South Dakota health and medical officials are fighting an uphill battle to prevent the spread of potentially deadly infections that are increasingly resistant to antibiotics.

The state in recent years saw a pair of outbreaks of CRE, an intestinal bacteria that is almost completely resistant to antibiotics and that has a mortality rate that can rise to 50 percent. Both South Dakota outbreaks – one in the northeast corner of the state in 2012 and the other in the southeast in 2017 – took place in medical settings and were contained by a team of medical experts before significant spreading and without known fatalities.

Cases of CRE, or Carbapenem-resistant Enterobacteriaceae, which in some forms has been described by federal health officials as a “nightmare bacteria,” have risen steadily in South Dakota since official recording of cases began in 2012. The first year, 12 cases of CRE were reported. That number jumped to 37 cases in 2015, 58 in 2016, 64 in 2017 and saw a slight drop to 52 cases in 2018, according to the state Department of Health. Most cases can be treated by a cocktail of antibiotics but some CRE cases do not respond to treatment.

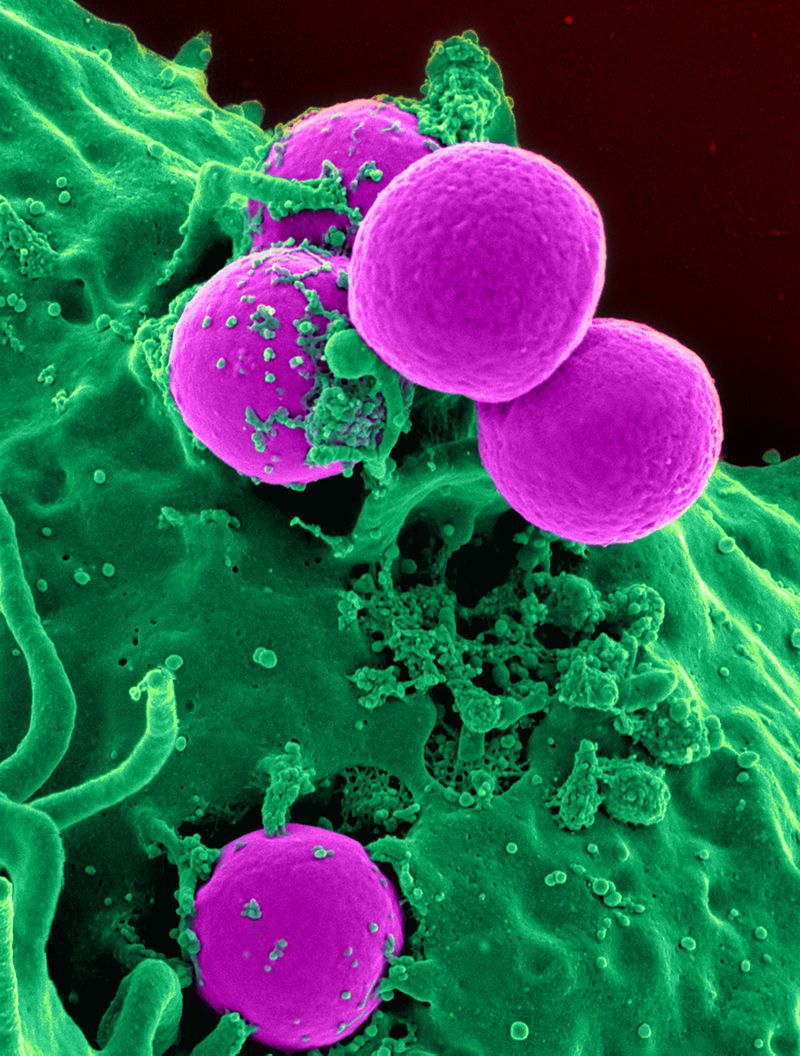

However, other illnesses caused by bacteria that show antibiotic resistance have a longer history in the state, including Methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus, better known as MRSA. Over the past decade, the state has seen 1,085 cases of MRSA, an infection that usually arises in hospital settings, is difficult to treat and can lead to death in rare cases.

The two CRE outbreaks and the rise of other bacteria that cannot be killed by antibiotics have put health-care workers in South Dakota on alert, with heightened efforts to stop the spread of antibiotic-resistant bacteria and to prevent more bacteria from becoming resistant.

