New or expectant mothers in South Dakota — and across the United States — are dying during or after childbirth at higher rates than in nearly every other industrialized nation, and evidence suggests as many as 60% of maternal deaths are preventable.

Nine mothers in South Dakota died in 2018 within a year of giving birth, and 10 South Dakota mothers died due to pregnancy complications within six weeks of giving birth from 2010 to 2015, according to federal data.

Experts say that in South Dakota, high rates of obesity, diabetes and smoking, as well as a trend toward giving birth at older ages, may all contribute to the relatively high maternal complication and death rate. A lack of access to health care and inefficiencies or mistakes in the birthing process are also seen as factors. Native American women in South Dakota face a particularly high risk of death during pregnancy.

The state Department of Health has formed a new committee made up of medical professionals that will begin meeting later this year to address the risks during childbirth and seek solutions.

Giving birth is one of the most common reasons younger American women, including South Dakotans, are admitted to a hospital, with roughly 3.7 million births recorded nationally each year (about 12,000 in South Dakota annually.)

Between 2010 and 2015 in South Dakota, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention estimates there were 10 “pregnancy-related” deaths, those that occurred during or within six weeks of a pregnancy ending and are directly due to a pregnancy complication. The number is an estimate based on birth and death records and is likely a conservative figure.

Maternal “pregnancy-associated” deaths — those that occur within a year of the end of a pregnancy but are not necessarily connected to the pregnancy — averaged 7.2 per year between 2010 and 2018, according to the state Department of Health. There were nine such deaths in 2018.

The CDC estimates that roughly 700 American women die due to pregnancy-related complications every year. In 2017, the U.S. maternal mortality rate was 19 deaths per 100,000 live births, according to the World Health Organization. Countries with similar economic conditions saw a much lower rate. The United Kingdom saw 7 deaths per 100,000 live births and Canada recorded 10 maternal deaths per 100,000 births that year.

About 50,000 women in the U.S. annually are estimated to experience life-threatening pregnancy complications such as heavy bleeding, organ failure or the dangerous blood-pressure condition called preeclampsia.

South Dakota does not keep data on the prevalence of severe pregnancy complications, but such problems are “not uncommon,” according to Dr. Kimberlee McKay, who oversees obstetrics and gynecological services at Avera Health. The CDC estimates that severe pregnancy complications are up to 50 times more common than death.

Yet relatively little is known about how often complications arise. In South Dakota, there is no requirement for hospitals to publicly report how often they give new mothers blood transfusions or treat a pregnant woman for dangerously high blood pressure. Until this year, South Dakota didn’t have a statewide review process to study the factors causing pregnant women to die in childbirth.

Many experts believe a lack of systematic review of maternal deaths in each state has been a significant factor in why America has become, statistically, one of the most dangerous industrialized nations in which to give birth.

