An earlier-than-normal and more virulent strain of RSV infections in South Dakota is causing severe illness in young children, sparking concerns that pediatric intensive care units could become strained, especially if combined with a winter spike in influenza or COVID-19 cases.

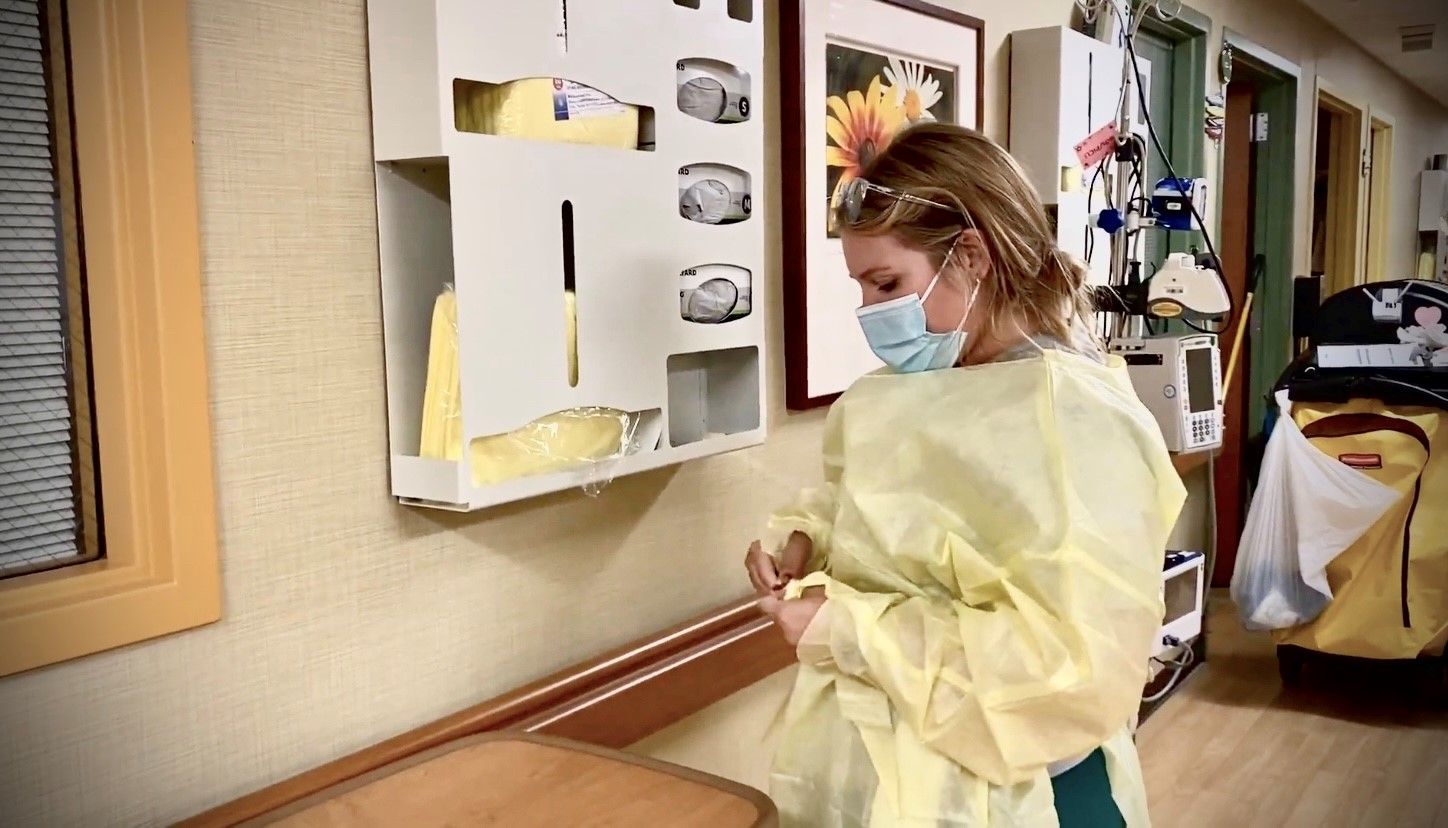

RSV (respiratory syncytial virus) is a common, highly contagious infection for children under 2 years old that typically surges in January and February. Representatives of Avera and Sanford health systems say they started seeing increased RSV clinic visits and hospital admissions in late October and early November, with the most ill patients put on ventilators to assist breathing.

