You pay it when you buy a pair of jeans, a couch or a loaf of bread. Many shoppers don’t even notice the small tax assessed at the bottom of the sales receipt.

But Margaret Straley does. And last month, the Sioux Falls woman’s explanation to lawmakers how the state sales tax affects her budget helped launch them into a heated multi-billion-dollar debate over how South Dakota collects taxes and about who pays and who does not.

The debate brought to light how more than $1 billion in annual sales tax breaks, or exemptions, overwhelmingly benefit the state’s largest industries such as agriculture, medical care, insurance and advertising. Lawmakers held a robust debate over those exemptions as they examined new options for state revenue.

Changing shopping habits and other factors have caused sales tax collections to stagnate in recent years and that trend could be costly for a state that in comparison to others has an outsized reliance on sales taxes to fund government.

Under the current system, for every dollar that South Dakota residents and visitors pay in sales taxes on groceries, household goods, home heating oil, hardware supplies, restaurant meals and consumer services, roughly a dollar of potential sales tax revenue goes unpaid by businesses big and small.

Straley, a 63-year-old office assistant, used a jar of peanut butter in a real-world example to illustrate the penalizing nature of the state and municipal sales taxes collected on food purchases, a highly regressive form of taxation implemented by South Dakota and only two other states.

Straley testified to a Senate committee that eliminating the 6.5 percent sales tax on a $25 food purchase would save her enough to buy another jar of generic peanut butter, “which is a meal for me with a piece of bread,” Straley said, her voice breaking.

The tax discussion unfolded against the backdrop of a U.S. Supreme Court case to be argued in April. South Dakota’s attempt to collect sales tax on online purchases is being challenged. If the justices uphold the state’s law, as much as $50 million could be added to sales tax collections annually.

Democrats who pushed the food tax exemption hoped to offset the resulting revenue loss with the money from new taxes on internet sales if the state wins the case.

In two committees, lawmakers shot down the attempts to end the food tax or phase it out as new internet revenues arrive. But the bills revived a long-standing debate over the reliance of South Dakota on the sales and excise taxes, which generate $1.4 billion a year and form nearly three-quarters of the state’s annual general fund revenues.

A regressive tax

Sales taxes are considered “regressive” because all consumers – rich or poor – pay the same tax rate on purchases. For example, the sales taxes in Sioux Falls or Rapid City would add $6.50 to a $100 purchase of groceries or other goods, creating an unfair burden on someone who makes $20,000 a year compared with someone who makes $100,000 a year. In that system of taxation, the poorest 20 percent of Americans pay almost 11 percent of their income in taxes, compared with the wealthiest one percent of taxpayers who pay only 5.4 percent of their income in taxes, according to the non-partisan Institute of Tax and Economic Policy.

South Dakota is the fourth most-regressive tax state in the nation, according to ITEP. In a recent study, the group reported that the poorest 20 percent of South Dakotans pay 11.3 percent of their income in taxes each year, while the wealthiest one percent of South Dakotans pay only 1.8 percent of their income in taxes.

Straley told the Senate Taxation Committee that she would directly benefit from a bill to exempt food from the 4.5 percent state sales tax and 2 percent sales tax collected by the city of Sioux Falls. An unexpected furnace repair this winter cut into her budget for food and forced her to limit what she ate and to eat dinners at The Banquet in Sioux Falls twice a week. She said the sales tax is a noticeable burden on her ability to buy necessities.

Sales tax rates for area states

Montana, no state sales tax

Wyoming, 4%

South Dakota, 4.5% (cities can add up to 2% more)

North Dakota, 5%

Nebraska, 5.5%

Iowa, 6%

Minnesota, 6.88%

Notes: In this group, only South Dakota fully taxes food; South Dakota and Wyoming do not impose an income tax.

Source: State of South Dakota

Supporters of the food tax say it is among the most stable of revenue sources because people will always need to eat. The food sales tax is also viewed as a way to broaden the state tax base and insulate South Dakota from larger economic forces such as the Great Recession of 2008.

The regressive nature of the state taxation system led to an impassioned plea for reform by state Rep. Elizabeth May, R-Kyle, who represents the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation and Oglala Lakota County, one of the poorest counties in the nation. May proposed a bill to close some major exemptions, which she called “carve-outs,” in order to replace revenues lost by exempting food sales.

