KEYSTONE, S.D. – The intensely partisan and politicized national debate over immigration policies has cast a cloud of uncertainty over guest worker programs that for years have helped provide employees to seasonal South Dakota businesses that cannot find enough American workers.

The viability of some businesses in the tourism, agricultural and construction industries are at stake if federal programs that bring foreign workers to South Dakota each summer are not stabilized soon.

With the unemployment rate at 2.8% in South Dakota – one of the lowest rates in the nation – hundreds of businesses and farms cannot hire enough people to get them through the summer tourism, harvest and construction seasons.

Last year, guest worker programs run by the U.S. departments of labor and state brought about 4,400 people from a variety of other countries to South Dakota to take jobs that employers cannot fill with local employees. Most visitors stay about six to 10 months and are paid a fair wage set by the federal government. The majority of guest workers arrive from Mexico, Central America and sometimes South America or Asia on temporary visas granted through the federal H-2A and H-2B seasonal employment programs. Employers provide them housing while the workers build homes and businesses, clean hotel rooms, work in restaurants or help harvest crops.

The program has been highly successful in fulfilling critical staffing needs at businesses around the country; about 66,000 visas are granted nationally under the H-2B program each year, and 134,400 H-2A visas were granted in 2016. Sioux Falls, which had a 2.4% unemployment rate in February, was the South Dakota city with the most H2-B visas granted in 2018 with 346, followed by Custer and Arlington. Sioux Falls also led the state with 447 H-1B professional visas issued in 2018.

But staunch partisanship in Congress and a strong stance against illegal immigration by the Trump Administration have hampered efforts to reform, strengthen and streamline guest worker programs. Uncertainty over getting workers, delays in when promised workers arrive and logistical issues have reduced the effectiveness of some guest worker programs.

A resort owner in the Black Hills couldn’t open her business on schedule and is turning away reservations. One South Dakota dairy operator is unable to get guest workers to keep his operation running efficiently year-round. And a Mitchell concrete company owner refuses to apply for guest workers after a bad experience with the H-2B program.

Members of the South Dakota congressional delegation are working to cut through the partisanship, educate colleagues on the need for guest workers and improve the logistics and stability of the programs. But several recent reform efforts have been stymied by congressional gridlock and a reluctance by the Trump Administration to prioritize improvement of legal immigration programs that aid states like South Dakota.

“It’s been several years in a row that we’ve had this challenge,” U.S. Sen. Mike Rounds, a South Dakota Republican, said in an interview with News Watch. “We’d sure like to get it back to where it was a stable program and one in which people recognized the need for it and understood that this is a legal visa system that actually works and that it is not part of the illegal immigration problem.”

Losing money every day

In a typical April, Dani Banks would already be making money by providing housing to the tourists who visit Mount Rushmore and the Black Hills.

Banks operates the Holy Smoke Resort, a seasonal Keystone business with 26 full-service cabins and 21 sites for recreational vehicles that is usually open from April to October.

Due to delays in getting workers under the H-2B visa program, Banks has been unable to open the resort and is losing money every day.

“We’ll get open almost a month late this year,” she said. “I’m not open because I can’t get my cabins ready to go with just me and one employee.”

For nearly two decades, Banks has used the H-2B visa program to hire up to five housekeepers from Mexico who live in RVs on her property and keep her cabins clean and ready to rent. This year, if they come, they will be paid $10.55 an hour, a wage set by the government.

Banks has had success with the H-B2 program, but in recent years she has been anxious due to uncertainty over if and when she will get guest workers. The situation worsened a couple years ago when Congress changed the rules regarding returning workers, making it more difficult to bring back the honest, steady crew of housekeepers she has come to trust and rely upon.

“Those employees are critical and we can’t run our businesses like this every year,” Banks said. “You just can’t do it.”

Like other South Dakota employers who use guest worker programs, Banks needs foreign workers because locals aren’t interested in the jobs she has open each summer.

