South Dakota's plan to build an $825 million men's prison complex in rural Lincoln County has sparked clashes of opinion not just among nearby property owners but within different branches and levels of government.

A major legislative showdown is evolving in Pierre as state lawmakers and Gov. Larry Rhoden debate whether to pass the final funding piece to begin construction on the prison on farmland between Harrisburg and Canton.

Members of Lincoln County's Board of County Commissioners have been swept into the controversy, either fighting for county zoning authority or taking heat from residents for not speaking out more forcefully.

Arguments also reached the legal system due to the efforts of Neighbors Opposed to Prison Expansion (NOPE), a group of landowners that fought the state’s effort and sued to prevent the project from moving forward.

To help sort it all out, News Watch sought different perspectives of some of the key people involved. Their stories are being told this week in a three-part series:

- Part 1 delved into the reasons for and against the prison in the first place. The current Corrections secretary is resolved it's the right project in the right place, but a former warden isn't so sure and said there's another more pressing need.

- Part 2, this story, features a judge, county commissioner and politicians: Why the site was chosen, why an opposition group couldn't legally stop it and the continuing debate in Pierre.

- Part 3, on Thursday, features the family on whose land the prison would be built and how the original owners would react if they knew their farm was slated to be a prison.

Judge: Prison 'must be located somewhere'

Of all the opinions surrounding the decision to build a new prison on Lincoln County farmland, the most consequential was delivered Oct. 23.

It came in the form of a court decision from the Second Judicial Circuit, where Judge Jennifer Mammenga granted the state’s motion to dismiss a lawsuit from opponents of the project, including members of NOPE.

The ruling, since appealed to the South Dakota Supreme Court, was a blow to organized efforts to stop or delay construction. Those efforts were re-channeled to the legislative and public relations arena after Mammenga’s decision came down, nearly a year after the lawsuit was filed.

The crux of the complaint was that the state’s prison plans violated Lincoln County zoning laws and clashed with the county’s comprehensive plan.

The state argued that the landowners bringing the lawsuit lacked standing and the state was protected by the legal doctrine of sovereign immunity, which puts limits on when the government can be sued.

That doctrine in state law, according to judicial precedent, dictates that sovereign immunity exists when a state agent’s duty is discretionary (allowing for flexibility of action) rather than ministerial (rigidly following orders).

Mammenga characterized House Bill 1017 from the 2023 legislative session as allowing the DOC to purchase property for the prison but not mandating where or when to do it, calling the duties conferred by the law “discretionary and properly delegated."

As for the question of state authority versus county ordinances, the judge stated that “a county by its very nature is a legislative creation, and therefore seemingly lacks the authority to preempt state law.”

Mammenga, whose career as a prosecutor included a stint as Assistant U.S. Attorney in South Dakota, also addressed the imperfect process of any government entity seeking to find a suitable place to build a correctional facility.

Fair or not, she concluded, "not in my backyard" is not a legal strategy.

“Even if a balancing of interests is undertaken,” she wrote, “this Court finds that the likely result will be that the necessity of the construction of a new prison outweighs the interests of the surrounding landowners. A prison, like a jail, is a necessary government function, and it must be located somewhere.”

