Editor’s note: This is the first of a four-part series on expansion of CAFOs in South Dakota.

The livestock industry in South Dakota — among the state’s largest economic engines — is undergoing a fundamental transformation that may alter farms, farmers and rural communities for generations to come.

Despite a rising wave of grassroots opposition, South Dakota is seeing a steady increase in the development of livestock operations known as CAFOs, or concentrated animal feeding operations, in which thousands and sometimes more than a million animals are bred, housed and fed in a confined space.

Supporters of CAFO development say the farms can boost the state’s agricultural economy and strengthen rural communities. Opponents say the farms are causing division among rural populations and will limit opportunities for non-agricultural development in small-town South Dakota.

The state has seen a nearly 15% rise in the number of CAFOs in operation over the past decade, and the pace of development has picked up recently, with 18 new CAFOs put into production over the past 18 months.

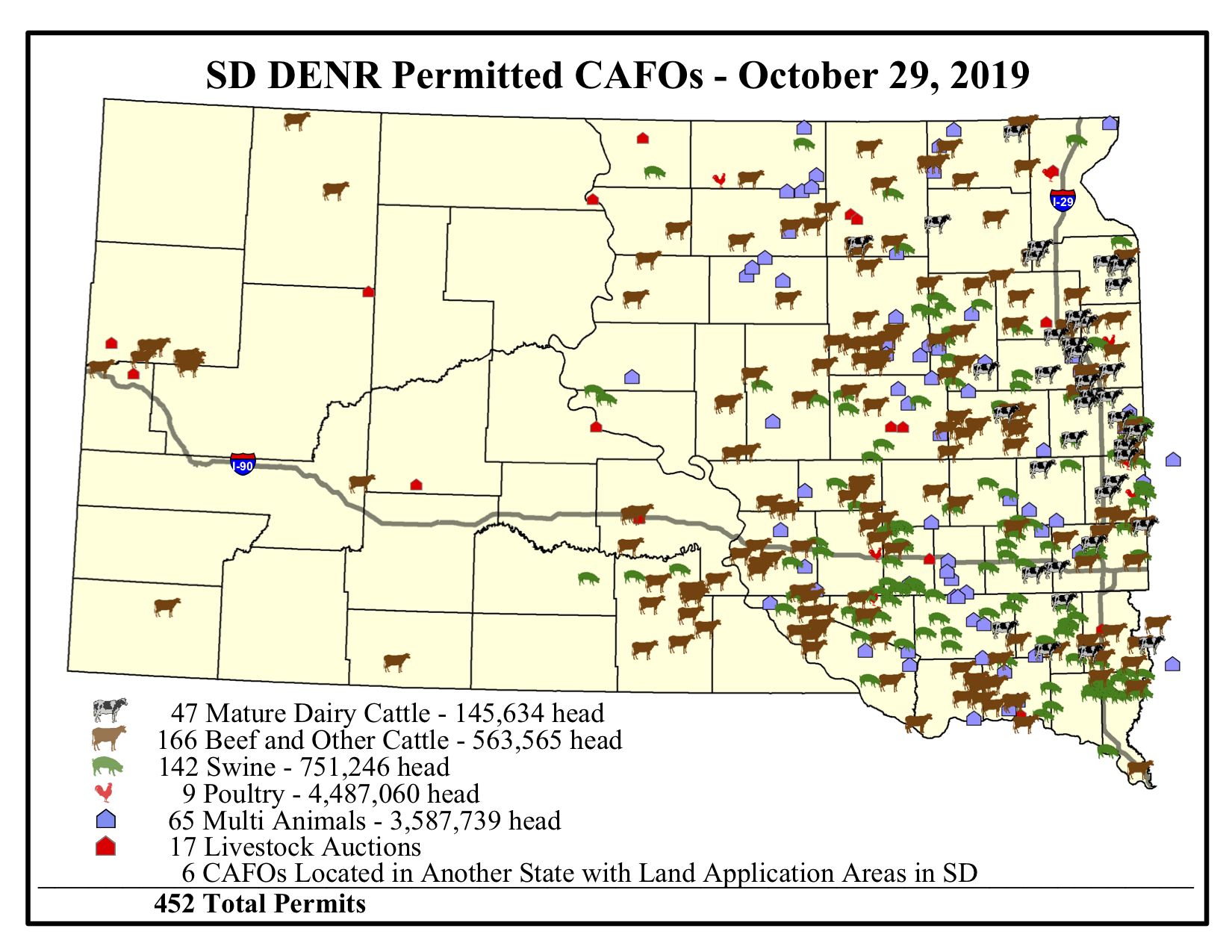

As of October 2019, there were 452 permitted CAFOs allowed to house about 9.6 million cows, hogs, turkeys and chickens in the state, according to the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources.

