South Dakota's four-year process to address the state's correctional needs evolved into a plan to build a new men's prison on 160 acres of farmland in Lincoln County between Harrisburg and Canton, with a price tag of $825 million.

That's when the drama really began.

Landowners near the Lincoln County site railed against the Department of Corrections for a lack of transparency during the search process.

Some lawmakers questioned the project's rising cost compared to comparable facilities in other states, urging more study for such a significant investment.

Supporters of the plan, including Gov. Larry Rhoden and his predecessor, Homeland Security Secretary Kristi Noem, insisted that the nearly 150-year-old South Dakota State Penitentiary in Sioux Falls needs to be replaced, and waiting longer will just make the project more costly.

It's a volatile issue, as might be expected for the most expensive publicly funded project in state history. Opinions on when, where and how to build a new prison depend on whom you ask.

To help sort it all out, News Watch sought different perspectives of some of the key people involved and let their views and experiences. Their stories will be told in a three-part series this week:

- This first part delves into the reasons for and against the prison in the first place. The current Corrections secretary is resolved it's the right project in terms of right place, but a former warden isn't so sure and said there's another more pressing need.

- Part 2, on Tuesday, features a judge, county commissioner and politicians.

- Part 3, on Thursday, features a family that worked the land at the planned prison site and their concerns on how the rural community will be altered.

Corrections secretary: 'My job is to deliver'

Kellie Wasko knew what she was getting into when Noem appointed her as South Dakota Secretary of Corrections in February 2022.

Her predecessor, Mike Leidhol, had retired in August 2020 after being placed on administrative leave as part of an investigation into allegations of sexual abuse and nepotism at the state penitentiary.

The Department of Corrections, which operates eight state facilities with about 3,800 inmates, was short on staffing and credibility. It was also running out of prison space, according to a consultant hired to prepare a statewide facility plan.

That report from Omaha, Nebraska-based DLR Group was released publicly about a month before Wasko took office, providing a road map to what became a priority for the Noem administration to address the state’s correctional capacity needs.

Wasko, who began her career as a correctional nurse in Idaho and served as deputy executive director of corrections in Colorado, serves as the point person for the executive branch mission – now under Rhoden – to bring the $825 million prison project to fruition.

In a one-on-one interview with News Watch at the South Dakota State Capitol in Pierre on Feb. 6, Wasko acknowledged that her role in the process is a "heavy lift."

“It’s an emotional subject,” said Wasko, 53, sitting in the House of Representatives gallery after testifying at a committee hearing. “Building a penitentiary of this magnitude is something that South Dakota has not done in any of our lifetimes. We’re building something that’s meant to last another hundred years.”

Staffing issues and clashes with prison industry employers have marred Wasko’s tenure at DOC. Critics such as Doug Weber, the former warden of the state penitentiary appointed by Gov. Bill Janklow in 1996, have questioned her grasp of the state’s correctional landscape.

But Wasko's background in correctional health services and focus on reducing recidivism has steeled her resolve in seeking change. She noted that the modern efficiencies of a 1,500-bed medium-to-maximum security complex would provide increased safety for staff but also expanded space for classrooms and counseling for inmates.

“It’s about building an appropriate facility that eases overcrowding, but it's also about putting that focus on rehabilitation while they're incarcerated,” said Wasko, who previously served as CEO of Denver-based Correctional Health Partners, a for-profit company that provides health care to prison facilities.

She pointed to South Dakota's rising incarceration rate and lack of commitment to justice reforms meant to help non-violent offenders receive alcohol and drug counseling and parole rather than prison time.

"There's been some give and take," said Wasko, whose department is now using prison capacity models that fit the national standard of the American Correctional Association rather than the previously cited operational capacity of DOC.

Critics such as an opposition group called NOPE said her department has had blinders on since targeting the Lincoln County site, ignoring concerns about the remote location and ballooning costs.

Wasko spoke at a meeting of the Lincoln County Board of Commissioners on Jan. 7, citing the authority granted her by House Bill 1017 in 2023 to purchase land and Senate Bill 49 in 2024 to begin site preparation and utility upgrades.

