Editor’s note: This article is the final piece of a three-part special report by South Dakota News Watch. The “Small Towns, Big Challenges” series was supported in part by a grant from the COVID-19 Local News Relief Fund Grant Program sponsored by Facebook.

Lemmon has a new ‘fire in its belly’

When Dave Johnson moved from Chicago to Lemmon to work as an economic-development official nearly a decade ago, his first conversations with locals had a decidedly depressing tone.

Lemmon, like many small towns in South Dakota, had seen its population steadily decline and watched its economy slowly falter. Lemmon’s population fell by 25% from 1990 to 2010, from 1,627 to 1,225; some housing was aging and in disrepair; and retail stores and restaurants had fled its worn downtown district.

“When I first came here, people would talk to me about all the doom and gloom,” Johnson recalled. “I would sit there and look at them and say, ‘You know what, you’re right, we’ve got a lot of work to do.’”

Since then, Johnson — director of the Lemmon Area Charitable & Economic Development agency — said he had seen a spirit of optimism grow in Lemmon as successes in revitalizing the Perkins County town have multiplied.

Johnson said a joint effort by individuals, government and the business community have led to a new vitality and forward-looking mindset in the town of just shy of 1,200 people in the far northwest corner of South Dakota.

“I told them, ‘Well then, let’s take our energy and see what we can do about growing the town,’ and it worked almost every time,” he said.

In recent years, Lemmon has been on a roll. The town landed a new $4 million, full-service IGA grocery store about three years ago; it is now watching the development of a second dollar store; and Lemmon recently approved a $10 million bond issue that will finance a new school set to open for sixth through 12th grades in fall 2021.

And in a rebirth no one saw coming, the town that sits amid wide-open prairies far from any population centers is increasingly positioning itself as a popular stop for tourists and art-lovers who seek a mix of small-town quaintness spiked by the creative juices of local artists.

The most prominent of those artists is John Lopez, a native son whose massive sculptures made of metal scraps and remnants of machinery have become world-renowned for their size, intricacy and captivating creative statements. Lopez has artworks positioned throughout the town, including inside and outside the Grand River Museum, which holds his popular sculpture of pioneer Hugh Glass fending off a bear in a death-defying moment that took place south of town.

Lopez grew up in Lemmon, left for a time to go to college and created presidential sculptures for downtown Rapid City before returning a decade ago to live with his ailing father, who died last winter.

Since returning, Lopez has renovated an ailing historic downtown bar and turned it into the Kokomo Inn Gallery, where he displays his works and spends time with curious patrons.

The results of his efforts have been twofold: His art has drawn tourists and other aspiring artists to town, and his renovation of the Kokomo has provided a blueprint for how other downtown properties can be redeveloped.

“Lemmon took a pretty big hit in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and a lot of our main-street businesses closed,” said Lopez, 48. “Now, there’s been a kind of a domino effect. People have been inspired by watching me renovate this old building and seeing beauty where there wasn’t, so it’s become more attractive to businesses, and now Lemmon has some fire in its belly.”

Lopez is also credited by some with sparking a creative outburst in Lemmon. A group called the Placemakers Co-Op formed and hosts regular meetings where artists or aspiring artists share ideas and generate mutual creativity.

“I think it’s attractive to other artists because artists like to be surrounded by other artist types and it sparks their creativity,” Lopez said. “If you love the prairie and the plains and the beauty of that, you can really be inspired.”

Lemmon also draws tourists to its quirky “World’s Largest Petrified Wood Park” and museum downtown and attracts anglers who seek walleyes in the massive Shadehill Reservoir 12 miles south of town.

Since returning, Lopez has renovated an ailing historic downtown bar and turned it into the Kokomo Inn Gallery, where he displays his works and spends time with curious patrons.

The results of his efforts have been twofold: His art has drawn tourists and other aspiring artists to town, and his renovation of the Kokomo has provided a blueprint for how other downtown properties can be redeveloped.

“Lemmon took a pretty big hit in the ‘80s and ‘90s, and a lot of our main-street businesses closed,” said Lopez, 48. “Now, there’s been a kind of a domino effect. People have been inspired by watching me renovate this old building and seeing beauty where there wasn’t, so it’s become more attractive to businesses, and now Lemmon has some fire in its belly.”

Lopez is also credited by some with sparking a creative outburst in Lemmon. A group called the Placemakers Co-Op formed and hosts regular meetings where artists or aspiring artists share ideas and generate mutual creativity.

“I think it’s attractive to other artists because artists like to be surrounded by other artist types and it sparks their creativity,” Lopez said. “If you love the prairie and the plains and the beauty of that, you can really be inspired.”

Lemmon also draws tourists to its quirky “World’s Largest Petrified Wood Park” and museum downtown and attracts anglers who seek walleyes in the massive Shadehill Reservoir 12 miles south of town.

Cathy Evans, 59, has also played a big role in the revitalization of the town over the past two decades as director of the Lemmon Housing Authority. Evans, who also now serves on the City Council, has led efforts to buy and renovate seven homes over the past 15 years, to tear down 11 blighted homes over the past two years, and she has managed more than 40 public housing units for income-qualifying residents.

