Delta David Gier has a lot to look forward to.

He’s approaching 20 years as conductor and music director of the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra, which has overcome financial challenges and a global pandemic to position itself as a cultural force on the Great Plains, drawing national acclaim for its community engagement and musical repertoire.

The 63-year-old Gier, his trademark tousled hair showing touches of gray, sat in a conference room at the Washington Pavilion in downtown Sioux Falls on a recent afternoon and pondered the unmistakable momentum of the state’s century-old orchestra, which concludes the 2022-23 season on April 29 with a performance of Beethoven’s Ninth Symphony.

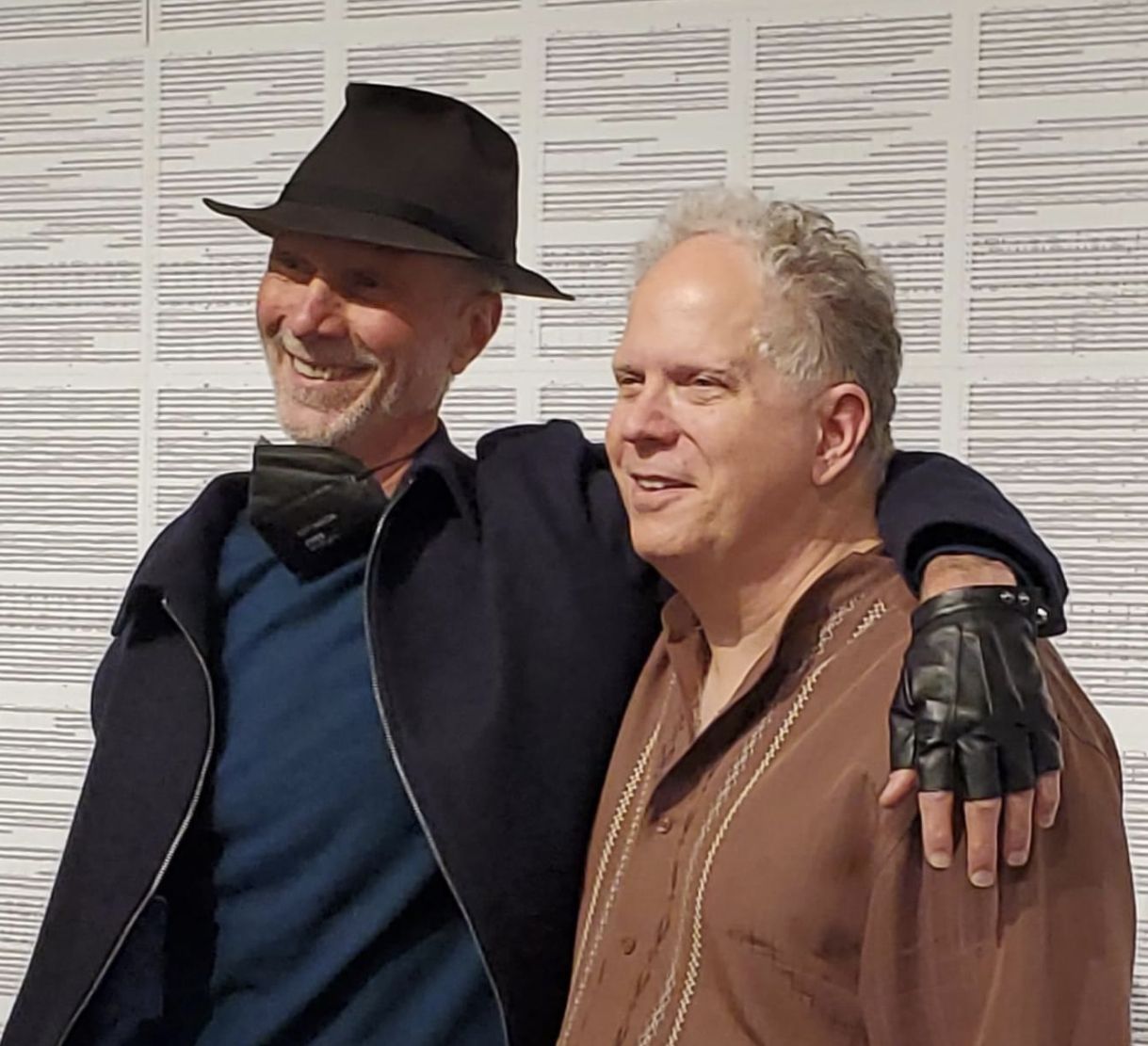

First there was the May 2022 article by New Yorker music critic Alex Ross, who dubbed Gier’s 75-member ensemble – just nine of them full-time – “one of America’s boldest orchestras” after attending a world premiere performance of the latest score from composer John Luther Adams at the Pavilion’s 1,800-seat Mary W. Sommervold Hall.

That high-level praise, plus the ongoing Lakota Music Project, Gier’s ambitious effort to meld orchestral styles with traditional Native songs and ceremonies, drew the attention of music-loving philanthropist and South Dakota native Dean Buntrock and wife Rosemarie.

Their $2 million donation became the largest in the organization’s history and will fund a performance in 2025 of a Pulitzer Prize-winning opera based on the Norwegian immigrant novel “Giants in the Earth,” which marks its 50th anniversary that same year.

‘An orchestra should serve its unique community uniquely’

It’s an exciting time, in other words, for a former New York Philharmonic assistant conductor who arrived in Sioux Falls in 2004 with the stated goal of finding a sense of place beyond standard-fare composers and prominent patrons and then actually embark on that search, shattering a few stereotypes along the way.

