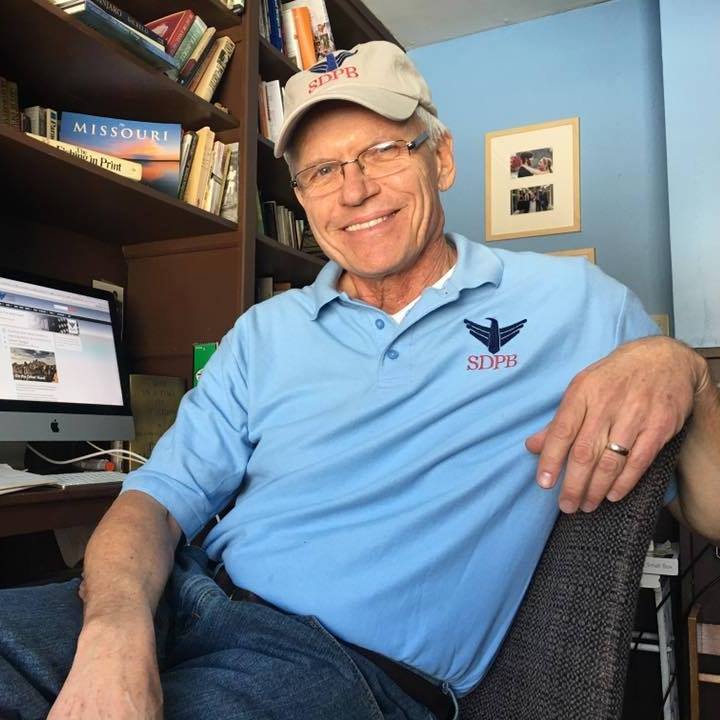

For more than 40 years, South Dakota journalist Kevin Woster has produced material for the state’s two largest newspapers, its largest TV station and for South Dakota Public Broadcasting, where he remains a writer and commentator.

Now semi-retired, Woster continues to report on a variety of statewide topics. And while he is a generalist in his journalistic coverage, his two main areas of focus have long been on state politics and the outdoors.

In both areas, Woster said, he has seen problems in the past few years in regard to openness and willingness of state officials to keep the public informed, particularly in the governor’s office and within the Game, Fish and Parks Department.

Woster is one of several media professionals interviewed by News Watch who said Gov. Kristi Noem and her administration have significantly reduced access of journalists to information and interviews over the past few years, despite Noem’s campaign promises to be the most transparent governor in South Dakota history.

“It seems to have gotten worse during her time in office. Things seemed to have tightened up,” Woster said.

More News Watch: Noem’s ‘demanding’ style sparks staff turnover, turmoil: ‘It’s a tough gig’

“She was a different politician when she was in the (U.S.) House of Representatives, more open and more inclined to focus on South Dakota issues rather than the hard-right themes. And I honestly believed her 2018 campaign pledge to be the most open of administrations. Maybe I was naive, or maybe she changed. Or both.”

Media members and experts interviewed by News Watch said that, in contrast to past administrations, Noem and others in state agencies have routinely denied interview requests, often refuse to answer simple questions about news topics or don’t return calls or emails.

Often, they require questions to be sent in emails that are responded to with brief statements rather than specific answers. Noem has also moved more toward providing public information in prepared statements or in highly produced videos rather than through back-and-forth discussion with reporters from well-established South Dakota media outlets.

Meanwhile, Noem continues to trumpet her openness. And in response to questions for this article, her spokesperson, Ian Fury, said that the governor has provided more information to the public than any of her predecessors and often relies on communication methods beyond the traditional media.

“There are many ways to communicate with the public directly; answering reporters’ questions is just one of those,” Fury wrote. “If reporters are unsatisfied with the answers that they receive, then they can always ask better questions.”

