A recent court ruling that found South Dakota violated federal voting registration laws has reignited the long-standing concern over Native American ballot access as the state braces for a 2022 gubernatorial election that could hinge on Indian Country precincts.

In a state with nearly 78,000 Indigenous residents, comprising 8.8% of the population, advocates of greater Native enfranchisement have worked to enlist new voters in areas such as the Pine Ridge and Rosebud reservations that lean left-of-center politically.

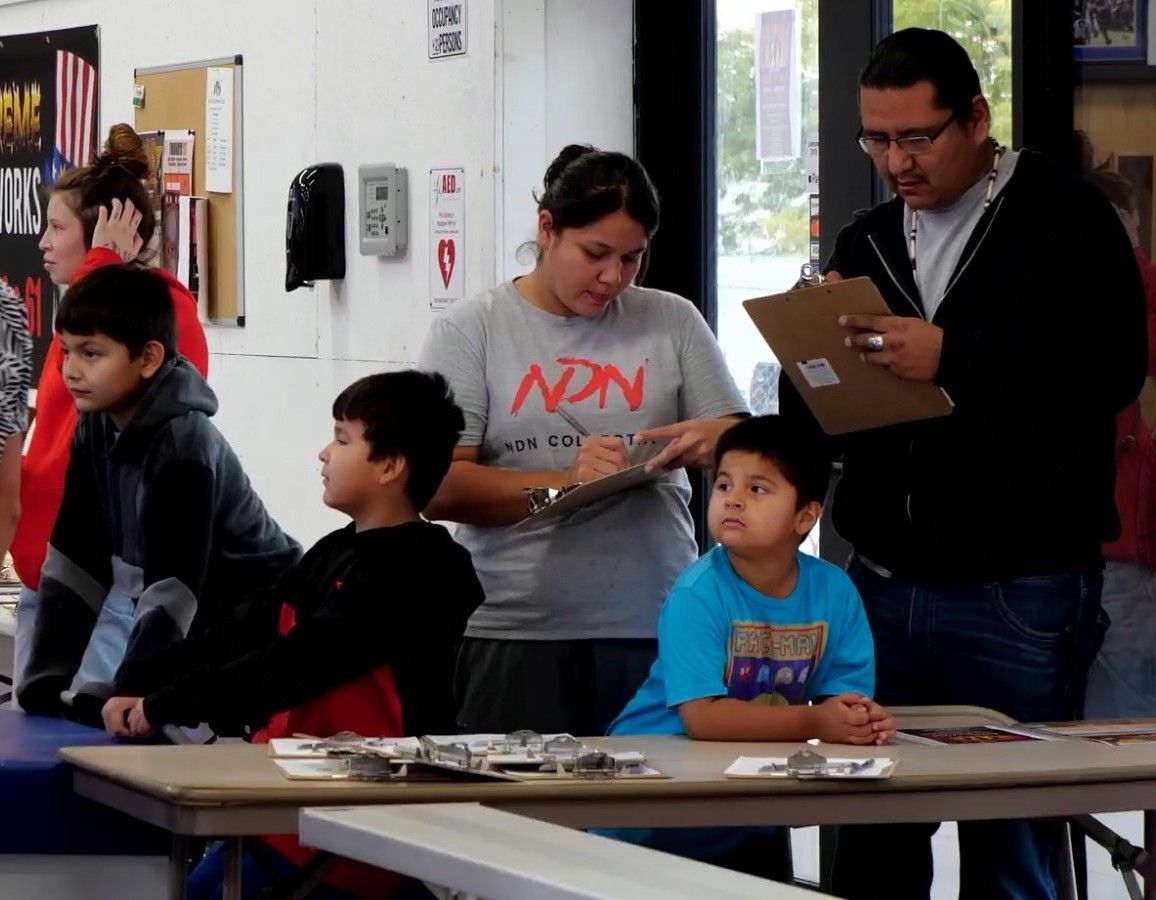

“If we start voting, we’re going to be respected,” said Chase Iron Eyes of the Lakota People’s Law Project, whose group held an Oceti Vote Fest in Rapid City on Oct. 22-23 featuring a basketball tournament and concert, with staffers on hand to help people with registration forms. “If we don’t vote, we don’t matter.”

These efforts come as Republican Gov. Kristi Noem seeks re-election Nov. 8 against Democratic challenger Jamie Smith, a race that a South Dakota State University poll conducted in late September and early October showed as within the margin of error.

It’s also a time of increased focus on voting rights and election security, partly influenced by former president Donald Trump’s refusal to concede the 2020 election despite no evidence of widespread electoral fraud. Heavily Democratic counties such as Oglala Lakota (home of the Pine Ridge reservation) and Todd (home to the Rosebud reservation) can loom large in close statewide elections and voting practices there have also been scrutinized by supporters of the Republican-dominated status quo.