Evans said Lemmon, like many other small towns in South Dakota, has a great need for housing to provide safe and affordable living options for elderly residents who can’t take care of their homes any longer, and to accommodate the arrival of new residents or the return of young college graduates who are highly prized in towns seeking to grow or remain vital.

“We’re very progressive about housing here in Lemmon,” she said. “We want to get housing fixed up and ready for people because there’s a great need for housing here.”

Evans said the pandemic could attract more young people to town, including those seeking a slower pace of life in a safe town with a good school district, or among professionals who have increasing options to work remotely. Her daughter, a scientist at the Mayo Clinic in Minnesota, has been working remotely from Lemmon in recent weeks and is hoping to purchase a local property in the event of a more permanent return home.

“I don’t think we’re going to increase our population by leaps and bounds, but I do see the young people coming back,” Evans said. “I really think we’re moving forward here.”

Wheeler said Lemmon is home to a strong religious community of varied denominations that helps provide a sense of togetherness. “That’s a huge plus for the community,” he said.

A sense of promoting a common good became evident when plans for the new school were being considered, Wheeler recalled. The initial plan was to build the school on a site that would require the expensive relocation of a storm-sewer system, which Wheeler and others opposed.

After some negotiation, a compromise was reached and the school construction is now on track at a lower cost, he said.

“It was just the difference between people drawing the line in the sand, or being able to work together,” Wheeler said. “We ended up with just a wonderful plan, because Lemmon has that spirit.”

— Story by News Watch reporter Bart Pfankuch

Webster discovers inner strength

Launching a new business during a pandemic and the economic crisis it caused wasn’t exactly on Mindy Charlson’s wish list.

But the 34-year-old Webster restaurateur had planned for April 2020 as the time frame to open her new venture, Fresh Thymes, to make and sell take-and-bake meals to order using fresh, locally produced ingredients. Then the coronavirus began spreading across the planet, including in South Dakota, causing an unprecedented economic crisis that upended even the best laid plans of small-town entrepreneurs.

In Charlson’s case, the sudden closure of “non-essential” South Dakota state government functions, such as the Department of Health food service inspection program, meant that her kitchen couldn’t get a legally required health inspection, and Charlson couldn’t open Fresh Thymes without it. She was stuck, out of work and with a lease on a commercial kitchen and a husband suffering from a series of medical issues.

“That was probably the toughest thing,” Charlson said.

The town of Webster sits on the western edge of South Dakota’s portion of the prairie pothole region, one of the most important ecosystems in North America. Over the past 20 years, it has developed as a regional hot spot for fishing in addition to its long-term status as a pheasant and duck hunting destination.

Like many of South Dakota’s small towns, Webster (birthplace of news media icon Tom Brokaw) has seen its population slowly shrink as farms and ranches have consolidated. Between 1980 and 2018, the town’s population declined from 2,417 to 1,762, a loss of around 27%.

But in the mid-1990s, the town established an industrial park and began working to attract manufacturers to the community in an effort to lessen its dependence on agriculture. The industrial park successfully recruited three manufacturers to the area but plateaued because Webster didn’t have enough workers trained in skilled trades such as welding, said Melissa Waldner, executive director of the Webster Area Development Corporation.

To address the workforce shortage, business owners, city leaders and the Webster School District worked together to reinvigorate Webster High School’s Career and Technical Education program, Waldner said. Now the program includes hands-on internships — some of which are paid — as well as in-depth training in the types of skills Webster’s manufacturers need.

“It’s just about how we are providing opportunities for our young people to get exposed to those careers,” Waldner said. “Sometimes they just don’t know that they can be really great at that and they might not know that they really like it. They also don’t know that it pays really well.”

The last decade or so has also seen some revival in Webster’s retail landscape, Waldner said. A bevy of boutiques, catering mostly to women, have popped up in the town’s downtown area and have begun to attract shoppers from Aberdeen and Watertown. A couple new shops were set to open in the late spring of 2020 but have delayed opening their doors due to the pandemic.

“We’ve already seen some really good successes, and we feel like we were in a pretty good position when this pandemic showed up,” Waldner said.

Webster also has access to local medical care. The town is home to a Sanford Health medical center with an emergency room. The 25-bed critical access hospital also has a general surgeon and provides pediatric care.

Other business owners were hit by local government action. In Webster, like in many South Dakota small towns, the city council passed an ordinance forcing non-essential businesses, bars and restaurant dining rooms to close on March 25, said Mayor Mike Grosek.

“Everybody handled that super,” he said. “We had cooperation from the bar owners and restaurant owners and a number of individuals that backed the decision that we made.”

The closures were in effect for seven weeks and contributed to a 7.2% decline in city sales tax revenue for the first four months of 2020 compared to 2019, according to the state Department of Revenue.

