Tooth decay, gum disease and many other oral-health illnesses are considered to be 100% preventable, yet many children and adults across South Dakota continue to suffer severe dental problems.

A lack of access to proper dental care in South Dakota is driven both by geography and income. With a relatively small population spread out across a large area, many South Dakota residents do not have ready access to a dentist. Meanwhile, a high level of poverty in rural, urban and reservation communities also inhibits the ability of both adults and children to obtain proper dental care.

The look of rotting or missing teeth and deep red gums can lead to isolation and ostracism, a lack of employment and educational opportunities and even increased likelihood of generational poverty for those who suffer from severe dental problems.

Increasingly, moreover, poor dental health is known to cause or be connected to numerous other serious health issues, including some that are life-threatening. The Mayo Clinic recently published a report called “Oral health: A window to your overall health,” which links bacteria associated with tooth decay and gum disease to heart illnesses, including clogged arteries, stroke and endocarditis, an infection of the inner linings of the heart.

Links have also been established between poor oral health and premature birth and low birth weight, diabetes and pneumonia.

State and dental-association officials have long focused on educating people on the benefits of maintaining good oral health, and report that some progress has been made in terms of getting more adults and children to see a dentist at least once a year. Programs have been enacted to encourage dentists to practice in underserved areas, and charitable efforts to provide oral care to poor people in South Dakota have expanded.

And yet, many in the dental field are disappointed that improvement in dental health in general and particularly among low-income people has stagnated.

“I don’t know that we’re seeing oral health overall improving,” said Paul Knecht, director of the South Dakota Dental Association. “You’d think that after hammering away at this thing for a couple of decades you would see light at the end of the tunnel, but the rates of decay haven’t changed significantly in the last ten years or so.”

