A new industry launching in South Dakota will use manure from dairy farms to generate usable natural gas, creating a new income stream for some South Dakota farmers and reducing greenhouse gas emissions along the way.

California-based renewable energy company Brightmark Energy announced plans on Feb. 5 to capture, refine and sell methane gas rising off the decaying manure produced at three dairy farms in Minnehaha County near Sioux Falls. The project could be the first of many renewable natural gas projects built at South Dakota dairy and hog farms and is being driven by rising demand for cleaner, more sustainable energy, experts say.

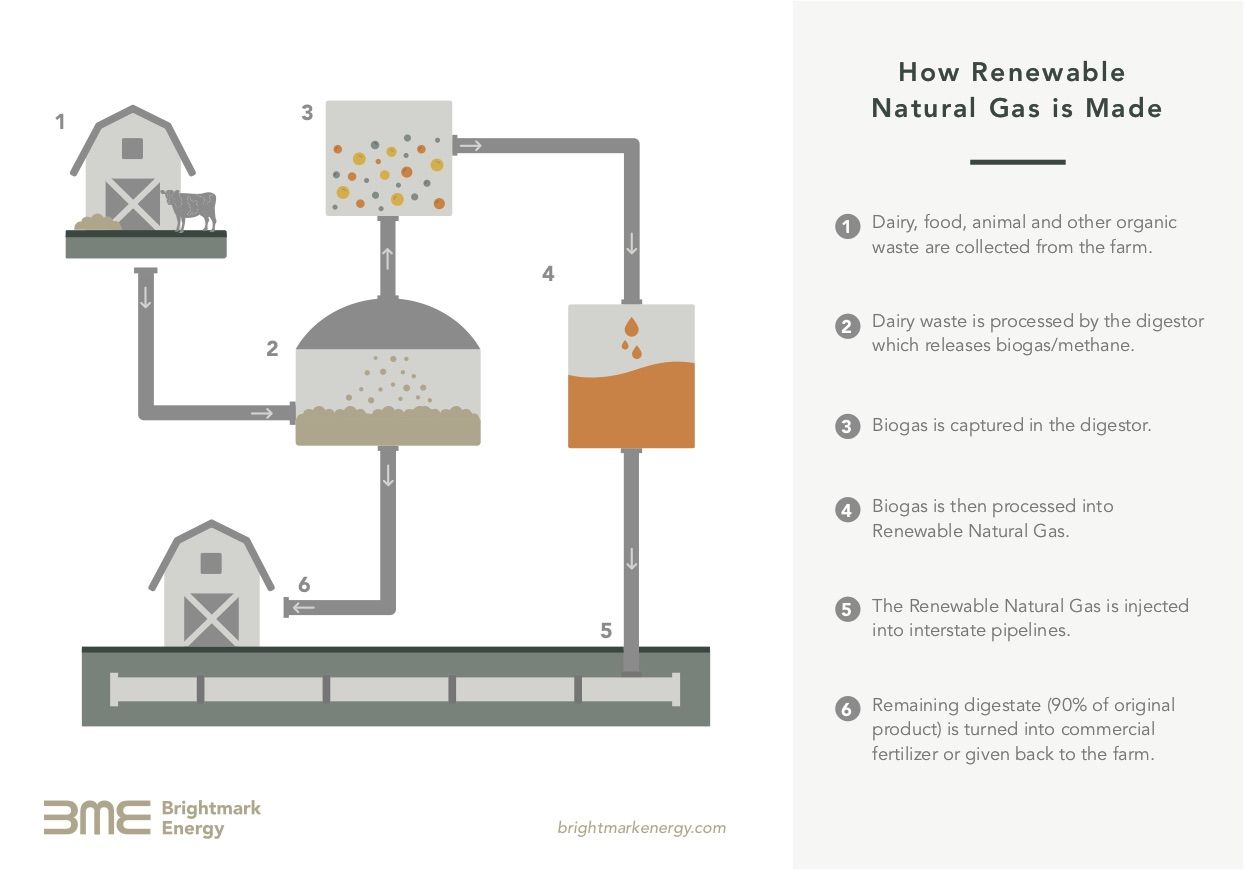

The Brightmark Energy project will collect manure from nearly 12,000 dairy cows at the Boadwine, Pioneer and Mooody County dairy farms. The manure will be placed in large, oxygen-free tanks and, essentially, left to rot. One of the byproducts of rotting manure is methane gas, a major component of the natural gas already piped to thousands of South Dakota homes. Brightmark expects to harvest enough of the gas each year to cover the annual average energy needs of more than 2,400 homes, based on average energy consumption as reported by the Energy Information Administration.

