Editor's note: This is the first of three articles that make up Part 2 of a two-week special report in which South Dakota News Watch is examining the failure of the state’s public school system to adequately educate Native American students. Last week, News Watch examined the problem and its causes; this week’s material focuses on new and ongoing reform efforts and hopes for invigorating Native education in South Dakota.

New efforts to better align school curricula and classroom teaching with the unique needs of Native American students are among the reasons for new hope that South Dakota may be turning a corner toward improving educational achievement for the state’s largest minority group.

Reforms are badly needed due to the state’s long-term failure to provide its Native American children with an education that leads to academic achievement. Test scores and graduation rates for South Dakota’s indigenous population — which makes up about 10% of students in the state — has lagged far behind other groups for generations. Lower educational attainment has been linked to dire later-in-life consequences such as generational poverty, high unemployment and higher rates of substance abuse and incarceration.

State Sen. Troy Heinert, D-Mission, is a former elementary school teacher who now serves as the Minority Leader in the Senate. Heinert, a member of the Rosebud Sioux Tribe, said some progress has been made in improving Native education in South Dakota and he believes the stage is set for more significant reform.

But Heinert said it will require more focus on understanding the unique ways that Native children learn and implementation of teaching methods specifically aimed at better reaching and connecting with Native students. Bolstering student self-esteem and strengthening identity through language and cultural education are key to academic success, he said.

”For years, it’s been, ‘Well, we’re going to roll a cart in here for 30 minutes a week and that’s when we’ll do language and cultural education,’ but the rest of the time we’re doing to do what we’ve always done,” Heinert said. “And that is not conducive to change.”

Beyond curricula changes, other initiatives are planned or underway to improve Native education in South Dakota, including efforts to hire more indigenous teachers, to heighten parental and community involvement in education, to expand higher-education and employment opportunities and to possibly create Native-focused charter schools.

