On the night of Sept. 21 in Washington D.C., Kristi Noem’s face appeared on a video screen at an event hosted by the Media Research Center, a conservative watchdog group that aims to “expose and neutralize the propaganda arm of the left: the national news media.” The organization was celebrating its 35th anniversary with a black-tie gala at the National Building Museum and promised to “honor those who have stood up to the left-wing mob.”

South Dakota’s governor was a featured speaker.

Noem, who had planned to attend in person, said her travel was curtailed by back surgery at the Mayo Clinic earlier in September for an acute condition of her lumbar spine. She submitted a videotaped message that echoed the media-bashing mantra popularized by her political ally, former president Donald Trump.

“What we did during the [COVID-19] pandemic worked, even though the liberal media tried to prove otherwise,” Noem told the audience. “So now they have their sights on me in all kinds of ways. They’re attacking my family, they’re attacking every decision that I make, and they’re trying to tear South Dakota down. But that isn’t going to happen. Not on my watch.”

It’s hard to imagine recent South Dakota governors Dennis Daugaard, Mike Rounds, or even the irascible Bill Janklow uttering those words on a national stage – or having the opportunity to do so. But Noem has found the national spotlight, building a brand of right-wing populism unrecognizable in many respects from her career before Trump became president and the pandemic made polarization and personal attacks common in American discourse.

Noem’s supporters laud her laissez-faire approach to pandemic response and cite her national profile as positive for selling South Dakota as a land of opportunity rather than a flyover state. Business applications increased by 6.4% in August, the highest rate in the nation, according to the U.S. Department of Commerce, and the unemployment rate stands at 2.3%. South Dakota ranked second in the amount of state-to-state migration that was inbound (69%) rather than outbound in 2021, according to Atlas Van Lines.

Critics accuse Noem, who is up for re-election Nov. 8, of being hypocritical, among other concerns. She talks of less government while South Dakota reaps the benefits of millions in federal COVID and infrastructure funds, re-branded as state-level stewardship. She touts her “no lockdown” pandemic record despite closing schools in the spring of 2020 and proposing laws seeking more authority for state and county health officials to shutter businesses that violated CDC guidelines. And she lavishes praise on Trump despite saying in 2015 that some of his stances were “un-American” and that he was “not my candidate.”

So what does Noem really stand for? It might depend on whom, and when, you ask.

“She’s like a political chameleon,” said Lance Russell, a former state legislator from Hot Springs who also served as executive director of the South Dakota Republican Party. “I don’t think she’s ever really shed her establishment mentality, but she’ll shift her views or positions if she sees that someone or an idea is popular. She can very easily transition.”

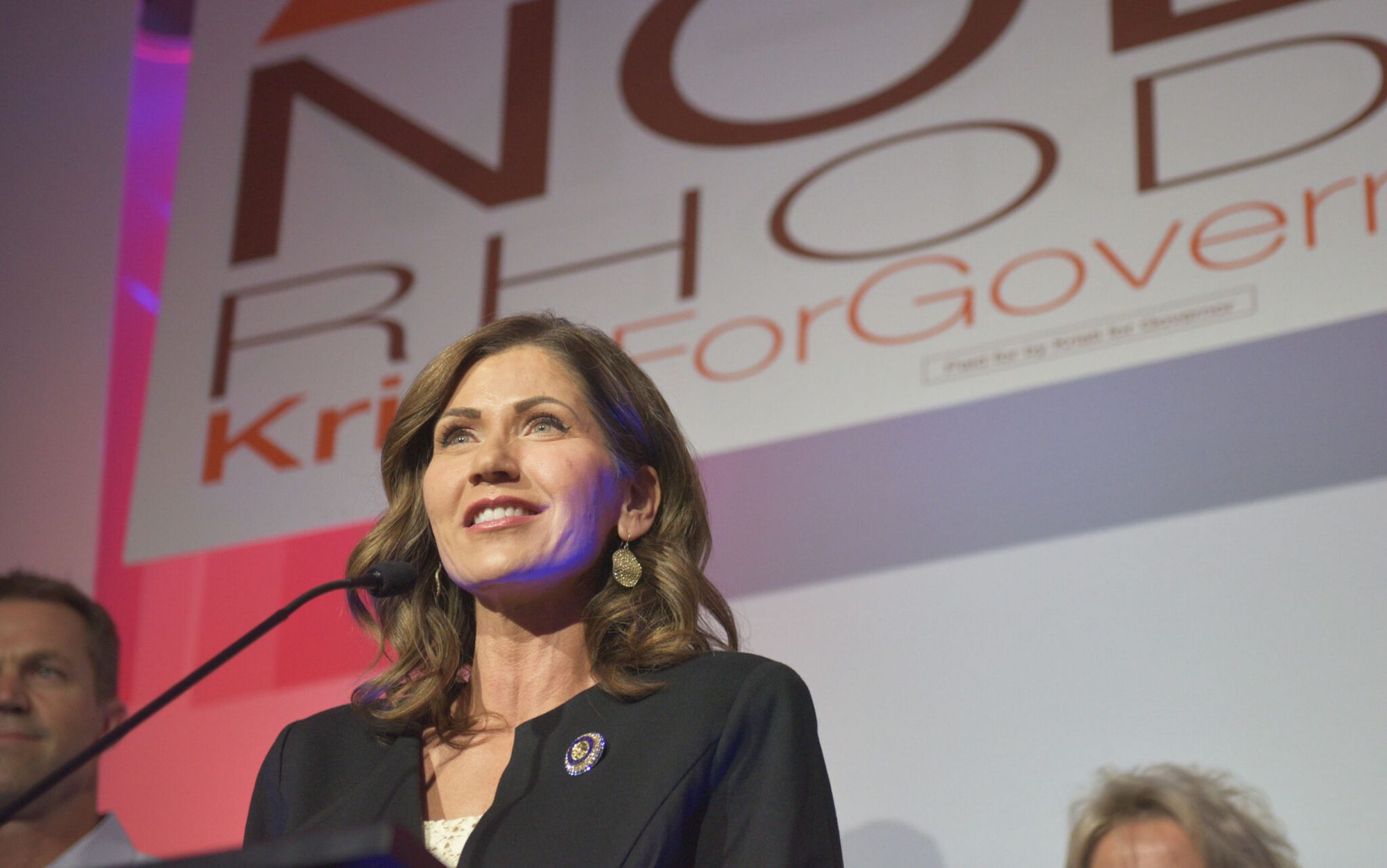

Noem didn’t agree to an interview request for this story, deferring questions to spokesperson Ian Fury. South Dakota News Watch reached out to political scientists, lawmakers and campaign experts to assess the steps and strategy of the governor’s journey from farm-raised Hamlin County candidate – a former Snow Queen with agricultural business acumen and a compelling personal story – to one of the most polarizing figures in South Dakota political history.

One thing is clear: Noem’s pursuit of Republican Party relevance and extreme positions on hot-button issues such as abortion and gun rights make it nearly impossible for state residents not to have strong opinions of her, whether cheering her for a flag-waving horseback ride or chuckling at her in a Saturday Night Live lampoon in the opening sketch of its Oct. 1 season premiere.