Lack of information on local level

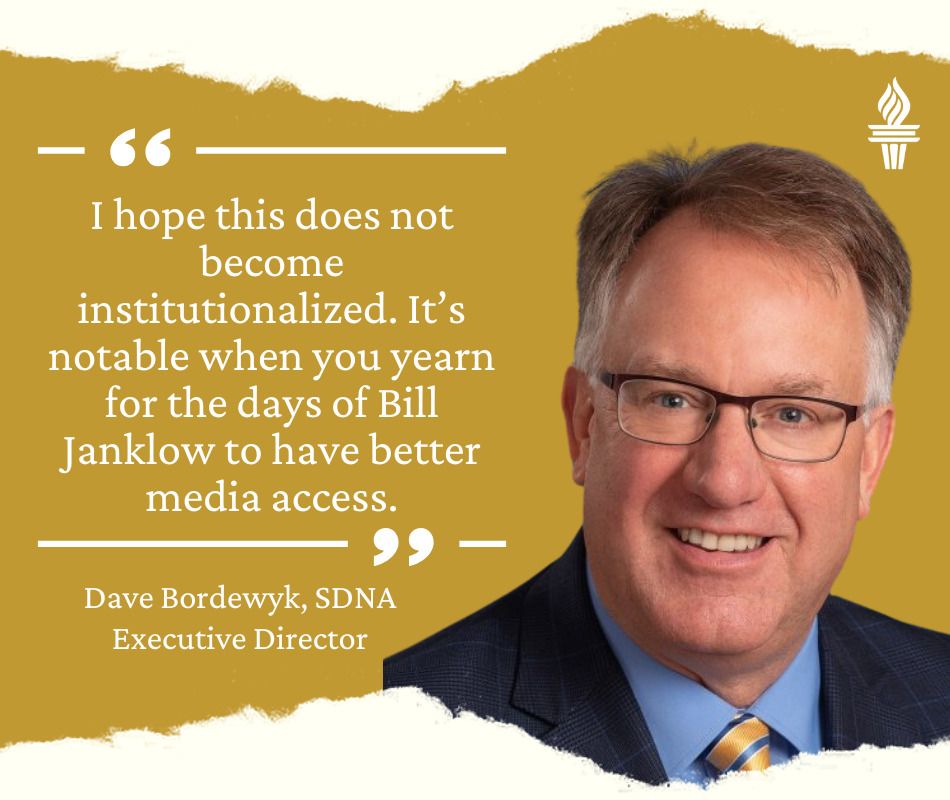

David Bordewyk, executive director of the South Dakota Newspaper Association, said he has heard from numerous members of the press saying it’s increasingly difficult to reach state officials in Pierre as well as state employees who do important work in their local communities.

According to Bordewyk, media members say that while many had developed good relationships with state officials, who were easy to reach and would speak openly with them, those relationships have faded or been intentionally curtailed under the Noem administration.

“The relationships between the press and public officials, being able to share information and to help tell a story, that’s not happening, even for things that are not a controversial topic,” Bordewyk said.

“What the editors are finding is that they put in a request for an interview at the local level and then it has to go all the way back to Pierre to get the OK before the local person can respond, or they don’t respond whatsoever. That has pervaded throughout state government at all levels, and local editors are frustrated.”

‘Public deserves’ more transparency from Noem administration

Woster said previous governors in South Dakota, notably Gov. Bill Janklow, would occasionally be at odds with a member of the media who reported negatively on their actions.

But Woster said he has never before seen such a blanket shutdown of media accessibility within an administration as he was with Noem over the past couple years.

Woster said other governors — including Republican Gov. Dennis Daugaard — took the approach that when it came to issues handled by officials and experts within state government, they provided wide latitude to those employees to speak openly with the public and news reporters.

The approach by Noem has not followed that tradition, and Woster said the state is not made better by restricting public access to information.

“Noem was right in promising to bring more transparency to state government. The public deserves it. The process of government deserves it. And the important issues involved in government deserve it,” Woster wrote in an email to News Watch.

“The closed-shop mentality that seems to have evolved in the Noem administration in the last few years looks particularly bad because it follows the commitment to openness during the Daugaard administration. I’m saddened by that, both as a journalist and as a South Dakotan.”

