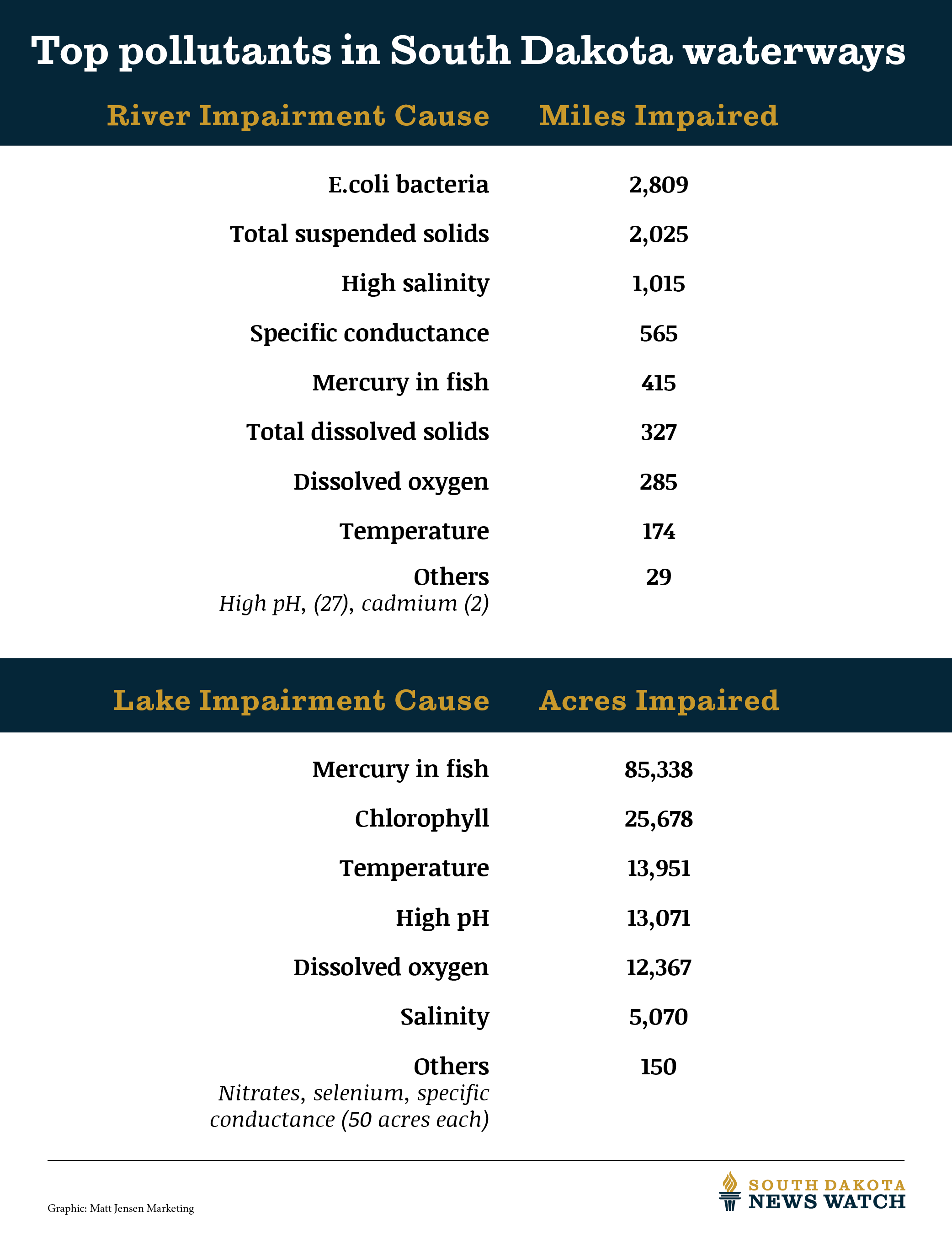

The state of South Dakota, its cities and industries have spent hundreds of millions of dollars to treat wastewater over the past decade, and yet highly toxic chemicals including mercury, cyanide, cadmium, hydrogen sulfide and ammonia have made it into state rivers.

Despite the heavy investment and multi-million-dollar annual cost of pollution removal, federal data from fiscal 2017 shows that 127 South Dakota treatment systems were in non-compliance with federal pollution standards and that 62 serious violations and 85 enforcement actions were issued statewide.

Meanwhile, as South Dakota’s population grows, and industry and agriculture expand, pollution control records show that the state has done a progressively worse job in recent years of protecting its rivers from pollution, according to a South Dakota News Watch analysis.

State inspections of municipal and industrial facilities with permits to dump pollution in South Dakota rivers or wetlands have fallen by nearly half in the past five years, from 158 inspections in 2013 to only 80 in 2017.