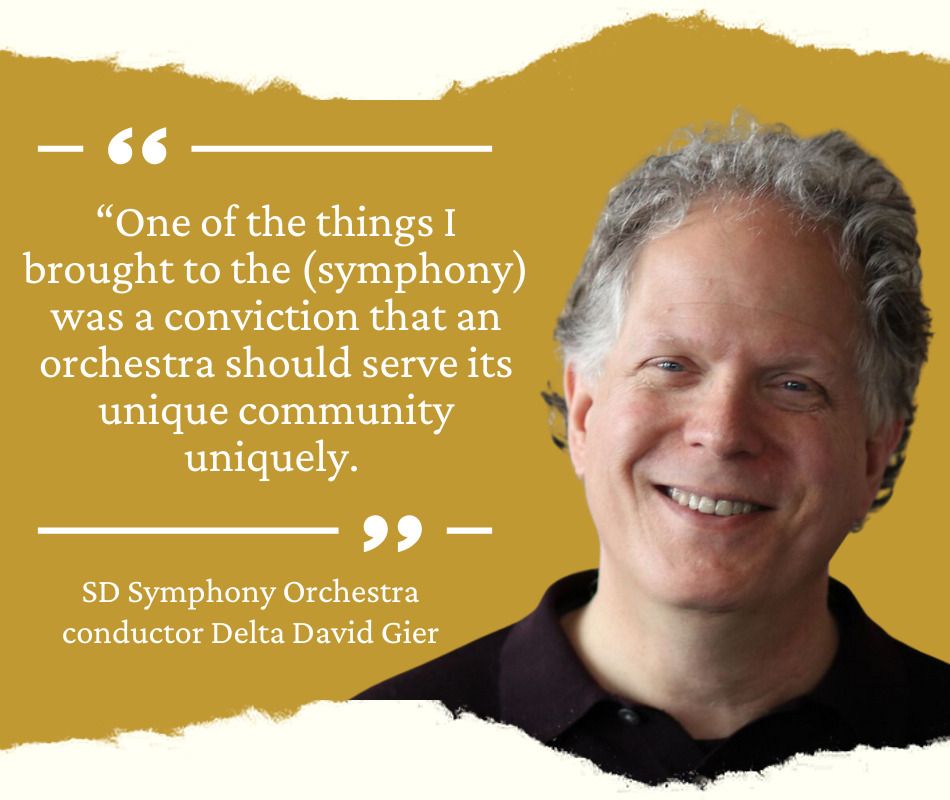

“One of the things I brought to the South Dakota Symphony was a conviction that an orchestra should serve its unique community uniquely,” said Gier.

“So what does South Dakota need in an orchestra? The first thing is that it needs great music, and we need to play great music as well as we possibly can, and we do that. But beyond that, what do you do with education and community engagement? And who are you engaging?”

Scott Lawrence, a longtime symphony board member who served as chairman from 2013 to 2022, remembers hearing that message two decades ago and being taken aback, just as audiences recoiled at times when hearing contemporary American composers championed by Gier rather than the easier listening of Mozart, Beethoven and Tchaikovsky.

“Never before had I heard someone talk about, ‘What we do with our communities?’” said Lawrence. “The symphony never talked about that kind of stuff. It was just music on the stage. That was what we did. But David had a vision and a passion for more than that, and it wasn’t just lip service. He lives it every day.”

The results are encouraging.

The nonprofit has an annual budget of $2.4 million. It reported net assets of $3.4 million in fiscal year 2022, up from $2.7 million the previous year.

That’s quite a turnaround from just over a decade ago when the Great Recession nearly forced it into extinction. Everyone, including Gier, took a pay cut at the time, only to encounter new challenges when COVID-19 hit in March 2020. Subscriptions are down 12% from the last pre-pandemic season, but the $2 million gift includes funds to boost marketing and outreach.

Delta David Gier’s long tenure an anomaly among conductors

Besides leading the 75-member orchestra, Gier wants to grow a crop of future musicians. The symphony’s educational programming includes a youth orchestra of 137 musicians comprising five student ensembles that has sent alumni to “top-shelf conservatories around the country,” according to Gier.

He frowned in contemplation when asked about his future and that of the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra, which celebrated its 100th anniversary last year. His wife, Angela, acknowledged that a dream job with a big-city orchestra could still emerge, but it’s not uncommon for conductors to have two or three orchestras. And Gier is mindful of the moment in Sioux Falls, a place not previously given to national acclaim in matters of the arts.

“Music directors generally come in with a bag of tricks and need to move on within 10 years or so,” said Gier, who was inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in 2020.

“But there are exceptions to that rule, and I like to think of myself in that category, where the ensemble and the conductor grow together. I think that’s certainly been the case. I’m a much better conductor now than I was 20 years ago, and the orchestra is much better. Nobody wants it to end now, and nobody foresees that.”

Newsletter: Get the latest from South Dakota News Watch in your email

Jennifer Teisinger, the symphony’s executive director, arrived in February 2019 and is still sorting through the benefits of The New Yorker article and $2 million donation. She’s more to the point when speaking of Gier’s future.

“We have not talked about him leaving,” Teisinger said. “We have only talked about him staying.”

A heart in search of harmony

First there’s the matter of the name. Delta David Gier. Affixed to someone who has conducted in New York and introduced America’s master composers to audiences from Bucharest to Brazil, it’s tempting to trace the alliterative appellation to Southern gentility or Manhattan’s Upper East Side.

Gier grinned at the folly of such assumptions, recalling his first conversation with legendary conductor Leonard Bernstein at the Tanglewood Music Center in western Massachusetts.