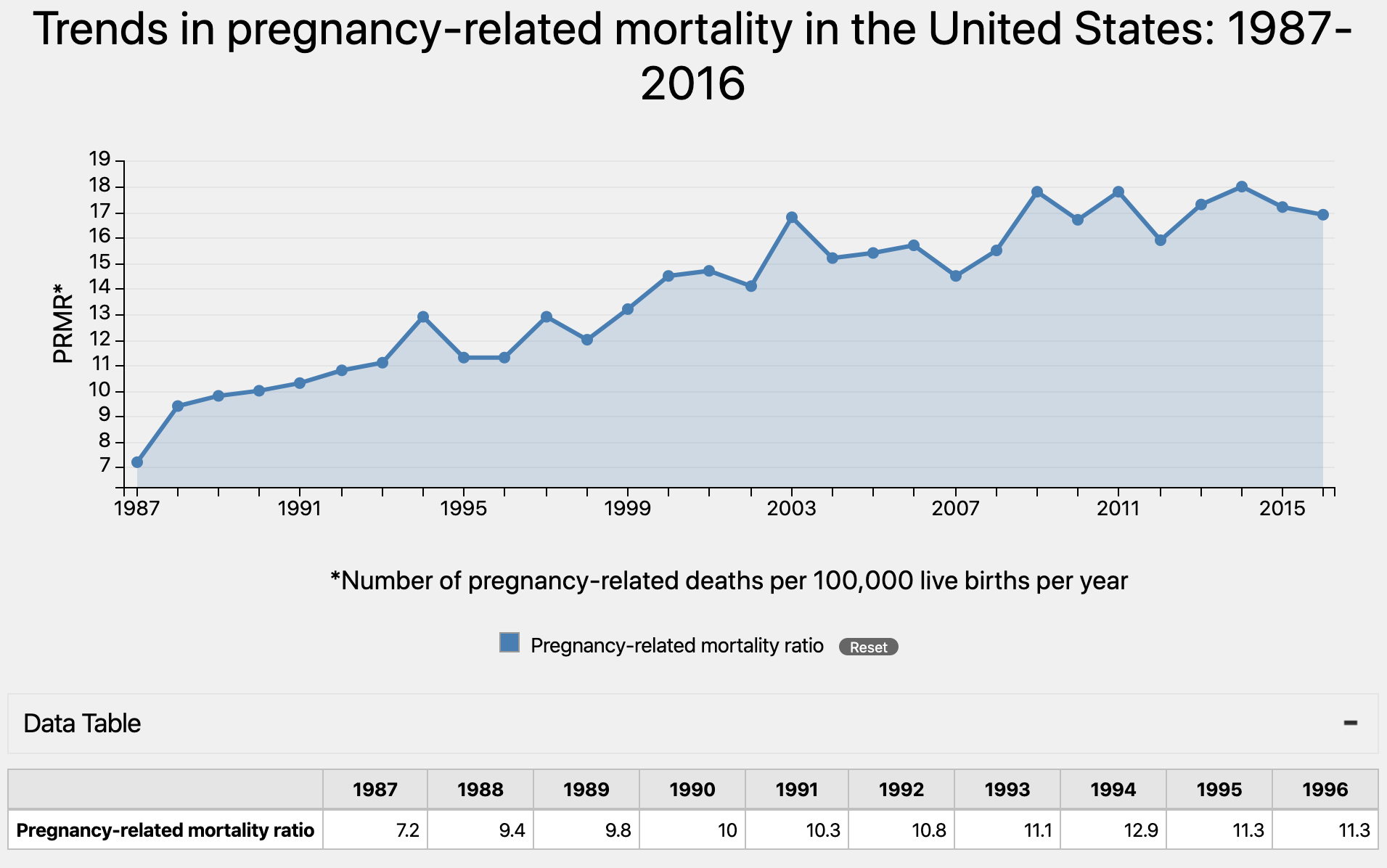

Data that does exist largely are based on national surveys of hospital admissions and discharge paperwork as well as analyses of death certificates and birth certificates. The data show that both maternal deaths and the incidents of life-threatening complications are significant and have been growing in the U.S. since at least 1987.

The occurrence of life-threatening complications, for example, rose by nearly 200% between 1993 and 2014, according to the CDC National Inpatient Sample, a random sample of the nation’s hospital admissions. The data do not show whether the number of South Dakotans who experience severe pregnancy complications has risen.

The national rate of pregnancy-related deaths more than doubled between 1987, when the rate was 7.2 deaths per 100,000 births, and 2014, when the rate was 18 deaths per 100,000 births, according to the CDC Pregnancy Mortality Surveillance System, which surveys death certificates as a way to monitor pregnancy-related deaths.

Existing data also show that roughly 60% of maternal deaths could be prevented. Researchers with the CDC have found that delivery hospitals could do a better job of creating standard procedures for monitoring and responding to emergencies such as high blood pressure and excessive bleeding in mothers before, during and after delivery.

South Dakota hospital systems are aware of the risks. At Avera Health, one of the state’s largest hospital systems, McKay said she and her colleagues have been implementing new protocols for monitoring blood loss. At Sanford Health, another leading health provider in South Dakota, an innovative piece of technology is helping hospital staff better monitor blood pressure in new mothers.

Renewed national focus on maternal health and safety has pushed South Dakota officials to take initial steps toward understanding and addressing the problem. Later this year, the state’s new Maternal Mortality Review Committee will hold its first official meeting to analyze maternal deaths and try to figure out how to prevent more such deaths in the future.