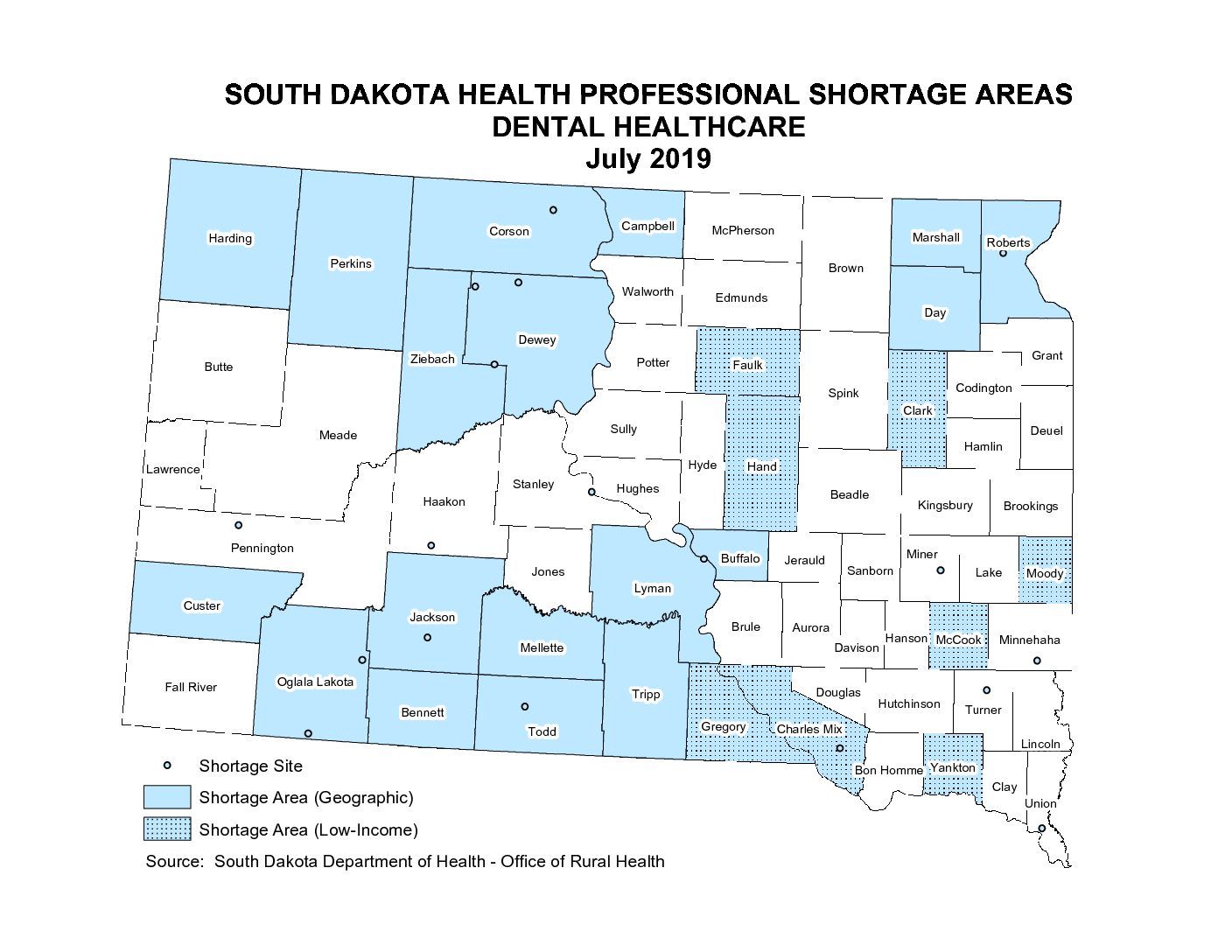

The sprawling nature of South Dakota and a shortage of dentists overall is certainly one factor. In South Dakota, 40% of counties — 26 of 66 — are considered by the state to have a shortage of dental-health services either because of geography or residents’ low income.

Poverty is a major inhibitor of proper dental care in a state where 12.8% of residents, about 110,000 people, live below the federal poverty line, and nearly a third of residents fall within the federal definition of “low income.”

Poor dental health is a significant and vexing issue on the state’s Native American reservations, where limited access to dental care is exacerbated by high levels of poverty.

Problems also exist in the few metro areas of South Dakota, where many low-income residents find it hard to afford dental care or find subsidized care.

“The stories related to poor oral health exist in every corner of the state,” said Mike Mueller, communications manager for Delta Dental of South Dakota, a major dental insurer and provider of charitable care. “It’s everywhere; issues with access to good oral-health care exist across South Dakota.”

Reservations are ‘ground zero’ for SD dental issues

Marty Jones is the office manager and a dental hygienist at the St. Francis Mission Dental Clinic in Todd County on the Rosebud Indian Reservation. Jones calls her clientele “ground zero” for the dental-health problems that afflict many people living in poverty in South Dakota.

The south-central South Dakota reservation has about 12,000 tribal residents and thousands more non-Natives, yet very few dentists or dental services. Native residents can obtain care at Indian Health Services facilities, but access can be difficult and IHS dentists are quick to extract rather than treat teeth with cavities, due to expediency, said Jones, who worked for 13 years at an IHS dental clinic.

Both Native and non-Native residents often rely on the mission clinic to obtain subsidized dental services that range the gamut from prevention to extractions to surgery, Jones said. The clinic does not have a full-time dentist, and receives no state or federal funding, but rather relies on donations and grants for operating costs and relies almost exclusively on volunteer dentists from South Dakota and across the country to go beyond the basic care and education that Jones and one other clinic employee can provide.

Jones said the rate of serious dental problems among her clientele is severe.

“It’s dire straits down here; there’s epidemic proportions of dental caries or dental disease here,” Jones said. “It’s really sad. You cannot even fathom some of the things that we see come through this door, just gross.”

The clinic in 2013 had a registered clientele of about 2,000 people, of which 90% had significant dental problems, Jones said. The situation has only worsened since then. In just the first nine months of this year, the clinic logged 300,000 dental treatment needs that had not been met. Several patients suffer from rotten teeth, gum disease and more serious bone issues all at once, Jones said.

She said the Native and non-Native populations on and around the reservation have difficulty obtaining dental care due to a shortage of providers and several factors related to high rates of poverty and unemployment, including inability to pay, a lack of insurance, transportation challenges and sometimes a multi-generational failure to understand the importance of dental care and the potential health consequences when it is neglected.