Times were tough for Jay Pereboom, owner of Pereboom’s Cafe and Boomer’s Outback motel and lodge, when Webster’s ordinance went into effect. Restaurant traffic and tourism had been down for a couple of weeks already as locals and tourists avoided restaurants and travel amid fears of spreading COVID-19.

But part of what has made small towns important pieces of South Dakota’s social, political and economic fabric is the willingness of their residents to step up and support their neighbors when needed. In Webster, the community rallied around its business owners.

“That’s one of the wonderful things about a small town,” said local banker Ellen Hesla. “When something like this happens, everyone takes it pretty seriously. Most of the people in town know each other and so you find a lot of caring individuals reaching out, helping those that need help.”

In one example of community solidarity, the Webster Economic Development Corporation organized a gift card drive from May 7-15. During the drive, every $25 gift card sold was matched dollar for dollar thanks to donors and Webster city government.

“We had six lines and the phones were so busy, folks were getting a busy signal,” said Melissa Waldner, executive director of the Webster Area Economic Development Corporation. “It was just really crazy to see this nice stack of orders that came in to support small businesses during that time.”

Many Webster residents made a conscious effort to get takeout from local restaurants while dining rooms were shuttered, Pereboom said. Still, keeping the cafe’s doors open and its bills paid wasn’t easy.

“We were only open for five hours a day over dinner hours and so even when we had a good turnout, business was still 30% to 40% down,” Pereboom said.

He was one of the 11,000 South Dakota small business owners who received a combined total of $1.37 billion in federally backed Paycheck Protection Program loans, according to the Small Business Administration. The loans were aimed at keeping employees on the job through July.

Webster started reopening on May 1, Grosek said, when restaurant dining rooms were allowed to open at 50% capacity. On June 1, all restrictions were lifted but social distancing guidelines suggested by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention remain in place. By mid-June, Pereboom said business at his cafe was as close to normal as possible given the ongoing pandemic.

“We’ve got about all we can handle right now and we just want to try to take care of customers and train our young employees,” Pereboom said. “Webster is a good town and we just try to take good care of people and take care of what we’ve got.

Charlson’s Fresh Thymes, meanwhile, was finally able to open in May after state health inspectors performed a virtual inspection using the internet. Every day, Charlson creates a new menu based on what ingredients she was able to source from her local suppliers. Prices range from $8 for a single meal to up to $25 for a family meal that can feed six. Demand has been strong, Charlson said.

“Things have been going well,” she said. “I had a good client base from before so people know me, know my approach and what I’m capable of. And then just the option of being able to come in and grab something instead of being out in public has helped.”

As it turns out, using local suppliers has been a boon to Charlson’s business. The pandemic has disrupted national food supply chains to the point that once-common items such as ground beef or milk have become hard to order and more expensive. Finding everything from vegetables to eggs locally has been pretty easy and inexpensive.

“It’s actually easier for me to get local stuff than it is off the food truck,” Charlson said. “I get lettuce from a farm over by Pierpont, and Melissa (Hesla) has a little farm and that’s where I get some of my produce and I get some of my parents’ farm, too. I kind of knew of my suppliers already. That’s one of the benefits of living in a small town.”

So far, Webster hasn’t permanently lost any businesses due to the pandemic, Grosek said. And the fact that both Pereboom’s and Charlson’s businesses have been able to survive and even thrive is an encouraging sign for Webster’s future.

“I think it’s been proven over time, in Webster anyway, that when unfortunate things happen, whether it be to a family or to the city in general because of a storm or that our electricity is out for a week, people band together,” Grosek said. “Everybody does their best to get through. I think we see that once again here. Everybody understands that there are issues out there, health wise, that are very troubling and can be very traumatic and they are doing everything they can do to hold it together.”

— Story by News Watch reporter Nick Lowrey

Edgemont seeks new path to prosperity

South Dakota is home to a handful of true boom-and-bust towns — with gold mining and the railroad industry the cause of many ups and downs — but perhaps no town has been on more of a historical economic roller coaster than Edgemont at the far southern tip of the Black Hills.

“The town has seen many periods of boom and bust,” reads a welcome message on the town’s website. The introduction goes on to describe Edgemont in the early 1900s as a railroad spur connecting commerce to the growing Black Hills region, its stint as a wool-manufacturing hub, its role as an ammunition depot that employed 5,000 people during World War II, and finally its 20-year run from the 1950s to the 1970s as one of the world’s largest producers of mined uranium that fueled the nuclear-arms race.

The town’s population and local economy have fluctuated wildly as a result. Now home to 688 people, the town has seen its population fall by 24% since 1990 and by 61% since its peak of 1,772 in 1960, according to the U.S. Census. Once thriving with retail and basic services, Edgemont went two years without a grocery store in the 2000s and now has no medical care other than ambulance service and does not have a local dentist office.

Some of those fits and starts of commerce left scars on the Edgemont area, including a deep pit of radioactive uranium tailings buried south of town and abandoned mines throughout the region – and occasionally negative portrayals in the media about topics such as a series of doomsday bunkers being offered for sale outside town.

And yet, Edgemont today is known far more for its positive attributes that have attracted and held longtime residents and that have mostly stabilized its population and local economy.

