As the property tax takes a larger share of their incomes — and at a time when many are hurting financially — South Dakota farmers and ranchers are pushing for reform of the state’s system of valuing and taxing their lands.

But as a decade-long process of updating the system nears an end, it has become increasingly clear that any reform effort that aids agriculture producers will lead to higher taxes for residential and commercial property owners who will assume a larger burden of paying for education and county services.

When legislators overhauled the state’s system for assessing the taxable value of farm and ranch land in 2008, the idea was to make the system more fair and ensure tax rates better reflect just how valuable ag land is in a given year. The reform led to sharp increases in ag land values and property tax bills rose accordingly. But as commodity prices have tumbled in recent years, profits have shrunk and taxes are taking up an increasing portion of farm and ranch incomes. Now, as the number of farm bankruptcies and the suicides rate among ag producers continue to rise, many are calling for new reforms in the state’s property tax system.

“That gets to the urgency here. We need a fix,” said Gary Deering, president of the South Dakota Stock Growers Association.

Ranchers have been hit hard by the state’s property tax system which assigns taxable value based on an acre of land’s highest and best use, not its actual use. That has led to claims that some rural landowners are paying unfairly high taxes on land that isn’t producing revenues at a time they can afford it least.

“You could have some areas in South Dakota that are virgin sod but because of the soil type, they’re being taxed as if it were tillable ground and most tillable ground, at least in my area, is being taxed at two-and-a-half times the rate of pasture ground,” said Jim Peterson, a former legislator and current East River farmer who has worked on the property tax issue for 14 years.

Critics say the current tax system adds to the pressure on farmers and ranchers to plow up grasslands which perform essential environmental functions, such as preventing erosion. Grasslands also provide habitat for game animals such as pheasants, which are a big driver of the state’s second largest industry — tourism.

“It’s almost totally the opposite of the way we should be doing it for non-cropland,” said Angela Ehlers, executive director of the South Dakota Association of Conservation Districts.

The state legislative Ag Land Assessment Task Force, created about 10 years ago to oversee changes to the property-tax system, is trying to find the solution Deering and his fellow ranchers say they need. On Oct. 24, the task force held its first meeting of 2019 at the Capitol in Pierre. The centerpiece of the meeting was a presentation from the state Department of Revenue about a pilot study that looked at what impact two entirely new property tax systems — one that would use computer software to determine what the most probable uses for farm and ranch lands is each year, and one that would look at what the land is actually being used for each year — would have on 11 counties spread throughout the state.

Under both systems, the study found, total valuation for farm and ranch land in the 11 counties would decrease by more than $1 million. Under the actual use model, valuation fell by more than $2 million in the 11 counties that were studied. If used statewide, the loss in property valuation could result in a shift of the tax burden away from agriculture and toward homeowners and commercial property owners, said Wendy Semmler of the DOR property tax office.

She said the pain likely would be felt most in school districts that have taken out loans to pay for new buildings or necessary renovations. Those districts may have to raise tax rates on residences and businesses to make up for reduced ag land values, she said.

“If we are going to see extreme value decreases in any particular school district, that is going to cause the levies to increase,” Semmler said.

The tax burden, though, has already shifted toward farmers and ranchers, said Peterson, a member of the Ag Land Assessment Task Force said. While residential and commercial property values have risen by about 20% statewide, he said, the values on ag land have risen up to 200% in some areas over the past decade.

“We’ve taken a lot of skin and put it into the game from agriculture,” Peterson said.

Seeking a more equitable system

Historically, ag land property tax rates in South Dakota were determined using data on recent, comparable land sales. Usually, that system worked out in favor of farmers and ranchers, who despite owning the lion’s share of property in the state have historically paid less in property taxes than commercial property owners and homeowners.

In the mid-2000s, high crop prices, strong hunting tourism and increased development on city edges caused land sale prices to skyrocket. At the time, any land sale that wound up being 150% or more of the historical average couldn’t be used to assess taxable value. The problem was, Peterson said, just about every time land was sold in the waning years of the past decade, the price wound up being more than 150% of the historical average. Agriculture lands would either be undervalued or would see their value rise exponentially from one year to the next. Neither situation was tenable.

During the summer of 2007 and in the 2008 legislative session, state lawmakers hammered out the details of a new system for assessing ag land valuation. It went into effect in 2010 and 2011 was the first year in which taxes calculated using the new system were paid. It has remained in place relatively unchanged ever since.

Under the current system, ag land property taxes are calculated using what is known as “production valuation.” Essentially, the state Department of Revenue works with economists at South Dakota State University to determine the highest revenue potential each year for both cropland and non-cropland, and then provides that number to county equalizers. The equalizers use state-approved soil tables to calculate the taxable value of each acre on a given property. Once the taxable value is calculated, equalizers can adjust the value based on such things as how difficult a parcel might be for farm equipment to access or its potential for crop growth before assessing the actual tax bill.

The system has led to farmers and ranchers taking on a larger share of the state’s property tax burden.