“There’s this thing called confirmation bias that says we look for information that fits our previously held beliefs, and we often reject others’ information, or don’t even see it, in the current media environment,” said Michael Card, an emeritus professor of political science at the University of South Dakota. “That beats the heck out of dealing with the vicissitudes of, how do we make sense of all this? It’s a lot easier just to say she’s all good, or she needs to go.”

Though the 50-year-old Noem remains non-committal about aspirations to run for president in 2024 or to make the national ticket as a vice presidential nominee, her national travel and fundraising activities – she had $7.8 million in her state campaign committee as of the last reporting date – point to someone putting themselves in position to make that leap. In addition to visiting early Republican primary states such as Iowa, New Hampshire and South Carolina, Noem has held a fundraiser at Trump’s Mar-a-Lago resort in Florida, spoken in Dallas at the National Rifle Association convention (days after a deadly mass shooting at a Texas elementary school in May of 2022) and recently appeared in Arizona with GOP gubernatorial candidate Kari Lake, who supports Trump’s baseless contention that he won the 2020 election.

Noem published a book, “Not My First Rodeo,” earlier this year, capitalizing on her political bounce from the summer of 2020, when her hands-off approach to COVID restrictions and criticism of social justice demonstrations endeared her to Trump – who visited Mount Rushmore for Fourth of July fireworks – and led to a speaking slot at the Republican National Convention. Two days after Trump lost the November 2020 election to Joe Biden and started making unfounded claims about voter fraud, Noem complained about “rigged election systems” from her Twitter account.

If Trump runs again in 2024, there may not be a lane for Noem, who has polled around 1% in most national GOP primary polls so far. But her anti-lockdown pandemic stance, which led to regular appearances on Fox News and other conservative outlets, offered a glimpse of a political future beyond South Dakota’s borders.

“Trump is one variable, but I do think COVID matters,” said Jon Schaff, a professor of government at Northern State University in Aberdeen. “When the pandemic hit, her response to it raised her profile. I suspect at that point the idea struck her that maybe she could be a national contender. She was getting a lot of publicity, she’s an ambitious person, she’s a very good politician and fundraiser, so maybe that which seemed implausible or not even on her radar took on some degree of plausibility. So at that point, how does one advance in the Republican Party? You’ve got to be on Team Trump. It’s not the only way, but it’s the easiest way.”

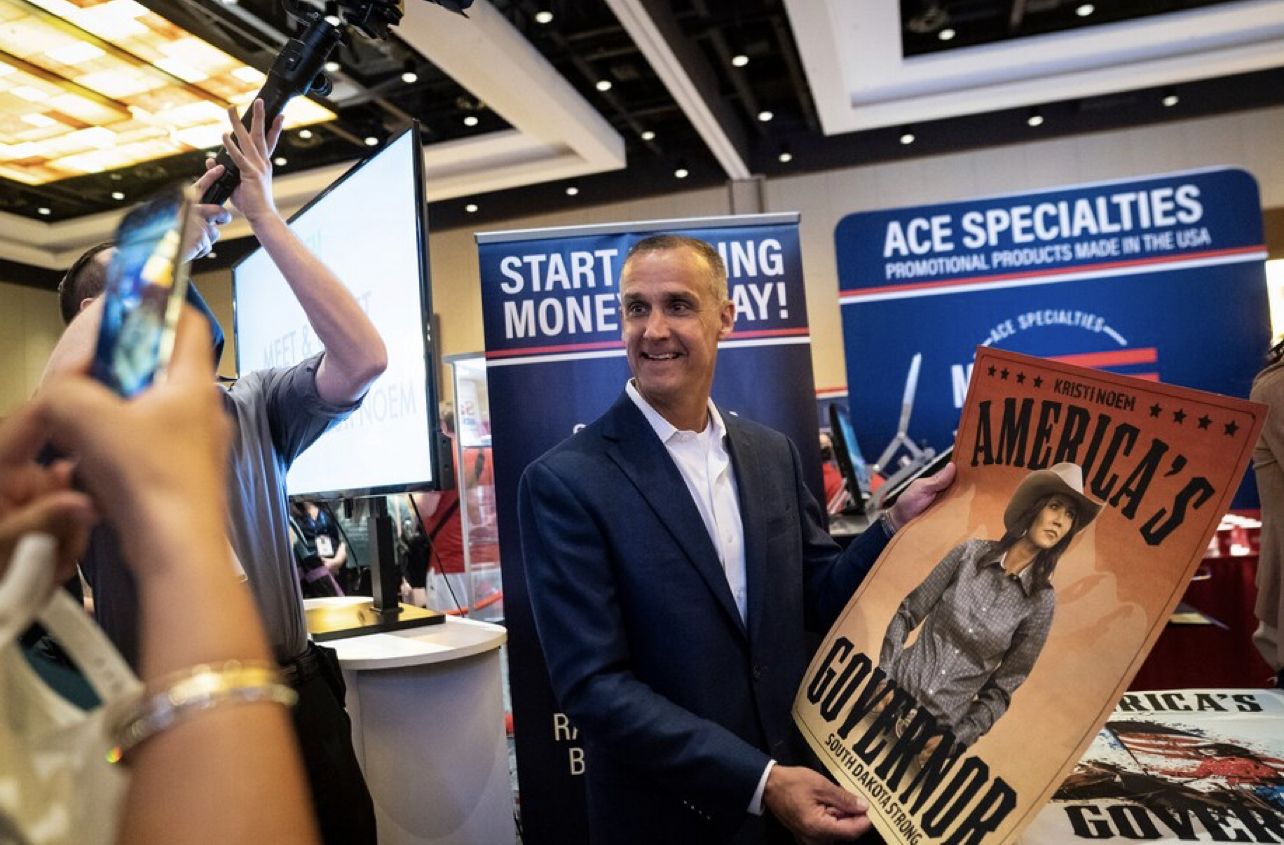

Paving the way was Corey Lewandowski, a former Trump campaign manager who helped orchestrate Noem’s travel schedule, fundraising and messaging on what the governor’s team calls a volunteer basis, but who does not come without baggage.

Lewandowski was charged with misdemeanor battery last year after being accused by a female Trump donor of unwanted sexual advances at a Las Vegas fundraiser also attended by Noem, charges that will be dropped if he follows through on a deal with prosecutors that includes eight hours of “impulse control” counseling. Noem publicly cut ties with Lewandowski soon after the incident but has since welcomed him back to the fold, and he attended a Rapid City event on Sept. 28 at which the governor promised to repeal the state’s grocery tax if re-elected, despite opposing such action during previous legislative sessions.

Noem has defended South Dakota’s abortion laws being among the most restrictive in the nation, with no exceptions for rape or incest, despite a recent News Watch poll showing that 76% of respondents support such exceptions. That stance, combined with much-publicized efforts to ban Critical Race Theory-style curricula and transgender sports participation in South Dakota schools, has opened her to criticism of prioritizing nationally resonant GOP issues over more pressing homegrown concerns.

“Governor Noem’s position as a national figure can be a positive for South Dakota,” said Republican Attorney General nominee Marty Jackley, who lost to Noem in a 2018 primary for governor. “But it’s important for anyone in a statewide role not to let national policy set your South Dakota agenda. You need to let South Dakota’s agenda set your national policy.”

