Both not wearing a seatbelt and texting behind the wheel are illegal in South Dakota. But when lawmakers passed those laws, they specifically included language making them secondary offenses, meaning officers must have another reason to pull over a violator.

Texting and driving is widely recognized as a growing safety concern and, like many other states, South Dakota is grappling with how to crack down on the practice. The state spends about $1 million in federal funds a year to promote seatbelt use and fight distracted driving.

But, generally, lawmakers have been slow to adopt new highway safety laws or to empower law enforcement officers to enforce laws on the books. The historic reluctance by South Dakota lawmakers to pass highway safety legislation stems from a long-standing disdain of government oversight of their lives, doubts about the validity of government statistical data, and a feeling that South Dakotans can be trusted to make good decisions on their own.

As in the past, some lawmakers offered two measures this legislative session to strengthen seatbelt and texting laws. Separate House bills would have redefined texting while driving and seatbelt use as primary offenses, and raised the penalties.

As usual, the seatbelt measure died in its first committee hearing. Despite passage in the House, the texting while driving bill was killed in the Senate Judiciary Committee on a 5-2 vote. Opponents argued that police could have stopped cars just because an officer saw something in the driver’s hand. During testimony, Hawley called the texting situation a “crisis” in South Dakota

The lax nature of South Dakota highway safety laws has allowed for some unusual — and unsafe— occurrences on state roadways.

- While on patrol, Aberdeen Police Chief David McNeil saw a man drive by in a Chevy Chevette with his pet mountain lion in the passenger seat.

- State Rep. Spencer Hawley of Brookings was cruising at 80 mph on Interstate 90 recently when a woman passed him with her knees on the steering wheel while she had a sign-language conversation on an iPad lodged atop the dashboard.

- Lee Axdahl, director of the South Dakota Office of Highway Safety, was at a stoplight in Pierre when he saw a woman texting intently behind the wheel while two unbelted children frolicked in the back seat. When the light turned green, the woman pulled forward without raising her eyes from her phone.

“She didn’t look to the left; she didn’t look to the right. She didn’t do anything,” said Axdahl.

Other states have tougher highway laws

South Dakota lawmakers generally have been slow to act compared to other states.

Among the 49 states with a mandatory seat belt law, South Dakota was the last to enact its law in 1995, a decade after many other states. The only state without a seat belt law is New Hampshire. Meanwhile, South Dakota remains second to last in seat belt usage among all states and U.S. territories, ahead of only New Hampshire.

In 2016, the national average of belted drivers was 90.1 percent, compared to only 74.2 percent in South Dakota, according to the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration.

Several South Dakota cities grew tired of waiting for state lawmakers to pass a primary texting law and passed their own municipal laws to crack down on texting behind the wheel. Among them are Sioux Falls, Rapid City, Mitchell, Aberdeen, Brookings, Watertown, Vermillion, Huron and Box Elder.

"She didn’t look to the left; she didn’t look to the right. She didn’t do anything.” – Lee Axdahl

Lawmakers passed a statewide texting-while-driving ban in 2014 after attempts in prior years failed. Even then, opponents pushed to enact a ban as a secondary offense and to override the municipal laws making it a primary offense. Eventually, the statewide ban passed as a secondary offense and the municipal ordinances remained intact.

South Dakota came in last in a recent nationwide highway safety study. The state had only two of 16 traffic safety laws in the latest legislative report card released by the Advocates for Highway and Auto Safety, a national group committed to improving highway safety. Wyoming rated second-worst, with three of the laws in place; the top state, Rhode Island, has 13 of the 16 tracked laws in place.

The 2018 Roadmap of State Highway Safety Laws report notes that, among other things, the state doesn’t mandate use of motorcycle helmets. South Dakota does not require that child safety seats be rear-facing until a child turns 2. South Dakota also allows 14-year-olds to get a driver’s license, while many states force drivers to wait until 16.

In addition, South Dakota is one of only four states that does not make texting while driving a primary offense, and that the state is among 16 that do not make seat belt use a primary offense.