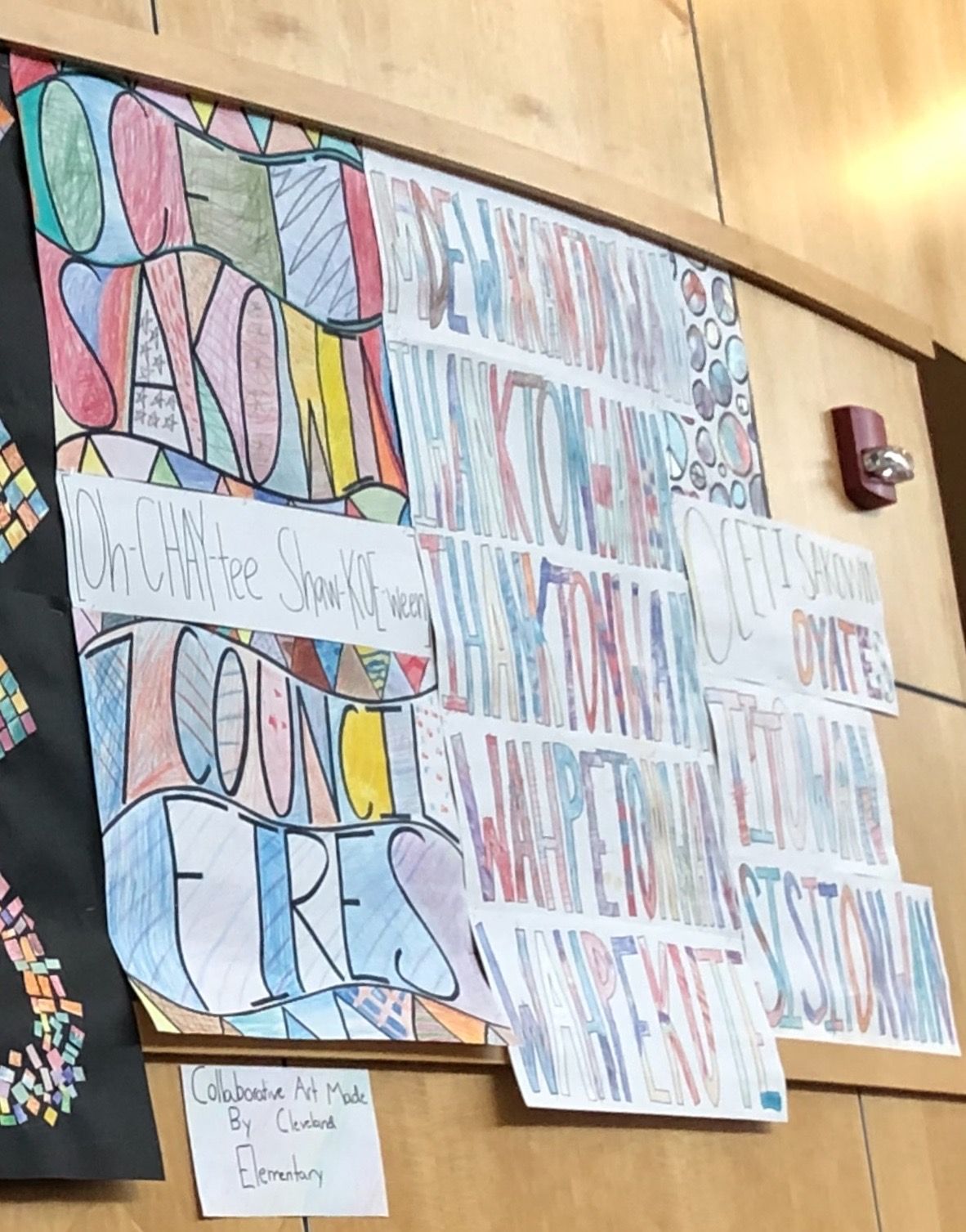

State education officials began the process of incorporating Native American language and culture into everyday lessons when the state Board of Education Standards officially made the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings part of the state’s social studies standards in 2015. The OSEUs are a set of education standards that incorporate Lakota language and culture and which were designed by tribal elders and educators.

Schools across the state have begun implementing pieces of the OSEUs into their curricula but have been slowed down by a lack of ready-made materials to aid in lesson planning, said Juliana White Bull-Taken Alive, director of the state Office of Indian Education.

“I see this as a problem, but I also see it as an opportunity for schools and organizations to create them,” White Bull-Taken Alive said.

Heinert also said Native-dominated schools and those on reservations should be granted “educational sovereignty,” which would allow for far more flexibility in recruitment and hiring of Native teachers and also give schools the ability to adjust curricula or teaching methods to find things that work for Native children.

“Our kids have a different style of learning, and I think once we can get that educational sovereignty, that’s when we’ll start to see some real gains and changing of the trends that have been around for 60-plus years,” he said.

In recent years, Heinert has served on two special legislative panels focused on education. The first effort provided nearly $2 million in grants called Native American Achievement School grants to three Native-dominated schools to improve teaching and learning. Two of the schools that received grants, Todd County Middle School and He Dog Elementary in Todd County, used those grants to improve their curriculums and develop a teacher training program for paraprofessionals.

The program devised by schools in Todd County will be the basis for more projects in Native American-dominated school districts as part of a partnership between the South Dakota Department of Education and McRel International, a non-profit education consulting firm working on behalf of the U.S. Department of Education, said Ben Jones, South Dakota education secretary.

Heinert also served on the Blue Ribbon Task Force that in 2015 proposed a half-percent sales tax increase that now generates millions of dollars each year to raise teacher pay. Officials say higher teacher salaries may be bringing more Native American college graduates back to the state to teach.

Recruiting more Native American teachers to work in schools serving tribal communities has been a point of focus for the national non-profit Teach for America and its South Dakota office. Some of the state’s highest-need schools are in Native American communities, and those communities were asking for more Native teachers, said Teach for America South Dakota Executive Director Jim Curran.

“For so long there were just so few Native American teachers,” Curran said.

The organization announced recently that its 2019 corps of teachers was its most diverse; nearly half of the new teachers were Native American, Curran said.

Heinert said he is trying to change the vernacular around Native education in South Dakota, adding that the focus on consistently low standardized test scores creates a false narrative that Native students are unable or unwilling to learn.

Native students should not be measured solely by test scores or graduation rates, but whether they are finding success as well-rounded people who can marry an understanding of their history and culture with the ability to function well in the modern world, Heinert said.