When it comes to CAFO development, the stakes for South Dakota are high in terms of both risk and reward.

Supporters of the farms — including Gov. Kristi Noem — see strong opportunity for expansion of the livestock and related products market, which accounted for $4.5 billion in sales in 2017, about half of the state’s total agricultural economy.

A single hog-birthing facility recently approved for a rural site south of Miller in Hand County, for example, is expected to create 19 full-time jobs with an annual payroll of $1.3 million and produce another $1.3 million in annual feed purchases.

But each new large livestock operation brings environmental and odor concerns, and for some, emotional heartache and health problems.

Lyle Reimnitz, who lives a half-mile from a Davison County hog farm permitted for 8,000 sows, said the odors and gasses from the farm prevent him from living a normal life. He and his wife suffer from headaches and respiratory problems, they rarely sit outside or hang out laundry, and they have given up on their dream of having their daughter’s family move to the farm when her husband retires from the military.

“It doesn’t smell every day, but in the evenings, especially when the wind goes down and the humidity is high, we stay inside and keep our windows shut,” said Reimnitz. “The manure pits have gasses in them, and it gives me headaches, my eyes burn and I start coughing. My doctor said if I breathe it long enough, I will end up with respiratory problems.”

Reimnitz and others fear that if livestock confinements continue to develop rapidly in South Dakota, the state may follow the path of Iowa, the national leader in large hog farms where consistent odors, waterway pollution and fish kills have resulted from heavy CAFO development.

“I don’t want to see South Dakota become another Iowa,” he said. “We don’t need all our rivers and streams polluted. I know everybody wants cheap meat, but that comes at a terrible price for people who live here.”

Each time a new CAFO project is proposed, it invariably faces objections from some neighbors and environmentalists who raise concerns over human health risks, reduction of property values, animal treatment and antibiotic use, odors, and fears of potential contamination of air, land and waterways from high volumes of animal waste.

Yet, at the same time, the state of South Dakota this year started a new effort to provide a major financial incentive to county governments that approve new CAFO projects.

Industry groups and some state officials say CAFOs provide new opportunities for existing farmers, create options for young farmers to get started and add significant financial value to the state’s largest industry.

“I do think we need more ag development in South Dakota,” Gov. Noem said in an interview with News Watch in September. “Anytime we can add value to the commodities and livestock that we raise here, it puts more money into South Dakota’s pocket and for those producers out there that are working so hard to feed the world.”

Operators and industry groups say large livestock farms are generally well run and are subject to strong permitting processes and regular inspections that don’t apply to smaller farms.

Noem said she will continue to support CAFOs as long as they are properly sited and operate within state guidelines.

“I actually live right down the road from a large dairy that has thousands of head of dairy cattle, and I’m a rancher too,” Noem said. “The smart thing is to make sure we’re putting these in the right locations, that we’re protecting our resources, and that we’re protecting our environment and putting them in areas where economic development can grow. Agriculture is our number-one industry and if we can add value to those products right here, that is a win for everyone.”

Livestock industry scaling upward

The vast majority of American livestock is now raised in CAFOs, with federal data showing that about 70% of cows, 98% of pigs and 99% of chickens and turkeys are produced in CAFOs each year.

The farms differ from traditional livestock farming in the number of animals raised and where and how they are kept.

Large CAFOs are farm operations that require a state permit and are subject to regular inspection once they reach 1,000 or more “animal units.” Based on weight, 1,000 animal units equates to either 700 dairy cows, 1,000 head of cattle, 2,500 adult hogs or 10,000 juvenile swine, 55,000 turkeys, 82,000 laying hens or 155,000 chickens.

Rather than feeding and holding animals in fenced fields, outdoor pens or open barns, the animals are kept en masse in large barns that often are segregated into smaller pens inside. Animals typically are not exposed to the sun or the elements, usually live on concrete slabs or metal slats, and sometimes stand almost shoulder-to-shoulder, especially as they age and grow closer to harvesting weight.

South Dakota has increasingly become a magnet for CAFO development by both existing local farmers and out-of-state firms that partner with local landowners and investors to implement well-defined systems of animal birthing, feeding and housing. South Dakota, particularly in the east, is attractive for CAFO developers owing to access to inexpensive feed, solid infrastructure, available land and close proximity to major slaughterhouses and processing plants. The state is bordered by three states that are top-five in the nation for number of large CAFOs — Iowa, Minnesota and Nebraska.

