STURGIS, S.D. – When he left the U.S. Marine Corps in 1983, after spending six years at Camp Lejeune in North Carolina, Ronald Lawson was a strong, healthy man with a barrel chest, strong arms and a solid frame that carried his 220 pounds with ease.

He was a roofer and mechanic who loved to fish and camp and spend days at a time enjoying the outdoors.

But roughly a decade ago, Lawson’s health and life began to change. In a period of about eight years, his knees and back gave out, he lost vision in one eye, he suffered severe stomach and intestinal pain, and he woke up one day with a lump the size of a goose egg in his neck that turned out to be Stage 4 throat cancer.

Lawson, who never smoked, was stunned at the pace and severity of his sudden illnesses.

“I was never sick a day in my life, and cancer doesn’t run in either side of my family,” he said.

During a recent visit to a Veterans Administration hospital in Sturgis, a doctor asked Lawson if he spent time at Camp Lejeune. In an instant, the doctor’s question dovetailed with all the TV commercials Lawson had been seeing about veterans who served at Lejeune and are suffering from cancer and other serious sickness.

The ads are sponsored by attorneys who are seeking clients who spent time at the North Carolina base from 1953 to 1987 and were known to be exposed to drinking water contaminated with toxic substances.

“I suddenly knew where all my problems had come from,” Lawson, 65, said from a couch in the one-bedroom subsidized Meade County apartment where he spends most of his time. “The toxic water caused my cancer and all this stuff, there’s no doubt about that.”

‘A shell of a man’

Lawson’s physical condition continues to worsen.