“Delta? Where the hell did you get a name like Delta?” pressed Berstein. “Are you from the South?”

“My parents are from southeastern Kansas,” replied Gier.

“That ain’t the South!” bellowed Bernstein, too enmeshed in his music to hear the full explanation.

The name stems from a period of convalescence that Gier’s great-grandmother spent with a Greek family in Kansas during a bout of tuberculosis. As she recovered, she doted on the couple’s young son, Delta, and vowed to pass on the moniker, which led to several generations of Giers using Delta as a first name but known by their middle name.

Gier’s father, Delta Warren Gier, was a biochemistry professor whose love of music was shared by David’s mother, Jonelle, who enrolled her son in musical kindergarten at the age of 3. Jonelle was an opera fanatic who sang in church choirs and played Broadway show tunes in the house. It was common for her husband to come home after a long day of teaching and sit down to the piano.

Their desire was for their son to be a more accomplished musician than themselves. But the nomadic nature of Warren’s visiting professorships complicated domestic harmony. Gier’s childhood included brief residences in Texas, Kansas, Missouri, North Carolina, Minnesota, New York and Arkansas, with the fabric of his parents’ marriage loosened at every turn.

They divorced when he was 7. Living with his father became problematic when Warren remarried and David clashed with his stepmother, which led him to leave home in 1974 at age 14 to live with his aunt and uncle in the Ozarks of northern Arkansas.

“It’s an area not exactly known for its arts, unless you’re picking up a banjo,” said Gier, who figured his musical career, such as it was, was over.

Turns out it was only beginning.

‘This is where I was meant to be’

Gier’s Aunt Ruth, in her 60s at the time, was in the process of publishing a seminal book on Arkansas wildflowers and became, as David put it, a “moral and spiritual compass” for her teenage nephew in the lakeside community of Cherokee Village.

After seeing David thrive in the high school music program, Ruth started driving him 90 minutes each way to take trumpet lessons with Arkansas State University professor and former Phoenix Symphony musician Dick Jorgensen, who was impressed by his student’s commitment.

“I won’t say that he was one of the best trumpet students I ever had, but his intense interest stood out,” said Jorgensen.

He pointed to Gier’s tenacity in earning the lead for his high school’s production of “South Pacific” and changing his curriculum and fitness regimen to meet the demanding application requirements for a Rhodes Scholar.

“He didn’t get the scholarship,” said Jorgensen. “But that’s the same energy he brought to becoming a conductor.”

Support News Watch: Donate to support our nonprofit journalism

Jorgensen introduced Gier to the prestigious Interlochen Center for the Arts academy in northern Michigan. He spent the next six summers there – first as a trumpet player and then as stage manager in college while attending Arkansas State University and the University of Missouri-Kansas City.

Interlochen introduced Gier to some of the nation’s finest conductors, including Henry Charles Smith, who later directed the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra. Watching these men work the podium, wringing every bit of inspiration they could from the surrounding ensemble, led to an epiphany for Gier as he took his first conducting classes.

“I learned that I loved music more than I loved playing the trumpet,” he said. “So when I first picked up the stick, it was like the heavens opened and said, ‘You will now do this.’ I sort of looked around and said, ‘Yeah, OK, this is exactly what I was meant to be.’”

Meaning behind the movements

Gier continued his studies at Tanglewood Music Center, the summer home of the Boston Symphony Orchestra, where he caught the attention of renowned conducting instructor Gustav Meier, who extended an invitation in 1984 to his University of Michigan graduate program.

Even then, Gier felt as if he were paddling upstream, trying to compensate for a turbulent childhood that didn’t fit the cultured pedigree of a classical conductor.

“I felt like I was playing catch-up,” said Gier.

“Particularly when I went to grad school, I was in a conducting class with people coming out of top conservatories from all over the world, people who had much more targeted education than I had. It was quite a motivator.”

He developed a collaborative style of not dictating to musicians what they should play but “inviting, facilitating, enabling the ensemble to come together.” This required strident study of not just the score but the composer, finding meanings beyond the movements.

Gier’s education continued as a Fulbright Scholar in Eastern Europe from 1988 to 1990, conducting orchestras in Romania, Poland and Slovakia, and introducing audiences to American composers such as Aaron Copland and Samuel Barber, a prelude to his motivations as a music director.

If there were doubts about his chosen profession during lonely days in city squares where the language eluded him, they were quickly dispelled when the curtain lifted.

“When you’re standing in front of an orchestra playing great music, I won’t lie, it’s a rush,” said Gier. “When everyone’s in sync and we’re all there to create something beautiful, there’s really nothing like it.”

Love blooms in New York City

The day he met his future wife, Gier was between Fulbright conducting trips and living in New York City, working as a waiter to make ends meet. Following the example of his Aunt Ruth, he looked for volunteer opportunities and attended a training session at Covenant House, a shelter for runaway children located near the Port Authority.