According to the DOR, farmers and ranchers saw their share of the state property tax burden rise from just under 25% to about 28% between 2008 and 2018. In real dollars, the state’s farmers and ranchers saw their collective property tax bill rise from $219.7 million in 2008 to about $354.6 million in 2017. Commercial properties meanwhile have seen their share of the state property tax burden fall from about 31% in 2008 to about 29% in 2018. Homeowners’ share of the burden has remained essentially flat at about 39%.

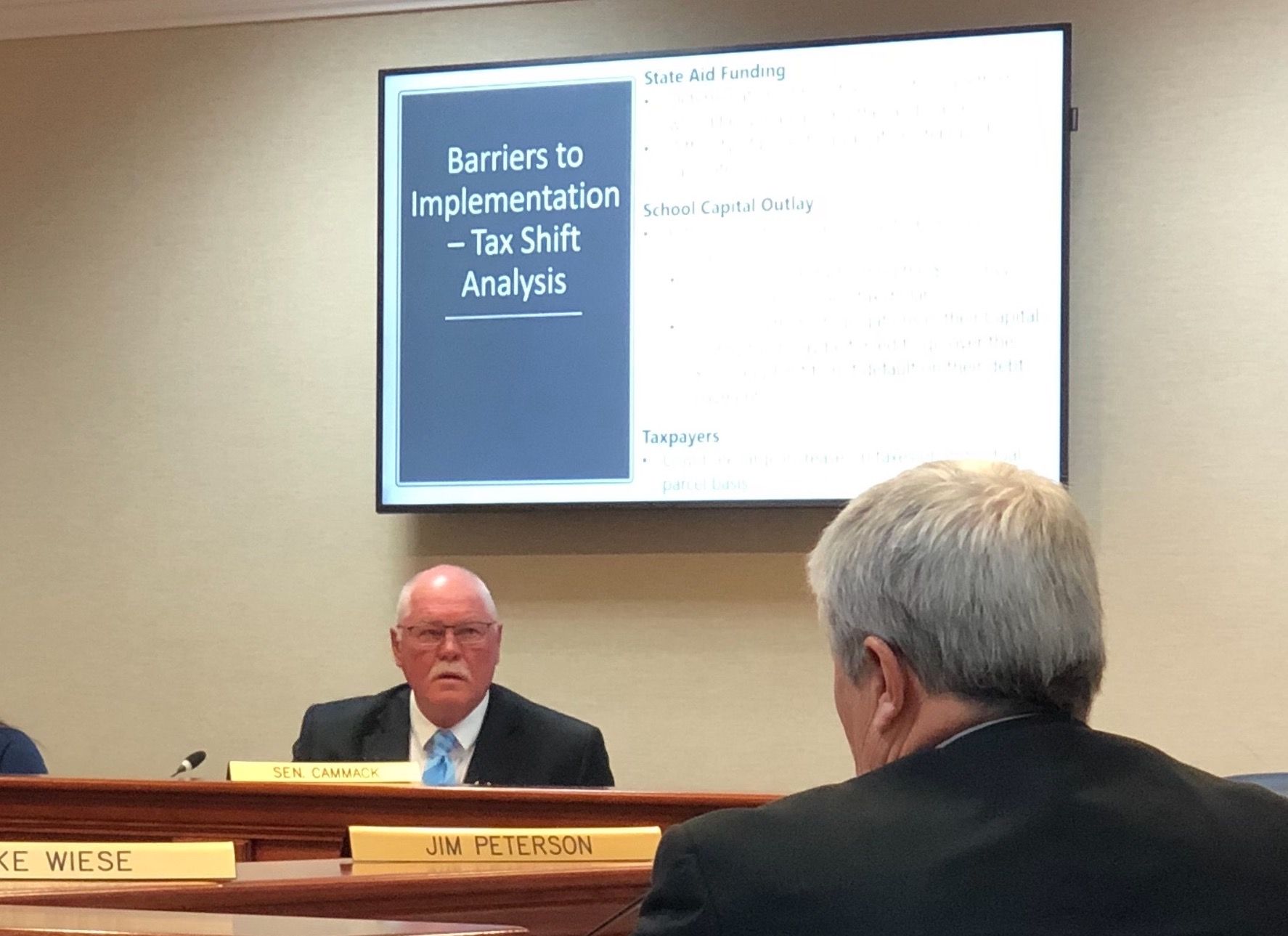

The problem for farmers and ranchers right now is that their taxes are being calculated using average crop prices from years that saw historically high prices, while the current prices for such things as corn, soybeans and beef are relatively low. Eventually, those high-price years will be worked out of the system. But in the meantime, taxes are taking up a much larger portion of farm and ranch incomes, said state Sen. Gary Cammack, R-Union Center, a rancher and business owner who chairs the Ag Land Assessment Task Force.

“We certainly expect to pay our fair share,” said Cammack. “But we also don’t want it to be such a heavy load that it starts to create some hardships.”