Food deserts and a lack of money for healthful food leads to consumption of high-carb diets that create sugars that quickly erode tooth enamel, she said.

Children on the reservation sometimes suffer severe decay and almost complete tooth loss before they are old enough for school, Jones said.

“These kids are losing their teeth at a very young age; from age two to five they’re extracting teeth,” she said. “These kids go weeks or months with toothaches before they can be seen someplace.”

Individual stories of severe dental decay are heartbreaking, Jones said. She tells of one beautiful young Native girl who excelled in school and had a college scholarship but faced the daunting challenge of having almost no healthy teeth. Jones refers to some patient’s mouths as being “bombed out” by severe decay and showing only an “apple’s core,” Jones’ term for a mouth left with no front teeth and only diseased gums showing.

“She was a smart, beautiful girl, but how can she go to a university setting beyond here and have any confidence when the rest of that population does not have that level of decay in their mouth?” Jones said.

Jones arranged for the girl to get help and a dentist was able to bring her mouth back to relative normalcy. Jones said she frequently sees mission clients break down in tears when they get dental care and begin to smile again or even feel comfortable going out in public. Jones said some people see Natives with rotten teeth and mistakenly assume they are addicted to methamphetamine, which can severely damage teeth.

The St. Francis Mission Dental Clinic is hosting volunteer dentists from Connecticut and Rhode Island in the coming weeks, but after that will not have a dentist on site from November until March, Jones said.

Some progress but challenges remain

Despite these problems, state health and dental-association officials say there has been some improvement in access to dental care in the state.

Department of Health Epidemiologist Josh Clayton said recent statewide surveys have shown an increase in the number of adults and children who have had a dentist visit in a 12-month period, and that South Dakota has an overall dental-visit rate that is higher than the national average.

In 2016, phone surveys done as part of the biennial Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System showed that 70.3% of adults had visited a dentist in the past year, compared to the national average of 66.4%. For children ages 1-17 in South Dakota, 88% reported visiting a dentist in the past year, up from 85% in in 2011.

Clayton added that the survey showed that statewide in 2015-17, about 85% of children were covered by some type of public or private dental insurance, compared with only 76% covered in 2011-13. The rate of emergency-room visits for dental or oral-health issues has also dropped in recent years, Clayton said.

“I think we’re doing better than the national average overall, but I think we still have room for improvement because of the importance of oral health, not just on whether a person will have dental caries or cavities, but because the mouth does play an important role in overall health,” Clayton said.

Multiple research studies and anecdotal information from those on the front lines of dentistry in South Dakota have shown a strong correlation between income and access to dental care.

Medicaid and Children’s Health Insurance Program, or CHIP, are the two main avenues for low-income residents to obtain subsidized health care, including dental services. Native Americans can receive subsidized dental treatment at Indian Health Service hospitals.

The American Dental Association Health Policy Institute said in a 2016 study that only half of American children on Medicaid or CHIP had a dental visit in the past year, compared to 67% of children on private insurance. That study, “Main Barriers to Getting Needed Dental All Relate to Affordability,” revealed that, in all, 15.2% of Americans, roughly 48 million people, said they needed dental care but did not get it during the past year.

The top reasons cited for not obtaining dental care were “could not afford the cost,” “insurance did not cover procedures,” and “did not want to spend the money.” The study said that more than a quarter of all working adults in America do not receive dental benefits.

Another ADA study showed that cost barriers were the most likely factor inhibiting someone’s ability to get dental care, as compared with obtaining any other type of health care, including prescription drugs, medical care, eye care and even mental health services.

Knecht, of the state dental association, which has about 410 active members, said that about 70% of dentists statewide accept Medicaid, among the highest acceptance rates in the nation.

Knecht said that although South Dakota dentists generally do a good job of treating low-income people, challenges remain. Despite efforts to expand access, he said, many low-income adults and children may still face significant hurdles in getting good oral-health care, either owing to wide-open geography or low Medicaid payment rates to dentists.

Medicaid payment rates are set and shared by federal and state governments, including in South Dakota, which has among the lowest Medicaid-provider reimbursement rate in the nation.

This situation can lead some Medicaid patients to struggle to get care, he said, especially in rural regions where there are few if any dentists to begin with.