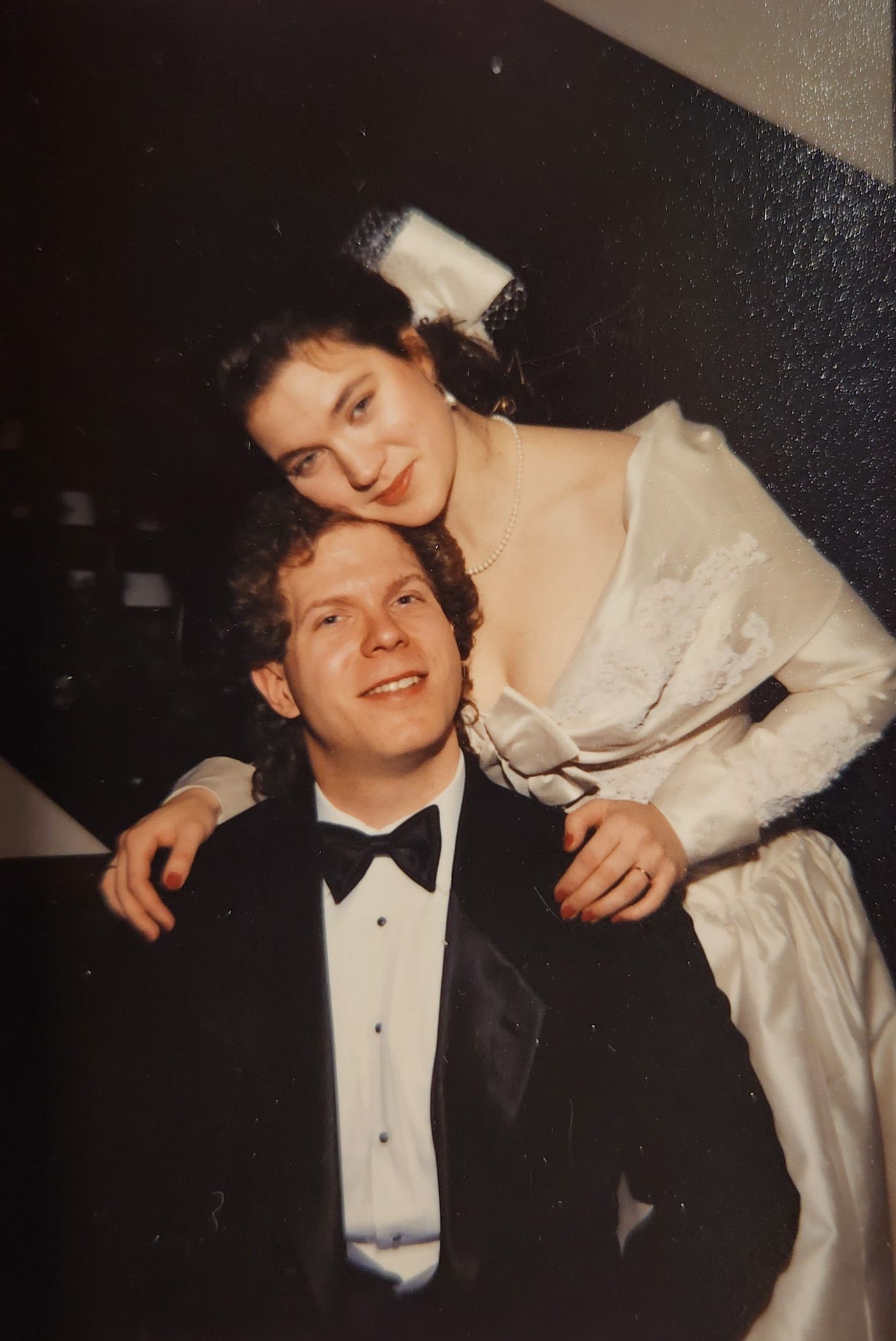

The date was March 13, 1988, marked in the memory of Angela Corbo Gier, an art school graduate from a blue-collar Italian family in Philadelphia who sat next to the young conductor.

“He was a starving artist, like holes-in-the-shoes days,” recalled Angela. “Very serious, living with four other musicians in a two-bedroom apartment behind Lincoln Center on the west side. I was living in Brooklyn, and I brought cookies from the bakery and a sandwich to the training session, and he had no food, so I offered him some of mine, and he turned it down.”

Later, Angela was getting her picture taken with other volunteers and saw David standing by the elevator, letting several groups go down without him. She finally realized that he was waiting so that he could ride the elevator down with her.

“That’s when I knew he had noticed me,” she said.

“We went out that night and were talking and there was an instant connection. I had never met anyone like him before. He wasn’t from New York and he wasn’t from Philly and he wasn’t Italian. I wasn’t sure what to do with him.”

When Gier left for Romania several months later, the couple wrote frequent letters and kept their relationship alive to the extent that David proposed marriage soon after he returned, eager to leave the loneliness of those travels behind.

When Angela’s father, a first-generation American citizen, asked him, “So how does a symphony conductor put bread on the table?” David responded, “One basket at a time, Mr. Corbo, just like any other waiter.”

They were married on New Year’s Eve 1989 on the Main Line in suburban Philadelphia, a private gathering of 50 guests on a day that Angela compared to a scene in the movie “Doctor Zhivago,” with mists of snow and icy exteriors.

When it came time for Gier to head to Europe again for his Fulbright scholarship in 1990, he had his bride by his side. Four years later, he received an invitation from New York Philharmonic music director Kurt Masur to serve as assistant conductor, putting his days as a waiter behind him.

“It was an exciting time,” said Angela, “because we had no idea what was going to happen.”

Opportunity knocks in South Dakota

The significance of conducting the Philharmonic, the nation’s oldest symphony orchestra, previously led by luminaries such as Gustav Mahler, Igor Stravinsky and Aaron Copland, was not lost on Gier, who arrived at Lincoln Center at age 34 ready to make his mark.

His debut performance in 2000 included Bernstein’s overture to Candide and Stravinsky’s Firebird ballet suite, with one reviewer noting Gier’s “ability to control this orchestra, not always an easy task. In his hands the energy was held in check until the last palpable moment and the concluding whirlwind was very effective.”

Gier was not present in 1999 when the New York Philharmonic performed the first-ever concert at the newly opened Washington Pavilion in Sioux Falls. That appearance set in motion a series of guest soloist gigs for Philharmonic musicians in the renovated high school.

