The extent to which national political movements sway South Dakota’s legislative priorities was rarely more evident than during a House Education Committee hearing in Pierre in early February 2022.

On the agenda was House Bill 1337, one of several education measures brought by Gov. Kristi Noem to keep critical race theory and “inherently divisive concepts” out of state classrooms, in this case by shielding elementary and secondary students from “political indoctrination” through race-based history, social science and civics.

After remarks by Allen Cambon, one of Noem’s senior policy advisors, committee members heard remotely from Stanley Kurtz, a conservative commentator and senior fellow at the Ethics and Public Policy Center in Washington D.C. Kurtz was well-positioned to testify because much of the bill directly matched language from “The Partisanship Out of Civics Act,” model legislation he drafted in early 2021 to help Republican-led statehouses fight against public schools becoming what he termed “playthings of the Left.”

Kurtz’s list of divisive ideas to be banned included the notion that slavery and racism “are anything other than deviations from the authentic founding principles of the United States,” as well as any race-based concept that makes someone feel “discomfort, guilt, anguish, or any other form of psychological distress on account of their (race, ethnicity or religion).”

Those representing the interests of South Dakota public schools during the legislative hearing had pressing questions that were never fully answered: Why was a national political blueprint being thrust upon a state that had not documented local concerns about race-based curriculum? And why had Noem’s office consulted with a national arbiter of right-wing political strategy while neglecting to speak with school officials in her own state?

Kurtz declined an interview request for this story, and Noem spokesperson Ian Fury didn’t respond to a request for details about policy discussions between Kurtz and the governor’s office.

For Diana Miller, a former South Dakota Education Association president who now lobbies for school districts, the lack of communication fit a pattern during Noem’s tenure of making decisions regarding education without consulting local stakeholders, including teachers, principals and administrators.

“I worked with former governors Janklow, Rounds and Daugaard,” Miller said. “Back then, people in the governor’s office called us and asked about things. They asked for input and talked to superintendents. That isn’t happening now, and I don’t understand why.”

HB 1337, South Dakota’s political indoctrination bill, mirrored the wording in legislation banning CRT and action civics in states such as Texas, Louisiana, New Hampshire, Tennessee and Missouri. The Republican legislator who brought the bill in Texas said he conferred with Kurtz in crafting the measure, which becomes law in that state Sept. 1.

The South Dakota bill was killed in the Senate Education Committee by a vote of 4-3. Noem followed with an April 5 executive order that contained much the same prohibitions against critical race theory, stressing that students should learn “America’s true, honest history” and banning divisive concepts in classroom teaching and state standards.

Education officials are not sure how that order will be enforced, but they’re concerned about a “chilling effect” in which teachers are hesitant to discuss important historical topics – such as the Indian Removal Act or Japanese internment camps in America during World War II – for fear of backlash from a student or parent.

“It puts teachers in a difficult place,” said Sandi Hurst, who taught history at Memorial Middle School in Sioux Falls from when it opened in 1995 until her retirement last year. “The wording is so ambiguous that it could set teachers up for possible action if parents or students disagree with what’s being taught.”

“I worked with former governors Janklow, Rounds and Daugaard ... back then, people in the governor’s office called us and asked about things. They asked for input and talked to superintendents. That isn’t happening now, and I don’t understand why.” -- Diana Miller, S.D. schools lobbyist

Passing the conservative test

Critical race theory, typically taught at the university graduate school level, is an academic theory that suggests race is a social construction and that systemic racism is still part of America’s laws and policies. Action civics is an alternative form of civics education in which students explore issues in their community and explore advocacy strategies.

The fact that Noem was influenced by Kurtz on these matters was not surprising. The first-term governor has worked to craft a profile as potential national candidate, courting conservative media as part of the plan. In Kurtz’s view, though, she didn’t always walk the walk. When the state’s Department of Education supported social studies standards last year that Kurtz viewed as left-leaning, he blasted Noem for losing out to “hard-left activists” and questioned her conservative credentials in the National Review, an influential publication that boasts 25 million monthly page views.