“If we are not even responsible enough to look at the people that are receiving the sales tax exemptions, before we consider raising the taxes on the citizens of South Dakota, we have to ask ourselves, ‘Are we doing our jobs?’ May said.

That conversation highlighted the many exemptions that left more than $1.1 billion of potential sales taxes uncollected in fiscal 2015.

Some exceptions date back decades

State revenue data show that the 4.5 percent state sales tax paid by consumers topped $958 million in fiscal year 2017. Add in the sales taxes collected by cities, which can implement their own 2 percent sales tax, and the excise tax paid by construction contractors, and the tax collections rose to $1.44 billion in 2017. That figure makes up 72 percent of all state revenues. Of that, about $364 million is returned directly to cities that collect their own sales tax.

The true amount of revenue left uncollected due to the exemptions, state officials acknowledge, is likely much higher than the $1.1 billion estimate, because some businesses, including grocers, aren’t required to fully break down data on the exemptions they claim.

Many of the exemptions have been on the books for decades and are seen by backers as strengthening key state industries, avoiding double taxation on products used to make other products, and providing an incentive for businesses to operate in South Dakota.

Amid almost annual worries that sales tax collections have stalled or may fall, lawmakers in Pierre have held a number of committee hearings this legislative session discussing the lengthy list and high cost of the exemptions. State records show that sales tax collections have held fairly steady in recent years, but did not see a corresponding bump from the half-percent increase of the state tax in 2016 or from recent major construction projects such as development of the Dakota Access Pipeline.

At the same time, lobbyists for the industries that receive the sales tax breaks have come forward to defend the value of the exemptions and explain why they are needed.

Big money is at stake. In fiscal 2017, the state sales tax generated nearly $1 billion in general fund revenue, the municipal sales taxes led to collections of $364 million, while the 2 percent contractor excise tax on new construction or remodels brought in $107 million. No other state revenue source comes close, with a prepaid tax on cellphones for 911 services generating $13 million in 2017 and the state tourism tax generating $12.5 million that year.

Exemptions typically come about when an industry representative approaches a lawmaker and convinces him or her that the sales tax break is needed. If the exemption is passed into law, the Department of Revenue tracks the intent of the legislation and embarks on an educational campaign to let affected businesses and operators know they are exempt from the tax, according to Alison Jares, deputy director of the business tax division.

Agriculture, government, health care top list

The list of exemptions in South Dakota is long and varied. Agriculture is the largest and most costly in lost revenues with more than $406 million exempted in fiscal 2015. Livestock sales, animal feed, fertilizers and pesticides, fuels used on farms, electricity used to run irrigators, and even swine and cattle semen used in agricultural genetics are all exempted from sales tax.

The next largest group is government itself, which received $186 million in exemptions for purchases made by state and local governments, Indian tribes, and religious and private educational institutions.

The healthcare industry received $140 million in exemptions in 2015 for most purchases by non-profit hospitals and specialists including chiropractors, podiatrists and dentists. Medical equipment, prescription drugs and devices prescribed to patients are all exempted from sales taxes. Insurance companies received a sizable break, avoiding $121 million in sales taxes, including on commissions paid to agents, while financial services firms received $77 million in exemptions. No sales tax was collected on the sale of advertising by newspapers and TV and radio stations at a value of $21 million.

“When you buy the steak or the box of cereal or the pork chop or whatever, then you pay the sales tax. You don’t pay the sales tax every time a transaction is made within agriculture.” – Mike Held, lobbyist for South Dakota Farm Bureau

A few exemptions reveal the power of industry representatives to convince lawmakers that their businesses deserve a tax break. Rodeo operators received exemptions for the use of announcers, promoters and clowns to the tune of nearly $1 million in 2015. Sales taxes are not collected on the purchase of coins, currency or bullion. Sales tax is not collected on live game birds sold to commercial hunting operators; coin-operated laundries do not pay sales taxes on earnings; athletic officials at amateur sporting events are not charged sales taxes; and movie theaters don’t pay taxes when purchasing rights to show films.

