Some of the most contentious, emotionally charged debates during the 2024 South Dakota legislative session have been about property rights and whether a private company can use eminent domain to force a carbon dioxide pipeline onto land against the owner's will.

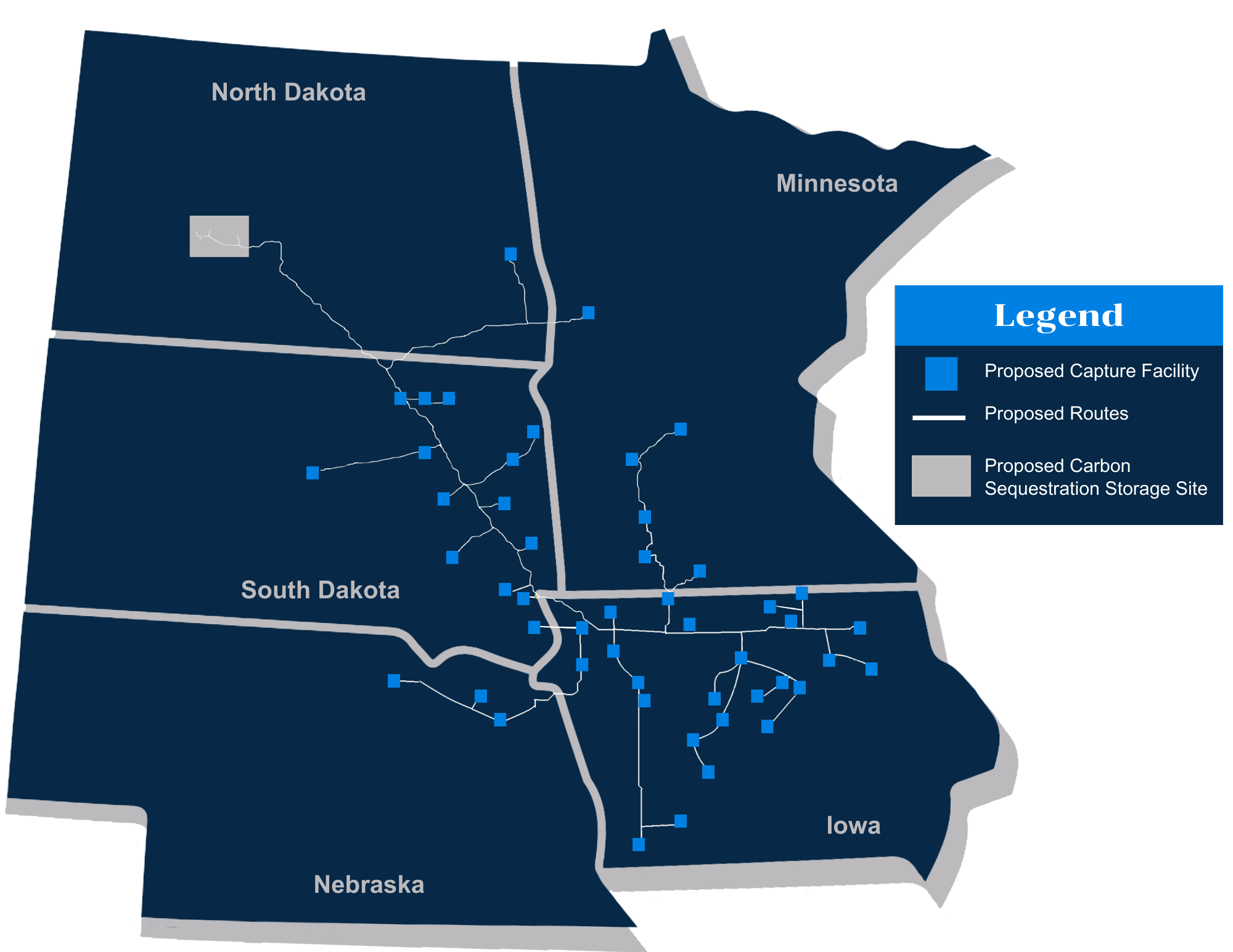

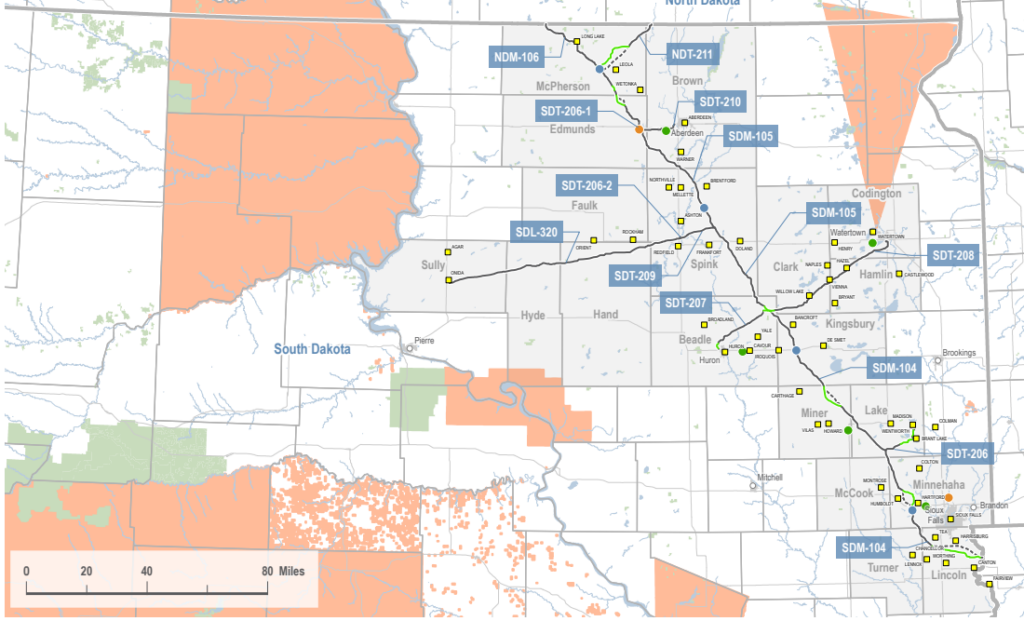

The heated discussions are driven by a proposal from Summit Carbon Solutions to run 470 miles of a 1,900-mile underground pipeline across eastern South Dakota. The pipe would carry liquified carbon dioxide gas from regional ethanol plants to North Dakota, where it would be stored deep underground and kept out of the atmosphere.

In all, lawmakers are weighing 10 bills related to the pipeline and eminent domain, which requires landowners to be paid for the use of their land but gives them little legal recourse to stop it.

"The core of the issue is about taking people’s lands, and it's starting to infringe on the American way," Joy Hohn, whose family farm west of Sioux Falls near Hartford is on the proposed pipeline route, told News Watch.

"Prior to this, our eminent domain laws were for projects that were for the good of the people and that benefit the public. But when you have an out-of-state, foreign-backed company using the threat of eminent domain in their dealings, it's not good and people are really fired up about that."

Kirk Yackley, who farms northeast of Pierre near Onida, said he has heard of landowners being bullied but said he had a good experience with Summit representatives.

Yackley is one of the roughly 3 out of 4 South Dakota landowners along the route who have signed voluntary easements allowing the CO2 pipeline on their land, according to Summit. In his case, the line would cut across about a half-mile of his family's 9,000-acre farm.

“They were very professional and respectful,” he said of Summit representatives.

Summit plans to refile for pipeline permit

The state Public Utilities Commission in September rejected Summit's application after regulators said there were too many conflicts between the proposed route and county guidelines for setbacks between utility projects and existing structures.

Summit officials have said they will refile their permit request once they iron out differences and obtain the voluntary easements needed to site the project. They're also supporting a change in state law to eliminate the ability of counties to regulate pipeline locations.

"We continue to work with landowners and community leaders across the state to find a mutually agreeable path," Sabrina Zenor, a spokeswoman for Summit, wrote in an email to News Watch. "We heard the South Dakota PUC's request to work with counties."