State concerns are plentiful: South Dakota ranks 48th in average salary across all occupations ($44,960), according to the U.S. Bureau of Labor Management, which contributes to just 53% of state university graduates taking jobs with in-state employers. A lack of state funding for early education on the heels of the pandemic has triggered what experts call a childcare crisis at a time when nearly half of students in Sioux Falls meet the criteria for free and reduced lunch. South Dakota, one of just 12 states that hasn’t expanded Medicaid to broaden insurance coverage for low-income individuals, contains some of the most poverty-stricken counties in the United States, a reminder of the challenges faced by Native Americans and reservation communities.

“When Kristi Noem wakes up every morning, she thinks about herself and her political future,” said Steve Hildebrand, who served as Barack Obama’s deputy campaign manager in 2008 and now runs Promising Futures Fund, a Sioux Falls nonprofit that fights child poverty. “She does not wake up every morning and think about what’s best for South Dakota.”

Noem had an approval rating of 58% in the most recent Morning Consult poll, but the ultimate test comes at the ballot box as she tries to fend off Democratic challenger Jamie Smith, minority leader in the South Dakota House. The race is rated “Solid R” by the nonpartisan Cook Political Report, but a recent South Dakota State University poll had Noem’s lead (45% to 42%) within the margin of error, drawing comparisons to her surprisingly tight victory over Billie Sutton in 2018.

Noem and her supporters have tried to portray Smith, a state legislator, realtor and former educator from Sioux Falls, as a “radical leftist” who is closely aligned with Biden’s agenda. Smith has countered by calling her views on abortion extreme, questioning her ethics, and pointing to Noem’s focus on national political themes rather than kitchen-table concerns.

South Dakota hasn’t had a politician run for president since George McGovern in 1972, though senators Tom Daschle and John Thune reportedly considered campaigns before turning back. It takes an element of self-regard, considered a prideful flaw in some corners of the state’s psyche, to reach for higher office, yet Noem has shown impeccable timing in her career and an ability to close out elections, with a record of 7-0. In that respect, say her supporters, she has been consistent in her approach.

“Kristi got into politics 16 years ago, and we’ve seen this country change a lot in that time,” said Tony Venhuizen, who worked in the Daugaard and Noem administrations and is headed to the state legislature as a Sioux Falls Republican. “I’m not sure that she’s really changed all that much. She has stepped up to the challenge and gone where she felt God was leading her, which meant stepping up into positions that I don’t think she would have ever guessed she would find herself in.”

Disparate views on Gov. Kristi Noem

From Tony Venhuizen of Sioux Falls, former Noem chief of staff and presumptive Republican lawmaker:

“She has stepped up to the challenge and gone where she felt God was leading her, which meant stepping up into positions that I don’t think she would have ever guessed she would find herself in.”

From Steve Hildebrand of Sioux Falls, former Democratic campaign manager:

“When Kristi Noem wakes up every morning, she thinks about herself and her political future. She does not wake up every morning and think about what’s best for South Dakota.”

From Jon Schaff of Aberdeen, professor at Northern State University

“The thing that inoculates her from some of the criticism is that it’s really hard to out-South Dakota Kristi Noem .. and I don’t think that she’s lost that touch.”

From Reynold Nesiba of Sioux Falls, college professor and Democratic state senator

“South Dakotans inherently look after one another … {but} during COVID, it seemed like we were more interested in scoring political points. It could have been an opportunity for the governor to use her leadership to bring us together as a state; instead she used it to fan the divisiveness and push us further apart.”

Entering the political realm

Noem has said her political views were molded by the aftermath of losing her father, Ron Arnold, to a grain bin accident at the family’s Castlewood farm in 1994, when Kristi was 22 years old and expecting her first child with husband Bryon. Fresh challenges faced by the family as Kristi assumed greater responsibility in business affairs shaped her thinking on the extent to which the government should impact individual lives.

Noem’s small-business experience brought her in contact with Daschle, Democratic Senate Minority Leader at the time, who nominated her for a seat on the South Dakota Farm Service Agency state committee, to which she was appointed by then-President Bill Clinton.

“People wondered for years if maybe I switched to the Democrat Party to serve,” Noem wrote in her book. “Of course, I never did, and to his credit Senator Daschle never asked.”

Daschle did invite Noem in 2000 to his Black Hills Leader Retreat at Sylvan Lake Lodge for prospective legislative or local candidates, the overwhelming majority of whom were Democrats. Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, whom Noem would defeat in a momentous 2010 U.S. House race, attended Daschle’s retreat the year before Noem and credited the experience with inspiring her to run for statewide office rather than continuing a law career.

Steve Erpenbach, Daschle’s state director at the time, called Noem to gauge her interest in the retreat, which included visits to Mount Rushmore and Crazy Horse memorials and featured speeches by notable Democrats such as Harry Reid and Gabby Giffords during the event’s five-year run.

“She was interested but wanted to learn more,” said Erpenbach, who met with Noem at the Crossroads Hotel in Huron and received her commitment to attend, with the future governor vowing to use the experience strategically if nothing else.

Noem’s transition from intriguing prospect to active candidate came in 2006, when she ran for state House of Representatives as a Republican and finished first out of three candidates with 39% of the vote to win one of two District 6 seats.

By then she was the mother of three, helping to run the family’s farm operation, hunting lodge and Watertown restaurant, amassing perspectives that would define her as a lawmaker. She explored her niche within the Republican caucus, focusing on wind energy and agricultural property tax issues. Two years later, after easily winning re-election and being named Assistant House Majority Leader, the legislature was more of a proving ground, with ideological factions coming into focus.

Soon after Obama entered the White House in 2009, the fiscally conservative Tea Party movement emerged on the far right of the Republican Party, trumpeting tax reform and less government spending. Noem, who resisted joining political blocs, was derided as “establishment” after siding with Gov. Mike Rounds on the question of whether South Dakota should accept $1.3 billion in federal stimulus funds as part of the Recovery Act pushed through Congress without Republican support in the wake of the Great Recession.

“(Noem) voted in favor of taking all that money over the course of two years,” said Russell, who now serves as Fall River County State’s Attorney. “There were some of us who voted not to take the money, because of the strings attached to it at the time and the fact that South Dakota was faring better than a lot of other states. Voting to accept the money was a very establishment position to take.”

Any notion that Noem was a political wallflower was dispelled during a 2009 House committee hearing on a proposed constitutional amendment to allow expanded gambling in South Dakota. The amendment was viewed as a means of challenging a planned resort casino in Larchwood, Iowa, a project that opened as Grand Falls Casino two years later.

Sparks flew at the hearing when Noem suggested that Senate Democratic leader Scott Heidepriem had a conflict of interest because his law firm represented the Flandreau Santee Sioux Tribe in a federal lawsuit against the state over how many slot machines could be operated at the tribe’s Royal River Casino in Flandreau.

Heidepriem, who ran for governor in 2010 and lost to Daugaard, held a press conference to defend himself days later. He pointed out that another lawyer at the firm signed on to the tribal lawsuit after he brought the bill and that he wouldn’t have considered it a conflict even if he had known about it.

