BRIDGEWATER, S.D. – As bird flu ravages poultry farms across the country – including in South Dakota – fears are growing that the highly contagious avian influenza virus could mutate and begin to spread widely among the world's human population.

The virus already has caused devastating effects in the state, which has seen the second-highest number of outbreaks in commercial poultry flocks in the nation.

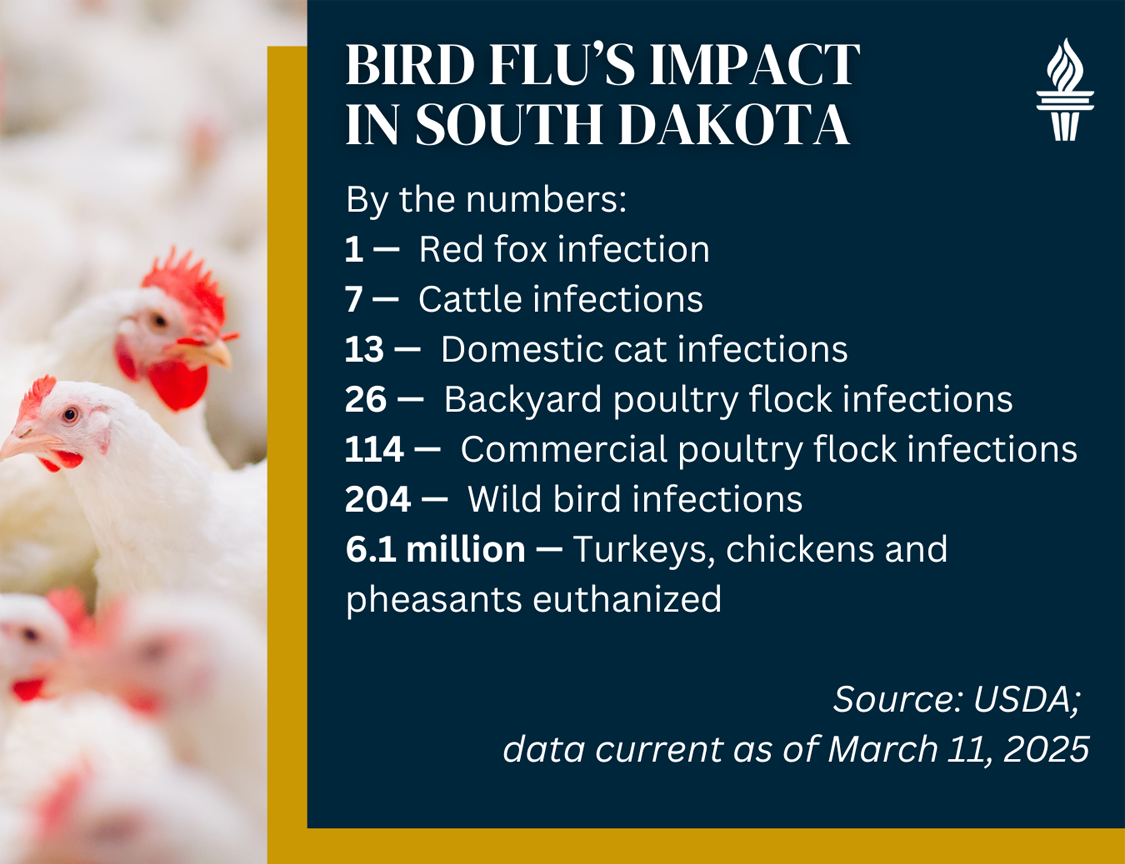

The 114 commercial outbreaks in South Dakota, along with another 26 backyard flock infections, have led to the death or intentional killing of more than 6 million turkeys, chickens and other birds, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture.

Many of the outbreaks in the state, the latest coming in January, have been at turkey farms operated by Hutterite colonies in the eastern half of the state, including at the Oaklane Hutterite Colony near Bridgewater.

But in late 2023, the virus was detected in a flock of farm-raised pheasants in South Dakota, leading to the killing of about 30,000 of the birds that draw hunters from around the world each fall. As in other states, the virus has also spread to mammals in the state, causing the death of a handful of cattle and more than a dozen domestic cats.

So far, no human cases have been reported in South Dakota. Nationally, however, about 70 people have been sickened by the virus, mostly farm workers or veterinarians who were exposed to infected birds or cattle. In January, an elderly resident of Louisiana with underlying medical conditions became the first person to die of bird flu in the U.S. after being exposed to sick birds.