Summit hopes to receive voluntary easements from 100% of property owners along the route, she said. The company has secured them from 75% of South Dakotans, and the documents would apply when the company resubmits an application to the state PUC, Zenor wrote.

Voluntary easement rates in other states include 72% in Nebraska, 75% in Iowa, and 90% in North Dakota and Minnesota, she wrote.

Another company, Navigator CO2 Ventures, dropped its proposal for a pipeline in the region, leaving Summit as the only active project. The companies hope to qualify for billions of dollars in federal tax credits aimed at reducing greenhouse gases.

Some scientists question the efficacy and value of carbon capture and sequestration pipelines, arguing the federal subsidies could be used in more proven, efficient ways to reduce climate change.

But supporters said the pipelines will help the atmosphere and provide foundational support to the U.S. ethanol industry and the corn growers who back it.

South Dakota produces $2.9 billion worth of ethanol annually. Summit's plan would collect CO2 from nearly three dozen ethanol plants, including a handful in the state.

Backers also have said the pipeline is a key component of the proposed $1 billion Gevo plant in northeast South Dakota at Lake Preston that would use corn to make biofuels for the airline industry.

Legislator opinion mixed on eminent domain

At one point during this legislative session, the debate over property rights became so emotional that Rep. Steven Duffy, a Rapid City Republican, said he and another lawmaker had to leave the committee hearing together in order to maintain their safety.

Duffy said the temperature of the debate has fallen since then, but concerns among affected landowners remain high.

One of the leading eminent domain opponents, Rep. Jon Hansen, a Dell Rapids Republican, sponsored House Bill 1219, which would prohibit the use of the process specifically for pipelines that would carry carbon dioxide.

"It’s about protection of our people, the people of South Dakota," he said. "It’s about saving South Dakotans from being the subject of hundreds of lawsuits, condemnation lawsuits, simply for owning land and saying no thank you to a purchase offer."

Eminent domain was intended to allow legal taking of private land while also providing appropriate compensation for government projects that serve a public good and not for private companies that seek to turn a profit, Hansen said.

"This bill is about protecting South Dakota landowners' constitutional private property rights from, frankly, the bullying and harassment we have seen inflicted on our people in this state by an out-of-state, for-profit, foreign-backed company over the last year," he said.

A committee rejected the bill by a 7-6 vote, but it was ultimately moved forward without a formal recommendation. It could still be heard on the floor of the House of Representatives through a procedure known as a "smoke out."

Duffy, a member of the House Commerce & Energy Committee, said he opposed the bill to prohibit use of eminent domain for carbon dioxide pipelines because pipeline companies already have invested upwards of $70 million to get their project sited and approved in South Dakota and four other states.

"Whether you should have eminent domain for private industry, that's a different issue. But I don't think it's fair to say we should change the rules now," Duffy said Feb. 17 at a legislative cracker barrel in Rapid City.

Reform of eminent domain laws might be needed, but it sends a negative message to business and industry if the state changes the laws once a development process has begun, he said.

"It probably does need to be looked at down the road. But I think it's not fair to change it right now in the middle of the game," Duffy said. "That sends a signal to other people that South Dakota may not be business friendly. If they followed the rules, and I assume they did ... it's hard for me to say, 'OK, now you can't (use eminent domain.)'"

State vs. local control also part of the debate

Another highly contentious eminent domain bill, Senate Bill 201, would provide a statewide framework for approval of pipeline projects.

The measure was co-sponsored by Senate Majority Leader Casey Crabtree of Madison and House Majority Leader Will Mortensen of Pierre. The two Republicans have said the measure would streamline the pipeline siting process while also providing protections for landowners and financial help for counties where pipelines are laid.

The bill would bar counties from passing structure setback rules that make pipelines virtually impossible within their boundaries but also provide surcharge payments to counties and require companies to pay for damages to landowners.

In a recent newsletter to constituents, Crabtree called the bill a "comprehensive solution that protects landowner rights and establishes clear infrastructure guardrails."