When state inspections are done, violations are commonly discovered, ranging from data recording errors to exceedances of limits on toxic chemicals and nutrients.

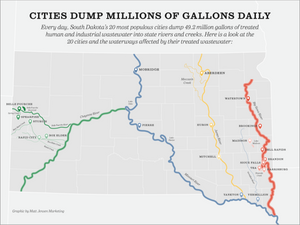

A South Dakota News Watch permit analysis showed that cities and industries dump about 19 billion gallons of treated wastewater into state rivers each year. Records show that cities and companies have had pollution releases beyond acceptable limits for a host of toxic chemicals and bacteria during the past decade, making some rivers unsafe at times for humans, fish and wildlife.

The slowdown in inspections has dovetailed with an inability by the state to keep permits and pollution limits for dischargers up to date.

As of mid-August, 121 surface water discharge permits were considered “administratively continued” in South Dakota, meaning the parameters of facility operations and pollution limits have not been updated in the past five years or more. Of those outdated permits, some permits have not been revised in nearly two decades, including at two of the state’s biggest and most complex wastewater facilities: the permit for the city of Sioux Falls last renewed in June, 2000 and the permit for the Smithfield Foods plant in Sioux Falls last renewed in March, 2000.

Since the permit for the city of Sioux Falls was last updated in 2000, the city’s population has risen by almost 40 percent. Of the state’s 20 most populous cities, half are operating wastewater treatment facilities on lapsed permits. South Dakota is behind the national average and most neighboring states in terms of keeping discharge permits renewed, federal data show.

Albert Spangler, the engineering manager who oversees the state’s permit inspection program within the Department of Environment and Natural Resources, acknowledges that lapsed permits are not good for the environment.

“It doesn’t account for changes since then, and the biggest thing is, did the water quality standards change between then and now?” Spangler said, adding that some water quality standards are typically updated about every three years.

Spangler has said that staffing issues have led to fewer inspections and updated permits. Spangler said his team has added people this year and is now fully staffed to increase efforts to oversee wastewater processes in South Dakota.

Pollution limit violations are not uncommon

Regulation and enforcement of permit holders requires constant diligence and scrutiny in order to protect river quality and human health, said Steve Meyer, executive vice president and general manager for Brookings Municipal Utilities.

In an unusual municipal regulatory role, Meyer oversees a system that treats city wastewater but also monitors and enforces pollution standards for several major industries, including food and medical processors, metalworking firms and a 3M plant in Brookings.

Meyer has had to act as an enforcer several times, including in 2014 when the city issued $41,000 in assessments to Sterling Industries, the maker of human and veterinary medical products, for a series of violations of acidity limits in its wastewater. Meyer also issued violations to the Bel Brands cheese plant that same year after the company released potentially explosive levels of hydrogen sulfide gas that also could have killed city workers who inhaled it and corroded treatment systems.

“They’ve got the hydrogen sulfide issue under control, but we are under constant risk from that so we continue to monitor that closely,” Meyer said.

Regulation of local employers is not easy and can sometimes be confrontational, but Meyer said he upholds state and federal laws and eventually gets compliance from local dischargers. “I would have to call them all success stories at this current time, but who knows what’s going to happen tomorrow,” Meyer said. “I will give them all credit for spending the money and changing procedures or installing equipment, so whatever they’ve had to do, they’ve done it.”

After inspections, municipal and industrial discharge permit holders are routinely given violations for exceeding pollution limits in wastewater and requirements that they fix problems and update the state on progress.

The Wharf Resources gold mine near Lead has had a number of violations over the past decade, including for releases of mercury, cyanide, cadmium and nitrates. Recent inspections have improved for the mining company that discharges wastewater into Deadwood Creek and a number of small waterways that flow into Spearfish Creek.

In 2014-2015, the Dakota Provisions turkey plant in Huron violated limits for oil and grease discharges on 27 occasions and its pet food subsidiary DaPro had five similar violations during that time.

The South Dakota Soybean Processors plant in Volga was flagged in 2017 for violating discharge limits of oil and grease, total suspended solids and pH as well as for failing to sample wastewater as often as required.

On Aug. 15, the Smithfield Foods plant in downtown Sioux Falls – which dumps about 2.5 million gallons of wastewater into the Big Sioux River each day – reported a treatment system breakdown that led to the release of ammonia above state pollution limits. State officials said there was no risk to humans though fish in the river could be threatened. State inspectors went to the plant for further testing and worked with company employees to fix the problem.

Industries are taking steps to improve their processes and wastewater quality, often at great expense.