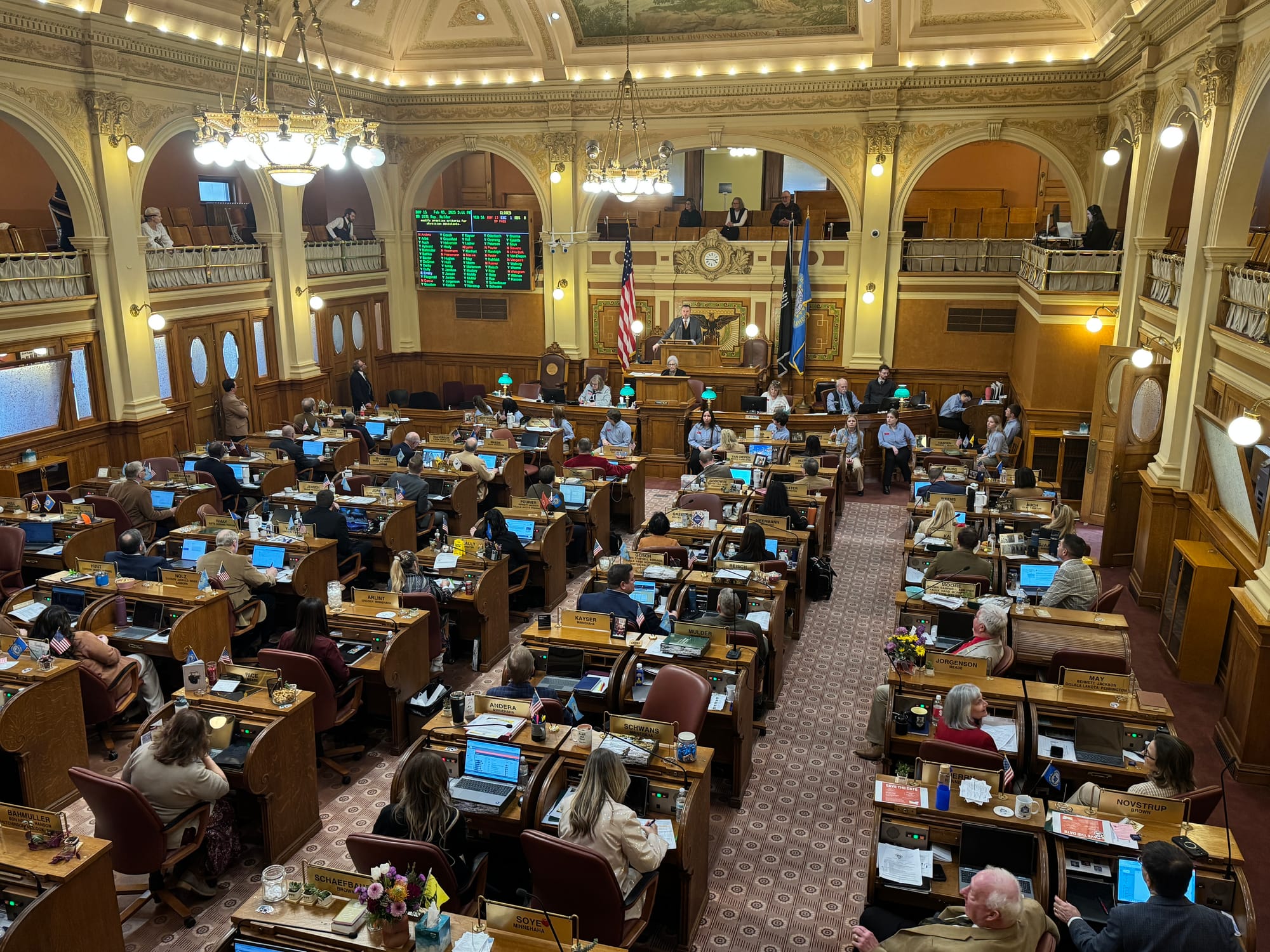

Lawmakers: 'It's not looking good right now'

On Feb. 5, moments after the House of Representatives adjourned for the day at the Capitol in Pierre, legislators Will Mortenson and Aaron Aylward walked down the hallway stride for stride.

Anyone who expected the Republican colleagues to be in lockstep regarding the state prison project, however, hasn’t been paying attention to party politics in South Dakota.

Mortenson, a Fort Pierre lawyer and former House majority leader, is viewed as part of the GOP establishment, with connections to U.S. Rep. Dusty Johnson. He supports House Bill 1025, which would provide the final funding piece to green-light construction on the chosen site.

Previous legislation has funneled $567 million into an incarceration construction fund (an estimated $643 million with interest), which means the commitment in one-time dollars from 2025 would need to be $182 million to reach $825 million.

"This has been four years coming, and if it's four more years, it's going to cost a billion dollars or more," said Mortenson. "If you think it's expensive now, just wait."

Aylward, a job recruiter from Harrisburg who represents Lincoln County, serves as vice chair of the South Dakota Freedom Caucus, which touts limited government and landowner rights as part of the party’s recent populist wave.