“Until something becomes a primary law, I don’t think people recognize that it’s something significant that they should pay attention to and obey,” said Marilyn Buskohl, a government affairs specialist with the American Automobile Association in South Dakota.

‘You don’t put your seat belt on to go check the cows’

Sentiments against more stringent highway safety measures were immediately clear during a recent visit to the Black Hills Stock Show in Rapid City. While most of the dozen people interviewed were in favor of stronger texting-while-driving laws, support for a primary seat belt law was hard to find.

Steve Larson of Hayti runs a farm and drives a truck on the side. He said it isn’t the government’s business whether he wears a seat belt or not. “I hate them; have never worn them,” said Larson, 61.

Marlyn Haiwick, 71, a retiree from Whitewood who used to farm near Highmore, said he supports a primary seat belt law but wouldn’t obey it if it passes. He said the only time he wears a belt is when he sees an officer ahead, and even then he just pretends to put it on by quickly pulling the shoulder belt across his body.

“You don’t put your seat belt on to go check the cows, you just don’t,” Haiwick said. “We never got used to seat belts, we just never have. Some of these old boys, they aren’t going to wear a seat belt or a helmet no matter what you do.”

Many of the historic arguments against new highway safety laws arose during debate in the House of Representatives Judiciary Committee on Feb. 7, where lawmakers considered bills to make texting while driving and seat belt use primary offenses and to raise the penalties for violations.

Rep. Hawley, a Democrat who is lead sponsor of both measures, said he proposed the seat belt measure after riding along with a highway patrol trooper who spoke of responding to fatal crashes where seat belts were not used. Many of the victims were ejected from their vehicles and killed, Hawley said.