State agencies using social media instead

Fury, chief of communications for Noem, did not allow for an interview with himself or Noem but did send News Watch a statement in response to questions about media access to her administration.

“Gov. Noem is proud that her administration is the most transparent in history,” Fury wrote. “We communicate directly with the people of South Dakota, and the media is just one means of doing that.”

Fury wrote that Noem has published more material online than any prior governor, including through social media channels where Noem routinely releases written statements, photos of her travels around the state and nation and in crafted video messaging.

Fury said the governor answers reporter questions “at the appropriate time,” including at press conferences she holds at events, businesses and public meetings across the state.

Fury added that all state agencies follow the same policy in which media requests go through communications teams, which is done so other employees can focus fully on their own jobs.

“The people of South Dakota hear from the governor and state agencies directly through social media more often than any prior administration,” Fury wrote.

Government oversight ‘essential for democracy’

Michael Card, a political science professor at the University of South Dakota, said elected officials demonstrate a certain level of accountability when they regularly respond to journalists’ questions.

Local and state journalism outlets, he said, are where important issues and problems — and possibly corruption — are exposed, discussed and presented to the public for consideration and response.

“The public needs to be able to learn what their government is doing with some degree of detail,” he said. “Knowing what it’s doing and why is essential for democracy.”

Card, a keen observer of South Dakota politics and government for decades, said he is aware of reduced accessibility to information within the Noem administration and state government overall. One goal of limiting interaction with the media can be for officials who may be subjected to tough questions to reduce the influence of journalists by questioning their motives or challenging their integrity.

“I suspect that some message has gone out from the governor’s office to limit what they say to the press,” he said. “It’s just a distrust of the media, and it’s a larger message that is coming out from our former president (Donald Trump) and our governor, who speak much the same language.”

Card said some state employees may rightfully fear for their jobs if they speak to the media or say the wrong thing and draw the governor’s ire in any way.

Crafting a message

Card was surprised by Noem’s decision to travel out of state and not aggressively lobby lawmakers and the public amid the critical period of legislative consideration of her campaign promise to eliminate the sales tax on groceries, a measure that ultimately failed.

“There was a time during the legislative session where she was not accessible,” he said. “Especially when Gov. Noem was trying, or appeared to be trying to seek campaign contributions from out-of-state donors, she was simply not accessible.”

Card said he has noticed an increase in scripted, pre-packaged public messaging by Noem and a propensity of Fury, her spokesperson, to answer media inquiries with brief, sometimes snippy comments that are more provocative than they are useful to public discourse.

“I think we’re seeing more of those short, pithy statements from the governor’s spokesperson, and yet she’s not responding to questions,” he said. “They’re trying to create an image. And from their perspective, it may be best to say nothing.”

Card said he sees a downward trend nationally in the willingness of government officials to interact with media, and he said the decrease in accessibility is not good for the country or its people.

“I see a distance growing between what the government says it is doing and what it is actually doing, and I think that’s a real problem,” he said. “The public has a right to know and a need to know, and if the government is not responsive, then trust in the government is reduced.”

Noem approach reminiscent of Nixon and Trump?

In an email to News Watch, Woster said Noem’s relatively locked-down approach could be compared similarly with that of former presidents Richard Nixon and Donald Trump, both of whom at times vilified the media.

“Things seemed to have tightened up. There seems to be more of a siege mentality within the Noem administration, almost a Nixon-like enemies list,” he said.

“And the enemies seem, in a Trump sort of way, to be members of the mainstream media or outlets that have written or broadcast things the Noem crew didn’t like. Meanwhile, the hard-right national media seems always welcome and always played to (by Noem).”

The “suppression” Woster said he has seen under Noem, and heard about from other people he trusts, may be based in an unwillingness to admit that she or her administration might be in error or has miscalculated in some way.

“The idea that she might be wrong about something seems completely foreign to her, or, maybe worse, it seems foreign to members of her staff,” Woster said.

The shift to limiting access of the press and public to government information by the Noem administration has spilled over into the Game, Fish and Parks Department, an agency Woster has covered for decades and which has frequent touch points with the public and historically heavy coverage by statewide media.

