WEBSTER, S.D. – When President Joe Biden mentioned the term “burn pits” while discussing health benefits for military veterans during his State of the Union address March 1, many Americans heard of the issue for the first time.

Congress is crafting legislation to assist post-9/11 combat veterans exposed to toxic smoke from burn pits that contractors used to dispose of human waste, chemicals, munitions and other hazardous materials in Iraq and Afghanistan.

For Jerry Somsen of Webster, who grew up dreaming of being a soldier, and who helped command a South Dakota Army National Guard battalion during Operation Iraqi Freedom, Biden’s words were merely a reminder that the wounds of war can linger, even when their origin is unclear.

The 54-year-old insurance executive started experiencing tremors in his hands a few years after returning from southern Iraq in 2005. The shaking soon spread to both sides of his body and down his legs. Last year, a doctor diagnosed Somsen with Parkinson’s disease, a progressive nervous system disorder, though Somsen has no family history with the disease.

Sitting at his dining room table on a recent evening with his wife Kari, a lawyer who works in Groton, Somsen’s hands shook noticeably as he recounted the neurological tests and other medical appointments that so far have not led to any disability coverage for his illness from the U.S. Department of Veteran Affairs, which only recognizes certain conditions as linked to burn pit exposure.

“I didn’t have this when I went over there, and I came out knowing something was wrong,” said Somsen, a Castlewood native and South Dakota State graduate who retired after 23 years of National Guard service in 2009. “I guess you could say we signed up for it, but we didn’t sign up to not be protected once we got back.”

Somsen is one of 16 South Dakotans on a confidential registry of veterans self-reporting symptoms of burn pit exposure, ranging in severity from nasal congestion to lung cancer. The registry is maintained by Burn Pits 360, a non-profit advocacy group that has pushed the VA to develop its own data gathering effort after Congress passed legislation in 2013.

Further action in Washington will be determined through negotiations between a Democrat-favored measure in the House of Representatives and a more modest bipartisan measure that passed unanimously in the Senate. Veterans and their families continue to seek clarity on what the government can provide in terms of treatment and financial support.

“Most veterans understand that this needs to be an evidence-based process,” said U.S. Rep. Dusty Johnson, R-South Dakota, said in an interview with News Watch.

Johnson voted against the House bill but supports the Senate effort. “They understand that it takes some time to get the science figured out, but what they don’t like is when political fights or bureaucracy slows down the delivery of the science,” he said.

Back in Webster, as Somsen and his wife look through photographs of his 14 months in Kuwait and Iraq, they lament the frustration of seeing a once-healthy husband and father in the grip of a debilitating disease, with little relief in sight.

“We trust these (veterans) with our lives and with national security,” Kari Somsen said. “But when it comes to him saying, ‘Look I have this issue and I believe it came from Iraq,’ we need to make it so we trust these people a little bit more. They’re not lying. They need help.”

Called to serve in Iraq

Jerry Somsen grew up as one of seven children on a family farm outside Castlewood, S.D., south of Watertown. He joined five of his siblings in attending SDSU, but not before becoming fascinated with the pomp and precision of military service.

“My oldest brother, Lowell, was in the National Guard as an officer,” Somsen recalled. “I went to one of his drills at the armory in Mitchell and decided that I wanted to be that guy.”

Jerry entered the Reserve Officers’ Training Corps at SDSU with basic training already completed, wanting to hit the ground running. By the time he graduated in 1990 with a degree in mathematics, he headed to Field Artillery Officers Basic School at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, where his math background helped him excel.

By the time he earned his master’s degree at SDSU in 1994, Somsen had three children and was going through a divorce while still a member of the National Guard but pondering his path. He took a job at Dakotah Incorporated in Webster in 1997 and met Kari through church, teasing her about her lines in an Easter pageant.

They were married in 2000 and added a daughter to a family that already included three girls. But any semblance of domestic bliss was staggered when Somsen showed up to work on Sept. 11, 2001 and saw the planes hit the World Trade Center.

He was in the South Dakota Army National Guard’s 2nd Battalion, 147th Field Artillery. The 1st Battalion was called to action in 2003 as part of Operation Iraqi Freedom but never deployed overseas from Fort Sill. “They weren’t needed,” said Somsen. “The war got over too fast.”