In the mid-2000s, the Valley Queen Cheese Factory in Milbank was a consistent violator of pollution standards, with 1,002 violations in a 3-year period and numerous violations since. Officials at the plant, which has 250 employees and processes 1.5 billion pounds of milk into cheese each year, spent $3.5 million to build a wastewater treatment plant in 2005. They have invested $6.5 million since then on upgrades, according to an email sent to News Watch. “We are committed to protecting the environment in which we work and live for future generations,” CEO Doug Wilke wrote.

City wastewater systems have had problems

South Dakota municipal systems, often just breaking even financially, have also had a variety of problems over the years.

The city of Flandreau has had difficulty meeting effluent limits, with 11 violations in 2013-14, including emergency discharges of wastewater that were never reported to the state and numerous reporting lapses or errors.

The city of White had a string of violations for total suspended solids, fecal coliform, biological oxygen demand and ammonia between 2007 and 2015.

In Mobridge, state inspectors found violations for total coliform and E.coli in recent years, and in 2015 an inspector found a leaking lift station that no one from the city was aware of.

Not all wastewater issues, however, are related to mechanical breakdowns.

In the early 1990s, two employees of the John Morell plant in Sioux Falls (now Smithfield Foods) were convicted of falsifying testing data regarding the release of ammonia from the plant.

In 2015, the former superintendent of the Pierre Wastewater Treatment Facility was indicted and pleaded guilty to charges he falsified reports on the release of chlorine from the plant that dumps into Lake Sharpe on the Missouri River.

The Pierre system has had other pollution violations in recent years, though new Superintendent Nathan McCombs said the state and city have worked to improve the facility and straighten out sampling and recording issues.

McCombs said Pierre obtained a $5 million low-interest loan from the state revolving loan fund to install an ultraviolet light bacteria treatment system that eliminates the need for chlorine, and has the money to upgrade the system headworks and biosolid handling equipment in future years. “It [the UV system] works awesome and we make good water here now,” McCombs said.

The state spends significant money to help cities and counties improve water quality.

Spangler pointed to the small city of Sinai in Brookings County as a recent success story. The city of 120 people has an outdated treatment system that racked up dozens of violations in recent years.

Records show the state has allocated $1.5 million to build a new system for the town. The State Water Facilities Plan shows that $323 million in proposed projects were fully or partially funded by the state in 2018. Another 173 projects on the list with a potential price tag of $221 million did not receive any money.

Nationally, 28,700 of the roughly 300,000 permitted dischargers were in non-compliance with federal pollution standards, according to the EPA, and there were about 10,000 serious violations of discharge limits in fiscal 2017, the agency said.

Even with pollution limits in place, South Dakota rivers suffer long-term, often unseen degradation from the constant onslaught of wastewater dumped into them, said Jay Gilbertson, director of the East Dakota Water Development District.

“It’s an accumulation. Operating under the auspices of a discharge permit, you’re adding a certain amount of pollutants to the water,” Gilbertson said. “Technically, they may be below the [pollution] limit, but if everybody discharges at just below the limit, you’re going to get to the limit pretty quick.”

One poorly understood drawback of modern wastewater treatment systems is that they may inadvertently be a crucible for the creation of new, potentially dangerous compounds that wouldn’t exist on their own.

“What makes a wastewater treatment plant unique is that it’s taking in all sorts of waste and mixing it all together, and that unfortunately provides breeding grounds for these potentially dangerous bacteria,” said Kelsey Murray, who as a South Dakota School of Mines & Technology researcher found genetic markers for dangerous shigatoxigenic E.coli in Rapid Creek and the Big Sioux River last year. “It’s when we start mixing these fecal bacteria that in the past would have never met each other, and now we’re stirring them up and they’re able to exchange their genes and then we’re sort of creating this perfect storm to create a potential human pathogen.”

‘I guess it’s just not a recreational river’

Kim Schmidt and her family have a shoreline view of the abuse laid upon one South Dakota river.

Schmidt, her husband and adult daughter live in the first home downstream – and often downwind — of the Rapid City Water Reclamation Facility located a few miles east of Rapid City.

Schmidt said the treatment plant, which dumps about 12.2 million gallons of treated wastewater into Rapid Creek each day and is visible from her porch, can be a burden on her quality of life.

When the weather allows for open windows at night, Schmidt said, the odors from the plant “will wake you from a dead sleep.”

The Schmidts, whose home is nearly encircled by a bend in the creek, are subjected to two of the most damaging forms of river pollution in South Dakota: the smell and discharges from the sewage treatment plant but also the barrage of garbage and urban runoff that flow into the creek as it passes through a city of 75,000 people. Schmidt said she sees household wastes, litter and sometimes used drug paraphernalia including syringes floating in the creek.