“It may change what we think about maternal mortality,” said Colleen Winter, division director for family and community health at the South Dakota Department of Health.

Causes of high maternal mortality varied

No single cause has been pegged as the reason for America’s rising rates of maternal death and severe pregnancy complications. But the trend has coincided with rising healthcare costs as well as rising rates of chronic conditions such as obesity and diabetes. The average age of women giving birth has risen, too. And, until this year, there really wasn’t a standard for how hospitals were expected to identify, treat and train for responding to severe pregnancy complications.

“What’s interesting about women in South Dakota is that we tend to be overweight and gain too much weight (during pregnancy). We have higher rates of smoking. We are rural, which people don’t think of rurality as being a social determinant of health but in fact it is. And then we have the complications of obesity like diabetes, like hypertension, we have all of those things,” McKay said.

The state has a particular problem with gestational diabetes, a condition that affects how the body processes sugar, McKay said. Roughly one in 10 South Dakotans who got pregnant in 2017 were diagnosed with the condition, according to the South Dakota Pregnancy Risk Assessment Survey. Gestational diabetes, if recognized early, can be treated but it can also cause a baby to grow larger in the womb, McKay said.

“If you have gestational diabetes, the downstream effects of that pregnancy are severe hypertension and big babies, and when you deliver a great big baby, a lot of times your uterus bleeds afterwards,” McKay said.

One of South Dakota’s biggest challenges when it comes to maternal health is proximity to health care. Most of the state is already considered a shortage area for primary healthcare. When it comes to maternal health, McKay described many of the state’s rural areas as maternity deserts, meaning women must travel 30 minutes or more to see an OBGYN or to give birth in a hospital.

Access to quality care may be one of the biggest reasons that Native American women are almost twice as likely to die from pregnancy-related causes as white or Hispanic women, said Dr. Ashley Briggs, an OBGYN at Sanford Health. She has been working with the federal Indian Health Service and other critical access hospitals in the Dakotas to provide better prenatal and post-pregnancy care in rural areas. In 2018, Briggs helped create a multi-state group of healthcare providers and public health officials who seek to improve both maternal and infant health in both states.

“We are trying to do things that focus on the specific concerns of Native Americans,” Briggs said.

Hospitals also share some of the blame for the country’s rising maternal death rate. Experts say that not enough attention has been paid to using standardized research-based best practices to both watch for and treat complications, such as heavy bleeding or high blood pressure in pregnant women before the situation gets out of hand.

The Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health within the Council on Patient Safety in Women’s Healthcare has spent years trying to get hospitals to adopt sets of standardized procedures and practices, called bundles, that can be taught to anyone who works in a birthing hospital.

Many of the bundles are based on practices originally developed in California by the California Maternal Quality Care Collaborative. Implementation of the bundles helped reduce that state’s maternal mortality rate by 55% between 2006 and 2013. California’s maternal death rate during those years fell from 16.9 deaths per 100,000 births to 7.3 per 100,000. California now has one of the lowest maternal mortality rates in the U.S, according to the state’s maternal mortality review committee.

The bundles include such practices as weighing blood absorbing pads in order to more accurately measure blood loss during delivery and making sure every delivery room has easily accessed kits for treating heavy bleeding. Hospitals also develop standard practices for monitoring blood pressure, including how and when to respond if a pregnant woman’s blood pressure gets too high. The new standards also include annual training requirements for hospital staff.

Avera Health has been implementing procedures that conform to the AIM bundles for both high blood pressure and bleeding for a few years now, McKay said. One of the hospital system’s most recently added practices is weighing blood absorbing pads to get a more accurate measure of a mother’s blood loss during and after birth.

“I think our teams have done just a tremendous job of interrupting the bad things that can happen in deliveries because of the approach we’ve taken,” McKay said.

Most hospitals that deliver babies in the U.S. will be forced to have such policies in place by July 1, 2020. The Joint Commission is a nonprofit group that evaluates performance for about 80% of U.S. hospitals, including most hospitals in South Dakota. The group recently updated its accreditation requirements for labor and delivery hospitals to create procedures and training regimes that conform to AIM supported maternal care bundles for monitoring and responding to high blood pressure and bleeding.

