The elimination of birthing services at Winner Regional Health hospital on Saturday will force dozens of expectant mothers in a wide swath of south-central South Dakota to drive one to two hours on rural highways to give birth under the care of a doctor.

Ending the hospital's labor and delivery services on Feb. 1, 2025, came only after "a lot of tears and sleepless nights," but the difficult decision was ultimately the correct one, said hospital CEO Brian Williams.

The high cost of the service and a lack of qualified providers were leading factors in the decision to end birthing services at the small, independent hospital that delivered 107 babies in 2024.

For maternity care, traveling long distances on country highways requires more planning and more time, two things that can be hard to find during the uncertain hours surrounding a delivery. An hourlong drive or more also creates greater risk to both mother and child if any complications arise.

"Anytime someone has to travel in pre-labor or active labor, it could cause a negative outcome," Williams said. "Obviously the closer you are (to a birthing hospital) the better off you'll be."

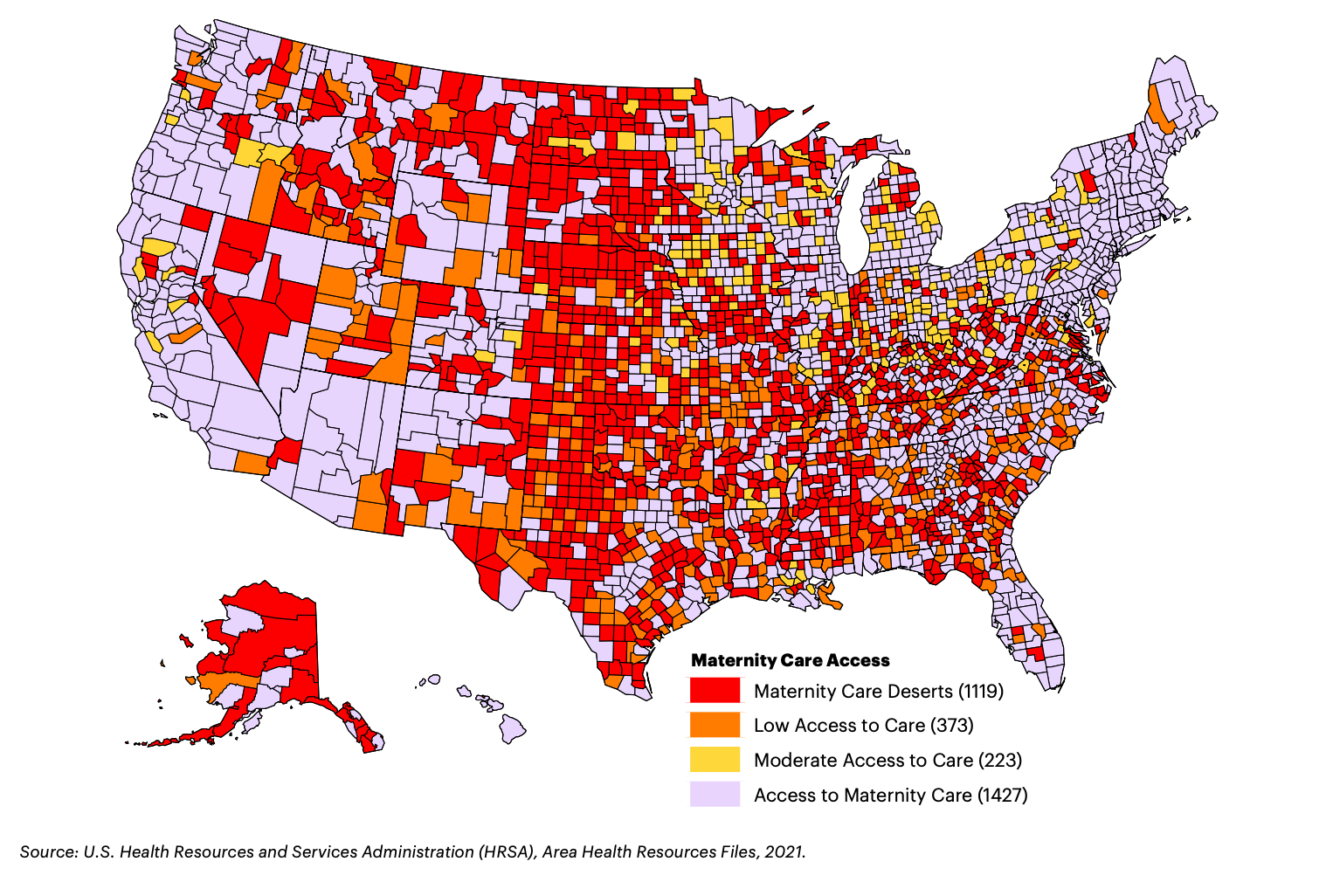

'Maternity deserts' expanding in SD, US

Health experts across the country are increasingly concerned that the reduction in birthing sites, especially in rural areas, will lead to more health complications and even deaths among mothers and children.

"Access to quality maternity care is a critical component of maternal health and positive birth outcomes, especially in light of the high rates of maternal mortality and severe maternal morbidity in the U.S.," according to an exhaustive report by the March of Dimes.

Ending birthing services in Winner, which Williams hopes will be temporary, adds to a growing "maternity desert" in South Dakota. The state ranks second-worst in the nation for percentage of counties without delivery services or obstetric care. North Dakota has the highest number nationally, with 74% of counties without birthing services, and South Dakota has 56% of counties without the service, according to the March of Dimes.

Winner also becomes the latest rural hospital in the U.S. to end delivery services, joining more than 200 others that have ended the service over the past decade, including the hospital in Sisseton, in northeast South Dakota, as reported previously by News Watch.

According to the March of Dimes report, more than 9% of South Dakota women live more than an hour from the nearest birthing hospital, compared to 1% nationally. Furthermore, 16% of new mothers in South Dakota did not receive adequate prenatal care, according to the report.