Her position was bolstered by a circuit court judge's ruling in October that granted the state's motion to dismiss a lawsuit from NOPE and individual landowners. That decision has been appealed to the South Dakota Supreme Court.

Wasko said that legislative appropriations for prison money were not tied specifically to the Lincoln County location, but that's where the site search led them.

“The authorization in statute allowed me as secretary of Corrections to buy the land,” she said. “I don’t think I've ever seen a situation where you would be (pigeonholed) into only purchasing land on a certain site. It was more like, 'You're able to purchase land, and make sure you do your due diligence.'”

“Due diligence” has become a buzz phrase for DOC as it moves forward with utility work and road planning at the site, preparing for construction that will come if legislators in Pierre approve the final funding piece.

Wasko acknowledged the consternation of those who live in the area.

“I appreciate it. I can appreciate where they live, that they lived in a community that was rural and had rolling fields and now there's a prison coming in. I can appreciate what they're envisioning. And my job is to deliver. I know what a prison looks like in a rural area, and so my job is to make this as informed as possible. It's a little difficult with a lawsuit in between us, so I'm looking forward to being able to get past that," she said.

Police chief: Sioux Falls services play a role

Long before he became chief of police in Sioux Falls, Jon Thum recalls touring the state penitentiary as a child around 1990 with his father, who served as prison chaplain on the hill.

“We would go to his office and be able to see into these different sections of the prison, and I remember thinking, ‘Man, this place looks old,’” said Thum of the quartzite-walled facility in northern Sioux Falls, which was built before statehood in 1881.

Thirty years later, Thum toured the prison as a police lieutenant preparing to provide logistical support for an execution. He saw crowded cells and crumbling walls as not just signs of an aging facility but as impediments to the aim of rehabilitating inmates so those released don’t resume a life of crime.

“Looking at it with adult eyes, you have a realization that it would be hard to get better or work on yourself in an environment where just living is a struggle,” said Thum, 45, who became police chief in 2021. “I've been consistent in my message that if we’re not talking about how to help people conquer some of their challenges, whether it's addiction or mental health or trauma they’ve experienced, we're not likely to see a better result when they get released.”

Sioux Falls, which successfully lobbied nearly 150 years ago to become the site of the Dakota Territory’s first prison, will still play a major role in the correctional process, Thum said. The new prison would be about 10 miles south of the state's largest city.

The DLR Group study found that the Jameson Annex, built in 1993 adjacent to the penitentiary, “is in good physical condition and operates in a secure and relatively efficient way.” Sioux Falls also is home to halfway houses such as Glory House and Arch Residential Treatment Center as well as behavioral health services.

“The reality is that the (Lincoln County site) is extremely close to Sioux Falls and there's aid that can be provided through partner agencies that have a big footprint in the city,” Thum said. “I don’t anticipate that the release plan (for inmates) is just to turn them loose into the next closest field. That’s not how it works."

As for the not in my backyard (NIMBY) component to the prison site objections, Thum said, “If you put it to a statewide vote, I think most people who didn’t have it in their county would vote for it to be (at the proposed location)."

Researcher: Rising prison rates are 'concerning trend'

Gov. Dennis Daugaard, who served as South Dakota's governor from 2011-19, addressed rising incarceration rates in his 2013 State of the State address, calling for justice and sentencing reforms.

“Our state faces a clear choice,” the Republican told legislators. “Down one path, we can continue to build prisons and allow corrections to consume an ever-increasing proportion of taxpayer dollars.”

The other path he outlined called for “justice reinvestment,” a rehabilitative strategy of drug and alcohol courts, counseling programs and probation options that would keep many nonviolent offenders away from prison cells.

The result of this effort was the Public Safety Improvement Act of 2013, or Senate Bill 70, which reduced juvenile corrections placements and temporarily slowed the increase in the state's adult prison population.