In order to qualify to get guest workers, Banks spends about $2,500 per employee before they begin work to pay for visa and broker fees, travel costs and to advertise for open jobs in a local newspaper and online.

In 16 years of advertising locally for housekeepers, Banks said only two people have applied. One didn’t show up for the interview and the other was arrested on drug charges during the hiring process.

With uncertainty hovering over the H-2B program and the lottery-based system of connecting employers with workers, Banks expects it will only get tougher to run her business at a profit. She has already turned down some reservation requests this year.

“It’s been really awful, and this is no way to run a business,” she said. “At one point, we stopped taking reservations for the summer last year, and pretty doggone quick, we’re going to have to close off units this year.”

Banks and others who use the H-2 visa programs say they have never had a problem with guest workers leaving their work assignments or violating the terms of their visas in order to say in the country illegally.

Temporary, non-immigrant guest worker programs run by the U.S. Department of Labor and U.S. Department of State provided about 4,400 workers to South Dakota employers in 2018, according to federal data. The J-1, Exchange Visitor Program brought 1,517 temporary workers to the state in 2018. That year, 1,414 workers came on H-2B temporary non-agricultural visas, 863 arrived on H-2A temporary agricultural visas, 599 on H-1B temporary professional visas and 61 on permanent visas.

While the guest worker programs provide employers with some help in creating a stable workforce, they do not come close to filling the needs of employers who face worker shortages amid historically low unemployment rates.

Data from the federal Bureau of Labor Statistics show that South Dakota was tied for the fifth-lowest unemployment rate in the nation at 2.8% in March, tied with Hawaii and Nebraska and behind the Great Plains states of North Dakota (tied for lowest at 2.3%) and Iowa (2.4%.) The national unemployment rate in March was 3.8%.

The low rate means people in the state’s overall workforce of 464,200 typically have several options when it comes to finding a job.

In many cases, the industries that obtain workers through guest worker programs tend to be in fields that don’t pay well or include job duties that may not be desirable to local workers.

In 2018, the top five industries seeking workers under the H-2B visa program were for construction laborers, cement masons and concrete finishers, maids and housekeepers, landscape workers and food preparation employees.

The top five applications for H-2A agricultural visas in 2018 were for equipment operators, construction of livestock buildings, grain workers, beekeeping and livestock handling.

Guest workers critical to agriculture

Tom Peterson, director of the South Dakota Dairy Producers, said some agricultural industries that run at full speed all year long are unable to benefit fully from guest worker programs that place a time limit on the visas.

While some dairy operators participate in the H-2A visa program, it doesn’t provide them with as much help as it could, Peterson said.

“It’s the only avenue, so some must utilize it, but in terms of securing a labor force, it’s really a challenge for them,” Peterson said. “The biggest challenge now is establishing continuity and having a workforce you can count on and know that it’s going to be there long term.”

Peterson said the intensity and partisanship in the ongoing immigration debate in Congress and the U.S. as a whole has hampered efforts to incorporate meaningful reform of guest worker programs that could aid South Dakota producers.

Peterson pointed to the omnibus immigration reform bill put forth in early 2018 by House Judiciary Committee Chairman Bob Goodlatte of Virginia that, among other things, would have expanded the guest worker visa program for the dairy and the meatpacking industries. The bill sought solutions for many hot-button immigration issues, including providing amnesty for some children of immigrants born in the U.S., expanding security at the border and cracking down on sanctuary cities.

But the compromise bill fizzled, and the expanded guest worker program for dairies went down with it.

“It’s such a hot political issue that they gained some traction and then last summer, that in essence was killed,” Peterson said. “It’s hard to find an answer to such politicized issues.”

Republican U.S. Sen. John Thune of South Dakota introduced a measure earlier this year to grant 2,500 more H-2B visas to states with unemployment rates of 3.5% or lower.