“One of the problems we have in Native schools or in predominantly Native schools is that the definition of success is coming from a non-Native perspective, and we have our own definition of success, of what does a good student look like,” Heinert said.

Expanding Native perspectives in schools

The lack of Native American representation in educational materials drove South Dakota education officials to begin work in 2018 on what became the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings. The idea was to create a comprehensive set of educational materials and standards based on Lakota, Dakota and Nakota perspectives on history, land use and language that could be used in all state classrooms. The term Oceti Sakowin translates to “seven council fires” and is the Lakota phrase used to describe the Sioux Nation.

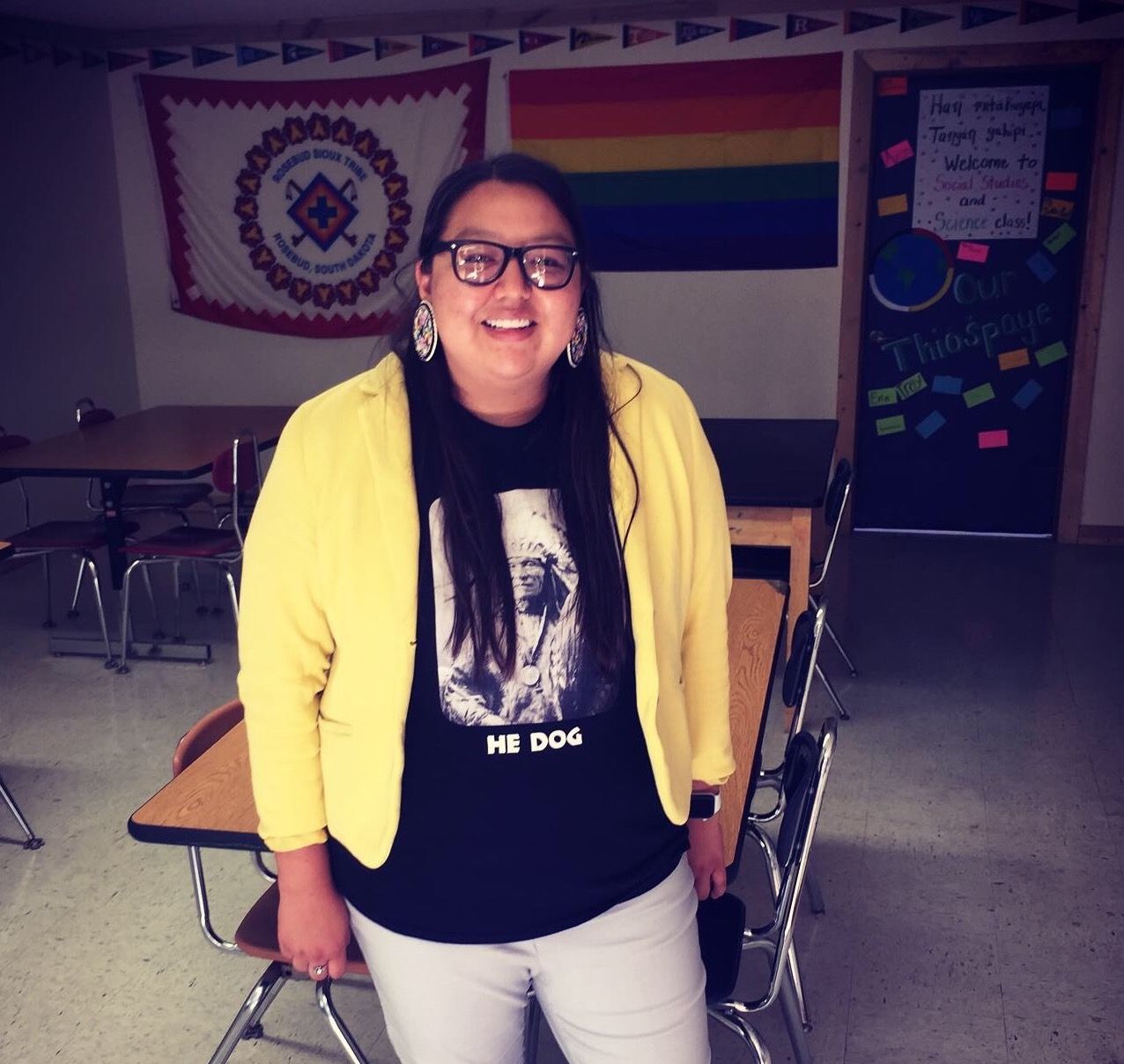

“For me, it’s a really helpful guide,” said Lydia Yellow Hawk, a new teacher at the He Dog Community School outside Parmelee on the Rosebud Indian Reservation in south-central South Dakota.