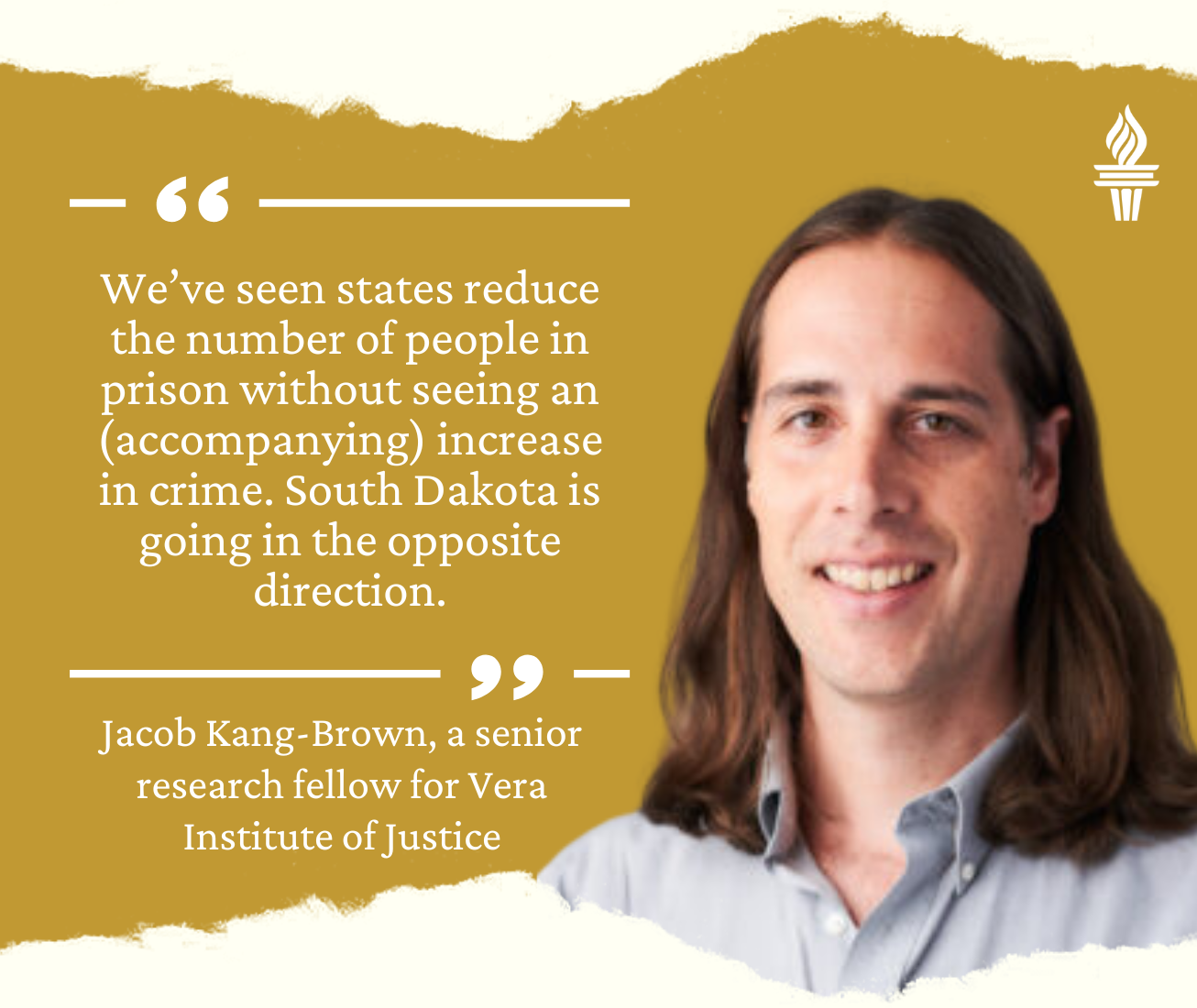

Now those inmate numbers are back on the rise, according to Jacob Kang-Brown, a senior research fellow for the nonprofit Vera Institute of Justice, which focuses on criminal justice reform.