Reached by News Watch for this story, Heidepriem said he was “blindsided” by Noem’s allegations at the time and added that “I’m very proud of what I said and did.”

Democrats derided Noem’s challenge as reckless and politically motivated, while some Republican lawmakers and operatives, according to Venhuizen, took note that Noem was not afraid to enter the ring and throw a punch.

High-stakes battle with Herseth Sandlin

In the years since attending the Daschle retreat, Herseth Sandlin had lost the 2002 U.S. House race to former governor Bill Janklow and then captured the seat two years later after Janklow resigned in the wake of his manslaughter conviction for killing a motorcyclist in a car crash.

Herseth Sandlin, the granddaughter of former governor Ralph Herseth and daughter of longtime state legislator Lars Herseth, was a Georgetown Law School graduate and moderate “Blue Dog Democrat” with a bright future. But much of politics is about timing, and in 2010 she was viewed as vulnerable. The Democrats had taken over all three branches of the federal government in 2008, with a super-majority in the Senate, and Obama’s landmark healthcare reform package in the face of a still-struggling economy energized Republicans for the midterms.

Suzanne Veenis of Sioux Falls, a grassroots organizer whose “Women for Thune” efforts helped Thune outduel Daschle in the pivotal Senate election of 2004, saw an opportunity to tie Herseth Sandlin to Obama’s unpopularity in South Dakota, where his favorability hovered in the mid-30s percentile. The feeling was that the right candidate could be carried by political currents, rising above the reality that Herseth Sandlin, who declined an interview request for this story, had voted against Obamacare and was endorsed by the National Rifle Association.

“We felt it was time to find a Republican who could flip that seat and put the direction of the country in more of the way that South Dakota constituents wanted it to be,” said Veenis.

Since Thune didn’t have an opponent for re-election in 2010, his camp focused funding and energy on state legislative elections and defeating Herseth Sandlin, who could present a threat to Thune in the future. Veenis was tasked with persuading the 38-year-old Noem to run in a primary that already included Secretary of State Chris Nelson and state legislator Blake Curd, thinking she had a higher upside for a bare-knuckle general election.

Noem said she prayed on it with Bryon and their children, then ranging from 8 to 16 years old, and decided to take the leap, adding in her January 2010 announcement that South Dakotans “are best served when their representative has the same goals, experiences, and work ethic as they do.”

She won the primary with 42% of the vote and handled the heat in the general election, overcoming reports that she was ticketed 20 times for speeding over the previous two decades, with bench warrants issued twice for her arrest due to unpaid fines. When she attacked Herseth Sandlin for supporting Obama’s $800 billion stimulus package, the incumbent countered that Noem voted to accept her state’s share of the money as a legislator in Pierre.

Noem weathered the storm with retail campaigning heavy on rural advocacy, family values and Obama bashing, contrasting herself with an opponent she portrayed as banded to the bustle of Beltway politics. It was a tough sell, as Herseth grew up on a northeast South Dakota farm and had a young son with her husband, Max. But it revealed a blossoming of Noem’s political skill that went beyond physical presence or windows of opportunity to forge a homegrown connection. She needed every bit of it.

“Kristi resonated with voters,” said Veenis, who served as Noem’s statewide volunteer coordinator. “When we did our bus tour toward the November election, the crowds were huge, everyone was very excited, people were upbeat. She does very well with those campaign stops, whether it be restaurants or the Holiday Inn in Rapid City. She also had a strong message about less government, less regulation and advancing legislation to build people up rather than tear them down. It was the message that people in South Dakota wanted to hear.”

On election night, Noem and her family watched the results at the Ramada Inn in Sioux Falls, declaring victory shortly after midnight with 48% of the vote, with Herseth Sandlin at 46% and Independent Thomas Marking at 6%. Earlier in the night, Daugaard, who had served as lieutenant governor under Rounds for eight years, thanked supporters for his gubernatorial rout of Heidepriem by a margin of 62% to 38%.

It was part of a Republican wave across the country, with the GOP winning control of the U.S. House by gaining 63 seats and cutting into the Democratic edge in the Senate. They also flipped control of 20 state legislatures. There were plenty of success stories to go around, but Noem’s win signaled a turning point in South Dakota. Since her triumph in 2010, no Democratic candidate has managed to win statewide office.

“If you go back to when Kristi was in the state legislature, she was the one willing to call out Scott Heidepriem on some things when no one else was willing to,” said Venhuizen. “She was willing to take on Stephanie Herseth when a lot of others weren’t willing to, and I think that’s a string that carries through to the present, that she doesn’t give into pressure and she’s never afraid of a fight.”

Steering clear of Tea Party Caucus

Noem’s approach to her first term in Congress struck some on the far right of her party as more ambitious than combative. She was one of two House freshmen (out of a mammoth GOP class of 87 new members) elected liaison to House Speaker John Boehner and Majority Leader Eric Cantor in 2011, a route she took rather than team with Minnesota Rep. Michelle Bachman and the burgeoning Tea Party Caucus.

Noem also raised eyebrows by not landing a spot on the House Committee on Agriculture, breaking recent tradition for South Dakota representatives focused on protecting the state’s rural interests. She finally claimed a spot when a vacancy emerged in the summer of 2011.

“There was some stubbing of toes early on, but she proved herself to be a good soldier within the Republican Party in Congress – more establishment than rabble rouser,” said Schaff. “She was not one of these people, like Marjorie Taylor Greene or Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez, who clearly are in Congress to advance a personal agenda and are not really interested in pleasing leadership in any way shape or form. That was not Kristi Noem. She was in essence a good team player.”

While taking online classes at South Dakota State University to obtain her political science degree, which she completed in 2012, Noem railed against Obama’s health care policies and military intervention in Libya. She worked to roll back EPA regulations and include livestock disaster programs in the five-year Farm Bill, which passed in 2014.

To the extent that she walked a tightrope between GOP establishment concerns and the rumblings of the far right, Noem managed to keep her balance, easily winning re-election against Matt Varilek in 2012 and Corinna Robinson in 2014.

She dodged a primary challenge in 2012 from Rapid City resident Stephanie Strong, who drew headlines by highlighting Noem’s vote for a debt-ceiling increase and her decision to get “cozy” with Boehner rather than championing fiscal conservatism.

Strong’s candidacy was derailed by a lack of verified signatures, allowing Noem to stay in the middle and safely retain her seat, at least until a Manhattan real estate mogul and former reality TV star emerged on the political scene to turn everything on its ear.

Noem on Trump: ‘Not my candidate’

When Trump announced he was running for president and then began climbing GOP primary polls in 2015, Noem’s reaction was not that he was “the last line of defense against the far left,” as she claimed several years later. It was more about him being a threat to the mainstream Republican Party because some of his views on immigration and isolationism were “un-American.”

In declaring his candidacy in June 2015, Trump promised to build “a great, great wall” on the southern border and blamed Mexico for the flow of drugs, criminals and “rapists” into the country. In December 2015, after a mass shooting in San Bernardino, Calif., committed by extremists inspired by Islamic terrorist groups, Trump called for “a total and complete shutdown” of Muslims entering the United States “until our country’s representatives can figure out what is going on.”