166 million birds destroyed in United States

The current outbreak of Highly Pathogenic Avian Influenza, or H5N1 virus, began in the U.S. in February 2022. Since then, the virus has been detected in all 50 states, causing more than 1,600 individual outbreaks in commercial and backyard poultry flocks and leading to the death or euthanasia of 166 million chickens, turkeys and other birds.

While the most tangible outcome of bird flu for consumers has been the rising cost of eggs and chicken breasts, a different, more ominous concern is rising among scientists and public health officials who closely monitor bird flu and study ways to prevent its spread.

There has been no known human-to-human spread of bird flu so far in the U.S, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. And yet, numerous scientists are becoming concerned that bird flu could become the next pandemic and potentially cause devastating consequences to human populations across the world.

"We're afraid this virus could cause a human pandemic because humans have very little immunity against this particular avian flu virus," Scott Hensley, a leading bird flu researcher at the University of Pennsylvania, said in a January video presentation. "The problem is that flu viruses acquire mutations all the time. And we know that the virus is only one or two mutations away from being able to cause severe disease in humans."

The current risk to humans, especially those outside the agriculture industry, remains "very low," according to the CDC. So far, the bird flu virus has not been found to bind well to human cells or take hold in the human respiratory system.

But the virus has already shown a ready ability to mutate, not unlike how the Influenza A and B and COVID-19 viruses show slight mutations each year. Bird flu can be spread through direct contact, by breathing airborne particles or through shared water sources.

The spread of infection from wild migrating birds to captive poultry flocks, and the subsequent mutations from birds to bovines and now cats is a cause for alarm, said Todd Tetrow, the director of veterinary services at Dakota Provisions, a large turkey processing company in Huron.

"It can jump species, so anytime there’s virus out there, and other species can be exposed, it can sure jump," Tetrow told News Watch. "Anytime it jumps into a new species, there’s more concern and thoughts that this thing is getting to where it’s scary for humans."

Turkey farms hit hard by bird flu

South Dakota has been a hotbed for bird flu infections for two reasons.

The state is along the flyway for many species of migratory birds, which are the known carriers of the virus.

Also, South Dakota is a major producer of turkeys that are mainly raised indoors within concentrated animal feeding operations. The state also has smaller chicken and pheasant breeding operations that can be susceptible to bird flu outbreaks.

The 41 Hutterite turkey producers who make up the farmer-owned Dakota Provisions cooperative have suffered so many bird flu outbreaks in the past three years that the group has purchased its own industrial firefighting foam system. Firefighting foam, which eliminates oxygen when dispensed, is the current preferred method of quickly and efficiently "depopulating" a flock of infected birds.

The Oaklane Hutterite Colony west of Sioux Falls has endured two bird flu outbreaks in the past two years, which in total required the killing of about 21,000 adult turkeys and juvenile birds, said colony director John Wipf.

On both occasions, Wipf said, he noticed that water consumption among his turkeys had fallen, and some birds showed signs of malaise and a few died. Both times, birds were sent to South Dakota State University for confirmation that bird flu was the cause.

When any bird is infected, all birds from that barn must be destroyed, he said. The USDA sends in experts to monitor the killing, which was done by a local firefighting agency.

Watching his flocks be depopulated is heart wrenching, he said.

“The smallest ones really wanted to live and they tried to climb on top of the foam, but it wouldn’t hold them up,” he said.

Dead birds are then composted in a landfill onsite, and the barns must then be sanitized and approved by the USDA before reopening.

The value of the lost birds was likely about $300,000, though the federal government indemnifies farms for bird flu and pays farmers an adjusted amount to cover most losses.

Wipf said he takes precautions to prevent further infection, such as requiring staff to wear boots and other protective clothing` and by keeping things clean and disinfected.

He isn’t sure how his flocks became infected, but he believes migratory birds are the likely culprits.

“It’s a bad luck situation for sure because it’s very difficult to diagnose where it came from and how it got in here," Wipf said. "We have no clue, but I think part of it was bird migration, geese and ducks that fly over and poop on the barn and our materials. Or it could have been brought in by wild birds that get into the barns.”

Pheasant farmers lose major flock

The bird flu outbreak that struck the Gisi Pheasant Farm near Ipswich, 30 miles west of Aberdeen, began with a single bird testing positive in December 2023, according to company general manager Loretta Omland. Ultimately, three positive tests for bird flu were confirmed, she said.

To Omland and her family members that run the farm, the flu cases appeared isolated to one barn at their breeding operation at nearby Craven. No other birds appeared to be sick or dying in those barns or at other locations in Wessington Springs and Miller, Omland said.

