack of knowledge about what it takes to be a homeowner. Banks and credit unions are few and far between in reservation communities, and many residents haven’t had the same exposure to banking or credit as non-Natives.

Several organizations are working to help Native Americans fill gaps in their knowledge of personal finance. One such organization is called the Oglala Sioux Tribe Partnership for Housing. The partnership has provided financial literacy and first-time homebuyer education courses to Pine Ridge residents for more than two decades. The organization’s efforts are bearing fruit, said Executive Director Emma Clifford.

“It is amazing to see the large number of younger people who are armed with a new weapon, and that’s a good credit report,” Clifford said. “They know what that can do for them.”

White Bull enrolled in financial literacy and first-time homebuyer classes taught by the partnership in 2016. Through the partnership, White Bull was able to enroll in a savings program that helped her put $4,500 into a bank account that could be used for the down payment on a house.

It took a couple of years for White Bull to build up her savings, establish her credit history and start looking for a home to buy. But she ran into a common problem.

“There are no homes for sale here,” White Bull said.

Nationwide, Native American reservations are severely short of adequate housing. In a 2017 U.S. Housing and Urban Development Department report, researchers found that reservations needed at least 68,000 more housing units to reduce overcrowding and replace older, dilapidated housing stock.

The housing shortage on reservations often forces Native Americans who want to own their homes to build one from scratch. On a reservation, building a home usually requires the future owner to install their water and septic systems and a line for electricity in addition to digging a foundation.

All told, building a home from scratch can add $30,000 to $60,000 to a home’s price. The extra expenses can prevent otherwise qualified buyers from getting a home, though there are programs that can reduce the costs, Vogel said.

“You really have to look at this whole big picture as to how can we promote and get more people into homeownership, and it takes multiple strategies happening at the same time to move this big issue,” Vogel said.

White Bull was able to build a home, and to do so, she needed help from a lender willing to make what many banks would consider a risky loan.

Alternative lenders fill gap

The banking system most Americans rely on for home loans is largely absent from South Dakota reservations. There are few, if any, traditional banks nearby, and mortgages for homes on tribally owned land require expertise that most lenders don’t have.

Instead, many Native Americans have looked to Community Development Financial Institutions such as Mazaska Owecaso Otipi Financial of Pine Ridge when they need a home or business loan. Community Development Financial Institutions are nonprofits that use grants and donations to fund loans and other financial services in underserved communities such as Native American Reservations.

Mazaska and similar organizations have been essential to providing people such as White Bull with the money to buy a home. Mazaska and similar institutions, however, have a limited pool of money to make loans. Generally, such groups rely on grants and donations to raise the money they lend.

Recently, Mazaska has been working with the U.S.Department of Agriculture Rural Development Office to make low-income home loans. The USDA gave Mazaska $800,000 and the organization raised another $200,000 for the effort. The $1 million has, so far, been used to issue eight home loans, said Colleen Steele, executive director for Mazaska.

“It’s been awesome,” Steele said of the USDA partnership.

Mazaska approved White Bull for a construction loan in 2018. She also qualified to use the South Dakota Governor’s House program. The state Housing Development Authority operates the program that sells affordable modular homes built by state prison inmates to low-income families and individuals. Prices for the homes range from $52,000 to $58,000.

In modular home construction, major components such as walls are mass produced at a central location and then assembled on foundations at individual home sites. The process keeps construction costs down and results in a more durable and valuable home than a mobile home.

It took nearly two years, but by the time COVID-19 struck the Pine Ridge Reservation in 2020, White Bull had a foundation ready for her new home. Thankfully, she said, home construction was one of the few activities tribal governments allowed to continue despite multiple lockdowns aimed at limiting coronavirus outbreaks.

By the end of summer 2020, the home White Bull had been working toward was ready. The pandemic, though, has kept her and her now 5-year-old grandson out of their new home.

“I have a 3-bedroom, 2-bath home,” White Bull said. “It’s sitting there all complete with electricity and water. I’m just waiting to sign the paperwork to close on it.”

“With homeownership, tribal families really have the opportunity to stay in their community, to be involved in and to participate in their cultures and their traditions, to pass their language on to their children and to just really be engaged at the community level." -- Casey Lozar, director of the Center for Indian Country Development at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank

Paperwork problems slow process

Another issue Native American home buyers on reservations face comes down to paperwork. Most of the land within reservation borders is held in trust and managed by either the Bureau of Indian Affairs or the tribal government.

If someone wants to build or buy a home on trust land, they first must secure permission from their tribal government. Then they need to get as many as three different title status reports for the plot of land the house will sit on from the BIA, tribal government or both. Title status reports are the official record of how a piece of tribal land has been used in the past.

Before COVID-19, securing a title status report could take months depending on which agency was processing an application. Outside of reservations, the typical mortgage loan takes between 30 and 45 days to finalize.

Often, the speed with which an application for a title status report is processed depends on how closely a lender is able to work with local BIA or tribal land offices. The need for a close relationship is another reason large banks tend to shy away from lending to reservation residents.

Potential solutions to the paperwork problem could be passing a federal law that requires the BIA to meet a specific deadline when processing a title status report application, creating an online portal for title status report applications and sharing best practices between agencies and offices, Lozar said.

“It really comes down to outdated systems that the BIA has, a lack of efficiencies and accountability to make sure that the bureau is following through with turnaround times,” Lozar said.

Some progress had been made on speeding title status report processing, but the pandemic forced land offices to close and, in some cases, stopped the processing of paperwork altogether. Steele said some homebuyers have had to wait up to nine months for a certified title status report during the pandemic. Before COVID-19, the wait for a report had been about three weeks.

On Jan. 4, White Bull said she had been waiting four months while the tribal offices processed the paperwork needed to finalize her loan, and she doesn’t know when she’ll be able to move into her new home.

Still, White Bull said she looks forward to planting grass and a garden in her yard and, one day, to giving the home to her children and grandchildren.

“This gives me a lot of peace and serenity,” White Bull said. “There’s no more worry. As long as I keep my payments up, I’ll be good.”