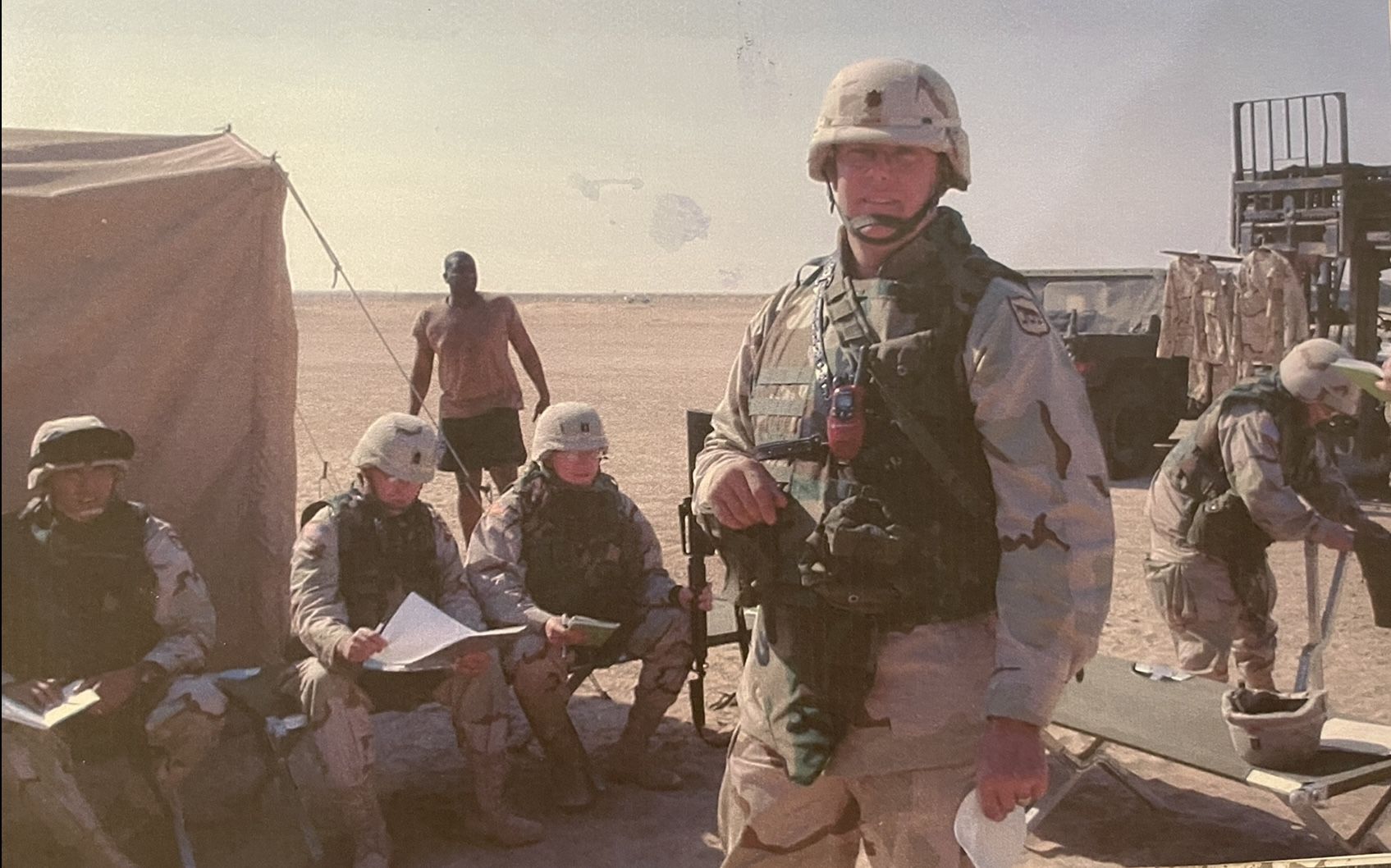

The 2nd Battalion deployed later that year with the mission of capturing and destroying enemy ammunition, with Somsen serving as executive officer, second in command. “We didn’t know what our mission was until we got there,” he said. “We pulled our stuff out of snowbanks in South Dakota and had it in Iraq within 36 days.”