South Dakota Secretary of State Steve Barnett pointed to a tug-of-war between making it easy for eligible citizens to vote while ensuring that nobody tries to subvert the system through the absentee ballot or voter registration process.

Nationally, 34% of voting-age American Indians and Alaska Natives are not registered to vote, compared with 26.5% of non-Hispanic whites, according to the U.S. Census Bureau. Low turnout is also a concern: Oglala Lakota (41%) and Todd (55%) lagged well behind the statewide turnout of 74% for the 2020 general election.

Reasons for Indigenous non-participation in elections range from cultural and language barriers to socioeconomic realities and geographical challenges, such as long driving distances to the nearest polling site. For many reservation residents, the registration and voting process is complicated by not having a traditional street address, home mail delivery or broadband.

Barnett noted that there are several absentee voting satellite sites in reservation communities such as Eagle Butte, Wanblee and Mission, the result of legal battles between Native advocacy groups and past secretaries of state. Lawsuits have been filed accusing state officials of ignoring federal voting rights laws and in some cases pushing for more restrictive policies that disproportionately affect minority or low-income residents.

In May of 2022, a federal judge agreed with the Rosebud Sioux and Oglala Sioux tribes that South Dakota had violated portions of the National Voter Registration Act (NVRA), which was signed by President Bill Clinton in 1993 and took effect in 1995. The law requires state officials to provide voter registration information and guidance to eligible voters when they renew their driver’s license at the Department of Motor Vehicles or when receiving public assistance (such as food stamps or Medicaid) at the Department of Social Services and other state agencies.

In representing the tribes, the Native American Rights Fund produced data showing that the amount of voter registration applications processed through South Dakota public assistance agencies decreased by 57% from 2004 to 2018, from 7,000 applications down to 2,981. The lawsuit also accused Department of Public Safety officials of not properly transmitting voter registration forms to county auditors in some cases.

“It was not a priority, to say the least, and the extent to which it was not a priority suggests a level of voter suppression,” said Samantha Kelty, a Washington D.C.-based attorney with the Native American Rights Fund.

Judge Lawrence Piersol granted a summary judgment saying the tribes had “supported their claims of improper implementation of the NVRA by the Secretary of State, Department of Public Safety, and Department of Social Services,” adding that Barnett as the chief elections officer “contributed to these failings through inadequate training and oversight.”

As part of the settlement reached in September 2022, Barnett said his office designated Suzanne Wetz as state NVRA coordinator to oversee the training and oversight process, which includes public reporting of voter registration data. The state has also changed the wording on driver’s license applications so that the form requires a person to opt out of the voter registration process, rather than require them to opt in.

Barnett said he has had to remind legislators during session that state laws running counter to federal provisions put the state at risk of lawsuits such as the one brought by the Oglala and Rosebud tribes. Lyman County was ordered by a federal judge in August of 2022 to work with the Lower Brule Sioux Tribe to change the county commission election process, which used an at-large system that denied representation by diluting the vote of the county’s 38% Native population.

“We play a lot of defense during session, basically telling legislators, ‘Pass all the state laws you want, but make sure they comply (with the NVRA),’” said Barnett, who was defeated for the 2022 GOP nomination by Monae Johnson. “Our goal is to provide reasonable access and make it hard to cheat, but it’s tough to please everybody. It would be nice to take the politics out of it.”

That’s hard to do when the Native American vote has been instrumental in races such as Democrat Tim Johnson’s U.S. Senate win over then-Congressman John Thune in 2002, the result of registration drives and get-out-the-vote efforts in reservation counties.

Supporters of greater ballot access insist that giving all citizens an opportunity to engage in the democratic process is not a partisan endeavor.

“We don’t care how Native Americans vote, we just want them to be able to vote, and we work across the country to make that happen,” said Kelty. “Native Americans are not a monolith. Every tribe is different, and every individual is different.”

Reservation vote helps elect a senator

In the early-morning hours of Nov. 6, 2002, with results of his Senate race against Thune too close to call, Tim Johnson went to bed.

“It was sort of that classic Norwegian stereotype where he said, ‘There’s nothing I can do about it now – I might as well get some sleep,’” Drey Samuelson, Johnson’s longtime chief of staff, told News Watch. “I wasn’t quite so calm. I think I slept for about five minutes in my chair.”

Samuelson knew things were going to be tight. Johnson, a Vermillion-raised Democrat elected to the Senate in 1996, was fending off a challenge from the fast-rising Republican Thune, with internal polls the week of the election showing Johnson up by less than a percentage point.

