MILLER, S.D. – The expansion of concentrated animal feeding operations, or CAFOs, in South Dakota is without a doubt one of the most controversial topics in agriculture.

CAFOs are large livestock farms that generally house 1,000 or more animals in a confined, indoor space at any one time.

Supporters say the CAFOs are mainly well-run, efficient operations typically owned by families that raise animals humanely and manage wastes in line with state regulations.

Opponents, meanwhile, decry what they see as mistreatment of animals and are concerned over potential human health risks and the potential for environmental damage.

South Dakota is now home to 452 CAFOs that are legally allowed to house about 9.6 million animals in all, mainly cattle, hogs, chickens and turkeys.

As part of its special report on CAFOs, South Dakota News Watch visited three CAFOs in South Dakota to get an up-close look at the operations and the operators. Here is a report on those visits.

Hog farmer tries to set an industry example

Matt Moeller grew up on a small farm in Hand County, but as a young adult he felt underutilized on the family farm and decided to seek opportunities in the big city of Sioux Falls.

He spent a couple of years welding fire trucks and flatbed trailers, but the call to agriculture was strong and he spent his final three years in Sioux Falls working in a dairy.

One day, Moeller’s uncle told him that the pork-production company Murphy Brown, now a subsidiary of Chinese-owned Smithfield Foods, was looking for people in South Dakota who might be interested in raising hogs.

In his late 20s at the time, Moeller jumped at the chance, and in 1998, he and his uncle built three hog barns on a small slice of land not far from his childhood home.

Now, more than 20 years on, Moeller owns the operation outright and has a state CAFO permit that allows him and his wife, Karen, to house 7,700 hogs at any one time.

“You know that saying, ‘You can take the boy out of the farm but not the farm out of the boy, or something like that?” said Moeller, 47. “I just really wanted to come back to farming.”

By all accounts, Moeller has an outstanding reputation in the agricultural industry — and even among opponents of CAFOs — as a good person and a good operator.

His farm consists of two sites that total about 60 acres just east of St. Lawrence on U.S. 14 in Hand County.

His modest home sits directly between his two sets of hog barns — three 50-foot by 200-foot barns that each house 1,100 hogs at a time, and two 50-foot by 400-foot barns that each house 2,200 hogs at a time. The larger barns, added in 2008, are each about half the size of a football field.

A 1.5-million-gallon metal tank that rises 20 feet high holds the manure collected daily from the barns and lies within sight of his home.

The entrance to his farm and the barns is remarkably clean for an operation that raises thousands of pigs each year. In a five-month process, piglets weighing 15 to 18 pounds are fed and raised to a finishing weight of 280 to 300 pounds each.

Cleanliness helps reduce mortality; any visitor allowed in must don a blue protective suit and footies.

The pigs are segregated into groups of about 65 in pens within the barn that are 20 feet by 22 feet, each with about 12 feet of solid concrete floor, and 10 feet of concrete floor with slats that allow wastes to fall below. Moeller said the pigs try hard to keep themselves clean, spending time on the sawdust-covered hard concrete when eating and milling about and moving to the slats only when they need to expel wastes.

Underneath the barns lies a shallow, foot-deep concrete waste-collection area that is scraped by an automatic system each day to force wastes through a pipe and into the slurry tank. The worst job on the farm is when the scraper system needs maintenance and must be tended to by hand, Moeller said.

Moeller works closely with Smithfield, which provides him with the hogs and technical assistance. He is mainly responsible for feeding and caring for the pigs and properly handling wastes. Twice a year, typically in spring and fall, depending on the weather, Moeller engages a pumping and piping system that allows him to spread the liquid manure onto neighboring farm fields as fertilizer.

Upon reaching finishing weight, the hogs Moeller grows are picked up and transported by Smithfield to slaughterhouses in Sioux Falls or Crete, Nebraska.

In 2018, Moeller raised his hogs as RWA, or raised without antibiotics, a more expensive process that enabled pork from his farm to serve a growing consumer base seeking foods raised with fewer additives. Mortality is higher during the RWA process, he said, and it takes more work because when an antibiotic-free animal gets sick, it requires medical treatment and must be segregated and sold separately in order to maintain the integrity of the larger RWA herd.

This year, however, Moeller said consumer demand shifted back to a desire for less-expensive pork, so he returned to production of “commodity” pigs that can be provided with antibiotic-infused feed that keeps more of them alive but cannot carry special labeling.