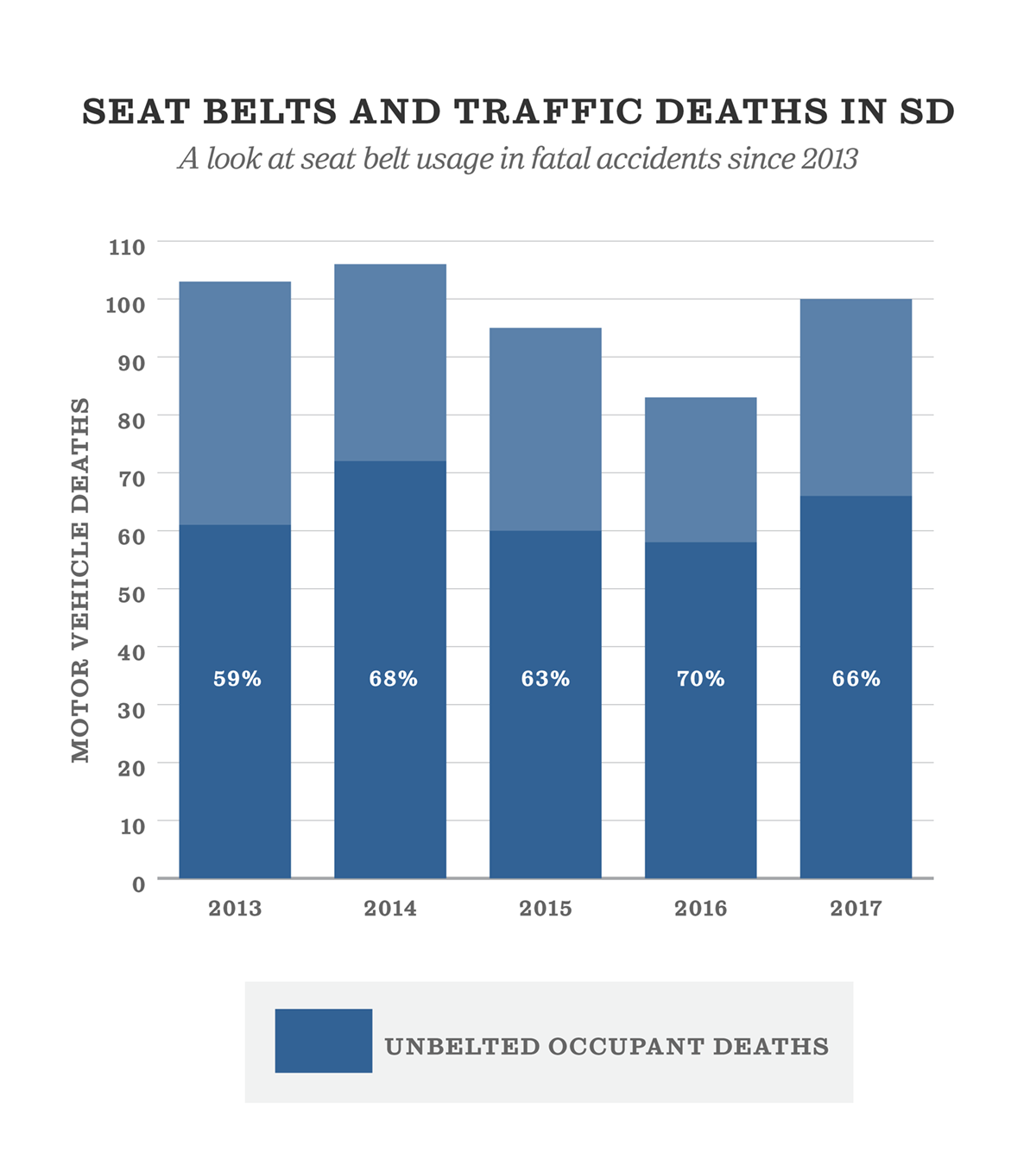

Hawley also cited statistics that he said show seat belts save lives. He noted that in South Dakota in 2017, 66 of the 100 fatalities in motor vehicle accidents were people who were not wearing seat belts and that injuries were reduced in crashes where seat belts were used.

Backers of the bill said primary seat belt laws lead to greater use of seat belts, a concept supported by the National Highway Traffic Safety Administration, which said in a 2011 report that, “Jurisdictions with stronger seat belt enforcement laws continue to exhibit generally higher use rates than those with weaker laws.”

Insurance industry lobbyists argued that accidents involving unbelted occupants cause millions more in damages and hospital bills each year, and that those costs are then passed on to all insured consumers. A few people told personal stories about unbelted drivers who were ejected and died and about belted drivers who survived.

But for each of those arguments, opponents who testified said essentially the opposite. Flandreau attorney Bob Pesall, who has fought stricter seat belt laws in South Dakota for years, crystalized one of the historical arguments against stronger highway safety laws.

“I do not believe it is the appropriate role of government to reach into a car and tell a law-abiding adult what to do,” Pesall said.

Testifying by phone, Pesall told how his elderly uncle burned to death in a crash because he wore his seat belt and was unable to get out. Pesall also pointed to data that he said show that primary seat belt laws do not reduce fatalities.

Axdahl, however, takes great issue with the notion that wearing a seat belt can make a vehicle occupant less safe and refers to that claim as “an urban legend.”

Axdahl said vehicle manufacturers have gone to great lengths to strengthen passenger compartments to make the inside of a vehicle the safest place in a crash. “It’s not the people who are belted who are dying in these crashes,” Axdahl said. “Anyone who tells you they would be safer being thrown 100 or 150 feet — you just can’t deny the laws of physics.”

The state contracts with Sioux Falls advertising agency Lawrence and Schiller to produce public-service campaigns to encourage seat belt use. Two seat belt safety commercials aired regionally during the Super Bowl featuring “Jim Reaper,” a character based on the grim reaper.

In an interview prior to the House committee hearing, Gov. Dennis Daugaard said he was “skeptical” that either the seat belt or texting measure would pass the House and Senate. “South Dakotans have the feeling that they should be free to decide” whether to buckle up or text, Daugaard said. The governor said if the bills do pass, he would consider signing them.