He staunchly opposes the funding bill, which would authorize the DOC to spend $763 million on prison construction on top of the $62 million appropriated last year to prepare the site and arrange for electric, sewer and water utilities.

"It's not looking good right now," said Aylward when asked about HB 1025 getting the two-thirds vote it will require from both houses to reach the governor's desk. "Things are so tight budget-wise right now that people can't justify going forward with this."

The bill suffered a setback on Feb. 12, when the House State Affairs Committee sent it to House Appropriations without an affirmative "do pass" recommendation, with ongoing operational costs one of the key concerns.

The legislative clash underscores challenges faced by Rhoden and GOP moderates as the party's populist wing flexes its muscles in leadership positions. Two of those leaders, Rep. Karla Lems and Sen. Kevin Jensen, represent District 16, which includes Canton, and are strident opponents of the prison plan.

Jensen introduced Senate Bill 124, which would establish an incarceration task force that, among its responsibilities, could "examine best approaches and potential alternative sites" for new and existing correctional facilities.

Supporters of the prison project said this research has already been done. They point to previous facility plans, task forces and summer studies that correlated prison expansion and modern efficiencies with aiding rehabilitative services.

"I've started to hear more from police chiefs and sheriffs and prosecutors who know that we need adequate facilities for incarceration and we need to do better on the corrections side, the rehabilitation side, keeping people out of prison," said Mortenson. "It's not money that anybody likes to spend, but it's our responsibility to get this done."

Gov. Rhoden: Finding prison site was 'gift from God'

The push for new prison facilities gained urgency during Gov. Kristi Noem's time as governor and is linked in many ways to her legacy, for better or worse.

The Legislature has already committed $87 million to build a new women's prison in Rapid City, with a likely completion date of early 2026.

In her final budget address Dec. 3, Noem spoke of the state men's penitentiary “falling down” and being older than the state itself, urging legislators to pass a final funding package so that construction on a new facility can begin.

Enter Rhoden, sworn in as the state’s 34th governor on Jan. 27, two days after Noem was confirmed as secretary of the Department of Homeland Security.

The Meade County rancher and legislative veteran faces a tough political scenario, especially with a likely run for re-election looming in 2026.

Populist groups touting landowner rights have become a rising political force in South Dakota, with the massive rural prison project one of their top concerns.

Rhoden must balance those objections with the fact that he was Noem's lieutenant governor and inherited the role as “chief wrangler” to push the final funding through the Legislature.