“Anytime it takes more time and mortality is higher, it costs more money, and the consumer has to pay that,” he said.

His animals, Moeller said, are kept in a climate-controlled environment where the temperature is always 65 degrees, even when it is below zero or near 100 degrees outside.

Moeller said he has a great relationship with his neighbors, mostly farmers themselves, whom he helps with chores on occasion. He said he alerts them when he is about to spread manure — the smelliest time of the year — and he once put off spreading so a neighbor could have an outdoor graduation party.

Moeller said the odors from his operation are less intense than some other CAFOs because his shallow-pit operation requires daily cleaning and does not hold manure beneath the animals for up to a year, like other CAFOs. The shallow pit also allows him to avoid using fans that blow odors and gasses out into the air around deep-pit CAFOs.

Still, depending on the day, the odors from Moeller’s farm can be smelled readily upon approach to his operation on U.S. 14 and may linger on the clothes of a visitor who spends some time at the farm.

Raising hogs has provided a good living, said Moeller, who takes trips with his wife in their camper and enjoys rodeo and racing cars. He has one full-time farmhand and sometimes also employs part-timers.

“The hardest part is just washing the barns and getting them ready for the little pigs, and you have to be here every day and make sure they have feed and water,” he said. “It’s like any job. If you enjoy it, it’s not hard work, and if you don’t, it’s miserable.”

Moeller is aware of the opposition to existing large livestock operations and the expansion of CAFOs in South Dakota, but he said opponents are often misinformed about local ownership, health risks, manure management and especially animal treatment.

“These pigs, they got it made,” he said. “They have all the feed they want in front of them, they have all the water they need, and they’re at 65 degrees all day,” Moeller said. “It’s a felony to abuse your animals, and pork producers are in favor of those laws.”

Moeller said increased economies of scale have occurred in many industries, including agriculture.

“I don’t know any farm anymore run by a husband and wife with just a couple cows and chickens and hogs,” he said.

His true measure of success, he said, is operating a farm that he and his wife can be proud of. That starts with keeping the farm and barns tidy and ends with forging good relationships with neighbors and treating animals humanely.

“It goes a long way when somebody drives up and sees your place clean and mowed as opposed to junk all over the place and weeds growing over,” Moeller said. “I take a lot of pride in my facilities and my farm and in trying to do the right thing.”

Part-time cattleman upholds family history

Brian Alderson and a visitor stand on a wooden platform 10 feet above the floor of his cattle barn as about 600 half-ton animals mill about below.

About 15 minutes into a conversation, Alderson asks, “You tell me, does it stink in here?”

Surprisingly, despite the fact that a few animals had defecated and flatulated, and that the platform hovers over a 1.2-million-gallon underground manure pit, the odors are minimal.

Alderson insists his deep-pit cattle barn that sits north of Highway 42 about 12 miles west of Sioux Falls has led to a major improvement on the environment and on the lives of his neighbors when compared to the open-air feedlot he used to operate.

“While there is a faint odor in here, I only had 200 steers outside and it smelled way worse than in here, especially when it rained and the odor of ammonia came up,” Alderson said. “It’s a night-and-day difference.”

Alderson, 37, is a former standout football lineman who brushed up against an NFL career and who was enshrined in 2019 into the University of South Dakota Coyote Sports Hall of Fame.

Alderson is now a part-time cattleman who has a full-time job as a cropland insurance adjuster. He and his wife, Erin, have sons ages 5 and 3.

His lone 14,400-square-foot barn can produce about 750 Holstein cattle each year, and is a fairly low-intensity operation in terms of manpower. The cattle barn allows him to keep his hand in farming and maintain a family tradition on his land that stretches back to 1876.

“I can do this in two or three hours a day, about 20 hours a week,” Alderson said. “I can hang out with my kids and do it 300 yards from my home. My boys play down here and they like hanging out with their dad.”

Alderson obtained a conditional-use permit from Minnehaha County in 2017 that allows him to raise up to 950 head of cattle. Though his operation is under the 1,000 animal threshold that would trigger the need for a state concentrated animal feeding operation permit, Alderson operates his farm much like CAFOs that house a few hundred or even thousands more cattle.

He has an arrangement with JBS Beef, a Brazilian-owned firm that provides meat to Walmart, among other sellers.