Noem condemned the remarks and joined fellow Republican House member Mike Pompeo, who later became Trump’s Secretary of State, in endorsing Marco Rubio for the 2016 presidential nomination. In an interview with WNAX radio in late 2015, Noem said of Trump, “Well, he’s not my candidate,” and laughed before adding, “People came to this country for religious freedom, so I believe his comments were un-American, and I don’t agree with them.”

In a separate interview looking ahead to the Iowa Caucuses, Noem said of Trump’s sizable lead in the polls: “I look at the candidates who are running and think, ‘Who do I want in the room when we’re negotiating with Iran?’ It’s not going to be Donald Trump. His principles and values don’t align with mine, and his offensive nature wouldn’t serve us very well in the presidency.”

Her tone softened after Trump locked up the nomination, though she still referred to him as a “very flawed candidate” when announcing that she would vote for him over Hillary Clinton. Noem, who endorsed Trump when Ted Cruz suspended his campaign, didn’t pull that support after “Access Hollywood” tapes from 2005 leaked a month before the election and revealed Trump making vulgar comments about groping women. Thune and Daugaard were among Republicans who called for Trump to step down and let vice presidential nominee Mike Pence head the ticket.

“I appreciate apologies,” said Noem, who was running for re-election against Democrat Paula Hawks, a race she would win with 64% of the vote. “I love the Lord and I believe in redemption and that people can change over the years.”

When Trump defeated Clinton, he went from being a temporary headache for the Republican establishment to an unavoidable consequence of the party’s shifting tides amid economic anxiety and concern for the future. Noem certainly wasn’t the only politician who calibrated her treatment of Trump based on how it affected her prospects, but her turnabout, from calling him un-American to adopting his rhetoric and cultural grievances as part of her public persona, was among the most complete.

“Almost everyone was surprised that Trump won, maybe no one more than Trump himself,” said Schaff. “That probably tempered Noem’s (pre-election) support a bit. How much up front do you want to be supporting someone who is highly controversial and doesn’t look like he’s going to win? And then, bam, he wins. And because of that, there’s a strong Trump stamp on the Republican Party, and not being fully on the Trump train can bring large amounts of skepticism against you.”

Libertarian credentials in question

One of the transition points occurred when Noem visited the White House to visit President Trump and engaged in playful banter about her state’s most prominent landmark, Mount Rushmore.

“He said, ‘Kristi, come on over here. Shake my hand,’” Noem recalled in her book. “I shook his hand, and I said, ‘Mr. President, you should come to South Dakota sometime. We have Mount Rushmore.’ And he goes, ‘Do you know it’s my dream to have my face on Mount Rushmore?’”

Noem reacted as if the president was playing a joke. “I started laughing,” she said. “He wasn’t laughing, so he was totally serious.”

She posted photos of herself in 2017 with Ivanka Trump, the president’s daughter and one of his senior advisors, engaging in informal policy discussions. “When you’re talking to her, I think there’s a chance that it will end up in a conversation that she’ll have with the president and people in the White House as well,” Noem told the Argus Leader at the time.

Serving on a House conference committee, Noem helped negotiate passage of a $1.5 trillion tax cut that served as the Trump administration’s first legislative victory. She used the story of her father’s tragic death – and the financial fallout faced by her family – to illustrate the need for estate tax reform because of the undue burden on those left behind.

In an earlier speech on the House floor, Noem related that soon after her father’s death “we got a bill in the mail from the IRS that said we owed them money because we had a tragedy that happened to our family.” Amid the 2017 debate over what she termed “the death tax,” questions swirled around that claim, including the fact that her mother should have been able to assume the family assets through a marital deduction without being subject to estate tax. Noem countered that her father never signed his will, complicating the inheritance.

Tax experts clarified that estate taxes can be deferred for up to five years, with flexible installment plans offered, and typically aren’t assessed until a tax return is filed, casting doubt on Noem’s cautionary tale. Documents also showed that Noem’s mother, Corrine, received $1.1 million from her husband’s life insurance policies, a figure significantly larger than the estate taxes owed.

“For a decade after a tragic farming accident took my dad’s life, the Death Tax impacted nearly every decision our family made,” Noem said in a statement at the time. “To allege anything else is fake news.”

It wasn’t the first time that the finances of her family’s Racota Valley Ranch drew public scrutiny. The 9,700-acre property received nearly $4.3 million in U.S. Department of Agriculture subsidy payments from 1995-2020, according to the Environmental Working Group database, causing some to question Noem’s much-espoused ideology of freedom from government involvement.

“It’s hard to be libertarian when you’re taking federal money with both hands,” said Larry Pressler, who represented South Dakota in the U.S. Senate and House as a Republican and later ran unsuccessfully as an Independent. “I know (Noem’s) family and they’re wonderful people, but they’ve taken every kind of farm aid and subsidy. We can’t go around preaching about libertarianism if we’re taking federal money for farms, infrastructure, education and so forth. South Dakota runs on federal aid. We just don’t like to admit it.”

Rough-and-tumble primary for governor

By the spring of 2016, there was already talk of a hotly contested Republican primary for governor when Dennis Daugaard’s second term would end in 2018. Attorney General Jackley was expecting a sturdy challenge from state legislator and legacy candidate Mark Mickelson, whose father and grandfather both served as governor.

Republican lawmaker Lee Schoenbeck mentioned Noem’s potential candidacy as the “800-pouind gorilla in the room,” and she announced she was running for governor six days after her 2016 re-election to the House, beating a deadline to transfer funds left from the U.S. House campaign into a state account for governor. The decision was made after she met with Mickelson and learned that he would not be running.

That left a primary with Noem facing Jackley, a self-described “consistent conservative” who campaigned on traditional party priorities, noting that he signed onto cases as attorney general defending religious liberty and restricting access to abortion while defending “law and order” at home with prosecutions stemming from the state’s EB-5 and Gear Up scandals.

Noem’s camp highlighted her farm and ranch background while dismissing Jackley as a “government lawyer” presiding as attorney general over a state with rising cases of violent crime and drug arrests, which Jackley countered by questioning Congress’ efforts to stop narcotics from being smuggled across the southern border.

“She was a very strong and worthy opponent,” Jackley told News Watch. “I’ve always said that whether it was on a college track (as an athlete) or in a courtroom, I run my race and try my case. In other words, I was running for governor because of what I felt I could do for South Dakota, the vision that we had, the leadership team we had. I was running irrespective of whoever else was running.”

Noem had considered and ultimately declined a primary run against Rounds in 2014 for the open Senate seat vacated by retiring three-term Democrat Tim Johnson. But now the timing felt right. Her stint in Washington had been marked by frequent weekend trips to Castlewood, S.D., to see her family, with the natural inclinations of a wife and mother pushing her toward another bold career gambit, this time in the direction of home.

“It was another example of her being willing to take a risk,” said Schaff. “You’re talking about a sitting U.S. Representative who could have cake-walked to re-election for the rest of her career deciding to take a plunge into a competitive gubernatorial race.”