CAFOs provide farmers with a way to produce a high-volume, valuable and stable crop of animals in a climate-controlled setting with low capital costs for equipment and land. The development of CAFOs is also generating new jobs, state and local tax revenues and significant spinoff spending on feed and other commodities. The ultimate result is affordable meat for a growing population of consumers in the U.S. and across the world.

Hog production is rising in South Dakota and much of the increase is taking place in concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, in which thousands of hogs are held within huge barns and not allowed to roam. These hogs are located in a CAFO at the Oak Lane Hutterite Colony in Hanson County. Click the arrow in the image to watch a montage of animals housed in South Dakota CAFOs, including turkeys, hogs, beef cattle and dairy cows. Photo and video by Bart Pfankuch, South Dakota News Watch.

CAFOs in the Great Plains

Here is a look at 2018 data from the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency listing the number of concentrated animal feeding operations with 1,000 or more animal units by state in the Great Plains, and the percentage of those operations that have a federal wastewater-discharge permit that provides regulations on how and where wastewater can be spread.

State CAFOs % with federal permit

Iowa 3,744 5%

Minnesota 1,400 79%

Nebraska 1,207 36%

South Dakota 431 100%

Montana 124 83%

North Dakota 76 0%

Wyoming 49 82%

United States 20,382 32%

CAFOs can be found in all U.S. states except Alaska, Hawaii and Rhode Island; the top five states for large CAFOs are Iowa (3,744), Minnesota (1,400), North Carolina (1,222), Nebraska (1,207) and California (1,083).

Agricultural organizations say CAFOs are part of an ongoing advancement in efficiency of handling and raising animals. They also stress that the vast majority of CAFOs and other farm operations in South Dakota remain owned or operated by families.

“Agriculture has been changing for 100 years, and just like the four-row planter became the 16-row planter and then the 20-row planter, the common theme is that there’s still a family that is out there doing it,” said Steve Dick, director of Ag United, a Sioux Falls organization that represents farmers in several agricultural sectors in South Dakota. “And I don’t know if hogs or cattle being in a confined space has changed. I think what has changed in the last 10, 15 or 20 years is the technology for the comfort of those animals.”

Farmers and industry officials say that in order to make a good living in the modern agriculture industry, getting larger and creating economies of scale is one way to find success.

“The days of having a few chickens, a few milk cows, a few cows, those days have changed a lot as [livestock] farmers have specialized in one species, just as a lot of farmers have specialized in corn or soybeans,” Dick said.

Supporters and producers also say the growth of large livestock operations that produce cheap meat is being driven by consumers, not farmers.

“This is what we’re getting pushed into doing; we’re not driving our own market, it’s demand,” said Brian Alderson, a part-time cattle farmer who raises about 600 head in a CAFO-style barn in western Minnehaha County. “You tell us what you want us to do when you go to the grocery store. It’s supply and demand, and the consumers make the rules, not us.”

But opponents worry that aggressive development of CAFOs, particularly by out-of-state firms, will change the nature of farming and rural living in South Dakota.

“Industrial CAFOs that store manure under their operations for 365 days before spreading are a separate agricultural business than compared to grazing animals that are not confined, not under a roof, but are under the sun and the air where they can naturally distribute the manure that makes it a positive, instead of a toxic overload,” said Candice Lockner, a Ree Heights rancher who fended off a proposed 50,000-head cattle CAFO in her neighborhood in 2014 and has since become a grassroots organizer against the farms. “If we want to have strong rural communities, we should have farms that have family farmers who care about the animals in a way that is environmentally sound and is regenerative and sustainable.”

Research done mainly in North Carolina and Iowa has shown that large livestock operations can cause health problems in workers in the farms and to neighbors. One study found that children who live or attend school near large livestock operations suffer from higher rates of asthma. The farms emit high levels of ammonia and hydrogen sulfide that can harm humans, the research has shown.

So far, South Dakota has avoided major environmental disasters from large livestock farms.

According to data obtained through a public-records request by News Watch to the DENR, permitted CAFOs in South Dakota violated state regulations 217 times from October 2009 to August 2019 and $207,000 in fines were levied. Violations led to farm wastes making their way into state waterways nine times during that period, but little or no environmental damage resulted, DENR officials said.

Further expansion of CAFOs likely in SD

Development of new large livestock farms and expansion of existing farms can result in large payments to counties that approve them under a new tax-rebate program started by the Governor’s Office of Economic Development in spring 2019.