Lobbyist Doug Abraham of Pierre, who represents the Motion Picture Association, said theaters shouldn’t be taxed on film rentals because sales taxes are collected on the movie tickets they sell. “This exemption is critically important to our industry,” Abraham said of the exemption valued at about $622,000 in 2015.

Some of the earliest exemptions, including on agriculture, charitable groups and non-profit hospitals, date back to 1939. A few have gone back and forth from taxable to untaxable over the years, including the rodeo and amateur sports official exemptions.

The at-times contentious conversation over sales tax exemptions this session came as lawmakers are keeping a close eye on the pending Supreme Court case. South Dakota is the lead plaintiff seeking to win the right to collect taxes on internet sales made to state residents by some companies located outside the state. The decision could come this summer and a ruling for the state could generate an estimated $13 billion for state governments across the country.

The complicated discussion over the sales tax exemptions is unlikely to fade anytime soon. In fact, a bill to require a study of the exemptions every four years passed through a House committee, but failed in the full House on a 34-31 vote in late February.

South Dakota is one of seven U.S. states without an income tax, making the Rushmore State heavily dependent on sales, use and excise taxes. Each year, a team of state forecasters crunches numbers to determine if or how much sales tax revenues may rise, thereby providing the governor an estimate upon which to base the entire annual budget plan.

To understand the revenue-generating power of the state sales tax, one only need to look back to 2016 when lawmakers looked to the sales tax as the only way to quickly generate money to raise the salaries of South Dakota teachers, who had the lowest average annual salary in the nation. After a heated debate and narrow vote, the state sales tax was raised that year from 4 percent to 4.5 percent, giving a raise to most of the state’s roughly 9,500 teachers.

During debate this session, Michael Held, a lobbyist representing the South Dakota Farm Bureau, laid out the major argument in favor of maintaining exemptions for the agricultural industry: farmers shouldn’t be taxed on sales of a product that will eventually be taxed when it is sold to the end consumer.

“Our philosophy is that the tax is collected when the agricultural item is sold,” Held said. “When you buy the steak or the box of cereal or the pork chop or whatever, then you pay the sales tax. You don’t pay the sales tax every time a transaction is made within agriculture.”

Held reminded the members of the committee that most lawmakers have farmers in their districts. He also said previous legislatures have studied the agricultural exemptions and found them valid, and that regular analyses are therefore not needed.

Other states provide exemptions

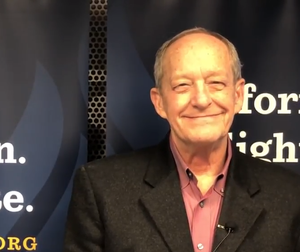

Rep. Ray Ring, a Democrat from Vermillion who is a retired University of South Dakota economics professor, said the state is on par with other states when it comes to allowing exemptions for major industries. Ring, who opposes the sales tax on food, said he supports many other exemptions that he said keep South Dakota competitive and the state economy robust.

Ring said closing exemptions could lead businesses to pass those new costs on to consumers, which could lower the overall tax base by reducing the number of taxed expenditures.

“We may raise more tax by removing some exemptions, but we may in the process discourage economic development and lower some of the rest of the tax base, so potentially we could conceivably be lowering our overall tax revenues,” Ring said.

Deb Fischer-Clemens, a senior vice president for Avera Health in Sioux Falls, argued against closing exemptions for non-profit hospitals. She noted that Avera paid nearly $8 million in sales, property and federal taxes last year while providing about $160 million worth of charity care, support of unpaid government programs and shortfalls in Medicaid funding.

“Avera is tax-exempt because of the many community benefits we provide,” Fischer-Clemens said.

She said Avera provides many services that do not generate a profit but fill a community need, such as helicopter service, community blood banks, transplant services and hospice care. “There are the things we would not be able to do if you change this tax structure,” she said. “Let’s not tax the sick.”

May’s bill to review the exemptions in full by 2023 and every four years thereafter passed through the Senate Taxation Committee in late February.