Nationally, nearly 20% of tests for RSV were positive for the week ending Oct. 29, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, almost twice as high as in early October. South Dakota’s test positivity for the week ending Oct. 29 was listed as 12%, up from 5% at the start of October, the CDC said. That reported rate, however, “seems low” compared to what doctors are seeing in the state, according to Kara Bruning, head of pediatrics at Avera McKennan in Sioux Falls.

“I can tell you clinically that it feels much higher than that,” said Bruning. “Almost everyone that I’ve seen in the pediatric hospital right now has RSV. It’s hitting hard this year. If influenza or COVID comes and becomes a higher percentage of admissions, we’re going to have trouble in pediatrics.”

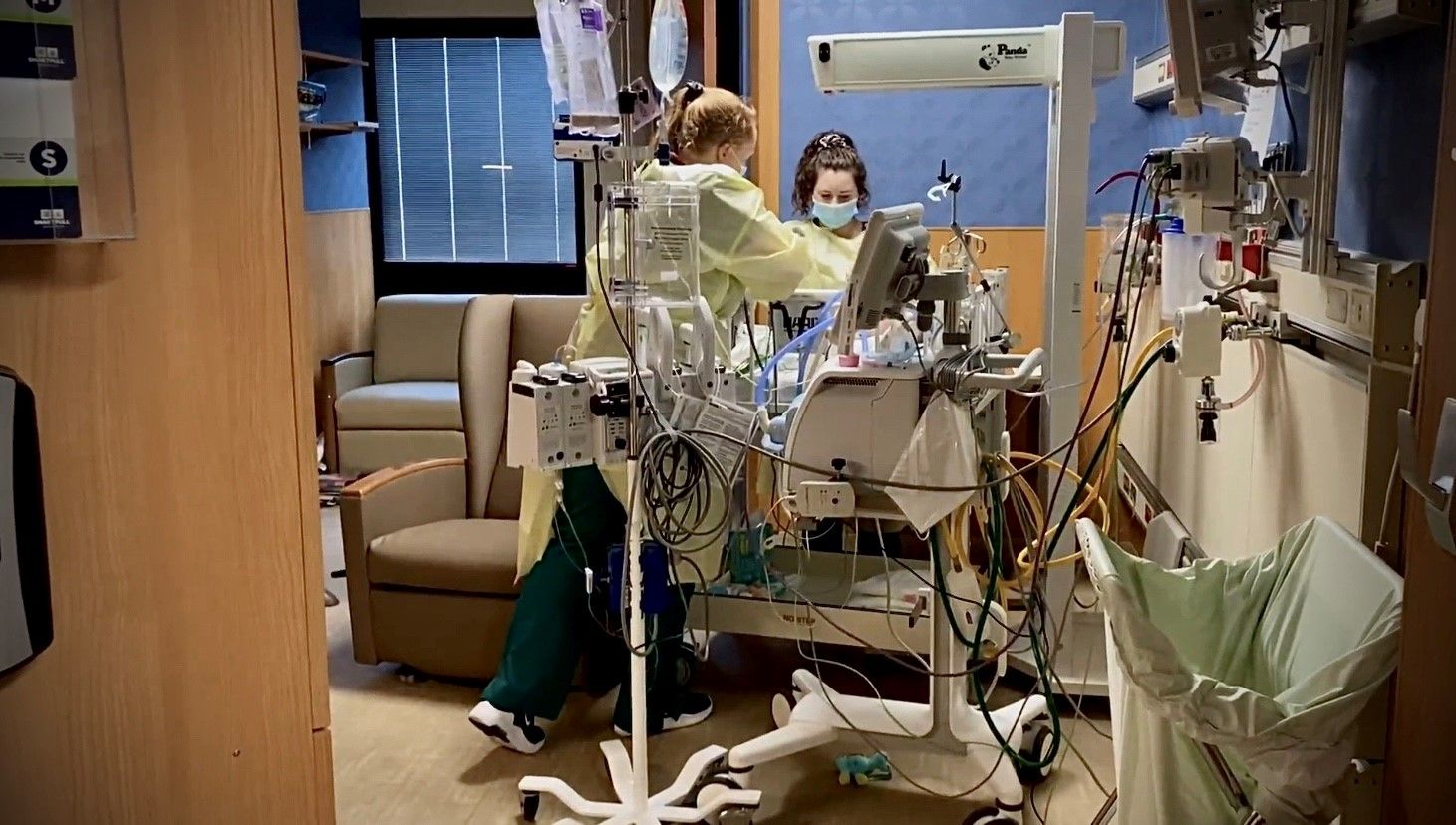

Bruning said Avera’s pediatric intensive care unit has been at or near capacity for several weeks and that staff is preparing to remain at those levels “for the near future.” The pediatric ICU at Sanford is about 75% full, according to Sanford Children’s Hospital vice president and medical officer Joe Segeleon, with the possibility of handling patient overflow in separate units if needed.

“In talking to our pediatric [specialists], they seem to think the virus is more virulent this year,” said Segeleon. “Pediatric hospitals every year experience a surge in RSV, but to their observations the kids are pretty sick this year.”

RSV is spread through droplets released into the air when an infected person coughs or sneezes, or by touching a contaminated surface; RSV can also be spread through direct contact with an infected person, according to the CDC.

An estimated 60,000-80,000 children under 5 years old are hospitalized nationally each year due to RSV infection, typically due to inflammation of the airways from mucus buildup or pneumonia-related infection of the lungs. Adults 65 and older and those with chronic heart or lung disease or weakened immune systems are also at risk of severe RSV infection.

The CDC recently issued an alert that “surveillance has shown an increase in RSV detections and RSV-associated emergency department visits and hospitalizations in multiple U.S. regions, with some regions nearing seasonal peak levels.”

There is currently no vaccine for RSV, but the U.S. Food and Drug Administration on Nov. 2 granted fast track designation to an intranasal RSV vaccine candidate developed by Codagenix, with a Phase 1 dose escalation study scheduled for early 2023.