Whereas in earlier campaigns Noem’s gender had been of secondary consideration, this time she put it out front, trumpeting the possibility of South Dakota electing its first female governor. She also knew from experience the right time to sharpen her elbows. Late in the race, with polls showing a tight margin, Noem’s campaign launched TV ads hitting Jackley for his handling of a case involving a former Department of Criminal Investigation agent who received a $1.5 million state settlement on the heels of a discrimination and retaliation lawsuit.

Jackley’s performance as South Dakota’s top prosecutor had been his platform – he had successfully argued a U.S. Supreme Court case that allowed South Dakota to tax purchases made from online retailers – but he was forced to defend himself against charges of malfeasance at the most crucial stage of the race. His efforts fell short as Noem surged with 56% of the vote to seal the nomination.

Noem wrote in her book that the 2018 election was “like a knife fight in a ditch,” to which Jackley responds: “I hope I was more professional than that. If I wasn’t, I apologize to the people of South Dakota.”

Close win for state’s first female governor

The excitement surrounding Noem’s primary triumph was tempered by her inability to pull away from Democratic challenger Billie Sutton in the general election. Sutton, a four-term state senator and former bronc rider paralyzed from the waist down from a rodeo injury at age 23, had a ranch background of his own, with his ubiquitous cowboy hat accentuating his West River roots.

Jackley, still stinging from primary mudslinging, didn’t endorse Noem until late October of 2018, a few weeks after the non-partisan Cook Political Report shifted the race from “Likely Republican” to “Toss-up,” with election analysts citing indications that Noem’s team was taking the race for granted.

Cracks in Noem’s “rising star” profile started to show. Statewide polling showed she trailed Sutton 51% to 40% with women and that her overall unfavorable rating in South Dakota stood at 37%, compared to 33% for Trump. Efforts to portray Sutton as a raging liberal, a tried-and-true tactic for Republicans in statewide races, largely fell flat due to his support for abortion restrictions and gun rights.

“Kristi Noem is a hyper-aggressive, largely negative campaigner,” Hildebrand said about the race. “Her message to voters was, ‘I stood with Trump, I’m an ideological Republican and Billie Sutton is the devil.’”

On election night, her winning margin of 51% to 48% was conspicuous in a state where Republican candidates had won 10 consecutive gubernatorial races by an average of 23 points. It was not the sort of mandate Noem had sought for her first executive role, with a steep learning curve ahead.

Noem has blamed her administration’s early struggles on extreme weather, noting that federal disasters were declared in 58 of 66 counties and on three reservations in 2019 due to tornadoes and flooding. Others point to Noem’s inexperience and staffing decisions to explain misfires such as the much-ridiculed “Meth. We’re on It” ad campaign, an ill-fated crusade against hemp legislation and legal setbacks the state incurred for cracking down on potential Keystone XL pipeline protests, which led the Oglala Sioux Tribal Council to temporarily ban her from the Pine Ridge Reservation.

By March of 2020, a little over a year after being inaugurated, Noem was on her third chief of staff and her approval rating stood at 43%, daunting prospects for a governor about to face the most significant public health crisis in state history.

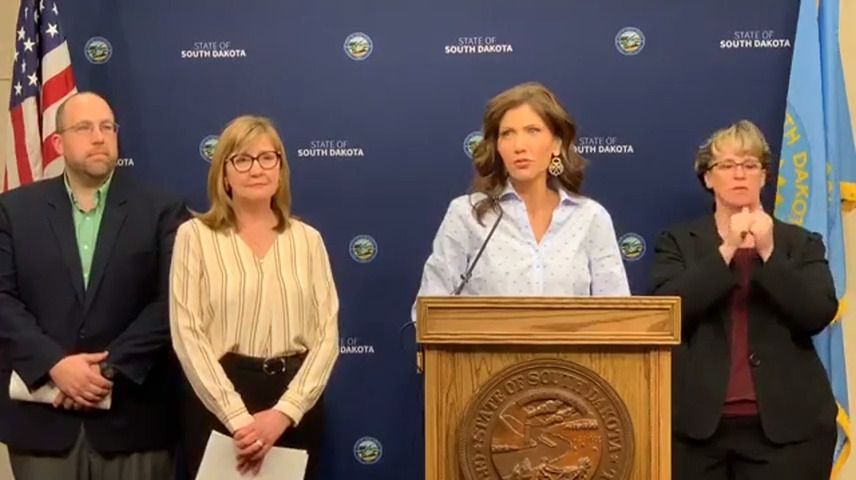

South Dakota in national spotlight

Ian Fury recalls driving across the Midwest in the early stages of the COVID pandemic to start his new job as Noem’s communications director. He was recruited by senior advisor Maggie Seidel, a former Koch Institute media strategist who came to Pierre in November 2019 to shore up the governor’s sagging policy and public relations efforts.

Fury, who had spearheaded communications for Ohio U.S. Rep. Jim Jordan, made the trip from Ohio to Pierre the first week of April 2020, as the contrast in pandemic response between various states and governors took on political tones.

“There were flashing billboards in Ohio telling people to stay home, that it wasn’t safe to go outside, and signs in Illinois telling people only to go out for necessary errands,” said Fury. “Then I cross the border into South Dakota and get to Sioux Falls and there’s a flashing billboard that says, ‘Facts not Fear,’ encouraging people to visit the state website. It wasn’t downplaying COVID. It wasn’t saying to ignore COVID. It was saying to get the facts, and it was the only state where I had seen a message that wasn’t explicitly fear-mongering.”

Fury helped turn it into a political creed that would elevate the governor’s profile, and he felt uniquely suited to do so. He grew up in Houston with parents firmly entrenched conservative politics. His father, Mark, was chairman of the Committee for Texas Right to Life, where his mom, Jill, served as a volunteer. Mark also served on the board of the Texas Republican Party and Jill was a precinct captain.

Fury attended high school in Nebraska and then set off for Hillsdale College in south-central Michigan, a conservative liberal arts institution that gained national influence in the debate over the politicization of history and civics curriculum in public schools. He graduated with a degree in political economy in 2015 and started working for Sam Brownback, a Kansas senator at the time, followed by a stint with the Koch brothers-funded Americans for Prosperity before getting the job with Jordan, one of Trump’s top defenders during the first impeachment process.

By the time he reached Pierre, South Dakota coronavirus cases were surging, with the Smithfield Foods pork processing plant in Sioux Falls the No. 1 hot spot in the country. After shutting down schools in March and writing a letter to Smithfield (along with Sioux Falls Mayor Paul TenHaken) asking that the plant suspend operations for 14 days, Noem reversed her stance on mitigation measures around the same time Trump called on states to “open up this incredible country” by Easter, which fell on April 12.

Noem rebuffed calls for statewide shutdowns and mask mandates, citing “science, facts, and data,” and coordinated with the White House on a state clinical trial for hydroxychloroquine, a malaria drug Trump touted as treatment for hospitalized COVID patients that the FDA later said has “not been shown to be safe and effective for treating or preventing COVID-19.”

These actions led to lavish praise from conservative media outlets and castigation from left-leaning pundits such as MSNBC anchor Rachel Maddow, who challenged Noem’s “crazy denialism” to her nightly audience of 3 million viewers. The fact that more than 3,000 South Dakotans suffered deaths related to COVID-19 is not lost on Noem (the state ranks 11th in most deaths per 100,000 residents, according to CDC data), but in her book she defends the state’s response to the pandemic as “our finest hour.”