Residents who’ve lived there a while are outwardly proud of Edgemont’s successful school, the relaxed lifestyle and slow pace of living, and its sense of safety that enables children to spend summer days alone outside riding bikes or fishing for bluegills.

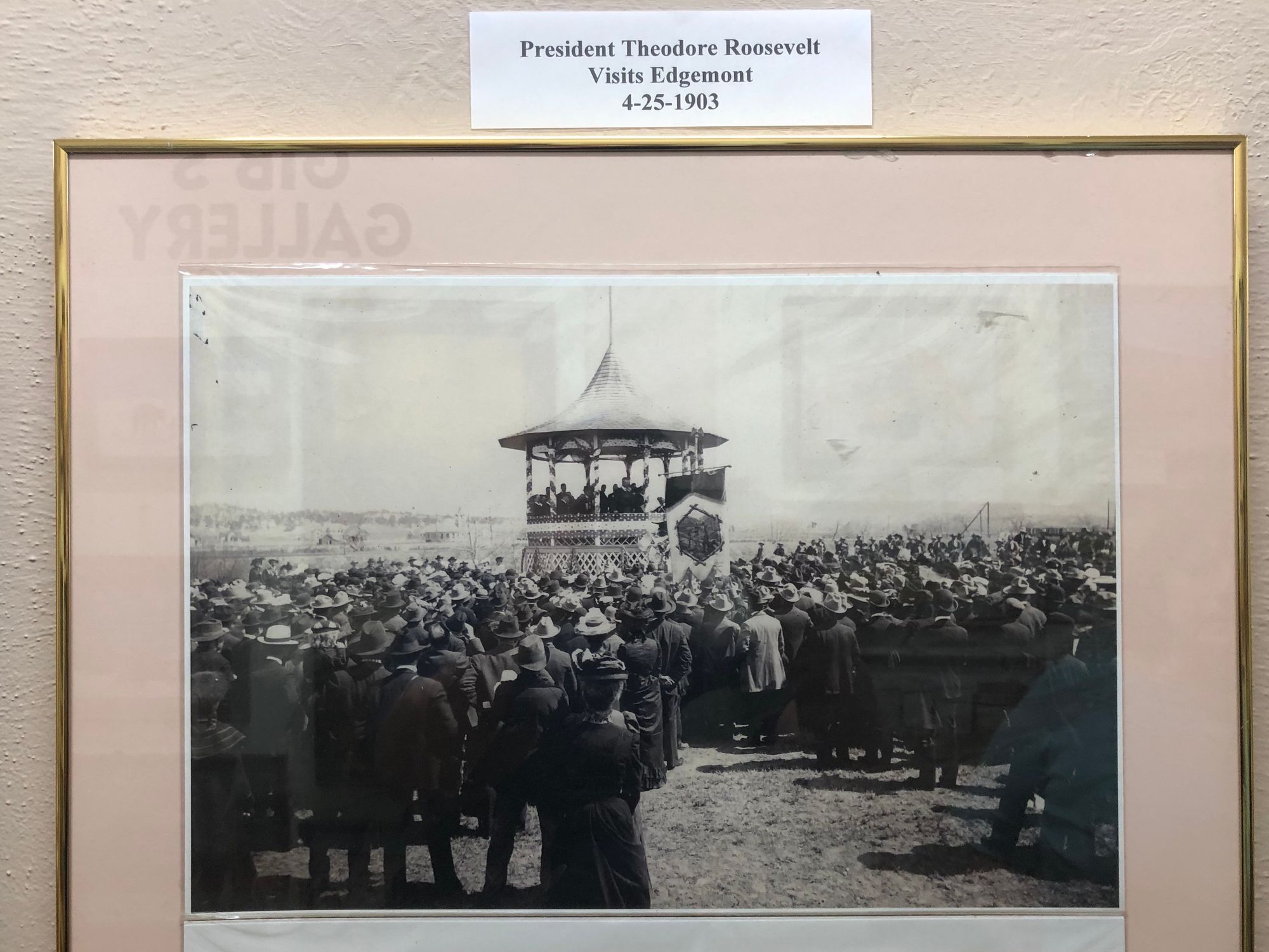

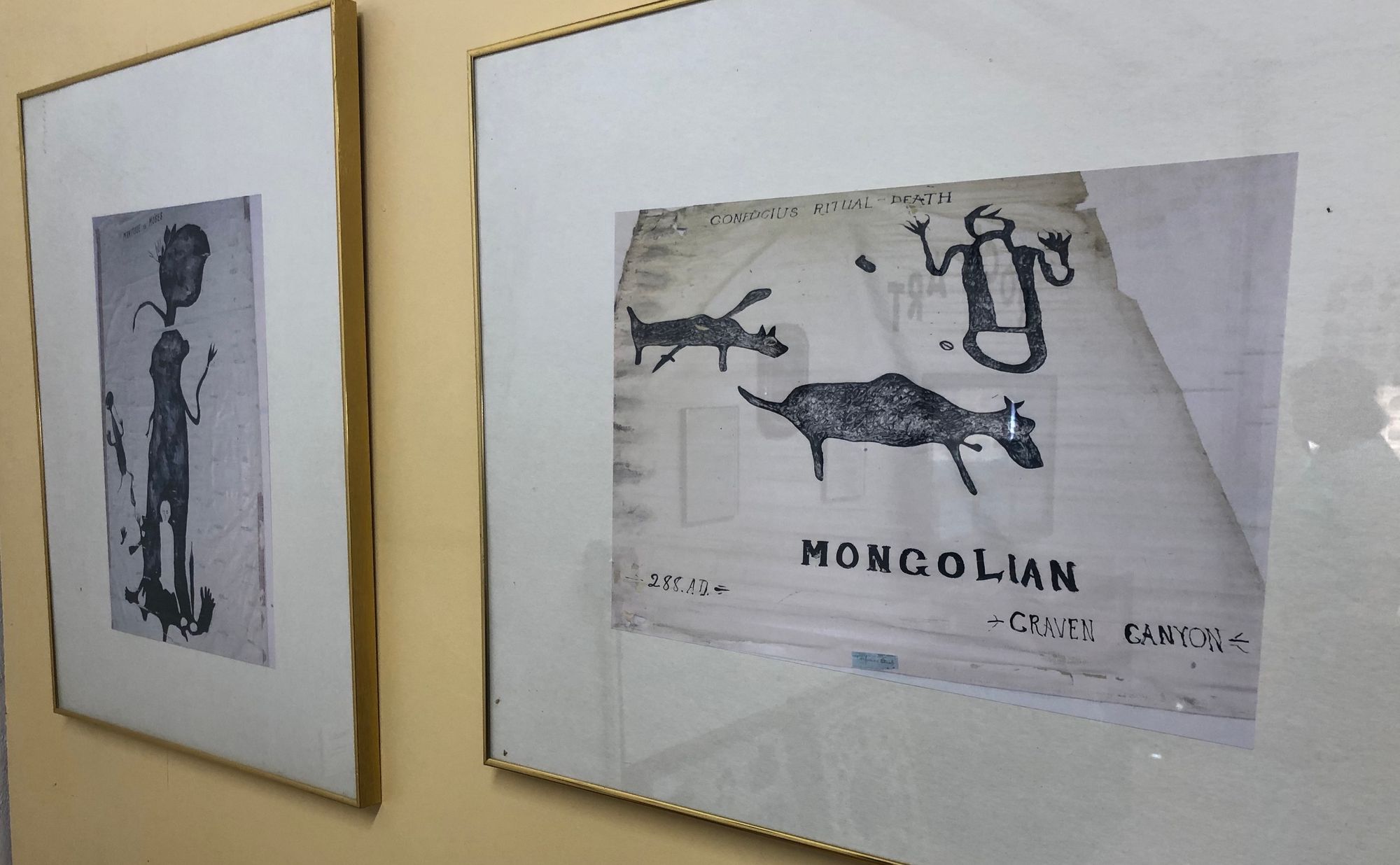

They get excited in describing the town’s recently replaced covered bridge over a pond in a downtown park, the bright white band shell where President Teddy Roosevelt spoke in 1903, its position as the southern terminus of the 109-mile Mickelson Trail biking-and-hiking system, its new high school track and football field built mostly by volunteers, and its staple ranching and railroad industries.

Mary Hollenbeck is one of the grand dames of the Edgemont community and said she has a deep appreciation for the happy life it has provided her and her extended family.

Hollenbeck, 80, grew up in Mobridge but moved with her husband to a ranch northwest of town where they lived and worked for 50 years, raising seven children that have given her 23 grandchildren and nine great-grandchildren.

“It was just the best of both worlds,” Hollenbeck said of the ranch in the hamlet of Dewey. “You could look into Wyoming to the west and see as far as you could see, and look into the Black Hills to the east and see all the trees.”

When her husband died several years ago, Hollenbeck moved into town and remains an active community member, serving in roles that include president of the Edgemont Area Historical Society and working summers at the Trails, Trains & Pioneers Museum in town.

Hollenbeck remains an unabashed booster of Edgemont and its high quality of life.

She acknowledges that as the population has fallen and the economy has stalled, some services have disappeared over the years, including medical and dental providers. The town has only a few restaurants and retail options and no full-service grocery store (the Yes Way convenience/grocery store offers a wide range of meats, produce and other staples, however.)

The town does boast a bustling farm-and-ranch/hardware store, a grain elevator, a feed store, a gun shop, an antiques store, a fabric shop, a thriving community theatre, a busy senior center and a municipal swimming pool. Edgemont is also home to the Fall River County Fairgrounds.

Trips to Hot Springs, 24 miles east, and even to Rapid City, 80 miles north, are not uncommon for residents of Edgemont who need specific products, want to stock up or require dental or health care.

“So many people want endless services and people who live in smaller towns are satisfied with less services and more freedom,” Hollenbeck said. “And during this pandemic, I think our little town has been so much more peaceful than some that are constantly in turmoil worrying about where they go and what they do and who they see.”