“For the folks in the greatest need, our experience is that things are actually improving, but that we are basically swimming upstream,” Knecht said. “We are challenged because we’re in a very conservative, low-tax environment where the program itself does not pay very well, so we have a lot of dentists who will limit the number of patients they will see, or maybe they won’t take Medicaid patients at all.”

Research by the Health Policy Institute within the American Dental Association highlights the difficulty of getting subsidized dental care in rural areas of South Dakota.

In South Dakota, a third of children under public insurance plans do not live within 15 minutes of a dentist who accepts Medicaid. South Dakota is tied with North Dakota for worst in the Great Plains region at 32% of children in that category, compared with 21% of children in Montana isolated from Medicaid dental services, 16% in Wyoming, 7% in Iowa and Minnesota and only 6% in Nebraska.

Charitable efforts chip away at access issues

Multiple efforts are underway in South Dakota to help improve access to dental care.

For the past 15 years, the Delta Dental Mobile Program and its two dental offices on wheels have provided more than $21 million worth of dental care to about 40,000 patients in more than 80 communities, including tribal reservations.

The trucks and dentists that provide preventive, diagnostic and restorative care travel about 40 weeks out of the year. No patient is denied care because he or she cannot pay.

The mobile dentistry program is perhaps the most visible effort to aid low-income South Dakotans with their dental care by the foundation that is the charitable arm of the nonprofit Delta Dental Insurance Company.

The foundation also supports a loan-repayment program for dentists who agree to treat a certain number of patients on Medicaid, and a program that trains other medical professionals to identify dental issues that may require treatment. The state has a tuition reimbursement program for dentists who agree to practice in underserved areas for three years; since 2012, that program has placed dentists in 10 rural communities.

Delta also teams up with the South Dakota Dental Association to fund the Donated Dental Services Program that provides free dental care to children, adults and senior citizens who cannot afford it. Last year, the program provided $675,000 in care to about 158 patients. Due to the extensive need for services, the program typically has a long waiting list in some locations, Knecht said. The SDADA also provides scholarships and supports dental-health educational programs.

Income no barrier to one Sioux Falls dentist

Some dentists in South Dakota are highly attuned to the challenges facing some parents and children in their desire to obtain adequate dental care.

Jaclyn Schuler is a dentist at the Dakota Dental practice on West 37th Street in Sioux Falls who has accepted patients on Medicaid for more than a dozen years.

Schuler said the great need for subsidized dental care in Sioux Falls is evidenced by the fact that her office receives about five to seven calls per day from people who want to know if the practice takes Medicaid. As one of only three dentists in the office, Schuler said she never turns away a child or a disabled person who is on Medicaid, but must limit the number of adults on Medicaid she treats because the program pays only about 60% of the typical cost of dental care.

Providing subsidized care is somewhat of a calling for Schuler, who said many people are unable to understand the challenges and stresses faced by people in poverty.

“It’s different than the stress we think of, which is work stress or homework stress or whatever,” Schuler said. “These people have real stress; the stress of not knowing where they’re going to get their next meal from, let alone how they can get to their child to the dentist.”

Schuler recalled one mother whose 3-year-old daughter had “a mouthful of decay” and needed dental surgery, but she relied on buses that didn’t run early enough in the day to make her appointments. In response, Schuler said her office paid for a car service to get the mother and child to their doctor’s office.

As for why such a young girl had rotten teeth, Schuler said some families become trapped in a generational cycle of poverty that reduces their ability to properly prioritize dental care.

“A lot of these patients are growing up in a family where their grandma had her teeth removed when she was very, very young, and the mother had her teeth removed when she was very, very young, so it’s just not something that they’ve learned,” Schuler said. “So, to make that active effort to seek out information and care is a bigger challenge than we realize. Their stress is unique to poverty, and we as human beings have the ability to only cope with so many things, so they don’t have the ability or the energy to put their child’s dental care or dental health as a priority.”

Schuler said she understands why some dentists do not accept Medicaid patients, but she added that for her and others in her office, the reduced payment rates are worth the positive outcomes they see for patients who have few or no other options for care.

“You get paid less, but in some ways, you get paid more,” she said.