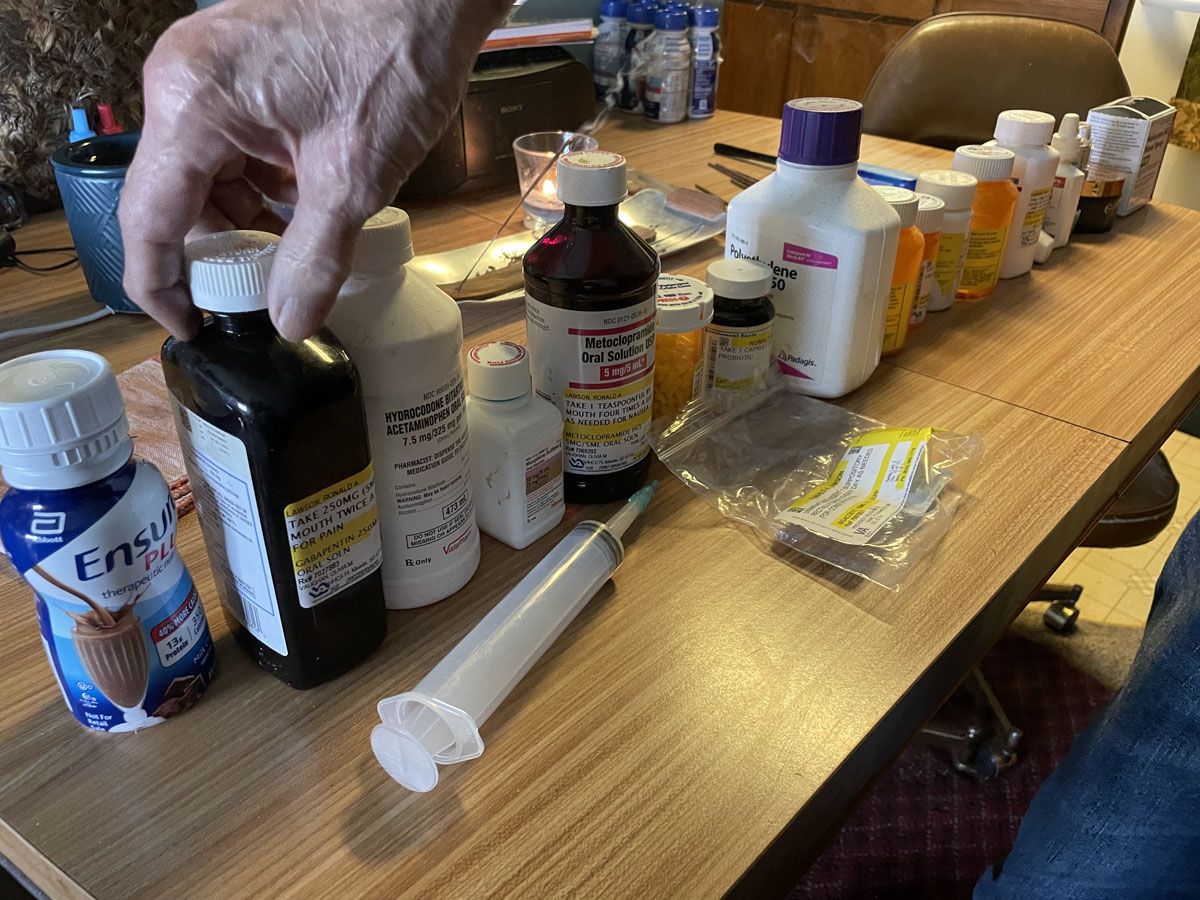

He speaks in a growl that is hard to understand because radiation damaged his vocal cords. He weighs only 130 pounds and is frail from nerve damage throughout his body. He cannot eat or swallow normally, so he consumes half a dozen bottles of Ensure protein drink through a portal in his stomach each day. He takes 19 medications twice a day for pain, to sleep and to prevent constipation and other side effects from his medication regimen.

“I’m a shell of a man now,” Lawson said, taking a sip of soda with shaking hands.

Next up, Lawson will learn if he has Parkinson’s disease, another condition caused by the water at Camp Lejeune and which could be the cause of his increasing instability and shaking.

More SD News Watch: veteran denied benefits after exposure to toxic burn pits

Lawson has contacted the Sokolove Law Firm and hopes for a financial settlement, which has been approved by the U.S. Congress to compensate military veterans and civilians. The federal government acknowledges they were sickened by the toxic water at Lejeune.

Despite that assurance, Lawson isn’t sure if he will ever collect.

“They say it might be settled in two years, but I might not be alive in two years,” he said.

Dry-cleaning chemicals in Camp Lejeune water

The federal government, and now Congress, have essentially acknowledged without qualification that people who spent 30 days or more at Camp Lejeune or nearby Marine Corps Air Station New River were exposed to toxic chemicals that entered into water treatment plants at the bases.

According to the federal Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry, an arm of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, the contaminants came from a dry-cleaning company near the bases and leached into two water systems there.

In a statement on its website, the agency concluded that “past exposures from the 1950s through February 1985 to trichloroethylene (TCE), tetrachloroethylene (PCE), vinyl chloride, and other contaminants in the drinking water at Camp Lejeune likely increased the risk of cancers (kidney, multiple myeloma, leukemias, and others), adverse birth outcomes, and other adverse health effects of residents (including infants and children), civilian workers, Marines and Naval personnel.”

When the water toxicity was discovered in 1982, the agency reported that PCE levels in drinking water supplied to the base and family housing had 1,400 parts per billion, about 280 times the safe level of 5 ppb. The level of TCE found was 215 ppb, or 40 times the safe level, the agency said. The agency said benzene, vinyl chloride and dichloroethylene (DCE) were also present in the camp water.

According to the VA website section on Camp Lejeune, veterans and civilians may qualify for medical coverage or compensation payments if they served or lived a month or more at Camp Lejeune, were not dishonorably discharged and suffer from one of a long list of presumptive illnesses that include numerous cancers as well as female infertility, miscarriage or in-utero conditions. The site also includes information about how to apply for health coverage or payments.

Camp Lejeune part of PACT Act

In 2022, Congress passed the Camp Lejeune Justice Act, which was part of the larger Promise to Address Comprehensive Toxics Act (PACT Act). It gave military veterans and civilian employees the ability to sue the government to obtain medical benefits and financial compensation for injuries or illnesses suffered due to exposure to toxic substances in the line of duty or work.

The act expanded the number of qualifying illnesses and added new categories of potential claimants, including those exposed to the defoliant Agent Orange and, more recently, veterans exposed to toxic burn pits in Iraq and Afghanistan.

President Joe Biden signed the act, which also prevents the government from making its usual claims of immunity.

Republican U.S. Sens. John Thune and Mike Rounds of South Dakota initially opposed the expansions within the PACT Act, but both eventually voted in favor of the measure.

While pointing to logistical concerns over implementation of the PACT Act and potential costs, U.S. Rep. Dusty Johnson, R-South Dakota, voted against the program, which could cost $280 billion over the next decade.

In a written statement sent to News Watch, Thune said he supported the act after amendments made by GOP colleagues made it tenable. Both he and Rounds earlier told News Watch they were concerned if the current VA system could handle the influx of new PACT patients.