Suddenly, the family found itself embroiled in a difficult, emotionally draining effort to save their other breeders and hens. Gisi Farms in 2022 provided about 480,000 ringneck pheasants to a large number of customers that mostly include South Dakota hunting resorts and preserves.

In the days following the positive tests, they ran up against USDA officials who were unwilling to make exceptions to rules stating that entire flocks of birds must be destroyed quickly, even if only one or a few birds test positive for bird flu.

“We told them, ‘We don’t care about indemnification,’ because those were our birds,” Omland told News Watch. “I had to call all these customers and tell them that we can’t get your birds, and that affects the restaurants, the grocery stores, the preserves and all these people in the hospitality and hunting industries.”

The family sought the help of the South Dakota state veterinarian and the state congressional delegation to ask for an exception that would allow them to mitigate the loss of birds.

“The USDA came back and said that if we didn’t kill those birds, we’d be in jeopardy of losing indemnification and that South Dakota could be in violation of international trade laws,” Omland said.

The family relented and agreed to the killing of about 30,000 pheasants, later receiving a roughly $1 million indemnification that did not cover their full losses and cleanup costs, Omland said.

“It was horrible, just horrible because those were all healthy birds,” she said.

Since then, Gisi Farms has enhanced its biosecurity efforts to prevent further outbreaks, Omland said.

“We test and test and test and clean and clean and clean, but you can only get so far in what you do,” she said. “You do everything you can, but at the end of the day, you just say more prayers.”

Research and prevention steps underway

News is breaking almost weekly about the impacts of bird flu and the efforts of the scientific community to slow its spread and to reduce its ability to infect humans.

In mid-March, thousands of geese were found dead in and along Lake Byron in Beadle County and state game officials said they believe bird flu was the cause of the mass die-off.

In January, a new strain of bird flu called H5N9 was determined to be the source of infection of a commercial duck farm in California. While that new strain is not more infectious or dangerous to birds or humans, scientists said it shows how quickly the virus is mutating.

Some experts worry that if separate viruses intermingle – such as a person who has influenza A is then exposed to H5N1 – that a cross-virus mutation could occur and open the door to greater human infections or birth of a virus that can spread among humans.

In December, the USDA launched its National Milk Testing Strategy, which among other things tests milk held in silos for H5N1 prior to distribution to humans. South Dakota is one of 45 states to sign up for silo testing.

In March, the USDA announced it was launching a $100 million research effort into finding vaccines or possible treatments for bird flu infections. The funding is part of a proposed five-pronged, $1 billion federal plan to study, prevent and limit the spread of bird flu in commercial poultry flocks.

Bird flu containment efforts were slowed when USDA employees working on bird flu issues were fired as part of government efficiency efforts, and some bird flu information was not being shared by the CDC due to position and funding cuts. The USDA bird flu workers have since been rehired.

The CDC, USDA and Food and Drug Administration are all working to monitor bird flu outbreaks and spread. The USDA has created an easy-to-navigate website where bird flu data is tracked by state and the CDC has a bird flu information page.

The farm-level response to bird flu in South Dakota has centered around close monitoring of bird health and behavior and through testing of poultry flocks prior to slaughter, Tetrow said.

Some farmers in South Dakota and other states have used cannons or fireworks to scare away migratory birds or have tried to eliminate ponds where migratory birds congregate near their barns.

Tetrow said he hopes the agricultural, governmental and scientific communities can work together to take more steps to evaluate the causes and effects of bird flu and take preventative methods to slow its spread.

"I'd like to see us reevaluate what we're going to see if there are more approaches and tools we can add to our toolbox to fight this," he said.

The USDA in February gave conditional approval to a bird flu vaccine for poultry, made by the firm Zoetis. But to date, the U.S. has not followed the path of other countries such as China, Mexico and some European countries where use of poultry vaccines is widespread.

Tetrow, who spent more than a decade working in the South Dakota state veterinarian's office, said he supports the concept of vaccinating poultry in order to protect both bird and human populations.

"It won't prevent infection, but it decreases mortality and the amount of virus that is shed," he said. "If we can find a vaccine that can do those things, I think we need to figure out how to employ that."

Hensley, the University of Pennsylvania biologist, said a major goal of ongoing research is to develop a human vaccine. "We want to be able to respond if this virus acquires the mutations that are needed to effectively transmit from human to human," he said.

This story was produced by South Dakota News Watch, an independent, nonprofit organization. Read more stories and donate at sdnewswatch.org and sign up for an email to get stories when they're published. Contact Bart Pfankuch at bart.pfankuch@sdnewswatch.org.