South Dakota has a higher prison incarceration rate than the national average, with 660 people imprisoned for every 100,000 residents, compared to 576 nationally in the final quarter of 2023, according to the most recent data available.

The state's incarceration rate increased by 9.1% from 2022-24, the second-highest rate in the Midwest behind Wisconsin (9.2%) and one of the highest rates in the country. The national average was an increase of 1.6%.

“We’ve seen states reduce the number of people in prison without seeing an (accompanying) increase in crime. South Dakota is going in the opposite direction,” Kang-Brown told News Watch, noting that the state was well below the national incarceration rate as recently as the 1990s. “South Dakota now locks up more people than the national average, and that's a concerning trend.”

The reforms made during Daugaard’s administration left room for judicial discretion, and recent legislative actions have closed the loop on some of the policies that were seen as alternatives to detention.

The 2025 legislative session has seen Attorney General Marty Jackley push successfully to widen the list of offenses that are considered violent and result in time behind bars rather than presumptive probation.

South Dakota is also the only state in the country with a felony charge for ingestion of a controlled substance. A bill to make that crime a misdemeanor narrowly passed the Senate and will be heard by the House.

Kang-Brown sees attempts by some states to “arrest their way out of social problems” as troublesome down the road if not combined with efforts to combat recidivism.

“People across the political spectrum want real public safety, and I think the 'tough on crime' rhetoric can be a dead-end," said Kang-Brown, who holds a doctorate in criminology and law from the University of California-Irvine. "Almost everybody who goes to prison comes out again and is going to be back to being a member of your community and one of your neighbors. So states should really be investing in trying to find ways to meet the needs of people getting caught up in the criminal justice system.”

Former warden: Time for a 'pause' on prison project

Weber’s career in the South Dakota correctional industry spanned 32 years, including stints as chief warden and director of adult prison operations. There are few people as knowledgeable about the state penitentiary as Weber, who retired in 2013.

He thinks the aging Sioux Falls facility still has some life in it.

“My biggest concern is that they’re replacing the wrong prison,” said Weber, 70, who has been publicly critical of the Lincoln County prison project.