Not great for grass

Ranchers have been particularly hard hit by the current property tax system. It relies almost entirely on soil tables to determine whether a piece of land is cropland or non-cropland in order to make value determinations a bit more objective. But the system doesn’t account for value that goes beyond dollars and cents.

Many acres of crop-rated soils currently are covered in unbroken, mostly native prairie grasses, Cammack said. Those native prairie remnants support a diverse range of birds, bugs, plants and animals, all of which have non-monetary value, he said. Native prairies also happen to be one of North America’s most endangered ecosystems.

“We don’t want to lose that,” Cammack said.

Cattle can and do co-exist with most prairie species while providing an income to the landowner — it’s just lower on a per-acre basis than growing corn or soybeans. But crop-rated soil, whether it is growing prairie grass or a cash crop, often is taxed as if it were growing corn.

Deering, who ranches in Meade County about 35 miles east of Sturgis, said most West River ranchers simply cannot afford to buy the equipment necessary to plant the relatively few acres of their land that are home to crop-rated soils. For the better part of a decade, he and many other ranchers have been forced to eat the cost of higher tax rates without the benefit of growing any high-dollar cash crops.

“There’s not much else you can do,” Deering said. “I’d probably go broke if I had to buy farm equipment.”

Covering the higher property tax rate wasn’t that big an issue early on. In 2014 and into 2015, cattle prices were relatively high. But since 2016, cattle prices have fallen and it is getting harder to make ends meet, Deering said.

“The consequence of this system is that the grazing guys are carrying some of the burden of the corn and bean guys,” Deering said.

Farmers, though, can benefit from the tax system even when crop prices are low. If a farmer has non-crop rated soil on their land but plants and harvests a marketable crop from it, not only does that farmer pay a lower rate on the land, they can collect that much more profit from it, too.

Deering said the state’s current property tax system ends up creating an unintentional incentive for landowners to till up grassland that previously had not been touched by the plow.

Ehlers, with the Association of Conservation districts, said wayward topsoil carried out of tilled farm fields by wind and rain is one of the leading causes of pollution of lakes and streams. Keeping grass on the landscape helps reduce erosion, provides habitat for wildlife and can help keep pollution out of waterways.

“Tax policy should not have an impact on land-management decisions, especially those decisions that deal with conservation of our natural resources,” she said. “We don’t want short-term tax policy to affect long-term decisions.”

Possible paths forward

As early as 2016, legislators wanted to know if there was a more equitable way to determine the taxable value of farm and ranch land. That year, the Legislature funded an SDSU study on the topic.

Economists at SDSU analyzed two different methods for assessing taxable value of farm and ranch land. One method was based on the actual use of land and the other used a computer program to predict a piece of land’s most probable use. The idea was to account for individual management decisions and avoid forcing landowners to plow up grasslands just to pay lower taxes. The study also attempted to update the soil tables used for the current property tax assessment system. The SDSU researchers turned their findings over to the DOR.

In 2019, the Legislature ordered the DOR to do its own analysis of the SDSU study and take a look at what the impact on county and school budgets could be if either of the two models would be implemented. The DOR also took the chance to look at what would happen if the state soil tables were updated.

Semmler and DOR property tax expert Russ Hanson presented the DOR’s findings during the Oct. 24 Ag Land Assessment Task Force meeting. In addition to showing that both changes would likely result in millions of dollars worth of lost property tax revenue for counties and school districts, the DOR analysis found that seven counties haven’t adopted the Geographic Information Systems technology. GIS mapping would be essential tools for making assessments under either the actual use system or the most probable use system.

Adopting completely new tax assessment systems isn’t likely to happen any time soon, Cammack said. More likely are some tweaks to the options county equalizers have to make adjustments to property valuations and creating a process to allow landowners to have property taxes reduced on a limited number of parcels that have been non-production grasslands for decades.

“That would provide some incentives to keep that land in prairie grass,” Cammack said.

Those ideas will get more discussion during the Ag Land Assessment Task Force’s next meeting, which is set for Nov. 15 in Pierre, Cammack said..

Still, the DOR would like to begin implementing more modern soil tables, said DOR Property Tax Division Director Lesley Coyle. Until the 2019 Legislature required DOR to perform its analysis, no one had taken an accurate look at what updating the soil tables could mean for the state.

Simply updating the soil tables to reflect the more accurate, modern data found in the federal Natural Resources Conservation Service Web Soil Survey resulted in an increase of about $170,000 in county and school district tax revenues across the 11 counties DOR analyzed. The new tables would better reflect effects of recent flooding in the northeast and of salty soils and better farming practices, which would help to better distribute the property tax burden, Hanson said

“There are some areas that are helped tremendously,” he said.

Adopting new soil tables would only consist of an update of the state’s current property tax assessment system, so it could be done without legislation, Cammack said. Still, the DOR was considering a phased roll out to give counties without GIS mapping time to modernize, Coyle said.