Some state officials ‘worried about their jobs’

At a recent media panel discussion in Rapid City, Woster said he has never seen such reticence among GFP officials and employees to talk to the media. Many employees he knows are fearful that saying the wrong thing could cost them their jobs.

“I think the agency today is the least open, and its employees are the most worried about their jobs that I can remember,” Woster wrote to News Watch in a follow-up email.

Woster recounted a recent experience in which he attempted to report about fencing around a South Dakota trout stream. Woster said he wrote to the GFP spokesperson and waited nearly two weeks before receiving a useful response. He eventually emailed questions back and forth with a GFP official but was never granted an actual interview.

“I don’t think I’ve ever seen this kind of fear and this kind of suppression within Game, Fish and Parks that I’ve seen and heard about under Noem,” Woster wrote. “What we have now seems to be just an ongoing clamp down, as if reporters and news outlets who aggressively do their jobs are ‘enemies of the people,’” as Trump has called the profession.

Noem’s policy part of a national trend

The Noem policy of using public-information (PIO) or communications officers to filter media requests has become a more common practice in American government over the past couple decades, according to the Society of Professional Journalists, a top media trade group.

SPJ calls the practice “Censorship by PIO” and decries the method as a way for the government to control its messaging and prevent the press from accessing information or personnel within government.

“The restrictions have become, in great part, a cultural norm in the United States. They also have become an effective form of censorship by which powerful entities keep the public ignorant about what impacts them,” the SPJ reports on its website.

“This ‘Censorship by PIO’ works in tandem with other assaults on free speech including restrictions on public records, threats and physical assaults on reporters, prosecution of whistleblowers and threats of prosecution against reporters.”

In numerous surveys sent to reporters across the country, SPJ found that 75% of reporters who cover federal agencies say they must get approval from communications officers before being granted interviews and that a wide majority of reporters consider the PIO process as a form of censorship.

Some reporters also argue that the process of requiring all questions to be submitted in writing and responding via government spokesperson, instead of having interviews featuring active discussions between reporter and source, is another way that governments can avoid answering questions they don’t like. It also limits what information reporters can obtain, they say.

About 40% of PIOs surveyed by SPJ said they block access of some reporters to public officials based on prior reporting by those journalists.

Breaking traditions of the past

Bordewyk said he was disappointed when Noem ended the traditional practice of hosting weekly gubernatorial press briefings during the 2023 legislative session.

The briefings long served as a way for governors to update the state’s residents on progress about major legislation but also as a way for media members to ask probing questions.

“In all my years, I can’t recall a governor not holding regular press conferences during the legislative session, just like legislative leaders still do,” Bordewyk said. “That was unique, no doubt.”

Bordewyk said he hopes the reduced access to state government will be temporary and not become the norm. Bordewyk and others have said past governors, including Janklow, would occasionally limit press access but usually reverted back to openness when a crisis cleared.

“I don’t like what I’ve seen in the last several years in terms of the relationship between the executive branch and the press in South Dakota,” said Bordewyk, who has spent nearly 30 years as leader of the association that represents more than 100 daily and weekly newspapers across the state.

“I think it’s unfortunate, and my hope is that down the road it can be better, whether it’s within the next few years or beyond that,” he said. “I hope this does not become institutionalized. It’s notable when you yearn for the days of Bill Janklow to have better media access.”

Noem uses national conservative media

Bordewyk noted that much of the governor’s current communication strategy takes place on conservative national cable networks or through highly produced messaging on social media channels and not through contacts or interviews with local media.

In May 2019, the state agreed to pay $75,000 to a Massachusetts company, VideoLink, to install a video recording studio in the South Dakota Capitol that the governor has used to appear on national TV broadcasts, among other things.

Overall, taxpayers were on the hook for up to $130,000 in the first year of operation of the studio, according to state records.

Noem refused to participate in a fall 2022 gubernatorial debate hosted by South Dakota Public Broadcasting, with her campaign complaining that SDPB and National Public Radio had an “extreme leftist slant” in its news coverage.