The program is not the first time the state has tried to encourage counties to approve new CAFOs. In 2013, the state Department of Agriculture embarked on a program to use Geographic Information Systems data to provide each county in the state with a report on which areas would be appropriate for new agricultural operations, specifically including CAFOs.

Just as worldwide demand has led to more mechanized livestock production, changing consumer desires have also led to an increase in organic and sustainable farms that eschew the use of antibiotics and hormones and raise animals in a free-range setting. Recent research shows that the millennial generation, in particular, has a desire for more organic and sustainable agricultural products.

The website for the group EatWild, a consortium of sustainable farms in South Dakota, lists 15 farms that feature only grass-fed, open-range livestock. A 2017 report on farm size by South Dakota State University indicated a 57% increase in the number of farm operations with 100 or fewer acres.

However, such farms still make up only a small fraction of farms in the state overall.

Farm size and production data also illustrate the rapid growth in the largest farms in South Dakota, both in row cropping and in livestock. SDSU found that farms with more than 2,000 acres took up almost 67% of the state’s total cropland in 2017, compared with only 48% in 1997.

South Dakota has seen a steady increase in the number of CAFO operations permitted by the state since state regulation began in 1997, from 15 that year to 338 in 2007 to 452 as of October 2019.

State data also show that the number of animals allowed at those operations has also increased significantly in recent years, from 8.4 million animals at 400 permitted operations in January 2011 to 9.8 million animals at 443 permitted operations in January 2019.

The majority of the recent growth has occurred in the hog industry, which has seen a 21% increase in permitted operations from 2011 to 2019 and a 32% rise in the number of permitted animals during that time.

The largest CAFO operations in South Dakota include the National Foods egg hatchery east of Plankinton in Aurora County with 1.98 million chickens; the Schlitz Goose Farm in Sisseton with 193,000 geese; the PIC Apex Farm in Mound City in Campbell County, with 36,400 sows; and the Fall River Feed Yard southeast of Hot Springs in Fall River County with 25,000 head of beef cattle.

Hog farming has grown significantly in scale in recent years, and statistics reveal the impact of CAFO growth on the industry. While the number of hog farms overall in South Dakota has fallen by 16% from 2012 to 2017, the number of large farms producing 5,000 or more hogs per year has jumped by almost 30% over that period.

In 2012, the state had 145 large hog farms that produced 3.6 million hogs valued at $390 million, according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture Census of Agriculture. In 2017, 188 large farms produced 5.2 million hogs valued at $545 million, the USDA said. Also, the USDA data show that 20 of the 85 largest hog farms in South Dakota are operated by contract farmers or integrators, indicating the growing push into the state by outside interests.

The concerns over involvement of non-local CAFO system providers are misplaced, said Nick Fitzgerald, business development manager with the Pipestone System, a Minnesota-based firm that works with landowners and investors to start up and operate hog facilities in seven Midwestern states, including South Dakota.

Pipestone operates 74 hog birthing and weaning facilities, including more than 20 in South Dakota. The company provides new hog farmers with siting expertise, management training and full production systems to raise hogs.

Fitzgerald said the firm, started by a group of veterinarians in Pipestone, Minn., employs a proven method of farming that engages safeguards for animal safety and protection of the environment.

“We want to be great neighbors, and we don’t want to be an environmental risk in any way, shape or form,” Fitzgerald said.

Pipestone will likely continue its expansion in South Dakota, which has inexpensive feed, including corn and ethanol byproducts, Fitzgerald said.

“In terms of setbacks and siting, South Dakota is more strict than other states,” Fitzgerald said. “But we would like to raise more pigs in South Dakota because we can raise them at a lower cost than in the state of Iowa, for example.”

Industry experts say there is more room for growth in American hog production, particularly due to growth in the foreign market. Iowa, for instance, passed the $1 billion mark in exports of hogs to China and Hong Kong alone in 2016.

South Dakota is also likely to see strong growth in dairy cattle CAFOs, especially in the far northeast, to accommodate expansion in the cheese-making industry. The Valley Queen Cheese company in Milbank, Dimock Dairy in Dimock and the Agropur cheese plant in Lake Norden all underwent significant expansion in 2019. The tripling of capacity at Agropur alone will require milk from 85,000 more cows in the region, the company said.

The expansion of CAFOs in South Dakota may also be hastened by a need for room for expansion within the livestock industry in the Great Plains.