At campaign headquarters in Sioux Falls on election night, some staffers shed tears as Thune held a lead for much of the night. But Samuelson knew that late returns from Shannon County (now Oglala Lakota County) could push his boss over the top.

“We worked the reservations really hard and were winning the Native vote by about 90 to 95% across the state,” Samuelson said. “I knew how many votes were still out there from Pine Ridge and figured we would win about the same percentage (among Native voters) that we had won elsewhere. While everyone else was freaking out, I was saying, ‘I think we’re going to win this thing.’”

The final tallies from Oglala Lakota County, traditionally among the last to report because it lacks an administrative center and has ballots processed in adjacent Fall River County, showed that Johnson won 92% of the county vote, giving him a statewide winning margin of 524 votes when the counting finally ended around 9 a.m.

The groundwork was laid long before the election, as grassroots organizer O.J. Semans and his Four Directions advocacy group focused on voter registration drives on the reservation. Oglala Lakota registration totals jumped 50% from 2000 to 2004 (5,338 to 7,984) while Todd County rose 44% (3,923 to 5,664) during that period.

Thune conceded the race about a week after the election and opted not to seek a recount, saying such a process would be “painful for the state.” Other state Republicans pointed to potentially fraudulent activity surrounding absentee ballot applications and the payment of “bounty hunters” to register people on the reservation. Those allegations led to two prosecutions and one conviction – a Rapid City man who said he was paid by the United Sioux Tribes while on work release from the Pennington County Jail to fill out voter registration cards, something he and his friends did by copying names from the phone book. He pleaded guilty to possession of a forged instrument and was sentenced to six months in jail.

Mark Barnett, the state attorney general at the time, dismissed many of the fraud allegations as politically motivated. Asked by the Rapid City Journal in 2004 about complaints that Democrats were keeping track of voter rolls to determine who needed to be brought to the polls, Barnett said: “That’s not a crime. That’s a lesson plan.”

The narrative of Johnson’s 2002 triumph being fueled by Native turnout provided leverage for Indigenous voters. Thune made numerous trips to reservations during his 2004 Senate race against Democratic Minority Leader Tom Daschle, modestly increasing his vote percentage in Oglala Lakota County from 8% in 2002 to 13% in defeating Daschle in 2004.

One of the most significant breakthroughs came from Republican George S. Mickelson, who received 21% of the Oglala Lakota County vote when first elected governor in 1986. Mickelson won the county with 59% four years later after making reconciliation with the state’s Indigenous community one of the hallmarks of his administration.

Registering Native voters still a challenge

Jamie Smith has made several trips to Oglala Lakota County during his campaign, including an Oct. 11 reservation swing through Pine Ridge, Porcupine and Kyle with state legislators Red Dawn Foster and Peri Pourier.

Gov. Noem’s spokesperson, Ian Fury, didn’t respond to a request for information about Native outreach efforts made during her re-election campaign. In Noem’s 2018 race against Democrat Billie Sutton, she received just 214 votes (7%) in Oglala Lakota County, the lowest percentage for a major-party gubernatorial candidate in the county in at least 40 years.

Noem, who vowed to prioritize Native relations during her campaign for governor, alienated Indigenous leaders while in office by cracking down on potential Keystone XL pipeline protests, leading the Oglala Sioux Tribal Council to temporarily ban her from the Pine Ridge Reservation.

Relations worsened in the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic, when the governor engaged in a legal standoff with tribal officials over their use of roadside checkpoints to try to control the spread of the coronavirus on reservations.

“If you were on Pine Ridge at the time, you would have seen 1,000 people from traditional warrior societies arm themselves to the teeth and to go to every checkpoint to make sure that our territorial integrity was not violated,” said Iron Eyes, who ran unsuccessfully for a North Dakota U.S. House seat as a Democrat in 2016, garnering 24% of the vote.

The battleground has shifted in many respects to conflicts over the rights of Native residents to be counted, quite literally in the case of the 2020 census survey. The U.S. Census Bureau estimates that Native Americans living on reservations were undercounted by 5.6% nationally, continuing a trend from 2010, when the estimate was 4.9%. Census data helps determine formulas for funding distribution, legislative districts and policy decisions.

Many states used federal COVID funds to promote awareness of the census and help reach hard-to-count populations during the pandemic. South Dakota did not, despite an estimated 1.4% statewide undercount in 2010. Noem was criticized by tribal officials for waiting until September of 2020 to form a statewide Complete Count Committee with outreach to Native communities, just weeks before the deadline to respond to the census survey.

“South Dakota could very easily be a leader in championing Native American voting rights across the board, and that’s not happening,” Kelty said.