“We desperately need alternative models for history and civics education, and Noem is well-placed to create one,” Kurtz wrote. “To do so, however, she’ll need to go beyond showy gestures and govern as the bold conservative she claims to be.”

That essay ran Sept. 20, 2021. The same day, Noem instructed the Department of Education to delay changes to the state’s social studies standards for up to one year to allow for more public input. She went on to change the complexion of the standards committee to align ideologically with anti-CRT sentiment, enlisting a retired professor Will Morrisey from Hillsdale College, a Michigan-based conservative liberal arts institution, to help screen potential members.

Noem’s office also began preparing anti-indoctrination bills for the 2022 legislative session, using Kurtz’s template and inviting him to testify at hearings, where he warned against “the promotion of the idea that we are to be judged first and foremost” by racial or ethnic identity.

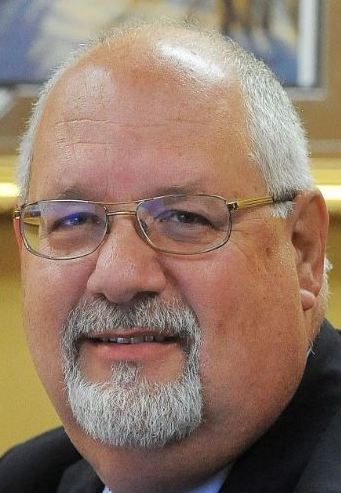

To education officials such as Jim Holbeck, a former Harrisburg School District superintendent who works for the Associated School Boards of South Dakota, it seemed like a coordinated attempt by partisan outsiders to control state curriculum rather than relying on local school boards, administrators and teachers.

“That’s the playbook now – you change what’s going on in the states and you can change the country,” said Holbeck. “So what do we do? Do we change curriculum every time there’s a new election? Do we write Republican curriculum and teach that and four years later write a Democratic curriculum? I mean, seriously. We’re going to mess kids up.”

Noem was the first governor to sign a “Save Our Schools” pledge tied to the Trump-formed 1776 Commission, chaired by Hillsdale president Larry Arnn. He later boasted during a speech that Noem had offered to “build us an entire campus in South Dakota” until Arnn reminded her that Hillsdale relies on donors to maintain its independence from state and federal funding, partly to avoid affirmative action compliance or Title IX requirements.

This was not the first time South Dakota has seen national cultural politics make its way to Pierre, where a Republican supermajority presents fertile ground for such efforts. But many of those following the hearings were struck by a disconnect between ideological bill language and educational priorities such as state funding and retention of teachers.

Asked by a committee member which school districts were consulted in crafting the legislation, Cambon first neglected to answer the question and later said such conversations were “off the record” and the school officials couldn’t be named.

“The first question we always ask is, ‘Where is this happening in South Dakota schools?’ And nobody ever answers us,” said Miller. “That’s why I’m leery of model legislation, because one size doesn’t fit everyone. We’re not Texas. We’re not Florida. We’re South Dakotans. We know our communities and we know our schools. Nobody is indoctrinating kids. If you want to know what’s happening, just talk to the people involved. Nothing is a secret.”

"What do we do? Do we change curriculum every time there’s a new election? Do we write Republican curriculum and teach that and four years later write a Democratic curriculum? I mean, seriously. We’re going to mess kids up.” – Jim Holbeck, Associated School Boards of South Dakota

Controversy surrounds privilege test

The most prominent example of CRT-related instruction cited in Pierre was a “privilege aptitude test” handed out by an English teacher at Sioux Falls Lincoln High School in the fall of 2020. The document was designed to illustrate how some groups enjoy societal advantages that others do not. A student complained about the worksheet to his father, who later met with administrators.

Rep. Sue Peterson, a Sioux Falls Republican, noted this classroom conflict in her support of HR 1337, handing out a copy of the privilege test to committee members.

“There’s no CRT textbook,” Peterson, who declined to comment for this article, said at a House hearing. “You don’t hear the instructor say, ‘I’m going to teach critical race theory.’ It’s the concepts that get embedded, and we’re trying to prevent the promotion of that. We don’t want things like racism promoted.”