One such musician was clarinetist Mark Nuccio, who played Carl Nielsen’s Concerto and took note of the concert hall’s quartzite panels, continental seating and superior acoustics.

“He said, ‘Hey David, I just got back from South Dakota – I played the Nielsen,’” recalled Gier. “I sort of scoffed and said, ‘How’d that go?’ He said it went really well and they were looking for a conductor. He asked if I was interested, and I asked if I should be. He said, ‘Yeah, you should be interested in this job.’ That was my first inkling.”

One thing Nuccio and other musicians considered a positive was the Pavilion’s Great Hall, which Gier a few years later said was “better than any hall in New York City except for Carnegie, better than anything in Lincoln Center.”

But there was the looming question of trying to build a viable orchestra in Upper Midwest flyover country, a place Gier could barely pick out on a map and had never considered in a cultural context.

“It still daunts us,” he said.

“People look at it from the outside, they see all these things we do, like with the Lakota Music Project, and we get a big ‘atta boy.’ But underneath it it’s like, ‘Well, it’s South Dakota. How good could it really be?’ So that’s been a challenge, and it was in some ways a question that I posed when I applied for the job in 2003.”

‘These Norwegian Lutherans are very serious about their music’

It was a critical time for South Dakota’s symphony, which was founded in 1922 at Augustana College but began making strides toward becoming a professional orchestra in the 1970s behind a small but dedicated donor base. A full-time string quartet was formed in 1979, followed by a wind quintet five years later for an orchestra of nine full-time musicians.

The city’s relative cultural isolation made it difficult to find part-time players. But Henry Charles Smith – the symphony’s conductor from 1989 to 2001 – made inroads in Minneapolis that helped fill the stage. Smith gave the orchestra a public face, leaned on illustrious composers and was instrumental in getting the Washington Pavilion and its Great Hall built in 1999, ending the symphony’s stint as a “gypsy orchestra” without a home.

Smith’s departure left a void, especially after replacement Susan Haig abruptly resigned during her second season in 2002, citing artistic and philosophical differences. That sparked a two-year search for a music director who could bring stability and excitement.

It was into this scenario that Gier arrived as the second of five candidates in the fall of 2003 to work a week with the orchestra. He spent his first night at a dinner hosted by Sommervold, the symphony’s first executive director, for whom the Pavilion’s performance hall was later named.

Surrounded by past orchestra presidents and steadfast supporters, the conductor found himself not intimidated but inspired by their commitment to elevating the quality of performance and building something meaningful.

“They were all very passionate about this orchestra and what it means to this community,” said Gier. “The state was like 30 years old when people decided to start an orchestra. These Norwegian Lutherans are very serious about their music.”

‘His conducting style was about the music and not himself’

Gier conducted the orchestra as part of his tryout, leading them through Shostakovich’s Symphony No. 5 in D Minor, a test of his ability to elicit depth and vibrance from the piece. According to Doosook Kim, the Korean master violinist who joined the South Dakota Symphony in 1995, he passed the test with flying colors.

“The audience really responded,” said Kim, who was part of the search committee. “What he pulled out of that piece, and how he helped the orchestra bring out all the elements, was exciting. He had a way of communicating what he wanted the orchestra to do, and we wanted to make music for him.”

Also on the search committee was violinist and educator Magdalena Modzelewska, who joined the Dakota String Quartet in 1998 after emigrating from Poland. She assumed all the candidates had mastery of the music and looked more to their personal traits, finding in Gier a grounded approach that reflected his arduous path to the podium.

“I remember getting the sense from the beginning that he was a good fit,” said Modzelewska. “There were a couple other conductors who were very flashy, but you could tell that they were all about themselves. David wasn’t like that. He cared and wanted to meet the musicians, and even his conducting style was about the music and not himself. Conductors are a bit like politicians in that they say they’re in it for public service, but so many of them are in it for themselves, for their own ego and power. David was different.”

A full-time commitment with South Dakota Symphony Orchestra

Gier was offered the job and accepted while continuing his role at the New York Philharmonic. He was required to spend at least 17 weeks on site with the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra. He and Angela maintained their home in Montclair, N.J., as she continued to work as a graphic designer in Manhattan. The couple’s two children, son Delta Gabriel and daughter Anna, were 10 and 7 at the time, making a potential move to the Great Plains a major undertaking.

During his 17-week run in 2004-05, Gier stayed with Sioux Falls lawyer and philanthropist Cathy Piersol, a longtime symphony supporter, and her husband, Larry, a federal judge.

“Our children were off at school, so we called David our other kid,” recalled Cathy.

“It was a familial relationship. He would play piano and study scores, and we would sort of tiptoe around when we were home. He was appalled that I loved Tchaikovsky so much and was able to elevate my musical taste. One time Larry came back after getting ready for work and said, ‘David has officially become one of our kids. I just saw him taking a vitamin pill out of the cupboard.’”

That year proved difficult for Angela, who felt separated from her husband’s inaugural stint as music director. She and the kids missed not just attending the concerts but hearing the excitement in David’s voice as he related the ebbs and flows of the performance.

“He was traveling back and forth, so what would happen is that we would hear the planning and all these things that go into preparing for a production, but we would never get to hear the concerts,” said Angela.

“He would leave for a week and come back, and I’d say, ‘Well, how was it?’ And he’d say, ‘It was good,’ and I’d be digging for details, but he was already on to the next thing. That concert was done. He’d get on the plane in Sioux Falls and have the next score on his lap heading back to New Jersey. So we figured we would have to move to South Dakota.”