Noem still makes a significant number of local appearances at events and in pre-arranged press conferences at locations across the state.

An internet search by News Watch revealed that Noem or her spokesman did not provide a comment or answer questions posed by reporters on deadline on 27 occasions between October 2020 and June 2023. The findings uncovered only those times when reporters included references to unreturned calls or email or when specific questions went unanswered.

Lack of access prompts public safety concerns

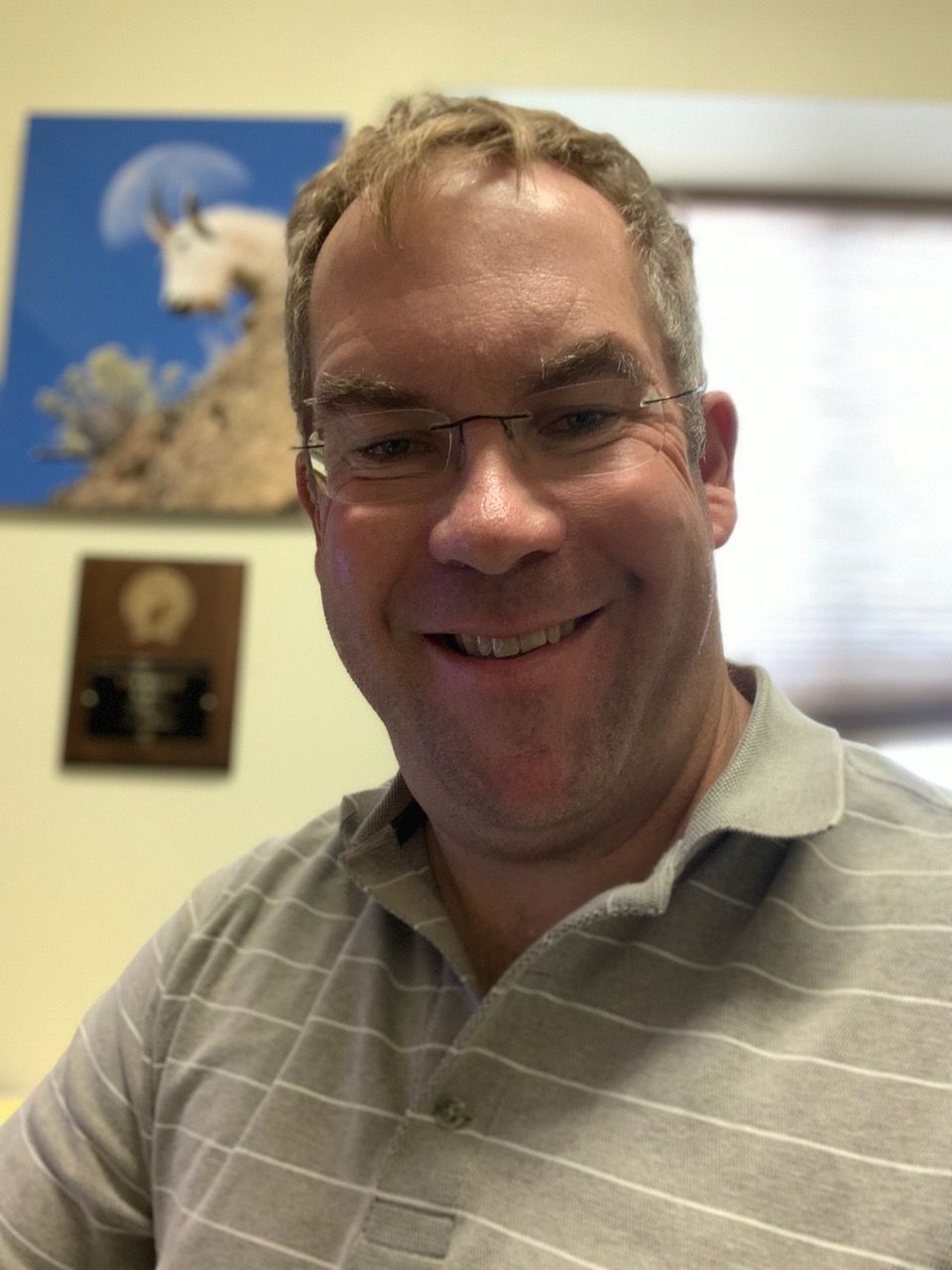

Mark Watson has spent the past 18 years at the Black Hills Pioneer newspaper in Spearfish, serving 15 of those years as editor, where he also frequently covers the outdoors and environment.