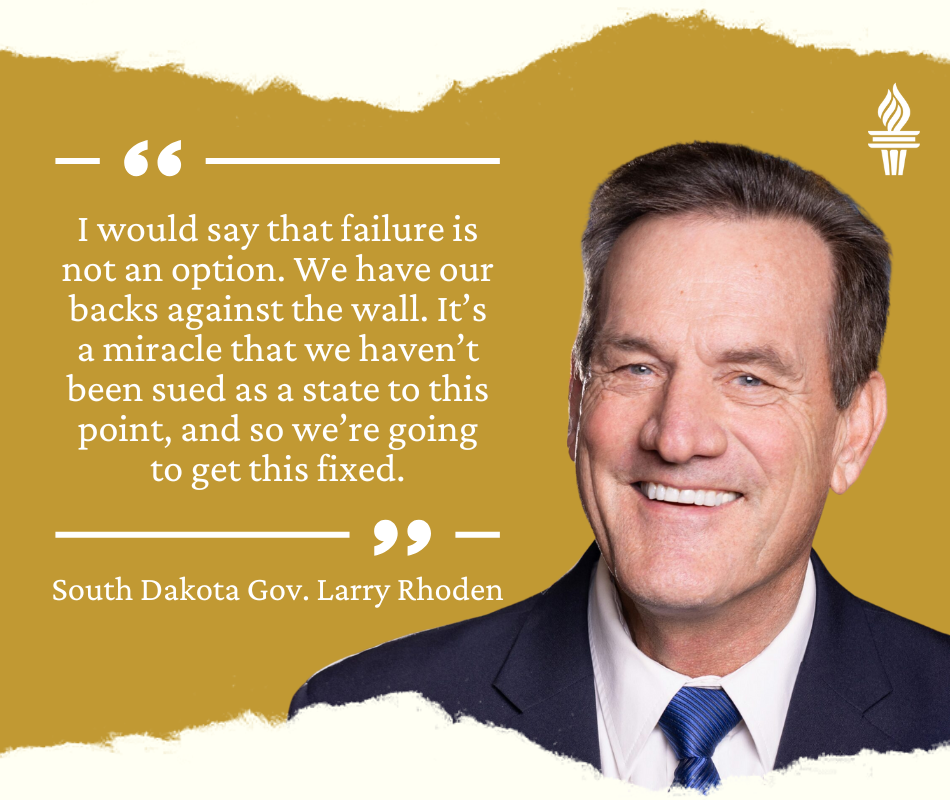

Any inkling that Rhoden would waver in this role was answered during his introductory press conference Feb. 6, when News Watch asked him about his approach to getting the bill passed and what happens if the effort falls short.

“I'm not prepared to discuss it not happening,” Rhoden said. “I believe that it will.”

He then encouraged any legislators who have doubts about the project to take a tour of the prison and outlined the “outdated and impractical” workings that he observed on a recent visit.

“We need to resolve that, and it needs to be this year,” said Rhoden. “I would say that failure is not an option. We have our backs against the wall. It's a miracle that we haven't been sued as a state to this point, and so we're going to get this fixed.”

He doubled down on those comments when meeting with the media Feb. 13, repeating DOC claims that it will cost the state $100 million to reverse course now due to inflationary impacts and money already invested in the site.

"Do we expect different results if we move to find a different area?" he asked. "There's always going to be opposition, regardless of where we site this. I thought it was a gift from God to find the site that we did that was appropriate for this prison relative to where it is now. And so that's what just kind of makes me sick to my stomach to think about starting over."

Policy analyst: No perfect science for site search

Before joining Noem’s staff as a policy adviser in 2022, Ryan Brunner served as commissioner of School and Public Lands, an elected position he held for eight years.

That experience came in handy when Brunner was called upon to help with a site search for a new 1,500-bed men’s prison on 160 acres within 20 miles of Sioux Falls, following the recommendation of a report from Omaha, Nebraska-based DLR Group.

The document provided a road map to what became a priority for the Noem administration to address the state’s correctional capacity needs.

The 18-month process included a request for information (RFI) directed at real estate agents and property owners, a callout for agricultural or industrial park sites that would satisfy the space requirements and be appropriate for what would become a sprawling correctional complex.

Brunner describes himself as a numbers guy, but he also knows his way around an acreage. His agricultural economics degree from South Dakota State University was enhanced by his experience growing up on a family farm and feedlot in Butte County.

He knew that trying to get a landowner to sell generational farmland so the state could build a prison was a longshot.

"You're looking for 160 acres, so you're not looking at commercial or residential," Brunner said of the state's 2023 property search. "You're looking at either industrial park land or you're looking at ag land. And a lot of farmers live next to where they farm, so they'd be selling land for a prison located close to where they're farming other property."

He noted that there was farm property west of Sioux Falls near Hartford "that we tried to buy for $70,000 an acre, and they thought we were buying it for the Minnehaha County Fairgrounds. And when I said, 'No, it's for the prison,' they weren't interested."

After months of seeking leads, Brunner helped identify a pair of 160-acre parcels between Canton and Harrisburg as land already owned by the Office of School and Public Lands through a 1992 property transfer by court order.

A previous prison-related land transfer served as precedent for acquiring the land. In 1984, Gov. Bill Janklow and the Legislature moved to close the University of South Dakota campus at Springfield and convert it into a minimum-security correctional facility, now known as Mike Durfee State Prison.

The resulting flurry of lawsuits against the state included one (Kanaly v. State by and Through Janklow, 1985) in which the South Dakota Supreme Court concluded that the transfer was constitutional if the Board of Regents trust fund was reimbursed for the full market value of the property.