“This is a time-sensitive matter for employers in South Dakota to ensure they can secure temporary, supplemental workers to help with their operations,” Thune said in an email to News Watch. “Without the extra labor, businesses can’t run at full capacity, and some may face challenges opening at all.”

So far, Thune’s bill has not been acted upon.

Progress has also stalled on a congressional effort to grant H-2B visas to 30,000 more guest workers this fiscal year. More than 90,000 employers applied to get more workers under that proposal, but the effort has stalled due to delays created by the recent resignation of former Homeland Security Secretary Kirstjen Nielsen, Rounds said.

The Department of Homeland Security plays a critical role in vetting potential visa holders and in administering the visa program. In his email to News Watch, Sen. Thune said he is seeking a long-term legislative solution to fix problems with the H-2 visa programs and to remove some authority from the homeland security agency.

Rounds said fixing any problems in the guest worker programs has been slowed by the Trump Administration, which he said has not put a priority on dealing with visa and legal immigration programs.

“This could work a lot smoother than what it does, but it will require the administration to do that in a more timely basis,” Rounds said. “And while we authorize it, we can’t make them do it, we can direct them to do it, but they still have to actually execute it, and if it’s not a priority for them, it makes it more difficult to get it done on time.”

Lynn Boadwine is a prominent dairy farmer from Baltic who often struggles to find enough qualified workers. Over the years, Boadwine said he has had success with the H-2A guest worker visa program and the use of immigrant labor in general.

Boadwine has about 3,200 milking cows in two separate operations and also runs a farm.

The H-2A program helps Boadwine get workers for his seasonal “go time” on the farm, a stretch in the summer where he needs help pumping manure, harvesting alfalfa, managing his hay fields and cleaning hundreds of fans that keep his cows cool.

Boadwine is anticipating the arrival of seven to 10 H-2A guest workers in May who will make about $14 an hour and be allowed to stay until December.

Boadwine advertises locally for open positions at the dairy but doesn’t have much success.

“There’s not a lot of U.S.-based employees that want to milk cows for a living,” he said. “In our dairies, we milk 24 hours a day, seven days a week. It’s hard work, it’s rapid paced, and when we put out an advertisement, we don’t have a lot of people that are interested in doing that kind of work.”

But current immigration rules prevent him from obtaining guest workers for his dairy operations because existing visa programs do not allow for stays beyond one year. Of the roughly 134,400 H-2A visas granted in 2016, the average stay in the U.S. was for seven months.

Boadwine supports reform of guest worker programs to aid producers whose operations run at full speed all year long. “Somebody in Congress needs to change the rules to remove seasonality or the temporary nature of it,” he said.

Boadwine uses migrant workers in his dairy who are not affiliated with any guest worker program. In doing so, he has gained a deep respect for their work ethic and an appreciation of the cultural diversity they add to his operation.

Boadwine said he once loaned $6,000 to a Guatemalan employee who wanted to buy a corn grinder to open a tortilla shop in his home country. The man paid the money back in five months, Boadwine said.

“I can’t tell you the respect I have for a lot of these migrant workers,” he said. “A lot of them are just good people that are trying to make a better way for their family.”

Boadwine said he supports enforcement of immigration laws and strengthening of America’s border. He believes it’s possible to crack down on illegal immigration while also supporting efforts to bring eager, qualified guest workers to the United States.

“There’s nothing wrong with strong borders, and there’s nothing wrong with a functional guest worker program,” he said. “But because of this polarization we have, we haven’t reached consensus and it’s difficult for politicians to deal with, and as a result, nothing changes.”

Mixed results for SD employers

For some South Dakota employers, the paperwork, expense and government regulation over the guest worker programs aren’t worth the effort.

Mike Bathke, owner of Big Dog Concrete in Mitchell, said he is almost constantly in need of qualified workers. “I was going to straight up quit the construction business because I couldn’t get any help,” Bathke said.