Watson said he has noticed a sharp decline in the willingness, or ability, of GFP employees to speak with him and his staff on the record. Watson said GFP employees he’s spoken with and interviewed for years, including some he knows on a personal basis, have recently said they are unable to speak with anyone from the media, and that all information requests must be in writing and sent to the main agency spokesperson, Nick Harrington.

Watson said the suppression prevented him from doing public-service reporting recently when a mountain lion was relocated from a residential neighborhood in Spearfish and when sightings of bears suddenly rose in western South Dakota.

Regarding the black bear article, Watson said he tried contacting numerous GFP staffers with no luck. After several days of phone calls and emails, Watson said he was granted an interview with a regional supervisor who was restricted in what he could discuss.

On the mountain lion story, Watson said he called a local GFP staffer to ask questions the day after the animal was relocated, but his request for an interview was denied. He was sent a generic statement late that day, and when he immediately replied to Harrington with follow-up questions about the mountain lion that was captured, he said he never received a response.

“There was no interview, and no conversation,” he said. “I’ve talked to a half-dozen to a dozen GFP staffers recently, including in the grocery store, and every single one said all questions have to be submitted in writing and that they have to get the governor’s office to sign off on the answers.”

Watson said he hoped the GFP would provide information to him and to his readers on taking steps to reduce the chance that bears or lions might enter their properties or public spaces.

For an article on chronic-wasting disease in deer, Watson said Harrington never replied to his emails.

“If we’re not able to get even a little bit of information from the GFP, somebody is going to get hurt,” Watson said. “The delay of information from official sources is, in a worst-case scenario, going to get somebody hurt.”

Watson added: “The state employees are generally great when we are able to talk to them. They, too, have told me that they are frustrated by their inability to discuss news topics with media.”

GFP responds to media ‘as appropriate’

Harrington, the GFP spokesperson, did not grant News Watch an interview.

He did respond to a series of questions with an email in which he said the GFP communications team is dedicated to providing customer service that includes communicating with the public through the agency website, social media accounts, print materials, emails, videos, podcasts and press releases.

He said the communications team responds to media requests “as appropriate.”

Harrington said the agency practice is to funnel any media requests through Harrington and the communications department as a way to keep in-field staff focused on their jobs.

“It is wholly within my core job duties to respond to media inquiries. It is not within the core job duties of staff in the field,” he said. “This organization is so that they have the flexibility to do their jobs, and they trust me to do mine.”

Harrington did not address specific questions related to whether there has been a shift in media access policy within the GFP or whether he believes he has done a good job of fulfilling media requests for interviews or information.

He did list a few occasions in which GFP has provided information to News Watch for articles related to the outdoors and GFP policy.

Harrington advised that media members and the public can engage with GFP through meetings of the GFP Commission, which meets regularly around the state, or by attending public hearings in person or virtually or by catching up on commission actions via state archives.

“Customer service is a key priority for our department, and we are dedicated to reaching our customers where they are, which includes through all these platforms,” Harrington wrote.

Month delay in response from spokesman

Beyond the GFP silence, Watson has had difficulty getting information from other state sources, including the governor’s office.

On June 2, Watson wrote to Fury with three questions about the governor’s announced deployment of National Guard troops to the Southern U.S. border. Watson asked about the number of Guard members deployed, what units they would be from and what their mission would be.

Fury replied by email that day saying he was on paternity leave and would reply by email.

On June 30, four weeks later, Watson received a response from Fury indicating that “further details on the deployment will be available at a later date.”