About every nine months, Alderson receives a shipment of roughly 600 cattle that weigh about 500 to 600 pounds each; they are held within four separate pens within the larger barn.

He feeds and cares for them until they reach their roughly 1,200-pound finishing weight.

During each cycle, Alderson said he spends about $700 in feed on each animal, generating roughly a half-million-dollar impact on the local feed market each year.

As the animals grow, their wastes fall into the underground pit, which is 12 feet deep and has a 12-inch concrete liner with a double layer of rebar. Additives are mixed into the pit wastes to break down bacteria and reduce odors and gasses, Alderson said.

Typically once a year — like all CAFO operators — Alderson pumps the liquid wastes from the pit onto area farm fields as fertilizer. He said that 36-hour period is the one time per year the smells at his farm become intense. Alderson spent about $20,000 in engineering costs to make sure his barn was efficient and safe.

The operation allows him to control the flow of wastes, and accompanying odors, far better than when his cattle were allowed to stroll around and do their business in pastures, he said.

Alderson bristles when discussing the opposition that invariably arises when any new CAFO is proposed in South Dakota. He, like other livestock farmers, said many opponents are ill-informed about farming in general and especially about how animals are treated and wastes are managed at large livestock operations. About 50 people showed up to his conditional-use hearing and he eventually endured six appeals to his permit.

“There was a lot of fear about what this was going to turn into; they saw cattle and they said, ‘That doesn’t look very good,’” he said. “But now I don’t think they notice it. Their day-to-day life hasn’t been affected at all, and in fact, I think it has improved.”

Alderson said South Dakota producers have increasingly specialized in one type of animal or crop in order to improve efficiency and profitability. Ultimately, the changes in agriculture are being driven by consumers who buy the meat and other goods farmers produce — and much of that demand is pushed a desire for low prices.

“If all you want to see is grass and a few cattle out your door when you look out, the next time you go to a barbecue, instead of picking up a six-pack of beer and a pound of hamburger, go ahead and spend that whole 12 bucks on the pound of hamburger,” Alderson said, noting that free-range or organic foods often cost significantly more. “It’s demand, and you tell us what you want us to do when you go to the grocery store.”

A colony of families and farms

The Oaklane Colony in Hanson County is a fully functioning town, with a school, housing and a handful of varied farm operations.