The shortage of women's health care providers is expected to worsen in coming years.

According to a report from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, the U.S. will face a shortage of about 5,200 obstetrician-gynecologists by 2030 and South Dakota will see a shortage of 30 providers, roughly 25% fewer than what is needed.

Costs, personnel are barriers at rural hospitals

The hospital in Winner faces many of the same challenges as other rural hospitals across the country.

Williams said he has had great difficulty recruiting and retaining doctors in the city of fewer than 3,000 people, especially those who specialize in obstetrics and gynecology or family physicians who are certified to perform deliveries.

The greatest barrier to continue offering delivery services was a lack of qualified personnel, as delivering a baby requires a trained OB-GYN or family doctor and two nurses. That staffing level can be difficult to reach, especially when a birth occurs overnight or on weekends, Williams said.

The costs of delivery are also a major hurdle to providing birthing services, he said. With a high percentage of expectant mothers at Winner Regional Health hospital on Medicaid or other government insurance plans that typically do not cover the full costs, the hospital loses thousands of dollars on almost every birth, Williams said.

On average, it costs $65,000 a day to operate the hospital, and the ongoing nursing and physician shortage forced the hospital to spend about $1.2 million a year on temporary traveling practitioners, many in the OB-GYN field, he said.

The region of South Dakota served by Winner is an especially bad place for a new maternity desert, according to the U.S. Census. The six counties surrounding the hospital all have birth rates above the state average, with Todd County, home to the Rosebud Indian Reservation, among the highest.

South Dakota also has a high rate of maternity complications and challenges compared to other states and the nation. The state infant mortality rate of 7.8% in 2023 was 44% higher than the national average of 5.4%.

According to a recent South Dakota Department of Health report, 7.1% of babies born in 2022 were low birth weight, 2% of mothers had no prenatal care and 30% of mothers were on Medicaid or other government insurance programs, including the Indian Health Service.

About 13% of babies suffered from abnormalities and 10% of infants required care in a neonatal intensive care unit in 2022, the report said. South Dakota only has three NICUs, two in Sioux Falls and one in Rapid City, according to neonatal0gysolutions.com.