Hollenbeck is acutely aware of the declining population in Edgemont and the difficulty it and other South Dakota small towns have in retaining or attracting young people and families.

The problem is rooted, she said, in a lack of new industry and the jobs that would follow. The remote location, the lack of critical health services and the downturn in the agricultural economy and continued automation of the rail industry have also hurt, she said.

The town and region around it have had some close calls in terms of luring news businesses, such as a long-rumored aquaculture plant and the proposed Powertech in-situ uranium-mining operation that has been mired in permitting battles for a decade (Hollenbeck’s son, Mark, is the local leader of that project.)

“We’ve done a lot economic development and planning in the area, but we just don’t have the jobs,” Hollenbeck said. “It seems like every time we try to get an industry going, everybody is negative about it, so we’ve gone through a lot of ups and downs with economic development over the years, and while it shouldn’t discourage us, it does get discouraging.”

Edgemont has seen a slight bump in new people moving to town, including a couple of families from Colorado who apparently sought solace away from the big city amid the COVID-19 pandemic. As in most small towns, a lack of quality affordable housing hampers growth efforts in Edgemont.

Edgemont has not seen any known cases of coronavirus, though Fall River County as a whole has seen roughly a dozen. The pandemic, however, has led officials to close the local senior center and cancel the annual Fall River County Fair, and some local businesses have been stung by a lack of spring tourists and mandatory social-distancing rules.

Edgemont Mayor Carla Schepler, who works as a meat cutter at the Yes Way grocery, said she has seen a recent uptick in visitors passing through or stopping in Edgemont. She said a pressing issue is that the city hopes to convince the state to slow traffic on U.S. 18 that zips along the north edge of town at 65 mph and deters safe entry into the downtown area and to the Dollar Store across the highway.

But in the longer term, Schepler said the City Council continues to seek ways to strengthen the local economy and attract new services to Edgemont. The council is exploring how it might lure a medical practitioner to town on some weekdays and is also participating in the state Bulldoze, Build, and Beautify program that provides funding to tear down and replace blighted homes.

“You think of small towns and we’re kind of isolated, so it’s hard for people to locate a new business in town,” Schepler said. “Hopefully we can get some stuff turned around, and hopefully we have another boom soon.”

Stephanie Stevens came to Edgemont as a newly papered veterinarian in 1995 after scouting the area and discovering that the only vet who had been operating there for 40 years was about to retire.

Edgemont had many attractive qualities for Stevens: it was close to her family in the Rapid City area; it was quiet and safe and had a good school; and the ranching industry that dominated the local economy was sorely in need of veterinary services.

Looking back after 25 years, Stevens remains pleased with her decision.

“I’m glad I’m here; I’m glad I started here and that I stayed here,” said Stevens, a mother of two. “It’s really a good place to raise a family, I’m close to home and family in the Black Hills and in a community where it is very fulfilling to me to serve the people I do and provide the services I can.”

Business has boomed at the Cheyenne River Animal Hospital that Stevens launched in 1996, now with four staff veterinarians and a steady caseload of clients with large animals and family pets in an 80-mile radius.

“I like that it’s a ranching community, agriculture-based, which I think contributes to the quality of life in raising a family, and gives them good values and experiences,” Stevens said.

Families who live in Edgemont or might relocate there will quickly learn the benefits of the small but effective local school system, said Sue Hendricks, a math teacher who has spent 36 years in the Edgemont schools.

The school system benefits from having a low number of students growing up on ranches or in a small town, said Hendricks, 59. The 2020 high-school graduating class was only five students, but is closer to a dozen students in most years, she said.

“I like the size of the school because you know the kids, and it’s more personal, not like ‘Who are you again?’” Hendricks said. “I feel I can be a more effective teacher since I know my kids and their backgrounds. When I’m instructing, I can see the looks on their faces and you know if they’re with you or if you’ve lost them.”

Hendricks, who serves as director of the local museum during summers, said it is difficult to predict what, if anything, might jump-start new growth in Edgemont. But in the meantime, she expects the town will continue to be made up of families with deep roots and a few newcomers and a smattering of existing businesses and the occasional entrepreneurial effort.

“Who knows what industry will be like 20 years from now, but hopefully things will be better than they are now,” she said. “We’re not closing our doors and we’re not folding. We’ll just keep going on.”

— Story by News Watch reporter Bart Pfankuch.

Lake Andes recovering from flood and a pandemic

The last few decades have not been kind to the small South Dakota town of Lake Andes, and the COVID-19 pandemic has only made things more challenging.

Located within the borders of the Yankton Sioux Indian Reservation in Charles Mix County in south-central South Dakota, Lake Andes and its 826 residents have seen their share of recent bad luck.

Last year, heavy rains filled Lake Andes — the town’s namesake glacial lake — and caused it to overflow. Rising water swallowed up a park, overtopped several key roads and blocked access to the town’s new Dollar General store. Even before the flood, farm consolidation and low commodity prices had been driving down the area’s rural population and had contributed to declines in the local business community.