"South Dakota is open for business, which means we don’t set up roadblocks for projects through regulation, red tape, excessive fees, and indefinite timelines. We provide fairness and certainty in the process for landowners and businesses," Crabtree wrote.

And yet, the measure faces opposition from many landowners who said it would eliminate local control and the ability of individual counties to regulate and possibly ban pipelines within their borders.

A few counties, including Brown, Lincoln and McPherson, have passed or considered measures that would ban pipelines or enforce setback rules that could make the pipelines unfeasible within their borders.

"It's stripping away local control," Hohn said. "It would take away county ordinances that were put in place by a handful of counties that took great care to make sure the intelligent land use and economic development was looked at for their long-range plans."

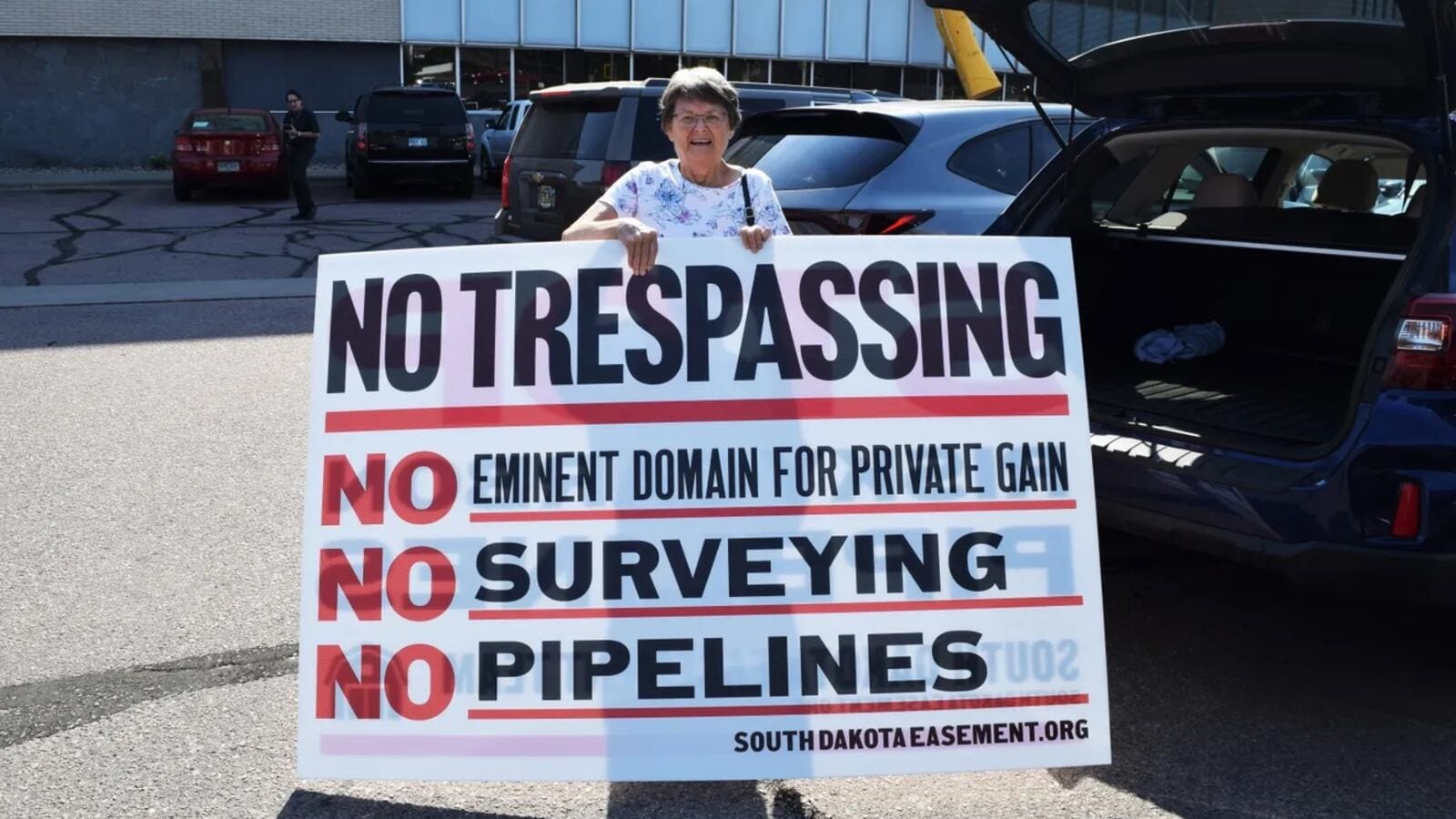

Some landowners unify in opposition

Craig Schaunaman, a former lawmaker whose Brown County farm is on the Summit pipeline route, said he was subject to eminent domain and condemnation proceedings after Summit sought to build the CO2 pipeline across 2.5 miles of his grain farm south of Aberdeen.

Summit representatives did not share his "South Dakota values" and did not deal with him in good faith, he said. As many as 200 South Dakota landowners are or have faced eminent domain proceedings due to their opposition to the pipeline project, Schaunaman said.

"South Dakota has always had an open door for business, but what we haven’t always been is for sale," he said. "It’s our land. And I think if it goes beyond the government taking it, I should be able to say yes or no. Now we seem to have changed that direction and anybody who wants an economic benefit can come in, condemn the land and take it. And philosophically I can't agree with that."

Some landowners opposed to the pipeline said it can make their land difficult to farm and also brings health risks associated with possible leaks of the toxic, liquified CO2.

A number of them have organized.

They regularly drive to hearings in Pierre and have formed a group called Landowners for Eminent Domain Reform. They also created a website to share stories of how they have willingly allowed government use of their land for public projects but believe using eminent domain for business is against South Dakota values. Some have shared that they are enduring sleepless nights as they said they battle to protect their land and livelihoods.

"If you want to stand up for what is rightfully yours, it’s very time consuming and a financial burden," Hohn told News Watch.