Abortion ban a disincentive to practice in SD

South Dakota's abortion law also makes it more difficult to recruit and retain physicians, said Amy Kelley, M.D., an OB-GYN at Sanford Health in Sioux Falls.

The strict abortion ban – which allows for medically necessary abortions only to save the life of a mother – is turning away some delivery doctors, she said. Many worry that ambiguity in the law about exactly what constitutes a threat to the life of a mother could put them at risk of a criminal charge if they conduct an abortion during an emergency, Kelley said.

"We shouldn't have to risk our license or our freedom when conducting a medically necessary procedure," she said.

Kelley, who works on state affairs for the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists and also attends national conferences, said she's heard numerous delivery doctors across the country say they won't practice in states where abortion bans could put them in legal jeopardy.

"It is not hyperbole," she said. "People in this field are repeatedly saying, 'Why would I come there with the laws the way they are?'"

Avery Olson, 30, is a Rapid City native who graduated from medical school at the University of South Dakota. Olson is nearing the end of her medical residency as an OB-GYN in Hawaii.

Olson, who delivered her first baby as a medical student at Winner Regional Health a few years ago, said she hasn’t decided where to practice, and added that her partner’s ongoing job search will also play a role in where they decide to live and work.

Olson really wants to return to her home state but is concerned about the less-than-supportive environment for women’s health and the ambiguity in the current laws surrounding maternity in South Dakota.

“I miss home a lot because I’m a South Dakota girl through and through,” she said. “But it (the current legal and political environment) would make it easier for me to accept that I would go to a different place.”

Worsening climate for women's health care

After more than 30 years of providing women’s health care in western South Dakota, and delivering more than 9,000 babies along the way, OB-GYN Marvin Buehner, M.D., of Rapid City decided to retire in late 2024.

Buehner, 67, had hoped to sell his practice, where he built a reputation for kindness, quality care and a devotion to helping women in underserved populations, including Native Americans.

While the need for birthing and other services remains extremely high, and his practice was highly profitable, Buehner tried to sell his practice but was ultimately forced to close Black Hills Obstetrics and Gynecology for good.

“We had a great reputation and more patients than we could see,” Buehner told News Watch. “But nobody wants to come to South Dakota, and you can’t really blame them.”

Serving as an OG-GYN is a tough job, he said, given the long hours, being on call 24/7 for several days in a row and caring for patients who often lack insurance or are on Medicaid. But things have worsened in recent years due to what Buehner said increasingly feels like a hostile political and cultural environment toward women and women’s health care in the state and country.

“It’s a cultural problem that is trickling down into the mechanics of health care, and women’s health care is not only a low priority, it’s also a target,” he said.

The current law surrounding medically necessary abortions does not jibe with established medical reasons for terminating a pregnancy in a crisis situation, Buehner said, which makes practicing in states with a near-complete ban more stressful and mentally draining.

Buehner is a co-chair of the group Doctors for Freedom, which formed in 2024 to support a statewide ballot measure to legalize first-trimester abortions. The measure failed in November.

“An abortion is a tragedy every time,” he said. “But the reasons a woman or a doctor would choose to end a pregnancy are multifactorial and can’t be easily simplified.”

Buehner said he is pained to leave the medical field at such a devastating time for women’s health. The shortage of OB-GYNs has led to reduced rates of prenatal health care, especially in rural areas and among lower-income populations, including those on reservations, he said.

“That is increasing the maternal mortality rate, which is already abysmal in South Dakota,” he said.

Buehner said he sees little hope that women’s health care will improve anytime soon in South Dakota. And yet, he believes the hard work of individual providers, and a potential grassroots return to greater support for women’s health care, will someday reshape the landscape into a positive future.

“It’s the dark of night right now,” he said. “But at some point, there will be a dawn or a movement and a realization that this isn’t working and that we need to change.”

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they're published. Contact Bart Pfankuch at bart.pfankuch@sdnewswatch.org.