A widespread shortage of primary care physicians in rural South Dakota is putting many of the state’s residents in danger of not being able to access the regular, preventive healthcare they need to live healthier lives. The shortage is being driven, in part, by a lack of post-graduate training opportunities — known as residency — focused on training doctors to work in rural communities.

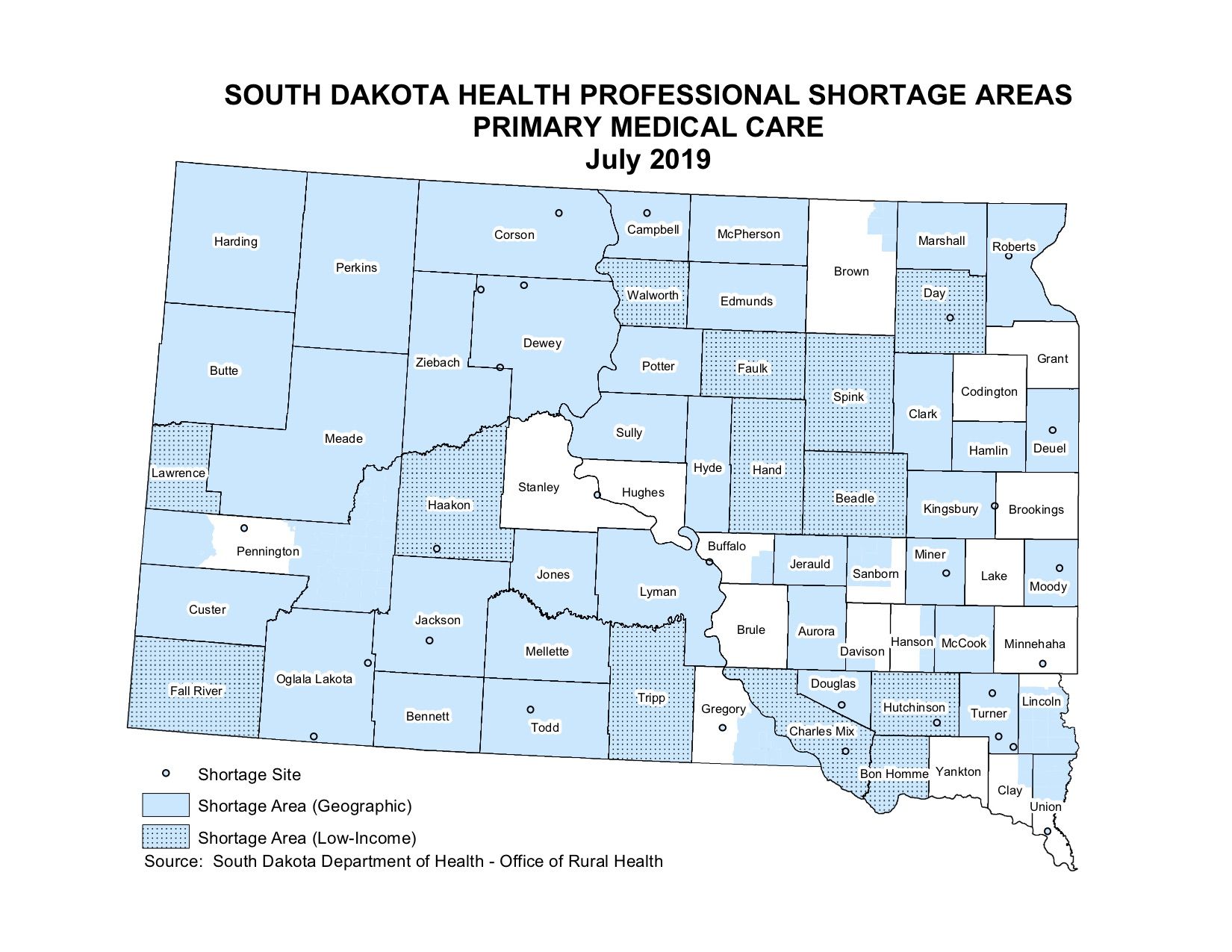

The doctor shortage is widespread in rural South Dakota. A map created by the South Dakota Department of Health shows that ready access to primary care physicians is available only to residents along the Interstate 29 corridor, a few areas in the central Missouri River region and around the Black Hills in the west. Most other areas of the state are considered to be in a shortage of access to primary medical care.