“Basically what we’re doing is, we’re taking the manure and putting it in a process that is highly efficient and environmentally friendly … so we can use (methane) for heating, cooking, powering cars, etcetera that otherwise would just end up not being utilized and create a greenhouse gas impact,” said Bob Powell, CEO of Brightmark Energy.

Methane gas traps heat in the earth’s atmosphere at a far greater rate than carbon dioxide, making it a significant contributor to global warming.

Capturing methane and burning it to heat homes or to fuel trucks can significantly reduce the impact that concentrated animal feeding operations and landfills can have on climate change, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency.

Once filtered, the manure-derived methane is essentially the same gas that is already used as fuel at homes and businesses across South Dakota. Brightmark’s plan is to pump the gas collected from the dairies directly into an existing interstate natural gas pipeline system located near the farms.

Exactly how Brightmark will inject its gas into the pipeline hasn’t been worked out yet, Powell said. The project is still at least 18 months away from producing any gas but there are really only two options: connecting a pipeline from the collection sites to the interstate pipeline or loading the gas into pressurized tanks and trucking it to a pipeline terminal.

For Lynn Boadwine, majority owner of the Boadwine, Pioneer and Mooody County dairies, the chance to turn a small profit from a potentially harmful animal byproduct was an opportunity he did not want to miss. But just as important, he said, is the potential to produce a cleaner fertilizer that can be used to help grow food for his dairy cows.

Part of the methane harvesting process keeps manure under heat for long periods of time which can kill harmful bacteria. There is also a chance that keeping the manure contained in closed tanks while it decomposes will help reduce the odors generated by each dairy, Boadwine said.

“We have done a lot of things around sustainability and environmental stewardship just in an effort to survive,” Boadwine said. “We’re just trying to do the right thing, whether it’s from working on things with soils to proper nutrient management. So this, for us, is the next step.”

Turning wastes into energy

Manure is a natural byproduct of livestock operations that must be handled with care as it carries the potential for environmental damage but also serves as a valuable form of fertilizer for crops.

The three dairy farms operated by Boadwine produce roughly 55.6 million gallons of waste combined each year.

The manure is pumped from the barns into large holding lagoons before it is distributed as fertilizer onto nearby farm fields once or twice a year. The process is regulated and monitored by the state Department of Environment and Natural Resources. But one of the problems with the system is that as the manure sits in the storage lagoons, it creates methane that escapes into the atmosphere.

In the spring or summer of 2020, Brightmark Energy will begin building a set of large covered tanks known as anaerobic digesters at Boadwine’s farms. Manure will be pumped into the digesters, which are kept as oxygen-free as possible. The result is an ideal environment for microorganisms called methanogens to become active.

As the name suggests, methanogens produce methane as a byproduct of digestion of organic material. Methanogens actually play a key role in the decomposition of almost all organic material. Because they produce so much methane, methanogens are a big reason why landfills and animal agriculture are considered contributors to climate change.

In the closed environment of an anaerobic digester, methane can be captured before it escapes into the atmosphere. Brightmark expects to collect around 217,000 million British Thermal Units worth of renewable gas each year from the digesters on Boadwine’s farms, or roughly enough energy to power 2,411 average U.S. households for a year. The final step in the gas collection process includes filtering and pressurizing the gas to meet pipeline specifications, Powell said.

Boadwine’s farms, meanwhile, get what amounts to royalty payments for hosting the digesters and for providing the raw material needed to create the gas. Neither Boadwine nor Powell was willing to discuss how much the farms would be paid for the use of their manure, though Boadwine noted the financial incentive was only a small part of his decision to work with Brightmark.