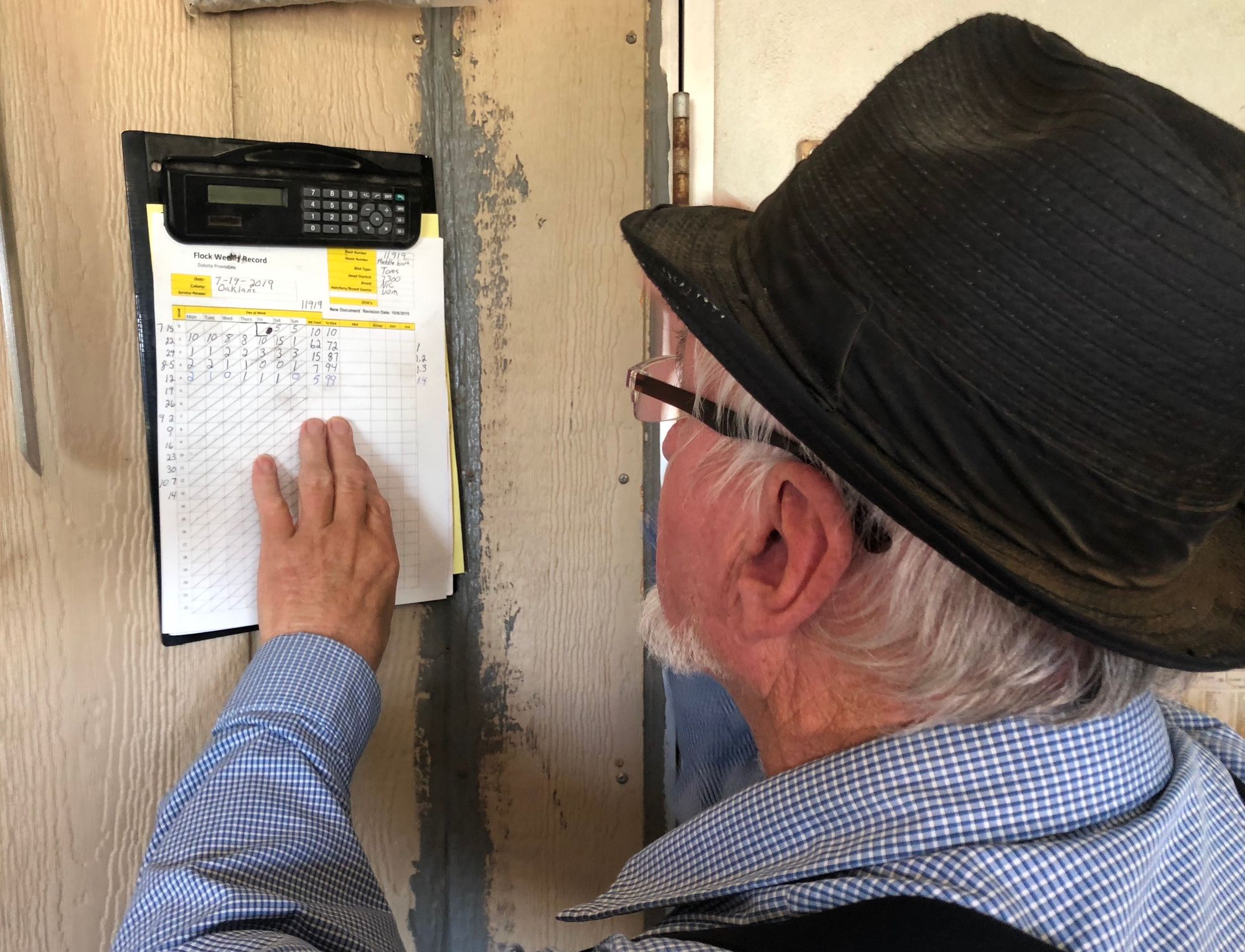

The head of the agricultural side of the system is John Wipf, 64, who oversees the raising of turkeys, hogs and dairy cattle at the Hutterite colony that houses 28 families a few miles west of Bridgewater. The farm also grows corn, soybeans, wheat, alfalfa and hay, mostly as feed for its animals.

The Oaklane Hutterian Brethren is one of 68 Hutterite Anabaptist colonies in the state; more than half of the colonies are part-owners of the Dakota Provisions turkey plant in Huron. Numerous colonies hold state permits to run CAFOs.

“I think the colonies raise every turkey produced in the state,” Wipf said.

Turkeys are one of several types of livestock animals raised at Oaklane, which holds a multi-species CAFO permit from the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources. The colony produces about 70,000 turkeys a year in three large barns.

The turkeys arrive in groups of about 7,500 from a cage-free birthing facility near Claremont, and weigh about three pounds after five weeks. The turkeys are raised at Oaklane without antibiotics and fed and watered for another 20 weeks to a finishing weight of about 45 to 50 pounds. At that point, they are shipped to the plant in Huron for processing, Wipf said.

Fans keep the turkeys cool in the summer and boilers keep them warm in winter. “If you had to be a turkey, this would be a pretty good way to live,” Wipf said.

The turkey wastes, known as litter, can build to about six inches per flock, he said. The litter is collected and brought to a composting barn on the entrance road to the colony.

The colony also has a dairy cattle operation with jersey cows, and a large farrow-to-finish hog operation, which includes 1,500 sows and produces about 40,000 head per year. The hogs are raised in an antiobiotic-free program and finish at a weight of about 280 pounds in barns in a field a short drive from the main colony. Their wastes are collected and piped to a storage pond about a mile away; the hog barns produce about 9 million gallons of waste per year, Wipf said. Pit additives are used to break down solids and reduce odors from the lagoon.

The colony follows its state permit in terms of when, where and at what level to spread its wastes on farm fields as fertilizer, he said.

The colony also operates a 300-head dairy operation with Jersey cows. The cows are housed in a confined barn with open that allow more air flow. The wastes from those animals are washed with water and flow down a slightly descending concrete floor to an underground waste area and then to a lagoon. The water from the process is recycled and reused the same way, Wipf said.

Wipf said the colony remains active in the use of numerous new technologies to constantly improve the efficiency and stability of its farm operations. Early in 2019, Wipf was honored for outstanding farm management and civic engagement by the South Dakota Pork Producers Council, which presented him with its Dedicated and Distinguished Service Award.