A few years ago, Bathke said he tried to alleviate his staffing shortage by entering the H-2B visa program. He paid up-front money to a broker to begin the process of bringing foreign workers to Mitchell, and he even bought and furnished a home to provide housing for the workers.

But when he missed out on that year’s visa lottery and was told no workers would be coming, he was turned off from the program for good.

“If I have to go that route again, I’ll be straight up honest with you, I will have an auction and sell all my equipment and get out of the business,” Bathke said. “I don’t like the government telling me how to run my business or how much I have to pay my employees.”

Bathke said he and other construction employers have a hard time finding local employees who are willing to work up to 70 hours a week pouring foundations, laying basements and finishing floors. Business is booming and at this point, with the crew he has, Bathke said he doesn’t have to seek out new contracts.

Bathke, who pays up to $19 an hour and provides full benefits, said he has about 10 employees who are from the local area but also employs four or five Hispanics who have papers to work in the United States but are not part of a visa program.

He said the word gets out among foreign workers that he pays well and provides benefits, so he is able to find non-local employees fairly easily to fill open positions. He said his foreign employees, who often don’t speak English well, are excellent employees.

“The Hispanic population has been phenomenal to me,” he said. “They’re good workers, very loyal, show up every day and don’t complain.”

The potential for a prosperous high season has dimmed for some employers in Keystone, the small town at the foothills of Mount Rushmore National Memorial, which drew about 2.3 million visitors in 2017.

“I’ve heard a lot of fear and concern over not being able to staff for the summer because of problems with the visa programs,” said Richard Greene, president of the Keystone Chamber of Commerce and manager of the Rushmore Express hotel. “We have 500 or more jobs open and we have a town of only 325 people, so a lot of the businesses really rely on bringing in that summer help.”

Greene said the 190 members of the Keystone chamber share resources when possible to fill jobs during the high season. For example, hotel operators who bring in guest workers under the H-2B visa or J-1 exchange program may pay those workers in the morning and then release them to work in restaurants that need employees in the evenings.

Greene has used J-1 workers at his hotel but does not find the H-2B program workable because of logistical challenges and concerns that visas won’t be available to workers who apply.

“We’ve tried to get them, but we’ve had a lot of issues in the past when they couldn’t get their visas,” he said. “Part of the problem is that we would love to hire people, but if they can’t get their visas for whatever reason, it makes it difficult for us and for them.”

Greene said H-2B workers also can’t stay long enough to get him through the spring and fall tourism “shoulder” seasons.

A lack of stability in the H-2B program. Greene said, puts a burden on employers, the locals who work for them and on customers. During the summer high season, occupancy at the 84-room hotel a half-mile from Mount Rushmore can reach 95 percent.

“If you don’t get the workers, you end up working extra hard and sometimes you don’t get to do what you want,” he said. “If you have projects or things you were planning to do workwise, you have to put those on hold because you’re the only guy here who’s sometimes cleaning rooms and sometimes checking people in at the front desk.”

Just around the corner in Keystone, David Holmgren has found great success with the J-1 Exchange Visitor Program run by the State Department that brings college students to the United States to work and travel.

In partnership with his husband Jesus Roman, Holmgren owns and operates a Subway restaurant in Hill City and a Subway, Dairy Queen and the Holy Terror Coffee & Fudge shop in Keystone.

