A group of business leaders and volunteers with almost no journalism training or experience has banded together to launch a local weekly newspaper in Kingsbury County, S.D., where two weekly papers were closed on April 1 due in part to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Armed only with an untested business model and promises of help from unpaid volunteers — but steeled by a passion for their communities and a commitment to keeping people informed — the group plans to launch its new newspaper on May 20.

The effort to replace the De Smet News and Lake Preston Times, which closed due to financial losses on April 1 after more than a century in operation, originated within the economic development corporations in the two towns.

Board members with the De Smet and Lake Preston development corporations were aware of the financial hardships facing American newspapers, and knew that Dale Blegen, longtime owner of the two weekly papers, was looking to retire and sell his businesses. Blegen and owners of other small newspapers were facing slow declines in circulation but even greater losses of advertising revenues amid the pandemic.

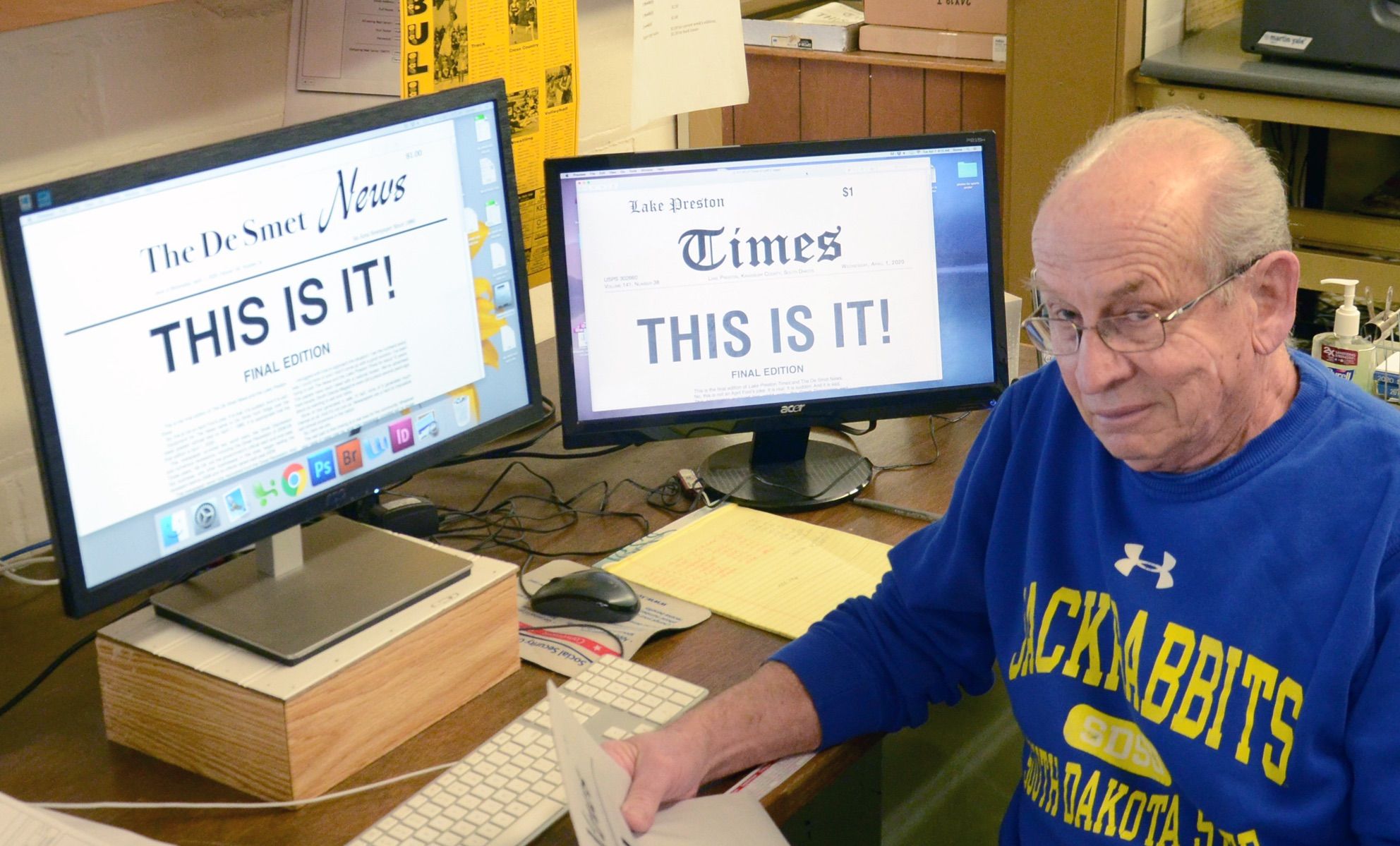

Still, on April 1, when Blegen published his farewell editions that announced the papers were closing, many locals were shocked, and the closures immediately left a hole in the fabric of the two communities in east-central South Dakota.

“At first there was a feeling of loss, of something missing that we had to some degree taken for granted,” said Tim Aughenbaugh, a De Smet business owner who is on the board of the local development corporation. “The more we began to think about it, we realized what an important role a newspaper plays in a community.”

The first step was to buy the businesses from Blegen, who published the De Smet paper for 43 years and the Lake Preston publication for 36 years. The development corporations bought the newspapers’ brick buildings in the two towns for a combined $65,000, which Blegen said also included ownership of the two newspapers. The sale is not final but a contract is signed, Blegen said.

The group then put out a survey on Facebook to get public input, which overwhelmingly indicated that, despite years of sporting and civic rivalry between De Smet and Lake Preston, the group should combine the two papers into one countywide paper. The new name will be the Kingsbury Journal.