Texting ban gaining some momentum

However, with so many outrageous examples of drivers who are distracted due to text messaging, the texting measure had strong support during the House hearing.

During testimony, Sen. Larry Tidemann, a Brookings Republican who is the lead senate sponsor of the bill, shared his own harrowing texting tale.

While driving 80 mph on Interstate 29, a woman drove by Tidemann in the left lane while eating with one hand, texting with the other, and using her feet to hold the steering wheel.

No one testified in opposition to the measure that would make texting while driving a statewide primary offense and raise the penalty from $100 to a Class II misdemeanor and a fine up to $500. Hawley said the fine for texting would typically be the same as a speeding ticket.

“You always hear about it, and you think it’s never going to be you, and it could be you.” Justin Iburg

A look at the many government reports on distracted driving leaves little doubt that sending or reading text messages while driving is dangerous.

According to the NHTSA, 3,477 people died and 391,000 were injured in crashes in the U.S. in 2015 in which distracted driving was a cause. Texting behind the wheel, the agency said, makes a crash 23 times more likely.

The problem is even more acute among younger drivers. An AT&T teen driver survey showed that 97 percent of teens agree texting while driving is dangerous, but that 43 percent do it anyway. Data from the Centers for Disease Control show that drivers under 20 have the highest proportion of distracted driving deaths. The CDC also reports that teens who admit to texting while driving are also less likely to wear a seat belt, more likely to ride with a driver who had been drinking and more likely to drink and drive themselves.

Due in part to outdated reporting forms, South Dakota does not have solid texting-while-driving statistics. Axdahl said his department is working on improvements that will allow for more accurate recording of data.

Seven years after he caused a fatal accident while texting and driving, Justin Iburg of Mitchell is still haunted by the wreck. Iburg, then 20, took his eyes off the road for five seconds in September, 2010, to check a text message while driving in a construction zone. Iburg slammed into a motorcycle driven by 44-year-old Jon Christensen, who was thrown from his bike and killed. Iburg was acquitted of manslaughter, but convicted of reckless driving and spent several weeks in jail.

As part of his sentence, Iburg agreed to give public presentations on the dangers of distracted driving and made 54 appearances. He said he supports making texting while driving a primary offense.

“There’s a lot of consequences, so it’s just not worth doing it,” Iburg said in an interview. “You always hear about it, and you think it’s never going to be you, and it could be you.”

One hurdle to preventing young drivers from texting behind the wheel is that they all think they are experts and can do it safely, Axdahl said. “They think everybody else is bad at it except me,” he said. “How do we convince drivers that, ‘Yeah, everybody is really bad at it, including you?’’

One of the most frequent arguments against texting-while-driving laws is that they are difficult to enforce, especially since it is legal to use a cell phone in a car to make or receive voice calls.

But in Aberdeen, one of the first cities to make texting while driving a primary offense, Chief McNeil advises his officers to use common sense when making a traffic stop.

“I give officers discretion,” McNeil said. “I tell officers, if it’s there and things match up, then go with a ticket. But if someone tells you they were trying to make a phone call, believe them and give them a warning and let them know how they can be safer.”

As a result, officers in Aberdeen have written few tickets for texting while driving. According to the department’s annual reports, officers from 2013-16 issued seven written warnings and wrote 11 tickets. In Rapid City, officers wrote nine texting citations in 2014, according to department spokesman Brendyn Medina.

McNeil said he believes the roadways in Aberdeen are safer as a result of the city’s primary texting ordinance. To make people aware of the law, McNeil has conducted exercises where spotters watch traffic for texting drivers and alert officers down the road who to stop. Drivers are then warned that they were behaving unsafely.

Giving verbal warnings, McNeil said, has made a positive effect on driver behavior. “We don’t have the time or resources to take the phone out of somebody’s hand and do a forensic analysis on it,” he said. “But let’s face it, a regular citizen who has a phone in their hand and is pulled over, it’s not a pleasant experience. It’s inconvenient, and for a lot of people, that is the stimulator to get them to think and be more hesitant to use their phone next time.”