Yellow Hawk, a social studies and science teacher for 36 students in grades six through eight, has been finding ways to incorporate Lakota cultural lessons rooted in the OSEU in her lessons.

State science standards require middle-schoolers to be able to give a basic description of how gravity affects the movements of planets and galaxies through space. As it happens, many Lakota stories and beliefs involve the moon and stars. So, with a little help from Sinte Gleska University in nearby Mission, S.D., Yellow Hawk said she was able to incorporate some traditional Lakota understandings into her science lesson.

“We really do focus and put an emphasis on incorporating Lakota or indigenous worldviews and values,” Yellow Hawk said. “I’m teaching science and astronomy and learning about the solar system and the stars, alongside that … I’m teaching Lakota ideas of how those came to be and our worldview to my students.”

Incorporating Lakota culture into everyday lessons is a fairly new concept, even in public schools serving tribal communities. When Yellow Hawk was attending high school in 2014, Lakota language, philosophy and history all were taught as their own classes and students were only required to take one Lakota class to graduate, she said.

From the beginning, the OSEUs were intended to be incorporated into lessons in all state schools. But while the state Board of Education Standards has adopted the OSEUs, schools are largely on their own when it comes to designing the curricula that teachers use to actually teach to the standards. As a result, schools are adding the OSEUs to their teaching practices at varying rates.

At He Dog Community School, Yellow Hawk and her colleagues are building their own lesson plans. It isn’t easy, but they get help from Sinte Gleska University, Yellow Hawk said.

“So, not only am I writing lesson plans just for the kind of the school-required curriculum, but I’m also writing lesson plans for our own indigenous curriculum,” Yellow Hawk said.

A growing body of lesson plans and educational materials connected to the OSEUs are available online through the WoLakota project at wolakotaproject.org. The website has videos of interviews with tribal elders and groups of lesson plans designed by teachers in the Todd County and Rapid City school districts. Links to more resources are also expanding.

Yellow Hawk has a distinct advantage over most of her colleagues because she was born and raised near the He Dog school. She has drawn on friends and family for help, sometimes even asking her grandmother to visit school and help explain a topic.

The fact that she grew up in the same community as her students is one of the reasons Yellow Hawk became a teacher in the first place.

“It can be difficult, but it’s kind of helpful when, if I don’t know something, I can always feel like I have support if I run into challenges,” Yellow Hawk said.

Enter Jim Curran, executive director of Teach for America in South Dakota. Yellow Hawk had a few TFA teachers in high school, so she was familiar with the organization when Curran first made contact. She met with a few TFA recruiters in Ohio and in 2017 was invited to the organization’s Native Alliance Initiative summit.

Teach for America is a national organization that recruits and trains teachers to work in disadvantaged communities for two years. In South Dakota, the organization focuses much of its efforts in tribal communities. One of the organization’s biggest shortcomings when it began operating in South Dakota, Curran said, was its lack of attention to recruiting Native American teachers. From 2004 — when the TFA began operations in the state — to 2011, only five Native Americans were hired as teachers.

“Kids and families in the communities where we work have been demanding an education that is more responsive and reflective of who they are,” Curran said.

The organization responded to that demand by creating the Native Alliance Initiative, which is focused on recruiting Native American college graduates to become teachers. From 2011 to 2019, TFA has brought in 33 teachers who are Native American. In early November 2019, the organization announced that 42% of its 2019 of new teachers were Native American. Next year, Curran said, TFA wants its teacher corps to be 50% Native American.

“We’ve just gotten less willing to accept the line that, ‘Oh there’s just not enough Native American college graduates,’” Curran said.

Hiring teachers who look like their students and have similar backgrounds has tremendous value, Curran said. For one thing, students see that people like them can be leaders and can accomplish great things, he said.

“There’s power in that,” Curran said.