The South Dakota Department of Health and state Epidemiologist Josh Clayton did not respond to multiple requests for information from News Watch regarding the state’s response to rising RSV cases. Medical experts on the ground, meanwhile, are reacting with measured caution as they keep a close eye on the number of hospital admissions and ICU visits.

“Most cases of RSV are going to have a cough and runny nose and be fine,” said Bruning. “A small percentage are going to be wheezing and require help such as nebulizers, and an even smaller percentage of them are going to be hospitalized. That being said, we are seeing very sick kids this year that are needing to be hospitalized and it’s happening at an odd time and we’re seeing high numbers of them. So that’s where we are.”

‘He was really struggling’

Kim Stone noticed her 1-year-old son, Junior, coughing more than normal on the weekend of Oct. 8-9, but she wasn’t overly concerned. When she woke him up for a nap that Monday, however, he seemed extra wheezy. Stone took him into a local clinic along with her 4-year-old daughter, Haven. Both children tested positive for RSV.

While Haven never developed more than a bad cough, Junior’s symptoms grew worse. He was given steroids Oct. 11 when his breathing became more rapid, and by the next morning he was visibly short-winded, with a lot of retraction in his neck and rib cage.

“He was really struggling at that point,” said Stone, 27, who lives in Madison and works at Little Explorers Childcare in Sioux Falls. She took him to the emergency room in Madison, where he was given an IV for dehydration and put on full oxygen because his levels were low.

“Thirty minutes after he was admitted to the Madison hospital, he had to be airlifted to Sanford Children’s Hospital in Sioux Falls,” Stone said. “He wasn’t improving at all.”

She made the drive with her husband, Josh, hearing the words “respiratory distress” and “viral pneumonia” in her head. “It was really scary,” she said of the diagnoses she had heard from doctors, “but we knew he was in good hands.”

Junior received full oxygen through a ventilator in Sioux Falls, plus an IV because he wouldn’t eat or drink. By the third day, doctors had weaned him off the oxygen a bit, and he started playing with his toys on the floor and seeming more like himself. By the end of that day, he was released from the children’s hospital and returned to Madison with his family.

Stone estimates that as many as five children (including Junior) from the Little Explorers Childcare facility where she works have been hospitalized this fall from RSV. Numerous others have tested positive and been kept home, a trend not uncommon during a community surge.