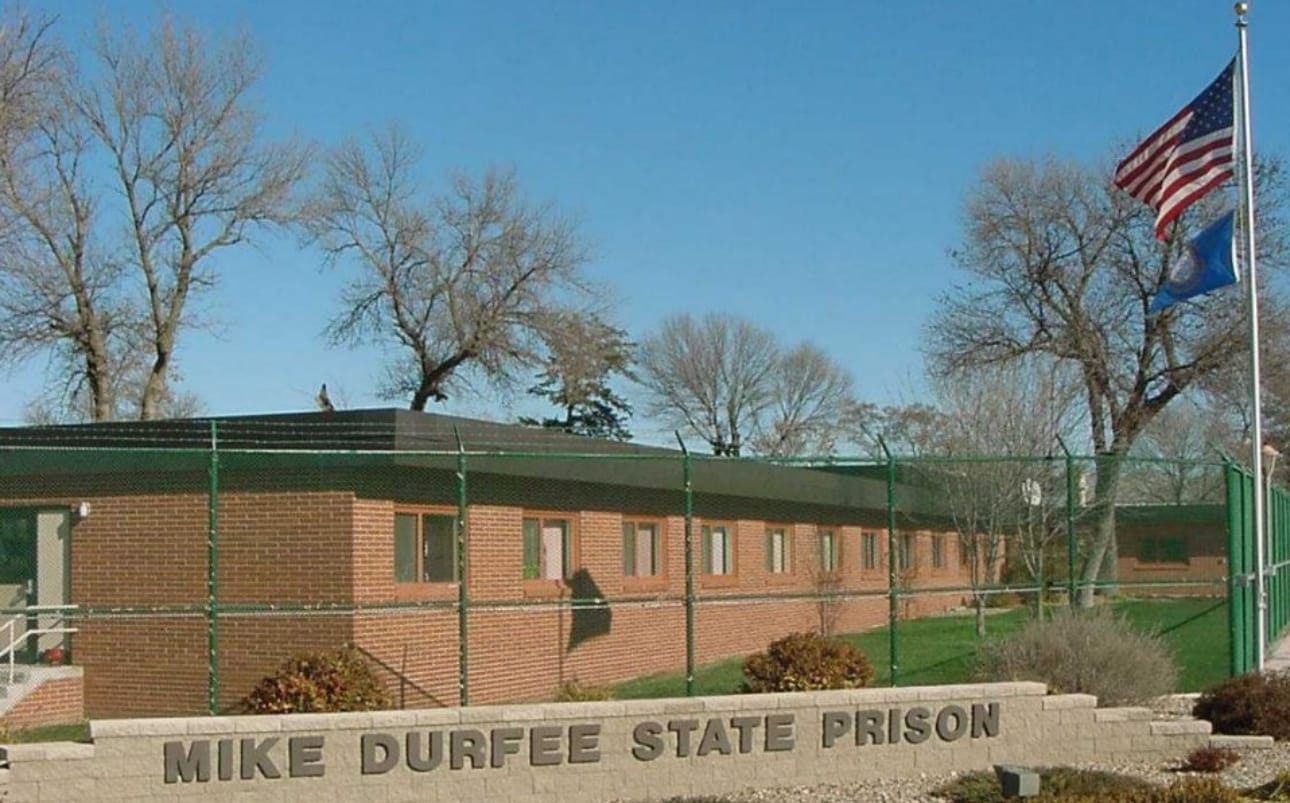

He told News Watch that the facility he’s concerned about is Mike Durfee State Prison on the former University of South Dakota-Springfield campus, 30 miles west of Yankton. That medium-custody prison currently houses 1,200 inmates, compared to 754 at the state penitentiary.

The buildings being utilized for housing inmates in Springfield were built as college dormitories and "are not conducive to a prison," according to Weber.

“It's stick-built like our houses, made out of lumber and nails and shingles,” he said of the Springfield prison complex. “So it's very susceptible to all kinds of things, including natural disasters or deliberate inmate actions. I understand that the state penitentiary is old, but it will never be blown down by a natural disaster. It will never burn down.”

Springfield Mayor Scott Kostal pushed back strongly on that analysis, telling News Watch that Mike Durfee inmates are "housed in brick and mortar buildings, built as college dormitories to provide safety from significant environmental events."

DOC officials have said that building a new prison in Lincoln County will help manage the number of inmates in Springfield, where violence flared over two days in July, with several injuries reported before order was restored.

Weber sees the design of Mike Durfee as a problem, not just overcrowding.

"There's no way to secure inmates in those dormitories," he said. "All the staff could do (during the violence last summer) was pull back to a safe area and allow the inmates to do what they were going to do and reinforce the perimeter to make sure there were no escapes."

Weber has called for a "pause" in the Lincoln County prison project to allow for more study on which facilities should stay or go. One of his ideas is to replace Mike Durfee with a new prison on state land in the Yankton area, relying on the Jameson Annex in Sioux Falls to provide maximum-security beds.