Teachers from low-income or Native backgrounds also bring a different approach to the job, Curran said. In Yellow Hawk’s case, that means making sure her students, even as early as middle school, know that they can go to college.

“At the middle-school level, a lot of (students) don’t really know what their goals are for after high school, so I like being able to work with them to help them get through those ideas and think about education,” Yellow Hawk said.

Teach for America isn’t the only organization in the state putting more effort into recruiting Native American teachers. The Sioux Falls School District has set up what it calls a teacher pipeline aimed at encouraging some of its students to become teachers, said Dr. James Nold, an assistant superintendent. The district has been trying to identify and recruit Native American students into its Teacher Pathway Program, created two years ago as part of a larger effort to improve outcomes for its indigenous students.

“We have a handful of students right now that I’m very excited to have back in four years when they complete their college degree,” Nold said. “They can be teachers for this school district so that other students can see success and say, ‘That’s an avenue that I could also achieve.’”

Connecting Native students to the classroom

One of the biggest challenges facing Native American students is maintaining regular attendance, Nold said. State data show that indigenous students have the lowest attendance rate at 72% and the highest rate of chronic absenteeism at 37%. In the Sioux Falls district, the Native American student attendance rate is 65% and the chronic absenteeism rate is 51%. For all students in the district, attendance is at 91% and chronic absenteeism is 18%.

Relationships between students and their school, specifically any adults in the school, are one of the biggest factors in whether a student attends regularly, Nold said.

“We know that as we meet with our attendance committees, when students start to build relationships, when they start to bond, to build some type of relationship, their chances of attendance improving or being strong increase,” Nold said. “That definitely benefits the child and the [academic] success rate increases dramatically as attendance increases.”

As part of its efforts to encourage Native students to build relationships at school, the Sioux district started integrating the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings into classrooms as early as 2012. The district has also created high school Lakota language courses that count toward graduation requirements. Lakota Connections classes are offered at two of the district’s three high schools and at middle schools with high concentrations of Native students, Nold said.

The connections class has become an important piece of district efforts to improve Native American student outcomes, Nold said. The teachers in those classes spend part of their time acting as case managers for their students by providing individual support for such things as connecting to local cultural organizations. The district has also worked on creating clubs that celebrate Lakota culture, Nold said. Club members take trips to sacred sites and compete in the Lakota Language bowl at the annual Lakota Nation Invitational basketball tournament in Rapid City.

Sioux Falls district begins efforts to boost attendance rates as early as elementary school, with counselors called liaisons that work individually with families to ensure they have everything needed to get their children to school.

“They’ll target attendance as a predominant factor of what they go out and do. But they really, really try to work to build that relationship so that families feel very comfortable coming and asking when they have problems or needs,” Nold said.

Another improvement in Sioux Falls was the creation of a Native American parent advisory committee, which meets regularly to give the district feedback and suggest ideas. Increasing parental involvement in education is seen as a critical element of improving student engagement and academic success.

Sioux Falls is not alone in its efforts. The Wagner School District on the Yankton Sioux Reservation in south-central South Dakota brought the Jobs for America’s Graduates Program to the state in 2009.

In Wagner, the program seeks to help middle- and high-school students — Native and non-Native — who live in poverty or face other issues likely to reduce attendance and increase the chance of dropping out. Each class consists of about 12 students chosen by a committee. The idea is to create an extra layer of support for those students, said Neil Goter, Wagner High School principal.

Students in the program get individualized help and support from JAG teachers and develop close relationships with fellow students, who often share similar life experiences. In middle school, JAG classes work mainly on improving social skills and providing experiential learning such as working as a member of a team, Goter said.

“Some kids are going to come to JAG class and not have all those skills, and that’s why these kids have some barriers and they need some assistance with some of those areas,” Goter said.

In high school, the JAG program changes focus toward academics and preparing students for life after high school. Students can get help with homework and filling out federal financial aid forms for college and are exposed to careers. The goal is to achieve a 90% graduation or degree equivalency rate and an 80% job, college or military placement rate.

The program has proven successful, Goter said. Graduates from Wagner’s JAG program have gone on to college or tech school, joined the military or gone straight into a job, Goter said. One student who found success was Alexander “Zane” Zaphier who graduated high school in 2013 and went on to serve in student government at the University of South Dakota. Zephier graduated with his bachelor’s degree in 2017 and now works for USD’s Upward Bound program, which offers counseling and help for high school students whose parents didn’t go to college.