Sanford Health also has been developing its own set of practices in response to the Joint Commission’s new requirements to improve patient safety, Briggs said. One innovation the hospital system plans to take advantage of is a way to automatically alert doctors and nurses when a patient’s blood pressure is recorded as dangerously high in their electronic medical record. The technology will help prevent a high blood pressure reading from being missed and going untreated.

“We are all human and we all make mistakes. I think these standards are a way to head that off,” Briggs said.

Having new protocols in place won’t solve all of the problems, McKay said. Medical errors, whether they involve pregnant women or not, tend to be caused by a failure to recognize when a problem occurs or a failure to communicate about the problem, she said. While putting the protocols in place is a good first step, hospitals will need to adopt a more team-based culture to implement them.

“You can put a protocol in place all day long, but unless you address the culture and really adopt a culture of safety, you’re not going to be successful at implementation,” McKay said.

Despite ongoing efforts to prevent maternal deaths at the state’s hospitals, physicians and public health officials say they need to get a better understanding of maternal mortality in South Dakota.

“We don’t have complete data,” said Winter, of the Department of Health.

“They were very interested in improving outcomes for moms and getting a better handle on the data for our state ... any maternal death is too many. Our numbers are smaller, but we’d rather have none.” -- Colleen Winter, division director for family and community health at the South Dakota Department of Health

Sanford Health also has been developing its own set of practices in response to the Joint Commission’s new requirements to improve patient safety, Briggs said. One innovation the hospital system plans to take advantage of are blood pressure cuffs that automatically notify operators when a patient’s blood pressure is dangerously high. The technology will help prevent a high blood pressure reading from being missed and going untreated.

“We are all human and we all make mistakes. I think these standards are a way to head that off,” Briggs said.

Having new protocols in place won’t solve all of the problems, McKay said. Medical errors, whether they involve pregnant women or not, tend to be caused by a failure to recognize when a problem occurs or a failure to communicate about the problem, she said. While putting the protocols in place is a good first step, hospitals will need to adopt a more team-based culture to implement them.

“You can put a protocol in place all day long, but unless you address the culture and really adopt a culture of safety, you’re not going to be successful at implementation,” McKay said.

Despite ongoing efforts to prevent maternal deaths at the state’s hospitals, physicians and public health officials say they need to get a better understanding of maternal mortality in South Dakota.

“We don’t have complete data,” said Winter, of the Department of Health.

Committee formed to improve safety

At the end of 2018, South Dakota was one of only nine states that had not established a Maternal Mortality Review Committee to analyze each death of a pregnant or recently pregnant woman. Establishing a state MMRC is regarded by the CDC and the Association of Maternal and Child Health Programs as a necessary first step toward lowering the rate of maternal deaths.

“They were very interested in improving outcomes for moms and getting a better handle on the data for our state,” Winter said.

After months of laying the groundwork, Winter said South Dakota’s MMRC will hold its first meeting later this year to evaluate all nine maternity-associated deaths reported in 2018. The evaluations will help public health officials and healthcare providers pinpoint which areas of maternal health need more focus. The state has had success with a similar review committee that helped reduce the state’s rate of infant deaths.

“In the case of infant mortality we found that infants were dying as a result of not having safe sleep environments and so we implemented a statewide safe sleep program,” Winter said. “I feel like we’ll learn a lot from maternal mortality review.”

Because the DOH created the new MMRC without any additional funding from taxpayers, its members will be volunteers from the South Dakota medical community, Winter said. The state’s hospitals also will be asked to provide access to medical records for each maternal death recorded in the state.

That access will be provided through a memorandum of understanding between the DOH and each hospital or hospital system. A DOH employee who has been assigned to work on maternal health will collect the pertinent information from each set of medical records and format a report on each death for the committee to review.

The committee may take years to devise policy recommendations. Maternal deaths are rare, of the roughly 11,890 women who gave birth in South Dakota in 2018, only nine died. Such a small number of deaths can make it difficult to draw conclusions, Winter said. But, she said, the MMRC will make a difference.

“Any maternal death is too many,” Winter said. “Our numbers are smaller … but we’d rather have none.”