The COVID-19 pandemic and the economic hardships it is causing will likely result in a wave of personal, farm and small-business bankruptcies in South Dakota and beyond in the coming months that will be both a result and a cause of a wider economic crisis spurred by the coronavirus.

So far, federal aid and unemployment programs, and several months of restricted access to the court system, have delayed a rise in bankruptcies from showing up in court filings.

But increased rates of unemployment, reduced incomes of people at all levels of the economy and a coming debt crisis will all play a role in the anticipated bankruptcy storm that could affect a wide range of individuals and businesses, including people who long saw themselves as financially stable, said Breck Miller, community relations director for Lutheran Social Services Center for Financial Resources in Sioux Falls.

“It would not surprise me at all if we do see an increase in the number of bankruptcy filings,” Miller said. The pandemic “really put a lot of people in a financial bind, and I think it’s going to strike across the demographics. It’s not just a low-income thing.”

Federally backed financial assistance programs have helped keep food on many family’s tables during the pandemic and have so far helped many of the hardest-hit South Dakotans stave off bankruptcy.

Mortgage forbearance, which allows for a delay or reduction in house payments, was granted as part of the federal CARES Act, and helped some homeowners manage debt. Temporary aid was also provided through new payment options from credit-card companies, and some borrowers were granted a pause in student loan payments.

But as federal assistance programs expire, and private lenders start seeking back payments on home and car loans, experts say many people in financially vulnerable positions will soon find that the debt they took on during the worst of the pandemic has become too much to handle.

“The scariest thing for us in our office was that payment options weren’t necessarily laid out, or at least not understood clearly when people took the forbearances,” said Miller.

"It would not surprise me at all if we do see an increase in the number of bankruptcy filings ... and I think it's going to strike across the demographics. It's not just a low-income thing.” -- Breck Miller, Lutheran Social Services

Mortgage payments delayed through forbearance still must be paid, sometimes as soon as the forbearance period ends. A homeowner could be on the hook for hundreds or even thousands of dollars in back payments that must be made and carry the risk of defaulting on loans.

Back payments alone will drive more people to seek bankruptcy protections in the coming months, said Clair Gerry, a bankruptcy attorney from Sioux Falls.

“For that reason alone I would expect to see a big uptick in Chapter 13s,” Gerry said of the personal bankruptcy filings.

As of late July, 16,000 South Dakota residents were unemployed, and many were forced to turn to credit cards or drawing down savings to survive, Miller said. As of August, those unemployed workers lost the $600 weekly enhanced unemployment benefit created by Congress as part of its pandemic relief efforts.

A rising wave of bankruptcies could lengthen the pandemic’s economic recession as small businesses and consumers struggle to restructure their debts or sell off what they own or write off debts they can’t pay. The burden has already been immense for many families at all income levels in South Dakota, many of whom have said they couldn’t withstand an unexpected $400 expense without taking on more debt even before COVID-19 hit.

Consumer spending, meanwhile, is sure to fall and the economy overall will suffer, said Joe Mahon, an economist and outreach director at the Minneapolis Federal Reserve Bank.

“Think of all those people who lost their jobs and lost their incomes,” Mahon said. “Even with the unemployment benefits that they might have been receiving, they’re probably thinking more about hanging on to their discretionary money rather than going out and spending on appliances and clothing and things like that.”

If consumers are stuck paying off debts, they can’t spend their money at local businesses, many of which also took on additional debt to survive the pandemic and which will be less able to expand. That will result in fewer job openings for people trying to return to work as their unemployment runs out and the economy continues to open up

“We know that that large of a shock to employment is going to have a long and persistent feedback effect on the economy,” Mahon said.

Exactly when the bankruptcy bomb will go off is anybody’s guess at this point, economists and bankruptcy experts say, but they worry it is only a matter of time before filings rise rapidly.

“My phone calls right now, a substantial part of them, are asking about what happens when this is over, with people asking, ‘Should I come see you?,” Gerry said. “Based on those calls, I just know there’s a storm looming … everybody is predicting that there’s going to be a lot of bankruptcies filed by fall or winter.”

Relief efforts stemming bankruptcy flood, for now

So far, 2020 has been a relatively slow year for bankruptcy courts. Nationwide, total bankruptcy filings were down about 23% compared to the first six months of 2019. In South Dakota, by the end of July, bankruptcy filings were down about 16% compared to the first seven months of 2019, said South Dakota Bankruptcy Court clerk Frederick Entwistle.

Much of the decline is due to a near total shutdown in bankruptcy activity at courts that went dark during the last half of March and all of April, Entwistle said. But by the end of May, bankruptcy filings had returned to near-normal levels in South Dakota. By the end of June, 416 personal bankruptcies had been filed in South Dakota during the calendar year, according to data from the American Bankruptcy Institute.

There are several reasons bankruptcy filings have yet to rise. One of the biggest reasons may actually be the relatively high unemployment rate. At the end of June, 7.2% of the South Dakota workforce was unemployed, which is more than double the pre-pandemic unemployment rate of 3.1% recorded in March.

Bankruptcy attorneys and financial counselors have recommended to clients that they hold off on filing for bankruptcy until the worst of their financial losses have ended. Often, that meant waiting until finding a job and figuring out what their new monthly income would be. If an individual files for bankruptcy but has to keep living off of credit cards or other forms of debt, any debt incurred after the initial filing won’t be discharged or reorganized as part of the bankruptcy proceeding.

There are other good reasons to hold off on filing for bankruptcy right now, Gerry said. Sometimes waiting until after a tax return has been received and spent is a good idea, for example. Spending down one-time payments such as stimulus checks or other state or federal financial assistance is also a good idea to do before filing for bankruptcy.

“When COVID hit, everyone was kind of holding their breath. That’s why we’re waiting for the storm to break, until people get back to work and we find out what the new norm is,” Gerry said. “When they don’t have a paycheck coming in, they’re not being garnished. And right now, there’s a lot less collection-type action because collectors know there’s not much they can do at this point.”

South Dakotans, in general, also tend to avoid bankruptcy. The state currently ranks 45th lowest in the per-capita rate of bankruptcy filings out of the 50 states and has had one of the lowest per-capita bankruptcy filing rates for more than a decade. Over the past five years, there have been fewer than 1,100 personal bankruptcies filed in the state each year. In 2019, just 964 people or married couples filed for either chapter 7 or chapter 13 bankruptcy.

Recessions, though, tend to push people beyond their financial limits faster and farther than they can cope with. In 2010, when the effects of the Great Recession of 2008 peaked in South Dakota, 2,000 people filed for bankruptcy protection, nearly double the number from before the Great Recession began.

Only a matter of time before a crash

Experts cannot predict just how bad the COVID-19 economic fallout will be, but the picture is not likely to be pretty. Unlike the Great Recession, which took years to play out and left agriculture relatively unscathed, the COVID-19 economic crisis has hit every state at roughly the same time and in much the same way.

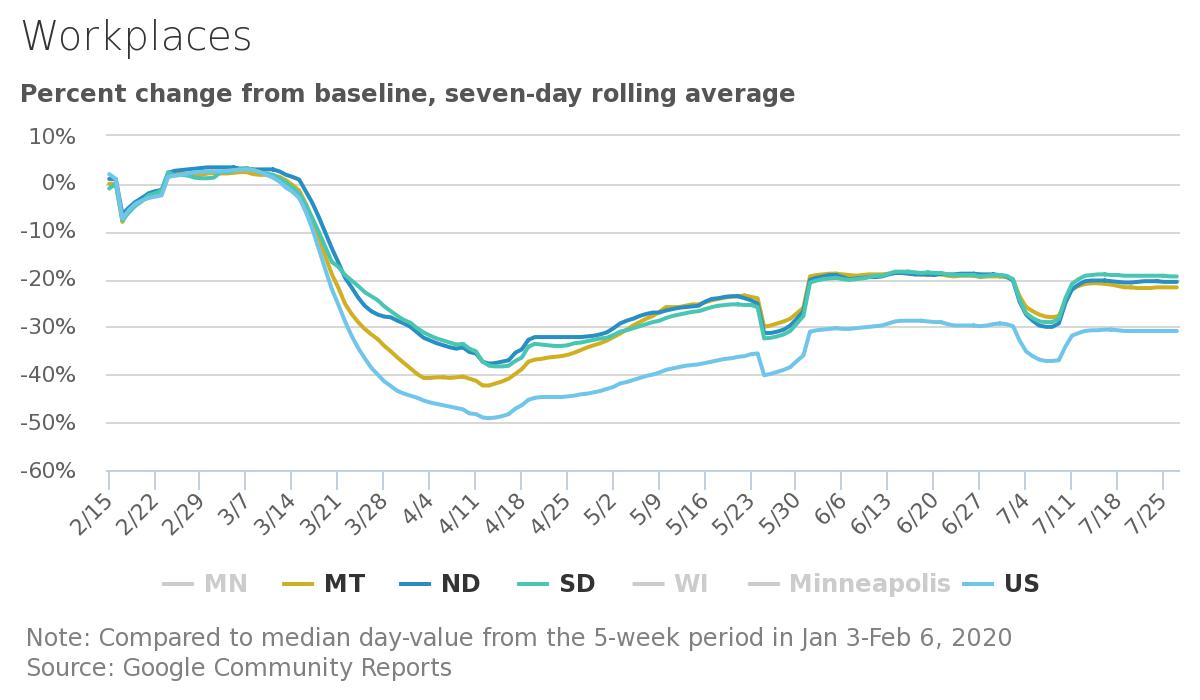

South Dakota, despite its lack of state government mandated business closures or other mandated social distancing measures, fell off the same economic cliff as its more restrictive neighbors, Mahon said. Traffic at businesses of all types, but most especially bars, hotels and restaurants, cratered in April and didn’t return to pre-pandemic levels until July.

“You still had people losing their jobs. We know employment has fallen in the state. So you would expect that to have that feed-through effect on household finances, that will ultimately show up in bankruptcies,” Mahon said.

COVID-19 also came at a time when farmers and ranchers, South Dakota’s economic bedrock, were struggling against a trade war and low prices for grain, soybeans and cattle. In fact, January and February of 2020 saw overall bankruptcy filings in South Dakota increase over the same period in 2019 due to a jump in farm bankruptcies, said Gerry.

“We were doing a lot of restructuring or mediation for farms near the first part of the year to get ready for spring planting,” he said.

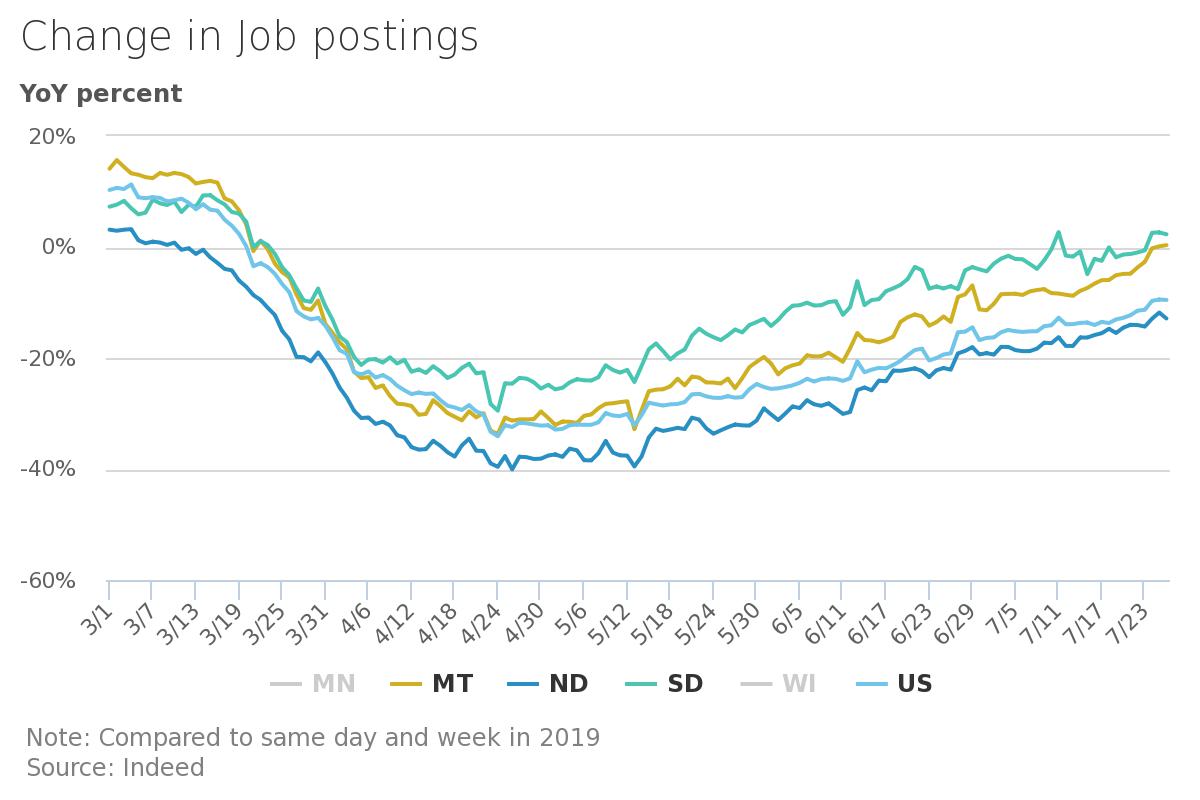

The news isn’t all bad, though. More South Dakota small businesses have reopened and have started hiring again when compared to other states. South Dakota also boasts slightly more new job postings than in its neighbors, according to data from the Minneapolis reserve bank.

Much of what happens over the next few months will depend on what Congress comes up with as far as economic stimulus, and how long it takes those currently unemployed to get back to work. Avoiding a surge in bankruptcies, though, will take a lot more stimulus and far faster employment and wage growth than is likely to occur.

“It would take more than the stimulus that was talked about last time,” Gerry said. “That just kept people fed, basically … doing that again and taking care of emergencies is not going to cure the future.”

The basics on bankruptcy

Bankruptcy is handled entirely by the federal court system. The U.S. Bankruptcy Code, the set of laws governing bankruptcy in the U.S., allow for several different types of bankruptcy depending on who or what entities are filing.

- Individuals can file for Chapter 7 or Chapter 13 bankruptcies.

- Chapter 7 is typically used when a debtor doesn’t have a home or car they’re trying to keep. All debts that can’t be settled after a debtor’s major assets are sold are discharged under Chapter 7.

- Under Chapter 13 bankruptcy, debtors are allowed to restructure past due payments in order to avoid such things as foreclosure on a home or repossession of a car.

- Municipalities, including cities, towns, villages, taxing districts, municipal utilities, and school districts, may file a Chapter 9 bankruptcy that allows them to reorganize.

- Businesses may file bankruptcy under Chapter 7 to liquidate and shutdown or under Chapter 11, which allows them to reorganize and restructure debt so they can continue to do business.

- A Chapter 12 bankruptcy allows family farmers and fishermen to propose and execute a plan to pay past due debts over the course of three to five years and thus avoid foreclosure.

- Bankruptcy filings that involve parties from more than one country are filed under Chapter 15.

Source: U.S. Bankruptcy Code