The Lincoln High teacher, who was not identified, received a “verbal reprimand” after meeting with administrators, according to Sam Nelson, who lobbies for the Sioux Falls School District. “There was a discussion of what should and should not be taught and the problem was resolved,” Nelson said at the hearing.

There was no follow-up in the state Legislature of what the privilege test was meant to teach or where it came from. Democratic House member Erin Healy of Sioux Falls noted that it’s important to urge students to “think critically about our problematic past and how it shapes society today.”

The worksheet in question originated from the website of the National Civil Rights Museum in Memphis, which is located at the former Lorraine Motel, where civil rights leader Martin Luther King Jr. was killed in 1968. The museum’s website provides educators and parents “online resources for teaching the struggle for freedom and justice to students.”

The privilege test includes prompts such as: When I go to the store, people do not look at me and think I may steal something. I have not or will never be teased about my name. Using public bathrooms and going from floor to floor is not difficult for me. When I contact or look at the politicians and people who represent me in government, they will most likely look like me.

Though students are asked to keep a tally or yes and no answers, the accompanying text emphasizes that the test is “not intended to grade but to serve as an aid to understanding the topic of rights and privileges.” Some of that context was missing from the handout at Lincoln High and other schools around the country, leading some students to believe they were being graded on their scores.

Noelle Trent, director of education at the National Civil Rights Museum, told News Watch that the privilege test has been removed from the museum’s website because of negative backlash in some instances that overshadowed the benefits of the material.

“Whenever you do these sorts of exercises, what is critical is context,” said Trent, who has helped curate historical projects for the National Park Service and Smithsonian Institution. “The (privilege tests) were never meant for someone to do without accompanying reading, videos or classroom discussion. It’s meant to be part of a broader training.”

Asked about the Sioux Falls teacher handing it out to students without providing background or resources on subjects such as the Civil Rights Act of 1964, she said: “That is not sound pedagogy, just handing out a test to students and saying, ‘Look at how privileged you are.’ That can cause harm, especially to marginalized groups. Sound pedagogy is placing it in the proper context around race and other socioeconomic and geographic factors.”

Working toward understanding

Similar lessons were learned four years ago in Oconomowoc, Wis., a predominantly white community of 15,000 residents located 35 miles west of Milwaukee. In January of 2018, the high school recognized Martin Luther King Jr. Day with a school-wide assembly and homeroom activities that included the privilege aptitude test.

A series of parental complaints to the school board and a conservative radio station led the board to limit discussions about social privilege except “in classrooms where it is related to a specific course and teachers could provide appropriate context.” The board also called for better communication with parents who might want to opt their child out of future activities involving sensitive topics.

“There were parents who said their kids weren’t really prepared for the discussion about privilege,” said Amanda Hart, a parent of children in the Oconomowoc district who criticized the board’s decision to limit diversity discussions. “[The students who complained] didn’t have the baseline understanding and felt targeted as peers by students who disagreed with them.”

Hart started a Change.org petition that urged community members to “stand up for the values of diversity and inclusion.” Her goal was to get 100 signatures but the petition ended up with more than 2,000, sparking community conversation about the specific goals and limits of race-based curriculum.

“A lot of people associate talking about race in school with CRT, but those are not the same things,” said Hart, who has two children in elementary school and one in high school. “In some respects, in order to be more open in schools, we need to educate the parents. The burden can’t all be on the educators.”

The debate led the school board to organize a community session to discuss topics such as social privilege and unconscious bias eight months after the MLK Day furor, headed by a college professor. More than 50 Oconomowoc residents showed up for a 2-hour meeting that included lecture slides and group activities, according to the Milwaukee Journal Sentinel.

“One of the things we talked about tonight is having common language,” Roger Rindo, the superintendent at the time, told those in attendance. “Communities don’t have to have common agreement, but they need to have common understanding. Thank you for helping us work toward some of that.”