Musical choices cause a stir with orchestra crowd

The 2004-05 season featured marquee composers such as Vivaldi and a pops performance from jazz saxophonist Brandon Marsalis, with Gier noting that it’s “a little dangerous for a first-year music director to play a bunch of music that nobody wants to listen to.”

But Gier was also praised by the Wall Street Journal for incorporating a work by Pulitzer Prize-winning American composers into each concert, an early indication that he preferred living, breathing arrangements rather than the warhorses of the past.

“This is art, which means it requires an investment on your part as an audience,” Gier told the Argus Leader in 2005. “You don’t have to like everything. If there are four pieces on the program and you like three, that’s fine. Talk about why you didn’t like it. It broadens the experience.”

For an orchestra looking to spark new subscription growth following a rudderless few years, those words raised eyebrows, just like there were grumbles in the hall when some of the more challenging pieces churned on. But Cathy Piersol, mindful of her afternoon conversations with the new conductor, urged her fellow patrons to let Gier’s philosophy unfold.

“Some people will never be comfortable with it, and some people were comfortable pretty quickly,” she said. “And the great middle to which most of us belong learned that the contemporary music had its own kind of beauty, maybe not Mozart or Beethoven, but its own kind of beauty, and it was of our era.”

Gier brings out the best in the musicians

Kim, the concertmaster and first violinist of the Dakota String Quartet, said she has a “love-hate relationship” with some of the contemporary pieces that the symphony performs under Gier’s direction.

“When the music is well-written and the composer has good training and foundation, it’s fine,” said Kim.

“But when it goes too far out in terms of being avante-garde or experimental, I become so upset as a performer, as I try to learn and make sense of it, and in some cases cannot relate to it at all. When the orchestra comes together and you hear us all play the piece together, sometimes, you say, ‘Ah, now it makes sense.’ And when it doesn’t, you just have to bite your lip.”

Kim supported Gier’s early efforts because she saw how he maximized the abilities of musicians and took time in rehearsal to explain compositional themes and motivations. She also respected how he wanted to explore all facets of the community, which included traveling to reservations to meet with Native American artists and learn more about their musical culture.

She wasn’t sure where it would all lead, but she was willing to follow along.

Conductor melds musical cultures and styles in South Dakota

It was the spring of 2005 when Gier started thinking about performing a concert for Martin Luther King Day the next year, following through on his commitment to extend the orchestra’s musical catalog to underserved communities.

“There was a young African-American woman in charge of MLK Day activities for a group, and I suggested that we work together,” Gier recalled. “And she said, ‘Sure, but if you really want to talk about racial prejudice in this state, you’ve got to look at Native Americans.’”

That conversation planted a seed that led to Gier meeting with Lakota and Dakota musicians to explore the possibility of a partnership. Barry LeBeau, a longtime arts advocate and United Sioux Tribes administrator who died in 2020, helped smooth over some of Gier’s early stumbles to make the collaboration possible.

“I learned that you can’t just show up in a room full of Native musicians and say, ‘Hey, I’ve got this cool idea. You guys should do it,’” recalled Gier with a laugh.

“At the initial luncheon, Barry saw me blunder my way through a bunch of ideas while being met with total distrust. It was like, ‘Who’s making money? Is this ‘Dances with Wolves’ and Kevin Costner again?’ All of that stuff. Afterward, Barry came up to me and said, ‘You know, you’re crazy, but I’d like to try to help you.’”

It took four years of learning and listening and building trust before a single note was played. When the classical musicians finally did sit down in 2009 with the Porcupine Singers, a renowned Lakota drumming group, it became clear that the melding of musical styles would be as challenging as overcoming cultural and language barriers.

“Our musicians read notes on a page, so the rhythms and tempos and pitches are fixed,” said Gier. “For a Native drumming group and cedar flute player, it’s not that it’s improvised, it’s very structured, but they don’t read music. It’s an oral tradition. What I learned about Lakota singing, for instance, is that the pitch and the tempo is determined by the emotion of the moment, so the keeper of the drum sets both those things.”

Treating culture with respect: ‘An open mind on both sides’

Doosook Kim recalled speaking with Keeper of the Drum Melvin Young Bear to determine what pitches or emotions might emerge during a particular concert or recording session, conversations that marked uncharted territory for a classically trained violinist.

“It was hard to find the balance,” said Kim. “We didn’t want to give them the impression that we were trying to impose Western classical music traditions on their culture but rather we were trying to do it through collaboration. It took an open mind on both sides. Our instruments have set intonations and scales, whereas their drum group leader uses different pitches every time, sort of like, ‘This is how I feel today.’ So we had to find solutions.”

When a series of false starts threatened to scuttle a three-hour rehearsal, Modzelewska recalled how Robbie Erhard, the orchestra’s principal cellist, stepped forward and sang along with the Lakota vocalist to keep him on pitch, a posture that wouldn’t have been possible without developing trust between the musical groups.

Gier saw it as a lesson that creating something beautiful doesn’t come without adversity. He had worked four years to bring the musical cultures together and there was still a staggering amount of work to be done, which struck him as relatable to real-life concerns in the state.

“It was a process of compassion on both sides,” he said.

“I can’t tell you how many times myself and others were just in tears because everybody wants this work so much, and we’re working so hard, and it comes grinding to a halt, and it doesn’t seem like there’s a way forward. It’s a metaphor for what needs to happen between races in this state altogether. It’s not a clear answer. It’s not like, ‘Just do this.’ It’s relationship-building and getting down in the muck and the mire together and working through things and creating something lasting.”