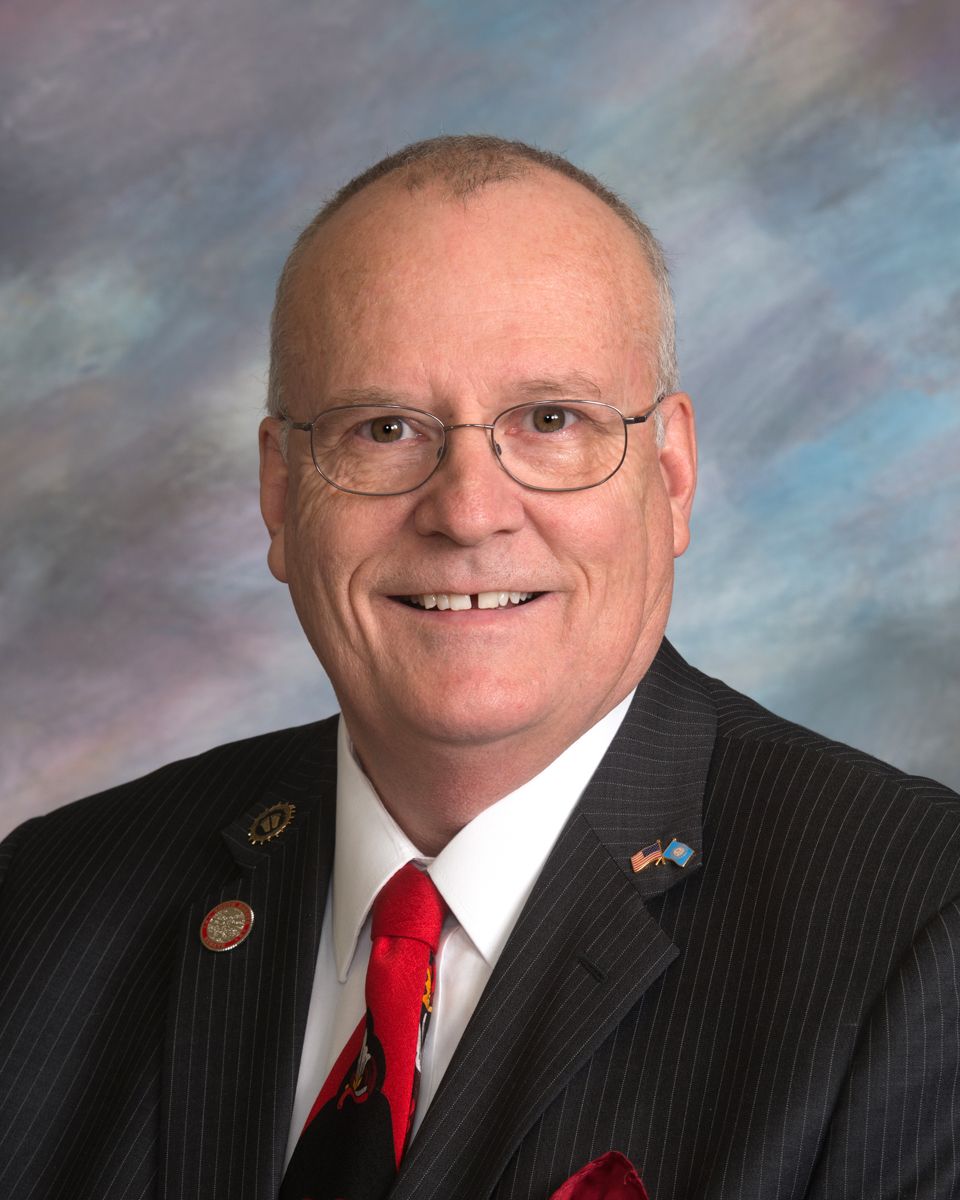

But such reviews, according to Sen. Ernie Otten and other veteran lawmakers, rarely result in the closure of exemptions. He and others point to a 2012 summer study which led to the closure of only one small exemption. Still, Otten said lawmakers should keep examining the exemptions because sources for new state revenues are limited.

“Somewhere along the line you’ve got to start drawing the line on exemptions,” Otten, R-Tea, a member of the Senate Taxation Committee, said in an interview. “It’s something that has to be revisited because this thing just keeps on growing and growing and I don’t know how fair to the citizens that is.”