That paved the way for the Department of Corrections to acquire the 320 acres in Lincoln County for the assessed value of $7.9 million in early 2024, using the spending authority granted by the Legislature a year earlier.

Half of that land, the 160 acres located south of 278th Street, is not planned for development as part of the prison project. DOC can use it at a later date.

At a Jan. 7 meeting with the Lincoln County Board of Commissioners, neighbors near the site accused the state of not adequately seeking other options closer to the interstate or in corridors that fit with the county's plan for land use and development.

Brunner disputed that assertion, saying the reason for doing the RFI was that "any real estate agent in the state could have found a location, signed up that owner, and then sold it to the state for a commission."

As for accusations that the state ignored leads pointing to landowners elsewhere in Lincoln County with plots for sale, Brunner told News Watch: "I've never had somebody reach out and say, 'Go talk to this farmer about this 160 acres.'"

The state did consider industrial park property in Lincoln County, he said, but it would have been more expensive and not immune to the same types of objections that the current site has inflamed.

When the DOC announced plans to build what is now the Rapid City Community Work Center in an industrial neighborhood in 2009, the state was sued by neighbors of the site who attempted to block the sale. That effort was unsuccessful.

County commissioner: 'Plant the flag and move on'

Jim Schmidt doesn’t see “establishment” as a dirty word.

The 83-year-old Lennox native has spent 27 years on the Lincoln County Board of Commissioners, making him the state’s longest-serving county commissioner. He still occasionally farms the land he grew up on.

Schmidt lives in Sioux Falls, where he attended Augustana University, served as president of Killian Community College and worked for the American Cancer Society of South Dakota. He served on the board of the city's chamber of commerce and is married to Teri Ellis Schmidt, longtime CEO of Experience Sioux Falls, formerly the Sioux Falls Convention & Visitors Bureau.

Those city credentials haven’t always ingratiated Schmidt with Lincoln County residents touting populist movements such as election skepticism and pipeline and prison site opposition.

His lack of public engagement regarding the state's prison project has angered members of NOPE and contrasted with county commissioners such as Joel Arends, who accused the state of running afoul of county zoning ordinances.

The commission voted in December 2023 to submit an amicus brief through the Lincoln County state's attorney in support of the landowners' lawsuit. But Schmidt and fellow commissioner Tiffani Landeen have otherwise stayed publicly neutral on the prison, and there has been no official county action.

"I haven't seen a single citizen walk up here in favor of this, but you guys just sit there and don't do a damn thing," county resident and NOPE member Jeff Spyksma told commissioners during public comment at their Jan. 7 meeting. "This is our lives. It's about time that you guys stand up for the county and not fold to the state."

Schmidt calls prison site opponents "good people" and said he empathizes with their cause. The fact that fast-growing Lincoln County includes the southern edge of Sioux Falls and communities such as Tea and Lennox also needs to be considered, he added, as developing and rural constituencies collide.

"You've got people up in Sioux Falls that I've talked to, and it's not that they're insensitive, but they think we need a new prison, so why not build it there? It's a good spot," Schmidt said. "And the people that live there, of course, say, well, of course they'll say that because they don't have to live next door to a prison. So you can understand how it seesaws back and forth."

Schmidt has had conversations with Toby Brown, the county's planning director, on establishing parameters for development if the prison is built, with increased vehicle traffic from employees and visitors leading to demand for convenience stores or hotels.

"We've discussed forming a development district if and when the prison is built to be able to regulate what kind of businesses crop up around a prison," Schmidt said. "We haven't formalized that yet, but it's one way in which you get ahead of the game rather than just reacting."

The irony is not lost on him that such forward thinking and communication is just what prison site opponents felt was lacking in the state's approach to Lincoln County. But he also sees the potential damage in tearing it all up and starting from scratch.

"No one wants a prison near them," said Schmidt. "But it's going to go somewhere, and someone is going to make that hard-nosed decision and say, 'Enough is enough, it's going to be here,' and they're going to plant the flag and move on."

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email every few days to get stories as soon as they're published. Contact Stu Whitney at stu.whitney@sdnewswatch.org.