According to the department, nearly all of the state’s counties are also home to communities that are medically underserved in terms of access to proper health care.

While physician shortages are expected all over the country thanks to an aging population with increasing longevity, rural areas of the country are expected to be among the hardest hit

“Rural areas have been particularly at risk for losing doctors and losing hospitals,” said Dr. Robert Summerer, a surgeon and president of the South Dakota State Medical Association. “That puts women who are delivering babies and the elderly in danger because it takes a long time to get to the care they need.”

The American Association of Medical Colleges, in an April 2019 report, predicted the country would be short between 21,100 and 55,200 primary care physicians by 2032. The same report, called “Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand,” predicted smaller shortages in medical specialties such as psychiatry, general surgery and neurology as well. Overall, the AAMC report predicts a physician shortage of between 46,900 and 121,000 doctors by 2032.

A large and growing part of the problem is that there aren’t enough post-graduate training positions in places that most need primary care physicians, general surgeons and obstetricians, Summerer said.

Even after finishing a minimum of eight years of school between college and medical school, modern doctors can’t actually practice medicine without first training in a specialty as what is known as a medical resident. Basically, doctors must apprentice themselves to more experienced doctors in order to learn their craft.

Such training lasts between three and seven years, depending on the demands of the specialty. A neurosurgeon, for example, will spend seven years working up to 80 hours per week performing countless surgeries under the supervision of more experienced surgeons before he or she can perform alone. The idea is to cram as much experience into a physician’s mind and body as possible so that when they see patients on their own, they can better handle the routine and the unexpected.

Still, practicing medicine hundreds of miles from the nearest specialist, much less a more experienced physician, can be nerve-racking for new doctors, Summerer said. The isolation is one reason newly credentialed medical doctors are so much more likely to work within an hour’s drive of where they completed residency, the final step in their training. As many as 70 percent of doctors will go into practice within 80 miles of where their residency was located, studies have shown.

Nationally, residency programs are clustered in busy, major metropolitan areas. New doctors need to get as much experience as they possibly can before practicing on their own, which means they need to see a lot of patients with a lot of different problems.

Training doctors tends to be expensive, involving classroom work, mentoring and even paying a resident’s salary. As technology has advanced, training programs have become more expensive, which tends to force training programs to concentrate in larger, better-funded hospital systems. One study by researchers at the University of Washington School of Medicine found that a family practice resident’s training — one of the shortest resident training periods — cost hospitals about $180,000 once federal reimbursements, state and other funding sources were accounted for.

The problem has been compounded by how residency programs are paid for. In the 1960s, with the creation of Medicare, taxpayers began picking up a large portion of the cost of residency programs because educational activities were found to increase the quality of care at hospitals. More money meant more positions could be created and more doctors could be trained. Then, in 1997, thanks to the 1996 Balanced Budget Act, the amount of money the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services could spend on residency programs was capped. Since then, growth in the number of residency programs available to graduating medical students has slowed.

“We’re creating a bottleneck,” Summerer said.

Twenty years ago, the number of medical school graduates was smaller and the country’s physician workforce, much like the overall population, was younger. Today roughly two of every five doctors is projected to be over the age of 65 by 2032, according to the AAMC report “Complexities of Physician Supply and Demand.” Already about 15% of the country’s doctors are 65 or older, the report said. Another 27% are between the ages of 55 and 64, meaning 42% of the country’s doctors are nearing retirement, according to the report.

Over the last 10 years, South Dakota has become a microcosm of the national issue. Beginning in 2015, the state’s lone medical school, the Sanford School of Medicine at the University of South Dakota, began a process to grow the school’s student body by about 20 percent. The school increased the size of its freshman classes from 56 to 67 in each of the past four years.

The number of residency programs available to medical school graduates in South Dakota has increased, too, but not as quickly. According to data compiled by the National Residency Match Program, the nonprofit organization that assigns medical students to residency programs, the number of residency programs in South Dakota rose from about 33 in 2009 to roughly 52 in 2019. The growth was seen in the key specialties of family medicine, psychiatry, pediatrics and general surgery.

The creation of a new general surgery residency program based in Sioux Falls in 2014 added three first-year residency openings in the specialty which focuses on soft-tissue surgeries such as appendix removals. Six new pediatric residency positions were created at the Sanford Children’s Hospital in Sioux Falls. There were four new first-year psychiatry residency positions created at the Avera Behavioral Health Center in Sioux Falls. Another residency position was added in pathology and three internal medicine residency positions were created too. All of them are based in Sioux Falls.