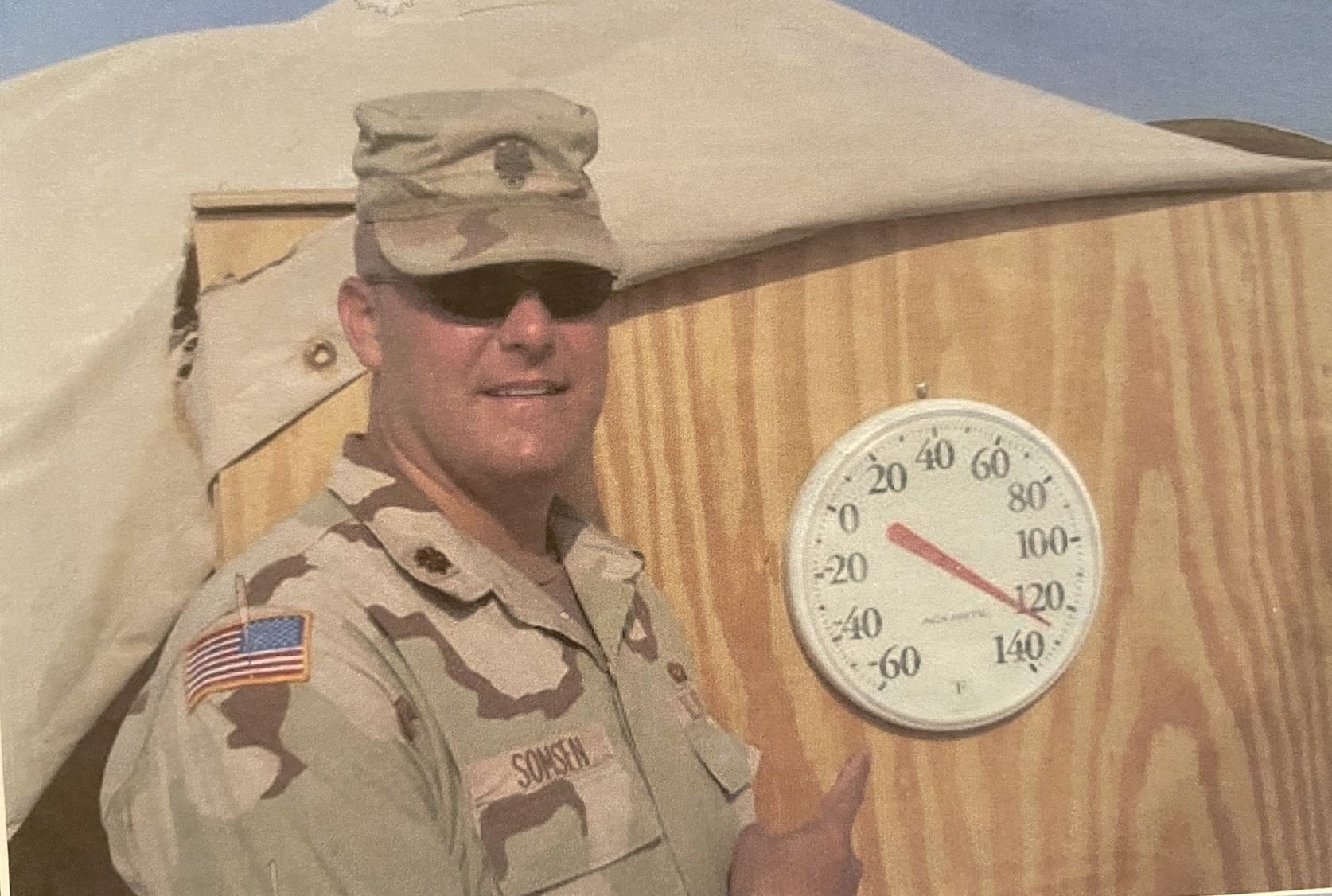

They started in Kuwait and then staged at Camp Cedar in southern Iraq, escorting convoys in 130-degree heat, with Wall Drug bumper stickers on their vehicles. It didn’t take long to notice the thick layers of smoke that wafted through the compound from fire pits on the perimeter.

“From the first day we got there, there was smoke everywhere,” said Somsen. “If the wind was right, you’d walk to lunch in it. We just thought they were burning the trash.”

Soldiers slept in vacated Iraqi ammunition bunkers and were exposed to smoke when rockets and landmines were destroyed through demolition. Somsen spent much of his time at command base but traveled to visit these subordinate units.

Asked if it crossed his mind that the fumes were dangerous, he said, “To this day, I wish it would have. The protection of your soldiers is foremost in your mind, so we were more focused on the enemy threat and IEDs (improvised explosive devices). Looking back on it, every soldier in our battalion probably spent time in those burn pits or in some kind of smoke that wasn’t good for them.”

‘Can I live until I’m 80?’

Even before Somsen returned home from Iraq in February 2005, he felt like something was wrong. He had periods of nervousness or anxiety that didn’t exist before, though he managed to calm himself down.

The tremors in his right hand and side started after his return and worsened, making it difficult to hold the microphone when he gave a Veterans Day speech in Webster in November 2007. When he showed up at his old high school in Castlewood for a Memorial Day event six months later, he had to hide his hands behind the podium and later made the decision that his public speaking days were over.

Somsen, who was awarded the Bronze Star for his post-9/11 service, was aware of the perils of war. He knew that other veterans were more severely impacted by their time in Iraq, and that some had lost their lives. He downplayed what was happening to him, even to his family, and focused on his job in the Webster office of DakotaCare, where he has worked since 2007.