South Dakota is flanked by three states that are in the national top five for number of large CAFOs — Iowa at No. 1, Minnesota at No. 2 and Nebraska at No. 4.

David Osterberg, who has studied CAFOs in Iowa for three decades for the Iowa Policy Project, said South Dakota should expect to see even more CAFO projects proposed as those neighboring states reach a saturation point for CAFOs, with dwindling land where CAFO wastes can legally be spread.

“It makes sense they are moving into South Dakota, because we’re running out of room to put the manure over here,” said Osterberg. “Especially in the northwest of Iowa toward you guys, there are so many CAFOs that finding a place to get rid of the manure is getting difficult.”

Regulation higher on largest CAFOs

Even though CAFOs can generate millions of gallons of cattle and hog manure and thousands of pounds of litter from turkeys and chickens, industry and government officials say CAFOs can be cleaner than smaller farms.

The animal wastes created by CAFOs are collected and held in lagoons or huge underground tanks and then are spread onto nearby farm fields as fertilizer. Spreading typically takes place when the frost breaks in spring and before the ground freezes in fall. Farmers use trucks to haul wastes or flexible pipes that run for miles to get the liquid manure to nearby farm fields, where it is forced into ground dug up by a discing machine. The days when the manure is spread are the most malodorous.

The manure is an effective, valuable fertilizer that reduces the need for commercial fertilizers; CAFO operators are typically paid for the nutrient value of the manure by crop farmers.

Regulation of large animal-feeding operations in South Dakota is based on the federal Clean Water Act, which became law in 1972, and subsequent livestock laws that were developed by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency in 1974.

The state began regulating animal-feeding operations beginning with hog farms in 1997 and adding other animal types in 1998. The CAFO permit rules were updated in 2003 and again in 2017.

CAFOs in South Dakota are subject to far more regulation than smaller farms. Once a farm reaches CAFO status, it must obtain a state permit that provides for regulation of waste management and water use, said Kent Woodmansey, who oversees the CAFO inspection program within the state DENR. CAFO operators must attend a producer training class to become educated on state regulations and monitoring requirements, he said.

New CAFOs are inspected within the first 18 months of operation and then every one to three years after, depending on size, Woodmansey said. Inspections are announced in advance so operators can prepare and in some cases arrange to have their outside waste management consultant present, Woodmansey said. “Otherwise we drive out there and they’re not there,” he said.

CAFO operators are held to strict standards on proper storage of wastes, with a close eye on their not overreaching the capacity of waste-holding ponds or lagoons that are typically lined with clay or concrete. Soil testing is done, and operators must adhere to plans for how, when and where they will spread the wastes, Woodmansey said.

State regulators will also make contact with an operator or inspect the operator’s property if they receive a formal, signed complaint from the public. Most complaints relate to concerns over potential contamination of water sources and the spreading of wastes, he said.

The state also receives complaints about odors, but has no authority to monitor or take action against strong odors because no state or federal law regulates smells released by agricultural operations, including CAFOs.

“We won’t respond to an odor complaint because we don’t have any criteria for that,” Woodmansey said. “If somebody sent something in about odors or called about that, we would respond that we have no authority over that.”

South Dakota CAFOs also must gain approval, typically in the form of a conditional-use permit, from county commissions or planning and zoning boards before being built. That process provides a level of local control not in place in states such as Iowa.

Counties can have a range of local rules and guidelines, the most important being the “setback” limits on how close a CAFO can be to residences, municipalities and water sources. The limits can vary from county to county, and undergo fairly frequent updates.

The new hog farm in Hand County has a two-mile setback requirement from any residence and 660 feet from any ground or surface water supply. Voters in Grant County passed a referendum in 2016 to double the setback from homes of new large CAFOs from a half to a full mile. Meanwhile, the Minnehaha County Commission in 2017 reduced the setback from buildings for new feeding operations of 2,000 or more animals from 4,620 feet to 3,960.

CAFOs also face significant scrutiny at the county level and are sometimes rejected.

The Hamlin County Board of Adjustment in May 2019 rejected a proposal for a 10,000-head dairy CAFO in part because a well was discovered within a half-mile of the farm.

Yankton County has had an embattled history with CAFOs and the zoning and approval processes. CAFO proposals have faced strong opposition; a few that were approved faced a lawsuit. Over the years, the county has floated a special zoning designation to allow CAFOs, but is now considering a full moratorium on CAFO development.

At least 20 counties in Iowa have passed resolutions to ban further development of large livestock farms, but the measures are virtually meaningless because only state approval is needed for CAFO development in that state, Osterberg said.