“Respiratory illnesses have a tendency to go through daycares,” said Segeleon. “In children that are very young, less than four weeks of age, it may present as apnea, where they quit breathing. In kids a year old or younger, they can have a lower airway condition called bronchiolitis, which is inflammation and mucus plugging buildup in the very small airways. In older kids, it’s frequently a cold, but if they have underlying conditions, it can be more serious.”

The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends that children be excluded from daycare or school if they have a temperature above 101 degrees or display signs and symptoms of illness such as sore throat, rash, vomiting or diarrhea. The association and CDC also stress good hand hygiene and urge parents to keep children up to date on recommended immunizations.

Stone said the staff at Little Explorers disinfects surfaces and toys throughout the day and tries to keep the children “out of each other’s faces as much as possible.” Any child with a temperature above 101 degrees is sent home for at least 24 hours.

Junior is happy to be home, she said, but he needs to take two puffs of an inhaler twice a day to help with breathing, a routine that the 1-year-old hasn’t responded to favorably.

“He doesn’t like it much,” Stone said. “But we’re glad to have him back.”

Immunity impacted by pandemic

Last year, South Dakota experienced a summer spike in RSV, with cases peaking in July. Segeleon said most experts attributed that rarity to a disruption in the “cadence of infectious disease and viral exposures” due to societal changes made during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic.

“We went through a period where pediatric visits were dramatically decreased,” said Segeleon, who specializes in pediatric critical care. “They decreased because schools were closed [in the spring of 2020] and we decreased the amount of socialization, including after-school activities and social programs.”

Other COVID-19 precautions were also a factor in keeping overall infections low, he said.

“We were also significantly more cognizant of things like hand hygiene and to some degree mask wearing. All those things reduced the infectious load and exposures in children and adults for a given period of time, and I don’t know how long it will be until our cadence is back to normal.”

While RSV test positivity rates were higher during the 2021 summer spike than this fall, Avera’s Bruning said the surge “hit fast and was fairly mild and then it was gone.” Health experts are exploring the possibility that pandemic-related disruptions may have impacted immune properties, making some children more susceptible to respiratory viruses and increasing the severity in some cases.

“We’ve had this whole cohort of young children who haven’t had that usual constant exposure to viruses at day care or in preschool or out in the community,” Vandana Madhavan, director of advanced pediatrics at Mass General Brigham in Boston, told NPR. “And so now they’re getting exposed and it’s hitting them really hard.”

As for the current RSV wave, Bruning said it will depend how long it lasts and whether it remains highly virulent before health systems can assess the possibility of concurrent surges of RSV, flu and possibly COVID-19 and what that might mean for pediatric resources.

“I pray that it doesn’t happen,” she said.

RSV: What you need to know

Here is a brief overview of what parents and others should know about RSV, a virus infecting thousands of children across South Dakota and the U.S.

SYMPTOMS

People infected with RSV usually show symptoms within 4 to 6 days after getting infected. Symptoms of RSV infection usually include

- Runny nose

- Decrease in appetite

- Coughing

- Sneezing

- Fever

- Wheezing

These symptoms usually appear in stages and not all at once. In very young infants with RSV, the only symptoms may be irritability, decreased activity, and breathing difficulties.

PROVIDING CARE

- Manage fever and pain with over-the-counter fever reducers and pain relievers, such as acetaminophen or ibuprofen. (Never give aspirin to children.)

- Drink enough fluids. It is important for people with RSV infection to drink enough fluids to prevent dehydration (loss of body fluids).

- Talk to your healthcare provider before giving your child nonprescription cold medicines. Some medicines contain ingredients that are not good for children.

EXTREME CASES

Healthy adults and infants infected with RSV do not usually need to be hospitalized. But some people with RSV infection, especially older adults and infants younger than 6 months of age, may need to be hospitalized if they are having trouble breathing or are dehydrated. In the most severe cases, a person may require additional oxygen, or IV fluids (if they can’t eat or drink enough), or intubation (have a breathing tube inserted through the mouth and down to the airway) with mechanical ventilation (a machine to help a person breathe). In most of these cases, hospitalization only lasts a few days.

Source: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention