Significant direct oversight of the federal Paycheck Protection Program, which provided more than $800 billion in forgivable loans to U.S. business during the pandemic, was placed in the hands of the community banks and lending institutions that issued the loans.

Jaime Wood, South Dakota director for the U.S. Small Business Administration, said the SBA has entrusted much of the vetting of PPP applications to the lending agencies that processed the loan applications and distributed the money. In many cases, those lenders had pre-existing relationships with borrowers who sometimes received large sums of money.

The lenders are responsible for confirming how many employees the applicant has, where the business is located and whether it is legally registered, among other things, Wood said.

“We’re heavily leaning on the input that the community lenders give,” Wood said. “Many businesses have accounts with these lenders already … and we’re pretty confident in the integrity of the Paycheck Protection Program.”

PPP loans were designed to help businesses continue to pay expenses for employees and other costs during the major slowdown during the pandemic. Loans are forgivable if the money was shown to be used for the purposes outlined in the PPP application.

A South Dakota News Watch investigation published on Oct. 11 has raised questions about whether a business owned by Chris Cammack, son of Senate Majority Leader Gary Cammack, operated in South Dakota and had employees working there during the pandemic. Chris Cammack applied for and received more than $300,000 in PPP loans for Prairie Mountain Wildlife Studios, a business he said operates in Union Center, S.D., but which property records and legislative testimony by Chris Cammack indicate actually operates in Cypress, Texas.

Chris Cammack did not return calls and emails for comment for the Oct. 11 article and did not return a call or email seeking comment for this article.

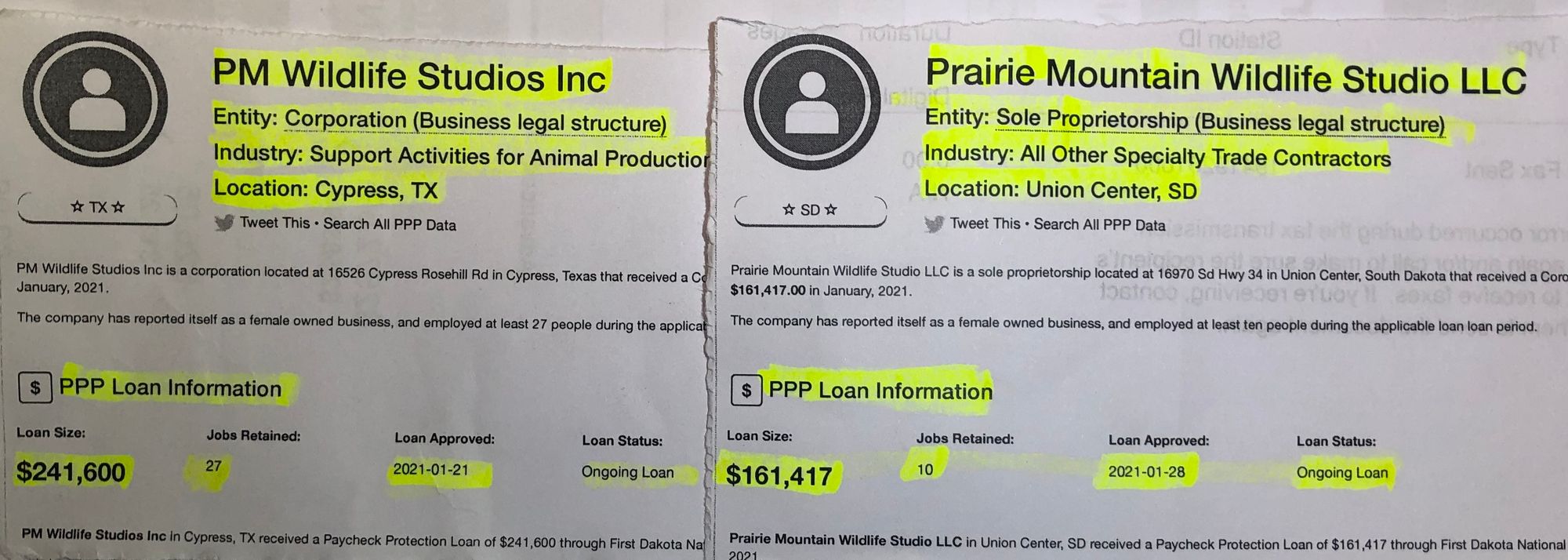

Prairie Mountain Wildlife Studios in Union Center received a $153,600 PPP loan in April 2020 to protect 10 jobs with an annual payroll of $737,280 in 2019, according to SBA records on Federalpay.org.

The business in Union Center received a second PPP loan of $161,417 in January 2021, also to protect 10 jobs. Both loans were designed to cover payroll expenses, the records show.

Meanwhile, Chris Cammack’s business called PM Wildlife Studios in Cypress, Texas, received a $241,600 PPP loan in April 2020 to cover payroll, utilities and mortgage interest, according to SBA records. That loan was to protect 25 jobs at an estimated annual 2019 payroll of $1.16 million.

PM Wildlife Studios in Texas then received a second PPP loan of $241,600 in January 2021 to cover payroll for 27 jobs at an estimated annual payroll of $1.16 million, according to Federalpay.org.

In South Dakota, through two rounds of PPP lending in 2020 and 2021, about 300 qualified SBA-approved lenders made more than 64,000 loans valued at $2.7 billion, according to federal records. Nationally, the PPP program that has now ended had nearly 12 million loans valued at almost $803 billion over 2020-21.

An SBA regional official said he was unable to discuss the PPP loans made to Cammack or any other individual applicant.

Chris Chavez, spokesman for the regional SBA office based in Denver, said the SBA takes any complaint of potential fraud very seriously. Chavez said in an email to News Watch that the SBA wants to hear from anyone who suspects fraud has been committed within the PPP program.

“The SBA takes fraud seriously, and, as such, all applicants are required to provide certification of their eligibility upon application,” Chavez wrote. “Misrepresentation of eligibility is unlawful, and, when appropriate, these cases are referred to the Office of the Inspector General. The Office of Inspector General and the agency’s federal partners are working diligently to resolve the fraud incidents. The SBA encourages anyone suspecting fraud or misuse of relief programs to visit sba.gov/fraud.”

Chris Cammack is not known to be under investigation and has not been charged with any crime at this time.

Several criminal cases alleging criminal fraud in the PPP program have been filed by federal authorities.

According to the law firm Arnold & Porter, which is tracking COVID relief fraud, several criminal cases of PPP fraud are pending across the country. In one case, a Delaware woman was charged with inflating revenues and number of employees at her business to obtain $246,000 in PPP loans. In another case, a Tennessee man was charged with obtaining $6 million in PPP loans by inflating the revenues and number of employees at his company and then misusing the PPP funds to buy a home and a car.

Wood, SBA director in South Dakota, said she is not directly involved in auditing of applications or PPP loans awarded. While refusing to comment directly on the loans obtained by Chris Cammack, Wood said it was not uncommon for a business owner to live in one state and have businesses qualify for PPP loans in another state.

The lender on both PPP loans made to Cammack’s business in South Dakota, and one of the PPP loans made to his business in Texas, was First Dakota National Bank. First Dakota is based in Yankton, S.D., and has branches in several South Dakota cities.

Dave Kroll, chief lending officer for First Dakota, said his institution made more than 4,000 PPP loans totaling more than $200 million.

Kroll said privacy laws prevent him from speaking about any specific loan or applicant.

Kroll said First Dakota is proud of its efforts to efficiently provide loans that helped businesses stay afloat during the uncertainty of the pandemic. Kroll said working with the rapidly changing rules of the PPP program and desire to distribute funds quickly created a hectic time for lenders.

Kroll said all PPP applicants were required to provide documentation of business location, operations and employment. In general, if the proper documentation was submitted, First Dakota approved the loans and distributed the federal funds.

“Because of the nature of the program, we followed what was required,” Kroll said. “If they provided everything that was required, we certainly weren’t denying them access to the PPP program.”

Kroll said First Dakota felt comfortable with the PPP loans it made because the bank followed program rules closely and in part because the bank knew many of its PPP customers through prior relationships.

“As a whole, First Dakota does business in South Dakota largely with people we know,” Kroll said. “It was still a manual process, and I feel good in our due diligence in reviewing the PPP documents that were required.”

Kroll said lenders and applicants who engaged in the PPP program were generally aware that much of the resulting loan information would be open to public review, as it would with any government program.