“It’s less that she found her voice and more that she found her moment,” said Fury. “And I would point out that the national prominence that came with it wasn’t driven by seeking clout. When the Smithfield outbreak happened, Rachel Maddow talked about Gov. Noem on the air five nights in a row. The Washington Post and New York Times were writing about South Dakota, and she was defending her position.”

Politics during a pandemic

The irony of Noem’s stance was noted by South Dakota’s far-right legislators, who recalled her April 6 “stay at home” executive order directed toward Minnehaha/Lincoln County residents 65 and older or with an underlying medical condition. Noem’s office also brought COVID-related bills to the floor of the legislature during a hectic March 30 veto day session, including one that would have given her state health secretary the power to shut down or restrict public or private businesses, parks, schools and other locations that “promote public gathering” if they didn’t follow CDC guidelines during the health emergency.

“After the House killed those bills, I saw reports that she had gone to Florida and badmouthed Ron DeSantis for shutting down beaches and things,” said Russell, referencing Florida’s governor, who is also considered a national GOP presidential hopeful.

Russell also noted: “She saw how the tea leaves were trending and in a calculating change of heart, she took on that persona of not shutting anything down and criticizing other governors for doing so. Technically, the South Dakota House kept the state open.”

Noem shrugged off such criticism and pushed forward, engaging in a legal standoff with tribal officials over their use of roadside checkpoints to try to control the spread of the coronavirus on reservations. She placed no restrictions on the Sturgis Motorcycle Rally, which brought nearly 500,000 visitors to the Black Hills in August of 2020 and contributed to “widespread transmission” of COVID-19, according to CDC researchers.

“South Dakotans inherently look after one another,” said Reynold Nesiba, a Democratic state senator from Sioux Falls. “We pride ourselves on helping each other, whether it’s bringing in the harvest or taking care of someone who is unwell. During COVID, it seemed like we were more interested in scoring political points. It could have been an opportunity for the governor to use her leadership to bring us together as a state; instead she used it to fan the divisiveness and push us further apart.”

The strategy brought her closer to Trump, who announced plans for Fourth of July fireworks at Mount Rushmore with no social distancing, adhering to Noem’s “personal responsibility” doctrine. As for National Park Service concerns about embers from fireworks sparking wildfires, or Native American activists outraged at Trump’s celebration on sacred land during a summer of racial reckoning, none of it prevented the patriotism-themed display – with imagery later used in election-year ads – from moving forward.

“She had basically decided that she was going to go all in and be an open Trump supporter,” said Schaff. “I think that changed things for her and her thoughts on the future. She got the whiff of presidential aspirations, and once you get a hold of that, I suspect it’s very hard to let go.”

Lewandowski makes his mark

Early fanfare surrounding Trump’s Mount Rushmore visit on July 3, 2020, centered on Ellsworth Air Force Base, where the president and his contingent touched down on Air Force One.

Trump and First Lady Melania Trump were greeted at the bottom of the steps by Noem and Thune, with no handshakes and six feet of separation, in accordance with CDC guidelines. A few moments later, Lewandowski descended the stairs and greeted the governor with a handshake and kissed her on the cheek before retreating to the background.

The gesture did not nothing to tamp down speculation about Lewandowski’s growing influence on Noem’s political affairs, a relationship that coincided with her rise in national stature during the COVID pandemic.

“Corey writes a lot of her stuff,” said Hildebrand. “I think she saw that she could have a significant fundraising advantage nationally, especially at the small donor level, if that was the language she spoke. And he helped her get there.”

Lewandowski is a longtime political operative who mounted an unsuccessful campaign for state legislature while attending college at the University of Massachusetts-Lowell, after which he decided to boost candidates, not be one. At the age of 25, he ran a re-election effort for Ohio Republican Congressman Bob Ney and then worked as deputy chief of staff, making headlines in 1999 when he was arrested for carrying a handgun and several rounds of ammunition into the Longworth House Office Building on Capitol Hill.

“He was returning to Ohio with his laundry,” Ney explained at the time. “He forgot the gun was in there.”

His penchant for going rogue was sealed when he ran the U.S. Senate campaign of New Hampshire Republican party outsider Bob Smith in 2002, a failed primary effort that saw Lewandowski take heat for indirectly tying rival candidate John E. Sununu to terrorism because he accepted support from an Arab-American anti-discrimination group in the aftermath of 9/11. Sununu, of Lebanese descent, is the son of former New Hampshire governor John H. Sununu, who served as chief of staff to George H.W. Bush.

“I would use the term ‘he’s dead to us’ to explain the relationship between Lewandowski and the Sununu family,” said Andy Smith, a political science professor who runs the University of New Hampshire’s Survey Center. “That was not a good move for Corey.”

Lewandowski worked for Americans for Prosperity before being hired as Trump’s campaign manager in late 2014. Controversy erupted again when he was accused of yanking the arm of Breitbart News reporter Michelle Fields at a Trump event in Florida in March 2015. Lewandowski was fired as campaign manager in June 2016 after clashing with campaign chairman Paul Manafort, but he has maintained ties to his former boss and used that relationship to secure consulting and lobbying jobs, with MAGA-style populism a common thread.

“Corey’s a good ground-game campaign person and organizer – I don’t want to sell him short,” said Smith, a veteran of the New Hampshire political scene. “But his biggest connection obviously is Trump, and he’s using those connections and maybe the impression that if he’s working with somebody, that person gets Trump’s tacit endorsement. He’s been capitalizing on that for a while.”

Noem’s faith in Lewandowski was tested on the night of Sept. 26, 2021, when he was accused of sexual harassment and threatening behavior by Trump donor Trashelle Odom at a Las Vegas charity event also attended by Noem.

“I was intimidated and frightened and fearful for my safety and that of my family members,” Odom, the wife of an Idaho construction company executive, said in a statement to police. She claimed that Lewandowski harassed her repeatedly while seated next to her at the event, touched her leg and buttocks, bragged about his violent past and became angry when she rejected his advances.

“It was apparent that my reactions to Lewandowski’s stories, threats and aggressive sexual advances were not normal for Lewandowski as he ultimately threw his drink on me, hitting my dress, shoe and foot,” Odom said in the statement. She added that at one point in the evening, “I saw Gov. Noem and intended on introducing her to my sister and stepson, who both had joined me on the trip. Gov. Noem told me that she had texted Corey to stop touching me. This was confusing for my sister and stepson.”

A Trump spokesman responded to the allegations by saying that Lewandowski, who has been married since 2005 and has four kids, “will no longer be associated with Trump World.” Noem’s office said she was also cutting ties with Lewandowski, with Fury insisting that Lewandowski was merely a volunteer and “will not be advising the Governor in regard to the campaign or official office.”

Lewandowski was ultimately charged with misdemeanor battery for the Las Vegas incident, but according to a deal with prosecutors, the charges will be dismissed if Lewandowski completes eight hours of impulse control counseling, serves 50 hours of community service and stays out of trouble for a year.

By the time he cut that deal in September 2022, he had worked his way back into Noem’s political circle. She appeared with Lewandoski at an August 2022 fundraiser for Massachusetts GOP gubernatorial nominee Geoff Diehl, where Noem and Diehl strolled the north end of Boston, eating pizza and hob-knobbing with merchants.