The state’s major health providers and organizations have formed infectious-disease teams to study antibiotic resistance and educate medical practitioners and patients to improve safety, among other efforts.

Since 2016, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has spent $241 million to help state and local health combat antibiotic resistance; South Dakota received $432,000 from the CDC in fiscal 2018 for that purpose.

Across the U.S., antibiotic-resistant bacteria caused 2 million illnesses and led to 23,000 deaths in 2016, according to the CDC.

The rise in antibiotic-resistant bacteria is a global issue, driven by a history of improper dispensing of antibiotics by physicians and improper use by patients, as well as a slowing of efforts by pharmaceutical companies to develop new antibiotics that might be more effective but aren’t as lucrative as other drugs.

The fragility of systems aimed at preventing the spread of infectious diseases has been exposed in recent months by the outbreaks of measles in some states. Experts blame a lack of immunizations of some children as the impetus for the outbreak, which so far has not touched South Dakota.

State medical providers and health officials stop short of calling the rise of antibiotic-resistant bacteria a crisis, but concerns are growing that someday soon infections that were historically treatable with antibiotics may become untreatable.

“I think where we end up is that with increasing frequency, we’re going to see more and more resistant infections in more and more patients, and that is very, very concerning to us,” said Dr. Wendell Hoffman, a consultant with Sanford Health in Sioux Falls who is one of the state’s leading experts on infectious diseases. “I’m very worried about certain organisms, and we track them, and sometimes even 40 years after I graduated from medical school I will still break out in a cold sweat because there are certain things that are very, very dangerous and life-threatening and can take somebody out of this world in a short period of time.”

Global problem, local impacts

A great irony of the growing bacterial resistance to antibiotics is that each time antibiotics are effectively prescribed to cure an illness, the chance for future resistance rises.

In its extensive literature on the subject, the CDC shows how easily resistance can occur. Germs exist in the human body, some helpful and some harmful. Antibiotics are used to kill most of the harmful bacteria causing an illness, but they also kill some bacteria that protect the body from infection. With the good bacteria reduced in number, some drug-resistant bacteria are allowed to remain and flourish. Those antibiotic-resistant bacteria can then spread resistance to other bacteria in the body.

From there, the antibiotic-resistant bacteria can spread from person to person, eventually taking hold in some people and making them sick. The problem is compounded when antibiotics are prescribed when not needed, or if a patient doesn’t take all of the medication prescribed, again allowing the strongest of the antibiotic-resistant bacteria to proliferate. The picture worsens when antibiotics are used in animal feed, which allows resistance to grow in animals which are then consumed by humans.

Humans can be exposed to animal wastes or improperly handled meat, generating more resistance. People who get sick go to the hospital, where the chance of spreading is even greater because multiple bacteria are often present in great quantities.

The battle to prevent resistance has been waged since modern antibiotics were revolutionized with the discovery of penicillin in 1928. And as their use has expanded, so has the likelihood of resistance.

Antibiotic resistance is a global issue that has grown in severity in recent years. In a landmark 2014 analysis called the “Antimicrobial Resistance Global Report on Surveillance,” the World Health Organization raised alarms on the growth of antibiotic-resistant organisms.

“Increasingly, governments around the world are beginning to pay attention to a problem so serious that it threatens the achievements of modern medicine,” the report summary states. “A post-antibiotic era – in which common infections and minor injuries can kill – far from being an apocalyptic fantasy, is instead a very real possibility for the 21st century.”

Dr. Joshua Clayton, state epidemiologist in South Dakota, said action to prevent resistance has been stepped up in recent years in the Rushmore State.

Doctors and nurses are being trained to watch for infections that appear to be resistant, and monitoring of such illnesses has been heightened, Clayton said. While trying to treat individual patients, medical professionals are increasingly aware of the need to keep the larger issue of resistance in mind.

So far, only one of the three antibiotic-resistant bacteria labeled as “urgent” by the CDC has been found in South Dakota, Clayton said. Beyond known cases of CRE, the state has not seen cases of the other two most worrisome resistant bacteria: Clostrium Difficile, known as C-Diff, and an antibiotic-resistant form of gonorrhea.