Schmidt said she occasionally kayaks on the creek or goes into the water to manage weeds on the shoreline, but always takes a shower shortly after.

“I know it’s nasty, and everybody has concerns, but truthfully what are you going to do?” she said. “I guess it’s just not a recreational river.”

The discharge from the Rapid City plant almost always meets state and federal pollution limits, system superintendent Dave Van Cleave said.

Van Cleave takes great pride in the system he oversees, which he said removes more than 95 percent of the pollutants that enter the plant.

“I think the wastewater treatment industry and ours in particular does a pretty good job of leaving the stream in a condition that is usable and safe for people,” said Van Cleave, who is looking forward to $62 million in proposed plant improvements over the coming years. “With the level of technology we’re at, we’re removing the bulk of it. Is there more work to do, yes there is, and the rivers can always be a little cleaner.”

Water quality standards and permit parameters for direct, or “point source” polluters were mandated as part of the federal Clean Water Act of 1972; South Dakota assumed authority over the permit system in 1993.

"It's an accumulation. Operating under the auspices of a discharge permit, you're adding a certain amount of pollutants to the water. Technically, they may be below the (pollution) limit, but if everybody discharges at just below the limit, you're going to get to the limit pretty quick." – Jay Gilbertson, director of the East Dakota Water Development District.

Working to make things better

On a basic level, wastewater from cities and industries is treated and discharged in a few ways. Most industries and some cities have pre-treatment programs that use chemicals and mechanical processes to remove or counteract pollutants prior to the water being treated at more traditional municipal or industrial facilities.

Most cities collect sewage and treat it with physical barriers such as screens and settlement tanks and also with living microbes that consume nutrients and other pollutants. Smaller cities use lagoons to settle the wastes before discharging wastewater into manufactured wetlands or creek tributaries; some systems discharge only intermittently or not at all. Larger cities that generate too much wastewater for lagoons use mechanical treatment systems with screens, microbes, natural filtering processes and ultraviolet light before discharging treated water directly into rivers. There is no discharge allowed to lakes.

Treatment system operators are required by the state and federal government to capture and test water discharges on a daily and or monthly basis. Samples are sent to state or private labs for testing, and results are then shared with system operators and finally officials within the state DENR.

Some pollutants that make it past an industrial pre-treatment process or enter through households or sewer drains are likely to make their way into rivers. Household chemicals, pharmaceuticals or oil and grease are not typically trapped or fully treated by traditional wastewater processes.

“If there are some other dangerous chemicals that we’re not looking for, it’s because the EPA and the DENR have not listed those for us to eliminate,” said Meyer of Brookings.

The state may tailor testing requirements to a certain city or plant depending on what comes into the system and the nature of the destination waterway, Spangler said.

For instance, the POET Biorefining ethanol plant in Mitchell met all state permit requirements for wastewater in 2015. But the state did not specifically test wastewater for the 28 substances on the approved chemicals list for use at POET that includes toxic materials such as hydrochloric acid, sulfuric acid and sodium hydroxide. The state says those substances are unlikely to affect river water quality if the company follows chemical manufacturer directions.

When a pollution violation or an accident occurs, such as the high ammonia releases from the Smithfield Foods plant in August, there is no way to recover those chemicals from state waterways.

Investing in better treatment plants or new processes and limiting use of chemicals by industry are ways to reduce pollution in South Dakota rivers, though educating residents to be more careful and conscientious about what they dump down the drain or allow to ooze into sewer grates is another big step.

Advocates also see public education and grass-roots pressure as a way to increase accountability of industry and the government agencies who monitor their compliance.

“People need to not only have information but to use it by talking to their city, county, state and federal representatives and bureaucratic agents and making sure they know that we want clean water, and we want it maintained and that they need to do something about that,” said Lilias Jarding of the Black Hills Clean Water Alliance.

Jarding also called on the state legislature to increase funding for the DENR to add staff and resources to enhance the regulatory process.

Some water experts such as Gilbertson have also called for stronger regulation of pollutant releases over time, and he suggests that more inspections and fines may prompt polluters to do better.

Despite problems due to human error or mechanical breakdown, South Dakota treatment plant operators say they are committed to protecting water quality and the public.

“The quality level of the effluent we put out here is excellent compared to what permitted parameters are, and we don’t want to be bumping up against those and having compliance issues – we just don’t want to be there,” said Mark Perry, superintendent of the Sioux Falls Water Reclamation Facility.

Perry, who said he wouldn’t feel comfortable at this time swimming or fishing in the Big Sioux River, said he and other operators will continue to seek the best technology and processes to help and not hurt rivers over time.

“We’ll get there,” Perry said. “It took a long time to get where we’re at, and you can’t turn this around overnight.”