Statistically, most of the fully trained physicians the Sioux Falls programs produce are going to end up working within an hour’s drive of the state’s largest city. According to the South Dakota State Medical Association, 80% of the doctors who train in the state wind up practicing in the state.

South Dakota’s newest residency program, which is aimed squarely at training and placing doctors in rural hospitals, can help address the problem.

The doctor most people spend the most time with, their primary care physician, typically spends three years specializing in family or internal medicine during their time as a resident. Primary care doctors are supposed to serve as the first line of defense against health problems. As such, family medicine residents spend their roughly 12,480 hours of training with a broad range of specialists in order to gain as wide a range of experience as possible to provide as broad a range of help to their patients as possible.

The Pierre Rural Family Medicine Residency program was conceived in 2015 as a partnership between Sanford Health and Avera Health, both as a way to ease the trouble both systems have in recruiting and retaining doctors in rural areas. The program is a way to provide new doctors with experience working in more remote locations, said Dr. Thomas Huber, family practice physician at the Sanford Health clinic in Pierre who was tapped to lead the program.

South Dakota then-Gov. Dennis Daugaard supported legislation that appropriated more than $200,000 from the state treasury in 2016 to help get the program started; both Avera Health and Sanford Health are helping fund the residency program.

Pierre is an ideal location for a rural residency program for several reasons, Huber said. The 2018 addition of a state-of-the-art cancer center to the local Avera St. Mary’s hospital has dovetailed with Avera Health’s efforts to improve the hospital’s specialty care. The joint efforts have provided medical residents with experience working with a fairly wide range of specialists. The hospital and the Sanford Clinic also draw patients from a more than 100-mile radius around Pierre, so there will be enough patient volume for the residents to get the experience they will need.

“I call it the black hole of South Dakota, North Dakota, and into Nebraska … for a lot of things, one of which is healthcare manpower,” Huber said.

The plan is to have six physicians-in-training in the program every year. Recruits for the Pierre-based program will spend their first year in Sioux Falls, seeing a high volume of patients and working with specialists that are not based in Pierre. Once the residents move to Pierre, they will spend two years seeing patients out of the capital city’s Sanford Health clinic while working on four-week rotations with the surgeons, oncologists and other specialists that are based in Pierre.

The Pierre program’s first two residents, Drs. Abby Serpan and Gene Campbell, started work in Sioux Falls in July 2018. They have now been working in Pierre since September.

Both physicians are examples of a less obvious advantage the Pierre rural residency program could provide for the state’s rural hospitals. Recruiting doctors to rural communities often is more about finding candidates who grew up in rural areas or had a love of rural living prior to medical school. Both Serpan and Campbell said they grew up in small towns, like to hunt and fish and always intended to work in rural areas. Finding a residency program tailored to their career goals was a tremendous opportunity.

Serpan hails from Dodge City in western Kansas and went to college at Fort Hays State University in Hays, Kansas. She attended medical school at a relatively new satellite campus of the University of Kansas School of Medicine in Salina that was created specifically for students who wanted to work in rural settings. Serpan said rural communities need quality health care and she wants to be part of providing it.

“What really shaped me was own health issues. My pediatrician, when I was younger, found I had congenital scoliosis. I had to have surgery at a young age. And Dodge City is as a rural community and if I hadn’t had a doctor there, who had caught it, they told me I would have been paralyzed by middle school,” Serpan said.

Campbell said he had considered becoming a doctor earlier in life, but he never thought it was a realistic option. Once he was married and had children, however, he decided to take the risk and go to medical school.

Eventually, Campbell found his way into medical school in Chicago. City life, he said, was not for him. When it came time to look for a residency program in 2017, the Pierre program stood out because it was in a relatively small community and because it was new.

“I was able to make history without really trying,” Campbell said.

Campbell said he’s already signed up with Sanford Health to work in Wahpeton, North Dakota, a town of about 7,800 people on the state’s border with Minnesota, once he finishes his residency training.

Huber said it will be several years before the Pierre residency program’s impact can really be evaluated. The deciding factor will be whether enough of the program’s graduates have gone into practice in rural settings, Huber said.

“Developing training programs that produce physicians that are comfortable living in rural areas, that have the skill set to take care of the people who live in areas, is what this program is all about,” Huber said. “I feel very strongly that this is needed.”