Population has remained almost unchanged in the past 20 years in Lake Andes, the county seat of Charles Mix County, which has a population that is about 35% Native American. The town is the proud hometown of Faith Spotted Eagle, one of only two women ever to receive an electoral vote for president of the United States.

Lake Andes, while economically dependent on agriculture, was founded partially as a tourism town. The lake itself has long been known as an angling destination, attracting summer tourists to the town for decades before the Missouri River reservoir system was finished in the 1960s.

As early as 1915, Lake Andes residents were celebrating an annual festival called Fish Days every June, in honor of the anglers who would spend part of their summers in town.

The Fish Days celebration was discontinued in the late 1960s as anglers turned their attention to the Missouri River reservoirs (the event was later revived in the mid-1980s). But even through the 1970s, Lake Andes was doing pretty well for itself.

“When I was a little girl we had a lot of businesses on the street,” said lifelong resident Debbie Houseman. “We were, I’d say, a fairly thriving community. We had a bus depot, we had a movie theater, two grocery stores, a restaurant on Main Street, a bakery, a hair salon, you know, the street was full.”

But as in many South Dakota small towns, the economy began to falter as population losses mounted, Houseman said. Between 1980 and 2018, the population declined from 1,029 to 826, a roughly 20% drop.

“I think like a lot of little towns you know, as kids graduate, there aren’t jobs here for them, so they leave and you don’t retain that population,” Houseman said. “You see that happening with a community like ours.”

The town found itself in a new battle when the flooding hit last year. Still, the community began to recover and things were looking up in February 2020. The town’s leaders were beginning work on repair projects they hoped to pay for with disaster assistance from the Federal Emergency Management Agency, said City Finance Officer Debbie Houseman. The dollar store was back open and the local grocery store’s new owner finished some much-needed improvements.

“I think like a lot of little towns you know, as kids graduate, there aren’t jobs here for them, so they leave and you don't retain that population. You see that happening with a community like ours.” -- Debbie Houseman, Lake Andes finance officer