Bad hotels, horrible food, respect and honor

The South Dakota Symphony Orchestra received $95,000 in federal funds to perform a series of Lakota Music Project concerts in 2009, a tradition that continued with visits to reservations across the state for composition academies for Native students and orchestral performances with the Creekside Singers drumming group and Dakota cedar flutist Bryan Akipa.

“We’ve been on the road together for over 10 years now, sleeping in bad hotels and eating horrible food,” said Gier. “I mean, we’re friends. If we weren’t, we wouldn’t be making music together, and we’ve translated for each other in various ways. I think about going to a restaurant in West River, where the maître d at the restaurant totally disrespected this group of musicians I was with, and I said, ‘No, you don’t do that. These are my friends.’ It was just astounding to me.”

On the inaugural 2009 tour, during a performance at Sinte Gleska University on the Rosebud Indian Reservation, tribal elder Robert Moore, a trained musician who was instrumental in the project, wrapped Gier and Angela in a star quilt, symbolizing honor and generosity, a gesture that made the conductor’s eyes well up as he recounted the moment.

“I get choked up thinking about the reactions of the people on the gymnasium floor at Sinte Gleska or Red Cloud,” he said. “The resonance you see on their faces when they see their culture is treated with respect, it’s palpable. That’s the kind of stuff that politicians, quite frankly, can’t begin to touch.”

South Dakota Symphony avoids financial disaster

The community’s commitment to the symphony was tested during the Great Recession of 2008-2010, when mounting debt load and dwindling donations led to the orchestra almost shutting down in the fall of 2010.

The budget shrunk from $2.1 million in 2008 to $1.7 million two years later, with staff across the board – including Gier – taking pay cuts for the organization to survive. One of the casualties was a second string quartet that had been added in the early 2000s in partnership with Augustana to push the total of full-time musicians to 13.

When Augustana said it could no longer fiscally support that arrangement during the financial crisis, the quintet was cut and the number of core musicians reverted to nine (violin, viola, cello, bass, flute, piccolo, oboe). But even those jobs were tenuous. Lawrence, the longtime symphony board member who co-owns a Sioux Falls advertising agency, said that the orchestra came within weeks, or maybe even days, of folding as an organization.

“Those were some dark times,” said Lawrence, who used his role on the board to rally financial support.

“We had an emergency meeting at Minnehaha Country Club with our staunchest supporters and raised some operating capital to keep it going, and then we tightened our chin straps and went out and worked on raising the necessary money to keep things afloat. Our attitude through the whole ordeal was that it was too important of an organization to let fail.”

That was not merely a sentimental analysis.

Major employers such as Sanford Health and Avera Health and First Premier Bank often highlight the city’s cultural offerings when recruiting top talent, making the demise of a professional orchestra a question of commerce. That became evident when Lawrence asked a major benefactor to meet him in early 2012, when pay cuts and an emergency fund drive to raise $600,000 had failed to resolve the crisis.

“We still had maxed out our lines of credit with the banks to the tune of half a million bucks,” recalled Lawrence. “I said to this benefactor, ‘You put up $100,000 earlier as a loan to get us through that mess – would you be willing to forgive that as we move ahead?’ And he said, ‘Not only will I forgive that loan, I’ll go with you to all the banks and ask them to do the same.’ So we went around the city, bank by bank, and they all said, ‘Yes, we’re with you, we’ll release the note,’ and we were able to create some breathing room. The thing’s been growing ever since.”

Pandemic delayed orchestra’s Beethoven’s Ninth

Teisinger is attuned to the concept of timing, for better or worse.

When the pandemic hit South Dakota a little more than a year after her arrival as executive director, impeding public gatherings, she led an effort to keep the organization’s momentum alive through modified live performances and a broadening of digital offerings.

One notable hiccup was the production of Beethoven’s Ninth, set as this season’s finale, which was pushed back three times in 2020 and 2021 due to coronavirus concerns.

“Having hundreds of people on stage shouting at the top of their lungs on pitch didn’t make much sense during COVID,” conceded Gier.

The orchestra’s business model, which calls for 25% of revenue to come from ticket sales and the rest from private/corporate donations and grants, was built to handle such adversity, but only if community partners remain engaged.

In that respect, the symphony’s 100th anniversary in 2022 couldn’t have come at a better time, with special celebrations planned for the April season finale and a world premiere performance of “An Atlas of Deep Time” by Pulitzer Prize winner John Luther Adams.

Adams, one of the American composers that Gier had championed through the years, was in attendance in 2016 when the symphony performed one of his earlier nature-based works, “Become Ocean.” He was impressed with the presentation and began discussions with Gier about writing an original score to coincide with the orchestra’s 100th anniversary gala.

New York writer heartened by South Dakota performance

As that plan became reality, Adams invited Ross, the influential New Yorker critic, to come to Sioux Falls in April 2022 to review his new piece, a sort of vindication of Gier’s devotion to highlighting contemporary works from the podium at the Pavilion, despite the occasional fuss.

“David’s consistency of developing relationships with American composers is behind the relationship he has with John Luther Adams, which resulted in the world premiere and Alex Ross coming to hear the music,” said Teisinger. “Alex Ross was not coming to hear the South Dakota Symphony Orchestra. Alex Ross was coming to hear the premiere of John Luther Adams’ piece.”

Once seated and presented with not just the Adams score but an anniversary celebration of the symphony, The New Yorker critic was heartened by what he saw. His review noted that the orchestra featured a “large array of freelancers” and “struggled in spots.” But he focused on efforts to honor longtime symphony musicians and staffers, including retiring librarian Pat Masek, whose service to the orchestra dated back 60 years.