“Veterans pledged their lives to the service of our country and they took upon themselves the burden of defending liberty for the rest of us. We must stand behind our promise to care for them when they return home,” Thune wrote.

Rounds also sent a statement to News Watch, offering much the same sentiments.

“I supported the PACT Act and a provision within the law that provided long overdue relief to former service members, their families and staff who were exposed to contaminated drinking water and toxic materials at Camp Lejeune. Those who have been impacted served our country honorably and suffered far too long,” Rounds wrote. “As a member of the Senate Committee on Veterans’ Affairs, I remain committed to making sure these men and women receive the care they have earned. While this law is not perfect, it was a step in the right direction. I think improvements can continue to be made.”

‘What’s the value of a human life?”

Attorney Patrick R. Burns was born in Vermillion, grew up in Sioux Falls and has a law degree from the University of South Dakota. He now practices in Minneapolis.

He’s also a former U.S. Army lawyer licensed in South Dakota, North Dakota, Minnesota and Wisconsin and so far has about 260 clients who are part of the Lejeune class action suit.

His clients suffer from a variety of illnesses, and some lost children due to the contamination, he said. One client group includes a father, mother and their child.

Burns said the government will use a formula to determine potential settlement offers, which he said could range from the tens of thousands of dollars potentially up to millions.

“There’s tens of thousands of people affected by this,” he said. “What’s the value of a human life that has been cut short or altered?”

Like other lawyers handling Camp Lejeune claims, Burns will take 40% of financial settlements provided by the government, which he said is common practice in product liability or negligence cases in which attorneys work on a contingency basis.

Family legacy of service, and injury

Gene Ridenour, 73, is part of a classic American military family.

His late father, Gene Ridenour Sr., served in the Army in World War II. Gene served as a Marine in Vietnam. His son, Gene III, won a Bronze Star for valor as an Army intelligence officer in Iraq in 2009.

Ridenour, a native of Sioux Falls who still lives north of downtown, enlisted in the Marines and served as a machine gun operator during the Vietnam War for part of 1968 and all of 1969. He was stationed at Camp Lejeune for about six months after he returned from combat.

Several years ago, Ridenour lost use of his leg, which he attributes to diabetes brought on by exposure to the toxic defoliant Agent Orange during his service in Vietnam. Since then, he has made his way around with a prosthetic aid.

But in 2015, Ridenour noticed a new health problem while using the restroom at a Hy-Vee grocery store and seeing that his urine “was as red as ketchup.”

Ridenour was diagnosed with a bladder infection, but the trip to the doctor led to a further diagnosis of bladder cancer, among the most common cancers related to the toxic water at Camp Lejeune.

Ridenour had bladder tumors removed and received chemotherapy.

‘Who’s going to fight for them?’

Ridenour said he signed up for the Camp Lejeune settlement to learn more about what happened at the camp and possibly to receive compensation, though he isn’t holding out hope for a major windfall.

“I don’t give a damn if I get money or not, to be honest with you. And if I did get money it would probably be taxi fare or something because the lawyers are going to take all of it,” he said.

Ridenour said he feels terribly for veterans who drank toxic water but even more so for the women and children who lived on the base.

“Think of all the married women who had babies and the civilian workers who were on that base,” he said. “They all drank the water, obviously, and who’s going to fight for them?”

Ridenour said he still supports the Marine Corps, but he is angry with the federal government.

“I’m mad because they should have known, and somebody screwed up,” he said. “I’m pissed off because all these years later, you find out about this stuff. We are Vietnam veterans, and we served honorably, but I’m not proud of the way they treated us.”

VA benefits not affected by Camp Lejuene settlement

Burns, the Minneapolis lawyer, said some potential clients are afraid of suing because they’ve been misled or inaccurately told that a settlement related to Lejeune could jeopardize future VA benefits. Some also believe they may be forced to repay the government for coverage already received, he said.

Past, current and future VA benefits will not be affected by a Lejueune settlement, he said.

Burns said the U.S. Navy Judge Advocate General Corps has been tasked with handling the Lejeune cases, but staffing and technology issues have slowed claim processing.

He said he hopes that even with a large number of claimants, affected people should begin to see settlement offers and possibly payments by the end of 2023 or early 2024.

“It’s not the lawyers or the injured people that are delaying it. It’s on the government side,” Burns said.

Despite any logistical delays, Burns said the Lejeune restitution law should lead to fairly rapid settlements, as it largely takes away the need for clients to prove their illnesses are caused by toxic water.