‘How do you measure discomfort?’

Holbeck, the former Harrisburg superintendent, was teaching a workshop for aspiring administrators last month when he decided to try something new, based on discussions that had occurred within the state Legislature.

“I told them that their assignment was to answer the question, ‘What is critical race theory?’” Holbeck recalled. “The first person said, ‘I don’t know.’ The next one said, ‘I’m not sure.’ I got through eight people, and none of them had the definition. I said, ‘Do you see the problem here? We’re hearing so much about this CRT and how we’re not supposed to teach it, and we don’t even know what it is.”

Much of the language from Kurtz and others to characterize divisive classroom concepts comes from a national doctrine touting academic freedom from “woke” ideology. Supporters call it pushback to the social justice movement stemming from George Floyd’s murder at the hands of Minneapolis police in 2020 and initiatives such as the New York Times “1619 Project,” which according to its editors sought to “reframe the country’s history by placing the consequences of slavery and the contributions of Black Americans at the very center of the United States’ national narrative.”

Rep. Peterson distributed a document to fellow legislators called “Responding to Social Justice Rhetoric: A Cheat Sheet for Policy Makers.” The material came from the Oregon Association of Scholars, whose president, Portland State University professor Bruce Gilley, wrote a controversial 2019 essay entitled, “Was it Good Fortune to be Enslaved by the British Empire?” which featured the line: “To be black in America is, historically speaking, to have hit the jackpot.”

The cheat sheet, to which Peterson referred in her remarks, characterizes social justice as “a denial of just rewards to those who follow the law” and systemic racism as “an attempt to dismantle freedoms and to forcibly redistribute public and private goods.” Rep. Bethany Soye, a Sioux Falls Republican, added to the discussion by calling CRT a “worldview that divides everyone into the oppressor or the oppressed depending on the color of your skin.”

The only classroom example presented other than the privilege test was an “MTV Decoded” video shown to a class at Sioux Falls Roosevelt that sparked a complaint from a parent, who said it made her son “feel guilty for being white.” The video, first released in 2016, talks about race as a social construct and cites a Housing and Urban Development study showing that Black and Latino renters are shown 12 percent fewer units on average than white renters.

Nelson, representing the school district, pointed out that it was an Advanced Placement human geography course in which the students can achieve college credits. He also noted that teachers are already bound by a National Education Association code of ethics that prevents disparagement or unequal treatment of students based on race, ethnicity, sexual orientation or political or religious beliefs.

“I get nervous when we start talking about subjective concepts that are going to impede education,” said Nelson.

Part of the problem, said Holbeck, comes from viewing education through the prism of a white, Christian frame of reference. This has been a point of contention for Native American educators who protested the last-minute removal of references to the Oceti Sakowin Essential Understandings from a draft of state social studies standards last fall.

In communities with significant Native populations and in school districts such as Sioux Falls, where more than a quarter of students are Black or Hispanic, banning race-based history curriculum that makes some students uncomfortable becomes a matter of perspective. Trent, from the National Civil Rights Museum, has seen this play out in various state legislatures and is concerned about the raw reality of America’s racial history being softened or suppressed.

“My family’s story should not be overlooked because it makes some people uncomfortable,” said Trent. “Most history is hard. We want these hard stories to be told to show that all that has been overcome and what challenges are still present.”

Wade Pogany, executive director at Associated School Boards of South Dakota, posed the classroom hypothetical of “To Kill a Mockingbird,” Harper Lee’s Pulitzer Prize-winning 1960 novel about a white lawyer who represents a Black man unjustly accused of rape in a small town in 1930s Alabama, a staple of high school literature classes across the country.

“If I’m the teacher and I come to you as an administrator, can I teach that book?” Pogany asked during a committee hearing. “It deals with racism, discrimination, bullying. What if the students are uncomfortable with that and it causes them discomfort or anguish? How do you measure discomfort? We don’t know our parameters. In the final analysis, laws should give us direction, laws should be clear, and they should be put in place to solve a problem that actually exists in South Dakota.”