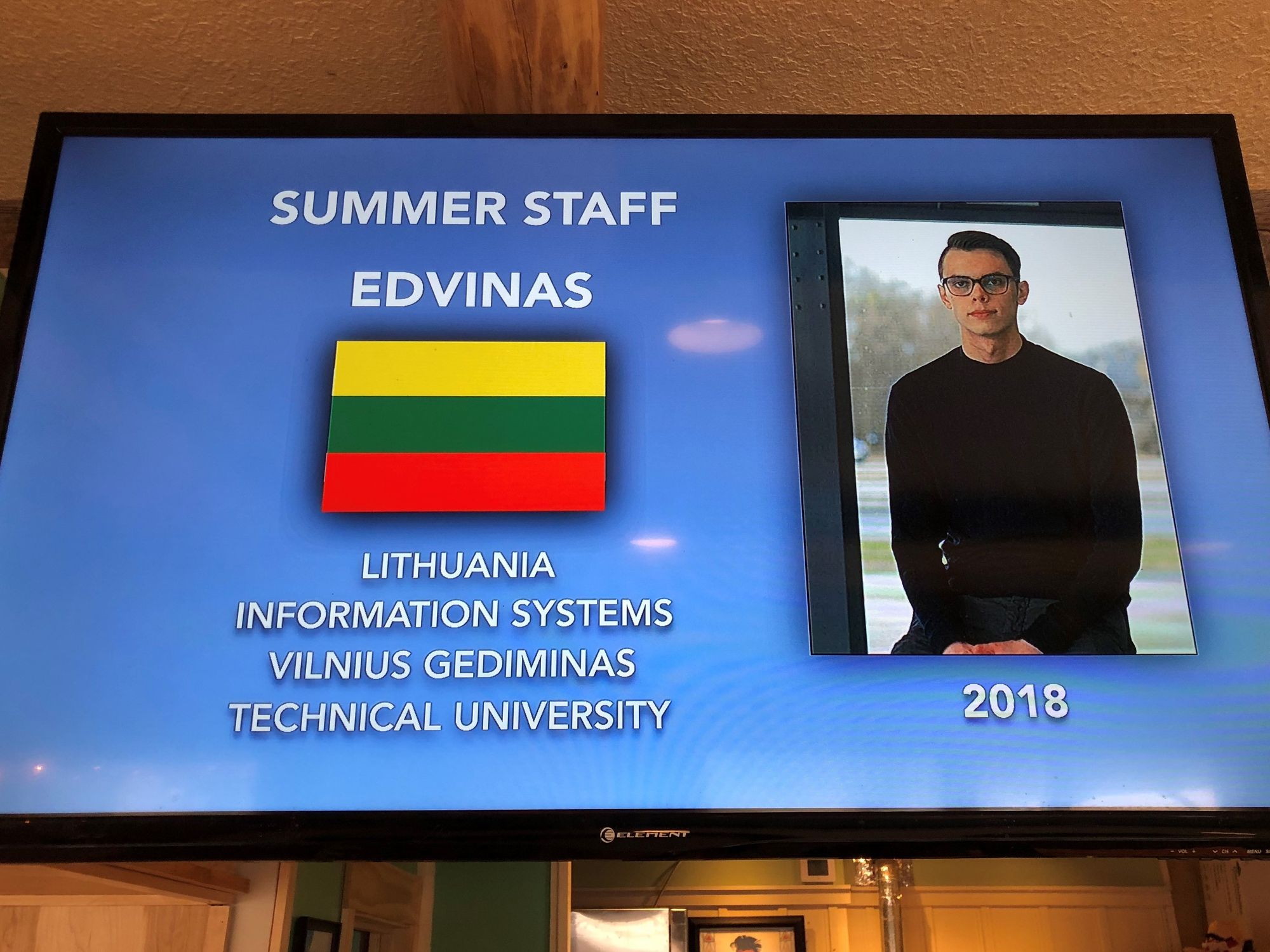

Holmgren has only two full-time employees, so he relies extensively on the J-1 non-immigrant Work & Travel program to provide him with employees during the high season. This year, Holmgren is hosting about 35 student workers under the program, and he promotes their presence on video screens in his restaurants that show a photo and give some background on the guest workers. About 265 of the J-1 participants will work in Keystone this summer, he said.

“There is no simple answer to this complex issue of seasonal employment, but it’s very clear if we lose support of this resource in South Dakota, we will see small service retail and industry fail,” Holmgren said.