The farms also get to keep the nutrient-rich solids left in the digesters after the methanogens have finished their work. Those solids will then be used as fertilizer to grow crops used to feed each dairy’s cattle, Boadwine said.

“It’s a huge circular value to us,” Boadwine said of the gas project. “It’s another way of extracting and using a byproduct out of our waste stream.”

South Dakota’s massive agricultural industry could prove fertile ground for the renewable gas industry. As of October 2019, the state was home to 452 permitted CAFOs, or concentrated animal feeding operations, that were allowed to house up to 9.6 million animals. Of those CAFOs, 47 were dairies housing about 145,000 cows and 142 were hog farms housing about 750,000 animals.

"We have done a lot of things around sustainability and environmental stewardship just in an effort to survive. We're just trying to do the right thing, whether it's from working on things with soils to proper nutrient management. So this, for us, is the next step." -- Lynn Boadwine, South Dakota dairy operator

Renewable gases a growing industry

Collecting usable gas from manure or even food waste isn’t a new idea. European countries in particular have taken a keen interest in what has been dubbed “renewable natural gas,” a market driven by high natural gas prices and the need to avoid importing gas from countries such as Russia. There are more than 4,000 renewable gas capture facilities in Germany, according to the USDA.

Cities in the U.S. have found several ways to profit from harvesting methane from landfills and wastewater treatment facilities. Sioux Falls, for example, has received more than $17 million from a deal to sell methane generated by the city landfill to a POET Biorefining ethanol plant in Chancellor, S.D.

Still, renewable natural gas collection has been slow to catch on in the U.S., in part because natural gas mined thousands of feet below the earth’s surface is cheap and easy to get domestically. The equipment needed to collect and process methane from animal and food waste, meanwhile, can be expensive. Large landfill gas collection projects can cost tens of millions of dollars, said David Cox, director of operations for the national Coalition for Renewable Natural Gas, which advocates for the expansion of renewable gas production.

Powell wouldn’t provide an estimate for what Brightmark expects to spend on the gas collection systems at Boadwine’s farms. Such systems can cost anywhere from $500,000 to $5 million, depending on the operation’s size, according to the USDA national Cooperative Extension Service.

Demand for renewable gas skyrocketed In 2014. That year, the EPA included renewable natural gas on its list of cellulosic biofuels that can be used to meet the federal Renewable Fuel Standard. In 2020, the RFS is set to require that about 20 billion gallons of the nation’s transportation fuel come from renewable sources such as corn ethanol. Renewable natural gas can be used to fuel vehicles such as buses and garbage trucks, Cox said. Today, as much as 95% of the 590-million-gallon cellulosic biofuel production standard is provided by renewable natural gas, Cox said.

State-level efforts to address climate change, such as California’s Low Carbon Fuel Standard, are starting to play a bigger role in renewable gas development, Cox said. Under the California law, utilities and businesses can buy credits from renewable gas producers, such as Brightmark, as long as the gas they produce is injected into an interstate pipeline system that eventually connects to California, Powell said.

California is Brightmark’s biggest market for renewable gas. Customers in California can either pay Brightmark directly for gas out of a pipeline or they can buy credits from Brightmark that will pay for renewable gas production in far flung places such as South Dakota as a way to offset the consumer’s use of fossil-based gas. Brightmark also takes advantage of federal renewable energy tax credits in order to make a profit, Powell said.

One of the biggest advantages of renewable natural gas is that it doesn’t need expensive new infrastructure to be sold to consumers, said Emily O’Connell, director of energy market policy for the American Gas Association. The utility companies that own existing natural gas pipelines actually are looking forward to being able to sell renewable gas to interested customers at a higher rate than traditional natural gas, she said.

Growing demand for renewable gas has left Brightmark and other companies hopeful of expanding their renewable gas footprint in South Dakota. Brightmark is already working with operators of several other dairy and hog CAFOs in an effort to capture more gas, Powell said.

“You have the opportunity to have a project in South Dakota and have folks in the state of California help support farming communities because they value renewable natural gas more than regular natural gas,” Powell said.