Watson also queried Fury about what he thought was a “gag order” placed on GFP officials regarding media inquiries. Fury replied that no such order exists, but that the administration’s protocol was that all questions to GFP must be presented to the agency spokesperson and not to individual employees.

‘Something has changed’ in Noem administration

Watson, who serves as the chairman of the First Amendment Committee within the South Dakota Newspaper Association, said he is troubled by the lack of accessibility of government officials and information.

“Something has changed, and I don’t know what it is, but it feels a lot like micromanaging,” he said.

Watson said the shift to reduced access to information is bad for the public and the state because residents rely on newspapers and other trusted local media to get facts and not opinions presented as facts, which is common on social media.

”We want to get the official source to make sure this indeed did happen, or if it did not happen,” Watson said.

“The state and local governments have a duty to inform citizens, and the best way to do that is through trusted and reputable news outlets throughout the state. The state should have a policy of maximum disclosure and minimum delays, and right now it’s, ‘We might get back to you and we might not.’”

Lack of basic checks and balances

George Vandel, a retired GFP official, said he has heard that the media have been kept at arm’s length by the GFP.

Vandel, who serves on the board of outdoors groups, including the South Dakota Wildlife Federation, said GFP Secretary Kevin Robling has continued the practice of holding monthly conference calls with outdoors leaders across the state.

But Vandel said he is concerned that officials from GFP and other state agencies are reluctant to discuss any issue that might make the state look bad.

“I don’t know what’s going on, but I suspect that this is an administration that doesn’t like bad news, so if it’s anything negative, they don’t want anybody talking to the news,” Vandel said.

“I don’t think there’s great openness to talk to the press right now, which is unfortunate because they’re spending the dollars of hunters and fishermen, and I’d like to think they could do a better job of communicating with them through the press.”

Vandel and Wildlife Federation President Zachery T. Hunke both said they have seen a recent decline in the importance placed upon input from their organization and the public when it comes to the GFP Commission, an appointed board that makes outdoors policy decisions in South Dakota.

Hunke said that in May, the commission voted unanimously to approve the sale of more non-resident waterfowl licenses, despite strong written and in-person public comment against the increase.

“Over 90% of comments were against the proposal, and then 100% of the in-person comments were against the proposal,” Hunke said. “And the proposal still passes unanimously, which makes me wonder if there is any checks and balances within our commission.”

Hunke said he also has heard from members of the media and others that information is harder to get from GFP.

“It just seems like a recurring problem,” he said.

South Dakota native shocked at lack of openness

Josh Linehan is a native of Brookings who returned home in December to serve as the managing editor of his hometown paper, The Brookings Register.

He came back after journalism stints in Florida and Maine, both states known for strong public records laws that allow for access to significant government information. Linehan has experienced a culture shock of sorts since returning to the Rushmore State.

“The difference is night and day,” Linehan said. “In Maine, we did a ton of freedom of information requests, and we would inevitably get material provided to us.”

Linehan said he has faced some challenges in getting public information from local officials in Brookings, but obtaining information from state government officials in South Dakota has been more difficult.

“I’ve found that when we get something sent by the governor’s office or anyone in Pierre, questions just are not answered,” he said.

“It seems like the standard operating principle is to just deny any request outright and then force you to keep drilling down and drilling down to hopefully get some information.”

Public’s right to know

Linehan recently filed a formal public records request to obtain information about calls made to the governor’s anonymous “whistleblower hotline” for complaints about higher education in South Dakota.

After a long delay, Linehan received a letter from the state denying the request, saying the complaints fell under a records exemption for correspondence to an elected official.

“I cannot imagine that the governor’s office created this hotline and it has not created one record subject to public records law,” Linehan said.

“I don’t need anyone’s name and phone numbers, but I believe we and our readers would like to know what kind of things are being said that could possibly affect South Dakota State University.”

Linehan has contacted an attorney to appeal the state’s ruling and hopefully reveal what types of complaints, if any, have been received.

“It’s a frustrating process because they’re the public’s records and the public has a right to know,” he said.

— News Watch reporters Stu Whitney and Abbey Stegenga contributed to this report.