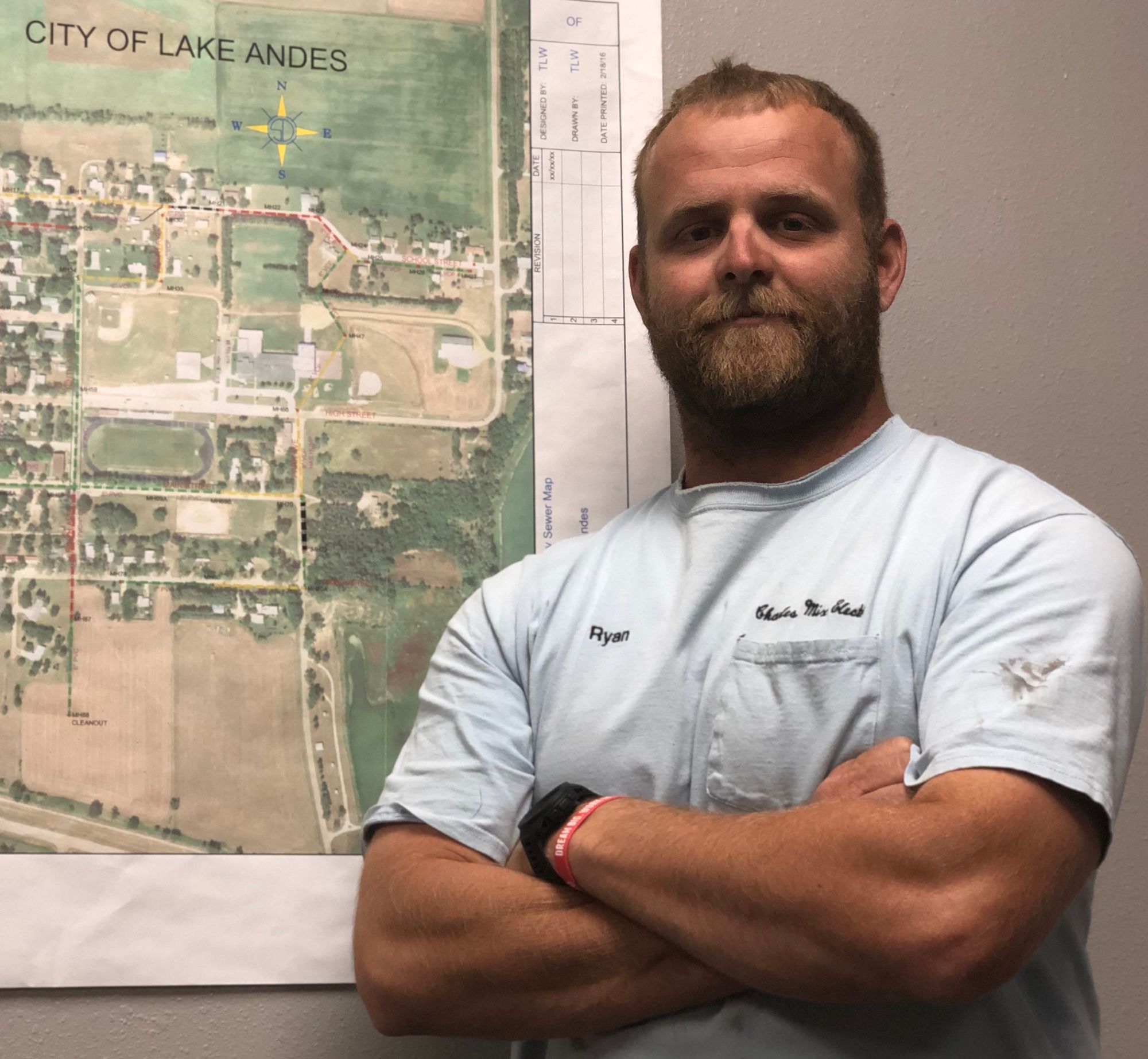

Then came COVID-19. Lake Andes Mayor Ryan Frederick vividly remembers the town’s first brush with the deadly disease. In early March, he attended a meeting at the nearby Fort Randall Casino to figure out how to lower Lake Andes water levels and reduce the risk of future flooding. After the meeting, rumors started to spread that one of the attendees had been exposed to COVID-19.

“Then it was just complete chaos, because people are trying to figure out who was there and what you would have touched and all that stuff,” Frederick said.

About a week later, South Dakota Gov. Kristi Noem issued executive orders outlining steps cities and towns should take to slow the spread of COVID-19. Lake Andes, though, took its time to craft and pass an ordinance shutting down nonessential businesses and bars. The town’s ordinance took effect on April 22, Frederick said. But citizens had already drastically changed their routines.

“I think people were just scared,” Frederick said. “There weren’t people moving around or really doing anything. I mean, people were just staying in, doing their social distancing.”

Still, the city government’s ordinance ordering nonessential businesses to close was a tough sell, Frederick said.

“It was a tough decision to do that as a council because you have a business owner, two business owners, and that’s their livelihood,” Frederick said. “But you’ve got to protect the people. We didn’t want to get COVID here and just have it spread like wildfire.”

The ordinance was repealed on April 30 and by mid-June, Frederick said, the town and its residents had mostly gone back to business as usual.

The Circle H motel and campground was doing brisk business in mid-June. The motel is located on the south side of Lake Andes where U.S. 281 turns southeast toward the Missouri River in a good spot for anglers to wet a line.

Mary Snyder and her husband, Larry, sold their farm and bought the motel 18 years prior to the COVID-19 pandemic

“It was the river, the area’s good pheasant hunting and it’s close to my family,” Snyder said.

The motel saw a steady stream of customers throughout March, April and May thanks to nearby wind farm construction and out-of-state contractors working on area highways, Snyder said. But she was a little worried the virus might affect the motel’s busiest season in summer.

Nearly all of the Circle H’s summer business comes from Iowans and Nebraskans hauling boats west for long fishing weekends on the Missouri River. Many are repeat customers and have become good friends over the years, Snyder said. But the flooding in 2019 kept many nonresident anglers away. Spring of 2020 started off pretty slow, too.

“We had to postpone our annual walleye tournament,” Snyder said.

Most of the Circle H’s employees are Snyder’s granddaughters, so making payroll wasn’t a big problem. By the end of May, anglers from surrounding states were starting to show up. As it turns out, the 2019 flood may well have improved fishing on the Missouri River. And Lake Andes itself has been stocked with walleyes in each of the last three years, Snyder said.

By the middle of June, the Circle H’s campground was mostly full and many of its rooms were occupied. Any concern Snyder had about her motel’s future had dissipated. As long as there were fish in the Missouri, Snyder said, there would be customers for her motel.

“It’s quite a God-given blessing to us, that river,” Snyder said.

The return of anglers has contributed to one of the pieces of good news arising from the pandemic, Houseman said. The South Dakota Department of Revenue reported in June 2020, that Lake Andes had actually seen a 7% increase in sales tax collections during the first five months of the year compared to 2019. Houseman attributed much of the sales tax bump to more Lake Andes residents shopping for groceries and other essentials closer to home.

For Mike Dangle, who works for Charles Mix Electric, the rural electric co-op that serves Lake Andes, the pandemic hasn’t been much more than a minor inconvenience. His family was able to get everything they needed locally and was even able to get their kids’ school work completed through the internet.

Dangle grew up in Irene, a small town about 75 miles east of Lake Andes. It was his work for Charles Mix Electric that brought him and his family to the town more than two decades ago. They now live on a small hobby farm a few miles north of Lake Andes.

The social distancing has been the toughest part of the pandemic so far, Dangel said. Small towns such as Lake Andes are built on relationships and not being able to meet in person or attend church has been isolating. But, on the whole, Lake Andes has been a great home town, Dangle said.

“It’s a great community to live in,” he said. “There’s a great small town atmosphere and everyone knows each other.”

— Story by News Watch reporter Nick Lowrey