“Certainty a lot of us are learning as we go ... but we have a broad skill set here, which I think will benefit us. I do think the pluses will outweigh the minuses.” -- De Smet businessman Tim Aughenbaugh, who is spearheading the launch of a new weekly newspaper in Kingsbury County

Aughenbaugh began an analysis of the former newspapers’ finances, their business models, methods of production and distribution and the content. He produced a 35-minute YouTube video that explains in clear language why a local newspaper is needed, how it might be possible to produce it, and how it could be financially viable.

“As it turns out … it is a much more complex and challenging operation under the hood,” Aughenbaugh narrates in the video. “You quickly begin to realize that running a newspaper is like running on a treadmill that never stops.”

The financial analysis looked closely at expenses and revenues and showed that during good times, the income from subscriptions, legal notices and advertising would allow for a small profit after printing, production and payroll costs were paid. But in recent months, with businesses closed and advertising in the tank, Blegen said he was losing about $2,000 a week under the former business model.

Aughenbaugh concluded that the only way to make the equation work was to eliminate or drastically reduce employee costs. That meant relying almost exclusively on unpaid volunteers from the community to write articles, take photos, design the website and the paper, and get the printed copies distributed around the county. So far, none of the paid staff members from the former papers, including Blegen, is formally involved in the project, Aughenbaugh said.

Word of mouth and a social media campaign led to formation of a cadre of about 15 volunteers who have agreed to pool their talents and energies to gather news and produce and distribute the paper.

“We’re learning as we go; certainty a lot of us are learning as we go,” Aughenbaugh said. “But I’ve been surprised by how many people have some kind of background in journalism who have come out of the woodwork.”

That includes a man who did graphic design and layout at his college paper, a woman who spent several years as a sales manager at the Los Angeles Times, and Katlin Johnson, whose mother, Jeanne Limoges, served as the editor of the Sioux Valley News in Canton, S.D., while Johnson was young.

“The smell of the ink, I still remember that,” said Johnson, 31, who also worked on her high school yearbook. “Growing up, my mom would edit my school papers; not just read them, but edit them.”

Johnson, a mother of two who is the administrator of the Good Samaritan Society nursing home in De Smet, said she is not certain what role she will play in helping put out the new paper, but expects she will help shepherd through the content of the first few issues.

“I’m excited to be helping getting it going again, and I’m willing to help out any way I can,” Johnson said. “Maybe we can bring a fresh start and some fresh ideas, too.”

Aughenbaugh said the group has enlisted the help of a design firm that will not only help create the finished product but also provide training to volunteers, including in the basic principles of community journalism.

Aughenbaugh said at this early stage, he is not too worried about maintaining objectivity or running into problems regarding conflicts of interest or libel, though those topics will be addressed in volunteer training.

The new contributors will not be paid for their work, at least at first, Aughenbaugh said. Their work output will be tallied, however, and if the paper begins to turn a profit, the volunteers will become what Aughenbaugh refers to as “paid volunteers” who receive some level of compensation. Once established, the business could also be transferred to an individual or group that would sign a lease agreement to run the paper, not unlike how golf courses or country clubs lease out their dining operations to private operators.

Though the future is undefined at this point, the future is also wide open in terms of what the paper becomes and what content it provides. Aughenbaugh expects that the staff will cover local meetings, take photos of school sports and events, and update readers on the business community. The first edition will also include a historical piece on the contributions that Blegen made to the two communities, he said.

The community-supported, mostly volunteer business model is not without successful precedent in American journalism.

In 2009, a group of concerned citizens in Carbondale, Colo., launched a nonprofit weekly paper after the established for-profit weekly, the Valley Journal, shut down.

The new paper, the Sopris Sun, now distributes about 3,500 free copies at 80 locations in the ski-resort region of central Colorado each week. The paper hired a full-time, paid editor at the outset and now has about three full-time-equivalent paid employees and about a dozen paid freelancers, said Editor Will Grandbois.

“It was very touch-and-go initially; the initial push had a lot more volunteer labor than paid labor,” Grandbois said.

The Sopris Sun is now funded about 80% by advertising and the rest from donations from supporters, including a bequest from a late local resident whose donation has helped the paper remain viable during the COVID-19 pandemic, Grandbois said. The Sopris Sun just won several awards in the Colorado state newspaper contest, he noted.

Aughenbaugh called Grandbois while doing research before moving forward with the plan to launch a newspaper in Kingsbury County.

“I told him that it’s possible, but that it’s not easy,” Grandbois said. “It’s an uphill battle and a labor of love.”

Grandbois emphasized that getting the paper up and running and maintaining it afterward will require support from community members to buy the paper, read it and advertise in it.

“It requires a community to get behind it; it’s not something that happens in a vacuum, and you really need people to want it,” he said. “But if that happens, it can be a beautiful thing, and you’ll know you’re meeting a real need in your community.”

Blegen, 76, now entrenched in retirement, said he was pleased to learn that the community was rallying to produce a new paper, and said that he has provided guidance when asked. He is hopeful that the new business model will provide the financial stability he was unable to secure in the final months of publishing the two papers.

“I think they needed a new model, and this very well may be the new model,” Blegen said. “I don’t think any of these people have any experience or very much experience in the field, but they’re going to give it a whirl.”

Aughenbaugh said the new paper will take advantage of advanced technology, including use of the cloud and working remotely, and will be digitally focused and delivered on mobile devices in addition to the printed version.

Aughenbaugh said he is cautiously confident that the volunteer team can put out a paper that engages, informs and entertains the community.

“This is certainly an experiment for us and we have a lot of challenges in front of us,” he said. “But we have a broad skill set here, which I think will benefit us. I do think the pluses will outweigh the minuses.”