According to the Institute for Justice, a nonprofit legal group that monitors eminent domain cases nationwide, the Fifth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution allows for eminent domain only for “public use” and with compensation provided to the property owner. But the institute notes that a 2005 U.S. Supreme Court case, Kelo V. New London, expands eminent domain to allow government and even private entities to use eminent domain for projects that will produce more taxes or new jobs.

The institute gives South Dakota an A grade due to a 2006 state Supreme Court ruling regarding the right of a landowner to prevent hunters from accessing their land that the institute believes weakened the applicability of the Kelo ruling in South Dakota.

The president of one of South Dakota‘s largest agricultural groups, Doug Sombke of the South Dakota Farmers Union, said the public at large should be concerned that under current eminent domain laws, their personal property including land, homes and even cars could be taken without consent by private companies seeking a profit.

"This is not just a farmland issue. This is real for every South Dakotan who owns anything because this can happen to your home, business or any property you own," he said. "Somebody can come in for private gain, a for-profit business, and they could literally come in and wipe our your whole neighborhood and the only alternative you have is to determine what that property was worth."

Farmer had good experience with Summit

Yackley, the Sully County farmer who signed a voluntary easement with Summit, said company representatives who visited with him answered his questions and made some concessions during the easement negotiation process.

He said he isn’t sure of the value and efficacy of the carbon capture process, but he believes the pipeline will help protect the state ethanol industry while boosting the overall state agricultural economy.

Yackley said he received a settlement that would pay him significantly higher than market value for the land where the pipeline would be built.

He testified in 2023 before the Legislature in favor of the Summit project but doesn’t begrudge any landowner of their right to deny Summit access to their land or their ability to say no to the company.

“I have two neighbors who are dead set against the pipeline,” Yackley said. “And I told them to go ahead, that it’s their right to fight it.”

Yackley also said he has heard from people he knows well that Summit representatives did pressure them to allow the pipeline on their land.

“I’ve got friends up north that I trust, and they tell me they were bullied (by Summit). And I believe them because they had no reason to lie to me,” he said. “We just didn’t have that, and I’m sorry that they did.”