“On the way back from Iraq, I found out I was going to be battalion commander, which is what I’d been working for basically my whole life,” he said. “I still had a chance to make full colonel. If I mentioned anything (about the tremors), I was afraid that I’d be forced into a medical discharge.”

After trying to keep his command while tremors progressed to both sides of his body and down his legs, Somsen made the decision to retire in 2009 with the rank of lieutenant colonel. His next battlefield occurred back home and took the form of hospital corridors and exam rooms after applying for disability, joining a legion of fellow soldiers seeking relief from the government.

According to VA press secretary Terrence Hayes, the department is tracking claims for about 2.5 million veterans who were deployed to the Gulf War region from September 2001 to the present and were potentially exposed to various airborne hazards. Of those, about 1.6 million have filed a claim for disability compensation.

Diagnostic procedures, including a spinal tap and brain testing, led a neurologist to conclude in 2021 that Somsen had Parkinson’s disease. His assessment said the illness was “more likely than not related to his exposure during his time in Iraq, possible bringing symptoms out much earlier than would have otherwise presented. He has no other family risk factors.”

Contacted by South Dakota News Watch, Hayes said the VA’s position is that “no link has been established to date between these exposures and Parkinson’s Disease,” citing research from the National Academy of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine.

Somsen, after years of trying to hide his ailment, is now in the uncomfortable position of having to prove it exists, with Kari as his main advocate. After seeing the most recent review of his disability claim rejected, they’re considering taking their case to the Board of Veterans’ Appeals in Washington D.C.

In the meantime, Somsen shows up at work each day, stays active in the Webster community and keeps up with his daughters, the youngest of whom continued the family tradition by attending SDSU.

“It’s frustrating because I don’t know what the future holds,” he said. “Can I live until I’m 80? What if it’s not Parkinson’s and it’s something else? You realize that it could be more and more debilitating and you look around for answers, and they’re not easy to find.”

Congress explores funding options

In the summer of 2018, U.S. Sen. Mike Rounds, R-South Dakota, met with representatives of the Iraq and Afghanistan Veterans of America to discuss potential legislative efforts to deliver support for injuries from burn pits and other toxic exposure.

Rounds, familiar with the issue as a member of the Senate Veterans’ Affairs Committee, pushed for more research into health effects from burn pits and co-sponsored a successful 2021 bill that improved the level of care veterans exposed to toxic substances received during the pandemic.

The momentum continued earlier this year, when the Senate unanimously passed the Health Care for Burn Pit Veterans Act, which would expand health care eligibility for post-9/11 combat veterans from five years after their discharge to 10 years while also providing a one-year application window for those who missed the initial deadline. The bill would also mandate education and training for VA personnel on toxic exposures and expand federal research in the field.

“This legislation is a small step in the right direction to help make certain that veterans who were exposed to burn pits and other toxic substances get the access to care they deserve,” Rounds said in a statement. He described the $1 billion measure as the first step in a three-part plan.

The House bill, a sweeping proposal to expand treatment and benefits to all veterans with illnesses from service-related toxic exposures and expedite the VA claims process, passed by a vote of 256-174 two days after Biden’s State of the Union remarks.

The House bill, a sweeping proposal to expand treatment and benefits to all veterans with illnesses from service-related toxic exposures and expedite the VA claims process, passed by a vote of 256-174 two days after Biden’s State of the Union remarks. Johnson joined most Republicans in voting against the bill, decrying a price tag of about $300 billion over 10 years and accusing Democrats of political posturing with a bill that can’t pass the Senate and thus won’t become law.

“Sometimes political games get in the way of quick, important bipartisan victories,” Johnson said. “We could have passed the Senate bill out of the House with 400 votes, and we’d already be in the process of delivering this relief. It’s not a silver bullet, but it would move us in the right direction and veterans would be getting the help they need.”

Biden compared the situation to the aftermath of the Vietnam War, when more than 2 million veterans were potentially exposed to Agent Orange, a blend of herbicides the U.S. military sprayed over jungles to remove dense tropical foliage that provided enemy cover. The president said it took far too long to reach decisions on presumptive conditions for those affected, and is determined to now make the same mistake again.

With the president’s urging and legislative efforts under way, the expectation is that compromise between Senate and House bills is likely, providing more clarity on the disability status of post-9/11 veterans.

Somsen doesn’t expect Congress to forge the solution to his situation because of questions about his condition. He hopes further medical research can find a link between what’s happening to his body and the toxic exposures that occurred while he served his country.

At the very least, he is thankful that more attention is being paid to burn pits and soldiers who were potentially affected so they are not left to suffer in silence.

“Hopefully this will help a lot of people like me, who went over there healthy and are feeling pretty ragged right now,” he said.