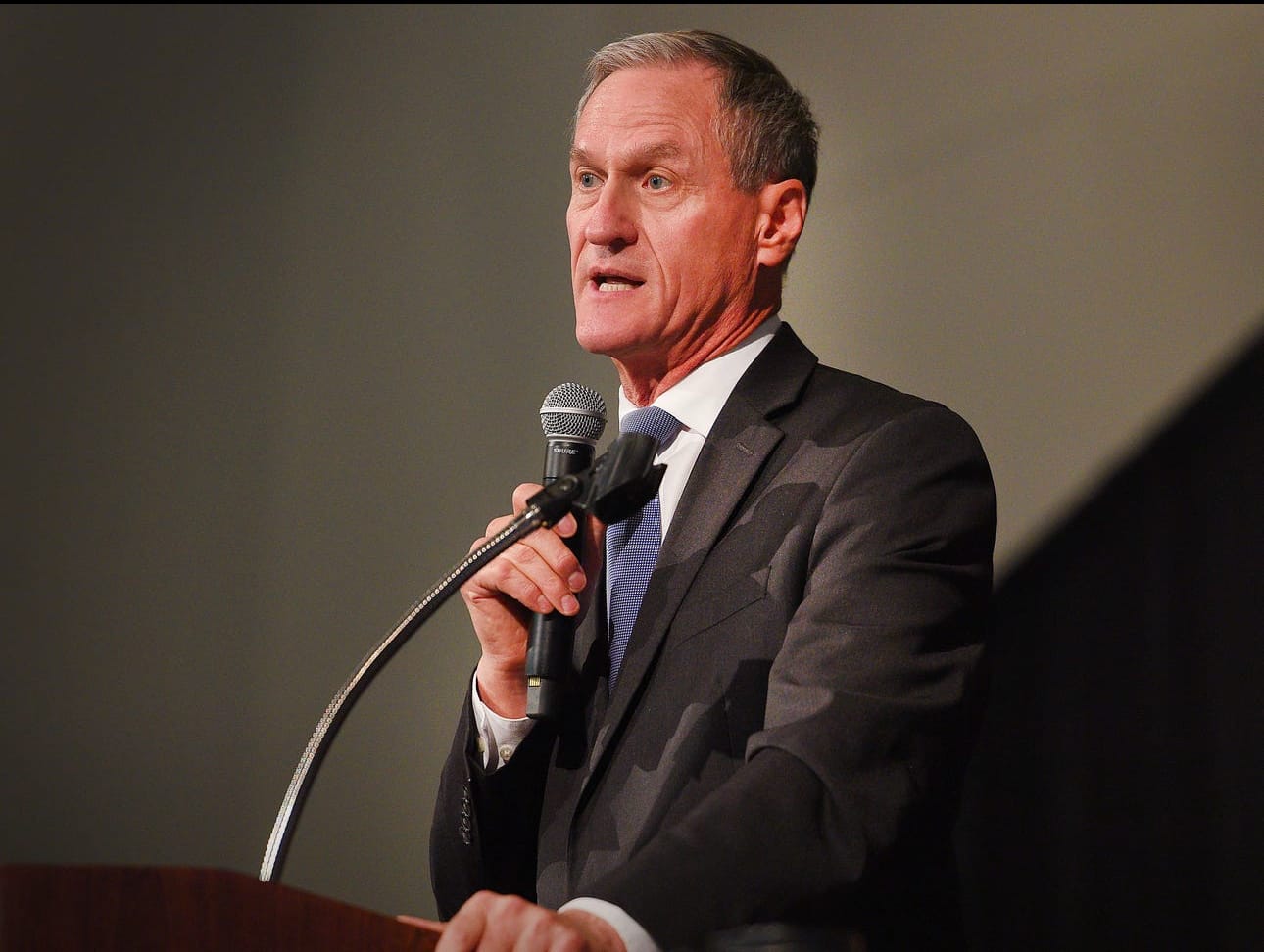

Gov. Rhoden bristled at a press conference when told that Weber doubted some of the more lurid descriptions of the state penitentiary's deterioration.

"Well, I won't disparage him," said Rhoden. "But I saw it for myself, and I know what I saw. So I guess that brings into question what his agenda is. I won't comment any further on that."

Asked why he waited until recently to publicly oppose DOC plans, Weber said that he realized the urgency of the 2025 legislative session as a proving ground for the project.

“It became really obvious that this was it,” he said. “If there was any hope at all of pausing this and doing something much wiser, the time is now.”

He has attended NOPE community meetings and traveled to Pierre to meet with Republican legislators. Asked about personal priorities, Weber told News Watch that he’s a resident of Lincoln County but lives in Sioux Falls.

“I’m a long way from that cornfield,” he said.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email every few days to get stories as soon as they're published. Contact Stu Whitney at stu.whitney@sdnewswatch.org