“He’s really paying it forward,” Goter said of Zephier.

Another solution to the attendance issue is creating a deep relationship between the school building itself within the community it serves. In the Oglala Lakota County School District, for example, administrators have tried to keep their schools as open as possible to students and the public, said Dr. Anthony Fairbanks, district superintendent. The schools on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in southwester South Dakota hold events such as basketball tournaments and provide free meals when possible, he said.

The idea is to make the schools a big a part of the community. “The more you open your doors, the more you connect to the community,” Fairbanks said.

The philosophy appears to be working. The district, whose population is almost entirely Native American, had a 97% attendance rate last year, according to the state school report card. Fairbanks said the district plans to create an even deeper connection between the people of Pine Ridge and the Oglala Lakota County School District through the biggest educational project in decades — a new high school.

New school, new focus in under-served area

Lakota Tech High School, the first career and technical high school on a South Dakota Indian reservation, is planned to open before the 2020-21 school year on a site near the Wolf Creek Elementary School a few miles outside of Pine Ridge. The school is central to an ambitious $25 million project aimed at providing sorely needed job training within the Pine Ridge community, while at the same time aligning the school’s core curriculum to the history and culture of the Oglala Lakota people, Fairbanks said.

“That means involving not just the teachers, but also the elders and community members and teachers who’ve been here for a really long time. We have a lot of great knowledge here within the community and we need to be finding ways to access that and leverage that to make sure that our students are really gaining a holistic education,” said Stephanie Eisenmenger, principal of the future high school.

Pine Ridge hasn’t had a public high school in decades. High school students must transfer to a new district, attend a virtual high school online or go to one of the private or Bureau of Indian Education schools on the reservation. That situation is far from ideal, Fairbanks said. With help from state government in securing low-interest loans, the district was able to bring the high school to fruition.

The plan is to create several academies within the school that will specialize in areas the Pine Ridge community has said are needed, Eisenmenger said. All students will start in the freshman academy, which will be designed to ease students’ transition into high school, develop study skills, and provide a chance to experience a few different career paths. The school will also include a business and entrepreneurship academy, a health and public service academy as well as a Science, Technology, Engineering and Math Academy. An agriculture academy is possible too, Eisenmenger said.

“Our goal for all of these pathways is that students will graduate not only with a diploma but with some form of industry based certification so that they can actually jump right into the workforce or they get a leg up going into either a four-year college or vocational school,” Eisenmenger said. “Whatever pathway they want to go down for their life, they will be able to have a competitive advantage when they graduate.”

As of October 2019 there were 115 teaching and staff positions yet to fill at Lakota Tech High School, Fairbanks said. But the school has a few things working in its favor, when it comes to hiring a new staff.

“One advantage that we have is that we’re doing something really different and we’re doing something that means a lot to this community. And I think that a lot of people go into teaching to make a difference and to have an impact,” Eisenmenger said. “Working at Lakota Tech, we can really change people’s lives, and we can boost this economy and do something really great for not just the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, but for South Dakota in general.”

A separate group, led by members of the non-profit NDN Collective is working on legislation that would allow for the creation of a series of charter schools focused on Native American education.

Heinert, the state senator, said he supports an effort to propose legislation in 2020 and said he may sponsor the legislation. If the legislation were to become law any schools created would be first charter schools in South Dakota. They would be funded with state and local tax dollars but operate independently and therefore have greater flexibility to innovate and adapt quickly.

Whether that legislation moves forward or not, Heinert said he will continue to push his legislative colleagues and the Department of Education to gain a greater understanding of the challenges and opportunities that exist in how Native children are taught in South Dakota, and to push Native leaders and families to also become more involved in the process.

“I’m extremely hopeful,” he said. “We’ve started to become part of the system of change, of how do you change a school or a state and how do we go through that process. If we can teach in a culturally relevant manner, our scores will come up. But we can’t go into this just trying to improve scores; we need to go into this to help these kids know who they are and where they came from and to teach them accordingly.”

— South Dakota News Watch reporter Bart Pfankuch contributed to this report.