“What’s unique about this law is that it really reduces the typical causation and liability elements associated with most mass tort cases,” he said. “There’s no fight about how it happened. If you can show you were there and you have these certain illnesses, there’s a presumption it was caused by consuming the water.”

One day in church, next day ‘trained to kill’

John Ercink, 76, grew up on a farm near Claire City in the northeast corner of South Dakota.

Ercink knew he was about to be drafted and enlisted in the Marine Corps after graduating from New Effington High School. He was sent to Vietnam in June 1966, where he served more than a year as a heavy artillery operator who also did foot patrols as a rifleman.

“When I got out of high school, I was going to church and church programs, and the next thing I knew I was going to Vietnam as an 18-year-old who the Marine Corps had trained to kill,” he said.

Ercink said he experienced the worst of war while in Vietnam, including the death of close friends.

Upon return to the States, many veterans were harassed by anti-war protesters, and Ercink began to suffer Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, both from his time in war and from the war at home.

“We got shot up all the time. And as you first come back, you try to push this stuff away from you. But I can never forget that country and what it smelled like, and what the war was like and what blood smells like,” he said. “And then the protesters hated veterans. They were protesting not against the war, but against the warriors, throwing things at you, and it put a lot of stress on us.”

After a 30-day leave spent back home in South Dakota, Ercink was sent to Camp Lejeune, where he lived for about six months in barracks on the base, drinking and bathing in toxic water.

“You take orders when you’re in the service — you go where they send you,” Ercink said. “You can’t say, ‘I’m not going there, because the water isn’t safe to drink on the base,’ you just go.”

‘I came back not so healthy’

His war memories, coupled with exposure to the defoliant Agent Orange and then the toxic water at Camp Lejeune, have left Ercink with a host of medical conditions.

He has nightmares and restless leg syndrome that make it hard to sleep, constant ringing in his ears, neuropathy that has damaged the nerves in his legs and feet, and he has had both colon cancer and prostate cancer. Ercink said he also had part of his colon removed and had radiation for prostate cancer, and is doing somewhat better and still working his land.

And while he can’t be sure that toxic water at Camp Lejeune is to blame for his cancer, Ercink notes that neither form of cancer runs in his family.

“Like I say, I was a healthy young man when I went into the service, and I came back not so healthy,” he said. “I’ve got all this medical crap going on and it sure wasn’t from farming. It was all related to the toxic water or exposure to chemicals during the Asian vacation as we called it, the 13 months spent in Vietnam.”

After his honorable discharge from the Marines, Ercink returned to Roberts County where he farmed and owned a gas station before retiring. He has three children and eight grandchildren and lives near Lake City, S.D., with his wife who is his constant companion.

Ercink called the Sokolove Law Firm of Minnesota after seeing a TV commercial about toxic water at Camp Lejeune, and he has shared his military and medical history with the firm.

While he believes the lawyers involved in the class action suit deserve about 20% of any settlement and not the 40% they will likely take, he hopes to get a financial settlement to supplement the small VA disability money and Social Security income he receives each month.

“It’s hard to make ends meet with the income I’ve got,” he said.

Ercink said he doesn’t spend time placing blame for the mistakes that led to the contamination at Camp Lejeune. But he remains angry that more care wasn’t taken to protect veterans and civilians who served their country.

“I’m ducking bullets for 13 and a half months, and I was hoping to go back to civilian life, and then I get exposed to toxic water?” he said. “If there was toxic water there that long, somebody was not checking things responsibly, and I sure hope they’ve learned something from it.”

Lawson to go down fighting

While Lawson, the Marine from Sturgis, predicts he may not live long enough to see a settlement, he said that if he were to receive any money, he would travel to be with his extended family in North Carolina.

“I’m not able to do a lot anymore, but I’d move back home to be with my family before we all die off,” he said.

Lawson holds no hard feelings toward the Marine Corps, which he still loves. But he’s angry that people in the federal government didn’t do more to protect people living and working at Camp Lejeune.

”Somebody in the government knew about this and didn’t do anything about it, which is pretty depressing,” he said.

While Lawson is angry over his exposure to toxic water, he refuses to give in to bitterness.

“I drank, bathed and ate food cooked in that contaminated water, and I’m mad as hell about that,” he said. “But what are you going to do about it? Sit here and complain every day? That isn’t me because I consider myself a strong man and I’m not going to go down to that level. You’ve got to live the life you have as best you can.”