The Trump-endorsed Diehl, who has questioned the legitimacy of the 2020 presidential election, said that he and Noem “very much share the same values” when asked about her extreme positions on abortion. Lewandowski also worked for U.S. Senate candidate Jane Timkin of Ohio, who was endorsed by Noem in August of 2021. Timkin spoke of “widespread fraud and irregularities” in the 2020 election, without citing evidence, and praised Lewandowski’s experience in high-level campaigns without mentioning the allegations in Las Vegas.

“People will overlook a lot of sins if they think Corey can help them get elected,” said Smith, though Timkin failed to land Trump’s endorsement and finished fifth in the Ohio primary, while Diehl trails Democratic gubernatorial candidate Maura Healey by as many as 24 points in recent Massachusetts polls.

Asked about Noem’s Trump-inspired political transformation, Smith added: “It’s the mood of the country and the mood of the Republican Party. If the party shifts, you have to go where the party is and try to run in front of the parade. A skillful politician is the one who can do that and not make it look too opportunistic.”

Battling inside and outside the GOP

One problem with being a “political chameleon,” Noem’s detractors say, is that your true colors become harder to find. But a politician’s first instinct can be revealing.

When the Republican-dominated South Dakota Legislature pushed through a transgender athlete bill in 2021 that would have banned trans females from competing in sports programs in South Dakota, Noem initially voiced support but then issued a style-and-form veto, expressing concern about college sports being included and financial repercussions if the NCAA boycotted events.

“The NCAA is a private association,” Noem said at a press conference following her decision not to sign the bill. “That means they can do what they want to do. And even though I fundamentally disagree with them when it comes to this issue, if South Dakota passes a law that’s against their policy, they will likely take punitive action against us.”

Though Noem tried to rally support for a “Defend Title IX Now!” coalition, she was assailed by hard-core conservatives as a “sellout” who “caved” to corporate interests. In a contentious interview on Fox News, host Tucker Carlson asked her: “Why not just say, ‘Bring it on, NCAA. I’m a national figure. Go ahead and try and exclude us. I will fight you in the court of public opinion and defend principle.’ Why not just do that?”

The first-term governor took a more aggressive position for the 2022 legislative session. Her office put forth a retooled bill, removing logistical challenges for schools and adding a clause to provide legal representation from the attorney general for various entities in case they were sued. But the swiftness with which the reactionary right had turned on her was instructive.

“She went on Tucker Carlson and kind of got beat up,” said Schaff. “He made her look bad, which is hard to do. He made her look weak and dissembling, so I think she came to the realization that ‘this could hurt me; I won’t veto that thing a second time.’ And she didn’t.”

Close governor’s race awaits

In her videotaped message at the Media Research Center event in Washington D.C., Noem framed her hands-off approach to the pandemic as a nod to individual liberties, portraying South Dakota’s wide-open spaces as a red-state haven where freedom rings.

She justifies her national travel – made possible by payments and in-kind contributions through her Victory Fund PAC – as part of her role as state ambassador, extolling the virtues of South Dakota to boost tourism. Noem’s administration used $5 million in coronavirus relief funds in 2020 for the same purpose, running an ad campaign featuring the governor and state landmarks such as Mount Rushmore and the Badlands.

“We invited freedom-loving Americans to come to South Dakota,” Noem told the Media Research Center audience, “and they came to our state in record numbers.”

South Dakota Department of Tourism Secretary Jim Hagen said the state is on track to “either match or surpass the $4.4 billion in visitor spending we experienced in 2021,” though National Park visitation is slightly down, and hotel room nights declined over the summer “with astronomical gas prices and crippling inflation causing American families to cancel their trips,” according to Hagen.

Noem’s travel schedule is also targeted to boost her politically – with appearances and digital ads in key electoral states – but it’s not clear how much her time away from Pierre hurts her at home.

“There are lots of people who say she shouldn’t have ambition, but my perspective would be that you hope everybody has a little bit of ambition,” said Card, the USD political science professor. “Her opponents would say it’s a question of whether she’s speaking to us or speaking to (out-of-state audiences).”

South Dakota voters have traditionally been wary of officeholders who place national priorities ahead of state issues. Thune’s attacks on Daschle in 2004 focused on the Senate Majority Leader and his wife being entrenched in Washington, including a video clip of Daschle saying, “I’m a D.C. resident,” though Daschle’s campaign offered evidence that he was speaking in jest.

“I would advise South Dakota politicians to pay attention to South Dakota issues,” said Pressler, who blamed his own 1996 Senate loss to Democrat Tim Johnson on inattention to local concerns. “Be careful not to get too far off the reservation, so to speak. That would be my advice to all South Dakota politicians who want to be elected or re-elected.”

Others point to the fact that Daschle was embroiled in a high-stakes race in a ruby-red state against a rising Republican star in 2004, while Noem has history and money on her side against an opponent running his first statewide campaign in a tough election year for Democrats.

“Whatever Jamie Smith is, he isn’t John Thune,” said Schaff, shrugging off the Thune/Daschle comparison. “He’s not a Republican running in a Republican state in a Republican year with A-level political talent, which was Thune in 2004. Jamie Smith isn’t that. You might say that Noem has popularity to burn, and if she’s burned a little bit because she has cultivated a bit of a national profile, I doubt it costs her re-election.”

Also looming is an ethics investigation involving Noem’s alleged interference in a state agency’s evaluation of her daughter’s application for a real estate appraiser license, which involved a state employee receiving a $200,000 settlement after filing a wrongful termination suit.

The state’s Government Accountability Board determined there was evidence Noem acted improperly but refused to publicly disclose the “appropriate action” it took after making that finding, ending the matter in the public eye but allowing questions about the process to remain.

“The longer the issue stays on people’s minds and they talk about it, the worse off it is for her,” said Card. “Part of that is the lack of transparency that was written into the statutes, whether things are handled in public or private. If there’s a private reprimand, no one will know, and that will feed into our South Dakota suspicion that somebody’s getting a better deal.”

Re-election bids are a referendum on the incumbent, which is especially true in this case. A vote for Noem is not just for a second term as governor but a tacit endorsement of her political prospects, which may or may not take her away from gubernatorial duties. A loss would be a staggering blow to her political ascendancy and MAGA-fueled momentum, not to mention one of the most consequential election results in South Dakota history.

“I don’t think this election is about Kristi Noem’s career,” said Nesiba. “This election is about the future of South Dakota, and South Dakotans see Jamie Smith as more in line with their values and their concerns than they do with the current governor. That’s why she’s going to lose, and she doesn’t seem to be aware that that’s about to happen.”

It could be that even Noem’s most vocal critics don’t know what makes her tick. Maybe she’s still figuring it out herself, veering from star-spangled freedom fighter to calculating climber, sailing on political winds. One thing in Noem’s favor, said Schaff, is her understanding of her home state, which gives her the courage of her convictions, however flexible they might be.

“The thing that inoculates her from some of the criticism is that it’s really hard to out-South Dakota Kristi Noem,” he said. “And I don’t think that she’s lost that touch.”