“I’ve experienced very few concerts at which a classical-music organization seemed so integral to its community,” wrote Ross, who highlighted a moment when Teisinger took the stage and asked former members of the ensemble to stand and be recognized.

“In a crowd of more than a thousand people, dozens rose their feet,” Ross wrote. “Nothing of the sort could have happened in New York, Los Angeles, London or Berlin.”

South Dakota native responded to national story with record gift

One of those intrigued by the New Yorker article was Dean Buntrock, the northeast South Dakota native and founder of Waste Management, which reported nearly $20 billion in revenue in 2022. Buntrock and his wife had donated generously to St. Olaf College, his alma mater, the Lutheran Church in America and the Chicago Symphony Orchestra.

He called Augustana University president Stephanie Herseth Sandlin, with whom he had a family connection, and she directed him to Teisinger and Gier. They learned he was interested in exploring ways to help them enhance programming beyond their established budget, creating more opportunities like scenes depicted in The New Yorker piece.

“He came here twice,” Gier said of Buntrock, gesturing to the Pavilion’s conference room. “The first time with his wife, and the second time with his lawyer and accountant.”

The discussions resulted in a $2 million gift over four years, with directed funding tied to marketing, fundraising and statewide outreach. Part of that means the Lakota Music Project, which achieved national stature with a 2019 concert at the National Museum of the American Indian in Washington, will have the resources necessary for original compositions, academies and touring.

Symphony to perform opera based on Norwegian immigrants

The project has evolved into Bridging Cultures, an initiative aided by the Bush Prize for Community Innovation awarded to the South Dakota Symphony in 2016. The program will explore musical partnerships with immigrant and refugee communities and highlight artists such as South Asian composer Reena Esmail and Iranian composer Niloufar Iravani, who will perform as part of this year’s season finale on April 29.

What really caught Buntrock’s attention as a Norwegian descendant, though, was Gier’s effort to revive the 1951 Pulitzer Prize-winning “Giants in the Earth” opera by Douglas Moore, based on Ole Rolvaag’s 1925 novel depicting the struggles and sacrifice of Norwegian settlers in the Dakota Territory.

The opera premiered in 1951 at Columbia University but has been performed rarely since, and it has never been recorded. Gier met with Charles Berhdahl, a symphony patron and descendant of Rolvaag, to better understand the themes behind the story and its author, whose writing cabin can still be found on the Augustana campus.

Buntrock’s gift will make possible a 2025 multimedia symphony performance of the opera, which Gier describes musically as “mid-20th century Americana,” in the state where the story is based, on the 100th anniversary of the “Giants of the Earth” novel.

It’s a full circle moment for the conductor, who was handed a copy of the book by symphony patron and Center for Western Studies founder Art Husboe at that introductory dinner 20 years ago in Sioux Falls, where he first started searching for a sense of place.

“I think ‘Giants in the Earth’ fits with our Bridging Cultures theme,” said Gier.

“It’s people who came here 150 years ago looking for a new life out of desperation because they couldn’t feed their families at home. Now we have all these refugees coming from all over the world, and it’s really the same story, like the Karen people up in Huron working at a turkey plant. I kind of doubt the Norwegians wanted to leave home. But they were desperate, they had to leave, and how is that much different from Somali refugees fleeing war in their home country and ending up in Sioux Falls, of all places? How do you build a new life?”

Finding meaning in the message

In March 2022, David and Angela traveled to London to celebrate the wedding of their daughter, Anna, now 26 years old and pondering her career path after two degrees at Oxford University. Also in their orbit is son Gabriel, 30, who is married and living in Austin, Texas, where he designs video games.

“We tried to keep him away from video games his entire childhood,” noted David with a grin. “We should have tried keeping him away from medicine or law.”

Summer travels for Gier encompass work and music, which are one and the same, guest conducting from St. Louis to Singapore and providing leadership for the Christian-based Crescendo Summer Institute, tapping into spirituality that dawned during his days with Aunt Ruth in Arkansas.

It’s not uncommon for conductors to work into their 80s and 90s – their life expectancy is longer due to constant arm motion and high IQ – and Gier shows no signs of slowing down.

But after all the shifting and uncertainty of his childhood, it’s nice to have a home base he can count on, a community that he understands and cultivates and aims to improve. Angela has a garden that she nurtures each year, full of colorful wildflowers that brighten her days.

She compares this to what her husband has found in South Dakota, the way music and relationships draw serenity from the soil.

“David plants gardens with people,” she said. “And you have to stay in a place to do that.”

Symphony helps people ‘engage with something of beauty, of meaning’

It’s a message that resonates with Modzelewska, whose violin has been a mainstay of the city’s arts scene for a quarter century.

“When I came here straight from Poland 25 years ago, I thought I would get my green card and go somewhere else,” she said.

“But then other prospects just started not looking so good compared to here. It’s a very rewarding atmosphere, and David’s a big part of that. He’s a great friend to the musicians, making sure that we can talk freely. And he knows where we are with our families and personally, and we know about him too.”

Sometimes his spirituality comes to the fore, taking a break in rehearsal to describe the faith and philosophy behind a composition, helping the orchestra understand the connection between their instruments and the message, and the people that come to hear them.

“If you believe that beauty comes from God, it’s not disconnected at all,” said Gier.

“The composers that we most revere believe that they were participating in something beyond themselves, something that transcends our mundane existence. I think that’s one of the greatest things of value a symphony does is give people the opportunity to come and not just listen passively but to engage with something of beauty, of meaning. They’re like philosophers, these composers. They lift our thoughts above ourselves. In a perfect world, we should leave the concert hall thinking about others rather than ourselves.”