Clayton said CRE is particularly worrisome because it has the potential to create enzymes that make it completely resistant to antibiotics.

“You’re talking about CRE that in some cases has a higher mortality rate than Ebola,” he said.

According to the state Department of Health, Carbapenems are a group of antibiotics typically reserved to treat only the most serious infections, especially if the underlying infection was already caused by antibiotic-resistant bacteria. That makes CRE, which is resistant to Carbapenems, among the most antibiotic resistant of all known bacterial illnesses.

A few populations in South Dakota are at higher risk of contracting an antibiotic-resistant illness, Clayton and Hoffman said.

People who reside in long-term care facilities or who require frequent hospital visits face increased risk of exposure, as does someone who has a medication portal, a catheter, or an open wound, or who has been intubated, they said. Anyone who has an autoimmune disease or is immune-challenged for any reason is more likely to contract a resistant illness. Also, patients with diabetes, those who contract the flu and those with chronic lung problems are in high-risk categories, the doctors said.

Both doctors also lament a reluctance of drug manufacturers to pursue development of new, stronger antibiotics.

“They’re not as lucrative as other drugs they can produce,” Clayton said. “We are almost at this tipping point where new antibiotics coming into the market are fewer and far between, we have these organisms that are more and more resistant, and the concern is that we will not be able to effectively treat patients who are infected, and we may have antibiotics that are no longer effective.”

30 seconds to safety

When treatment options are limited or antibiotics fail, patients with bacterial illnesses and infections typically die of sepsis or pneumonia. In sepsis, the infection enters the bloodstream and can kill; in pneumonia, the infection attacks the lungs and can lead to death.

On a micro-level, medical experts say proper hand-washing is a critical component of combatting the spread of antibiotic-resistance illnesses. Frequent use of hand sanitizers and thoroughly washing hands for 30 seconds or more is the easiest, cheapest way for medical providers and patients to stop the spread of illnesses.

Meanwhile, doctors are being taught to use antibiotics sparingly and only when needed.

Hoffman said physicians can sometimes get lazy and prescribe antibiotics just to try something or to soothe a worried patient. He gave the example of a mother who brings her child in with a viral chest condition and leaves with a useless prescription for antibiotics.

“The doctor out of the goodness of their heart concedes and says, ‘I will put your child on a course of antibiotics,’” Hoffman said. “Can you blame the mother, or can you blame the doctor? Well, no. But we’ve got to educate the public about a number of basic things, including that viral illnesses are not treated by antibiotics.”

Clayton said the state uses a significant amount of its annual CDC grant money to create effective communication channels between medical providers, infectious-disease specialists and medical associations across the state.

“We use that money to provide education to facilities, to investigate drug-resistant infections, and put a focus on antibiotic stewardship,” Clayton said. “That money has helped us prepare and work with facilities.”

Medical providers are also taking the lead in sharing information about reducing resistance and the spread of resistant diseases.

The state is also home to the South Dakota Antimicrobial Stewardship Workgroup and another working group specifically focused on fighting the spread of CRE. Infectious-disease specialists from the three major South Dakota medical providers (Avera, Sanford and Regional), the state Department of Health and other infectious-disease experts will gather in Sioux Falls in October for an annual conference to share ways to fight antibiotic resistance. Nine medical professionals also volunteer as members of the state Infection Control Council.

Julie Meyer, lead infection-prevention specialist at Sanford Health, said her team works across the broad reach of the Sanford medical group to provide training and education in metro areas and small towns in South Dakota.

Meyer said doctors and nurses across the state are aware of the risks of antibiotic resistance, and if a resistant case is identified, an immediate focus is placed on seeing if patients have any commonalities that could indicate an outbreak.

“We have a flagging system so we can determine, ‘Is this an isolated case or do we have indicators of an outbreak?’” she said.

Meyer also urges medical patients to be proactive about their medical care and feel free to push providers when necessary about keeping things clean, including medical equipment they use.

“Be aware of what’s happening and ask questions,” Meyer said. “If you see somebody not washing their hands, you do have to be an advocate and let them know you noticed that. No nurse says, ‘I’m not going to wash my hands today,’ but sometimes we do need that little reminder.”