Thousands of people who don’t live in South Dakota have become official residents, gotten registered to vote and then cast ballots in state elections, which some lawmakers and election officials fear could unfairly alter election results or open the door to fraud.

State election officials say they are aware that people are claiming on voter registration forms to live at an address where they do not, but a lack of enforcement of state laws allows it to continue, a South Dakota News Watch investigation has found.

Critics worry that lax state residency requirements and the hands-off approach to voter registration enforcement have heightened the potential for voter fraud and election tampering in South Dakota.

In Pennington County, about 6,300 voters are registered to a single rural address where it is clear no one resides; about 1,400 people are similarly registered to vote from a business address in Hanson County.

Some county auditors say they routinely approve voter registration forms, signed under penalty of perjury by applicants, which they believe contain false information about where the applicant resides. A top election official in the Secretary of State’s Office said she is aware of voter registration discrepancies but has not been enabled by the court or law enforcement to challenge questionable registration applications.

The potential illegality of the voter registration process came to light in the ongoing court case involving incorporation of the town of Buffalo Chip in Meade County. After reviewing the case, a judge wrote a report confirming that a handful of people who claimed residency and registered to vote at the Buffalo Chip campground admitted at a public meeting that they do not live there.

Daniel Ainslie, city manager of Sturgis, which opposes the Buffalo Chip incorporation, said the voter registrations at the campground are evidence of how the current system is flawed and open to fraud.

“This is about voter integrity; we’re talking about people registering to vote in a state or a locale where they do not live,” Ainslie said. “What I’m worried about as a South Dakotan is that this is such a small state that it’s not hard for major parties to go over to Minneapolis or somewhere else and register 5,000 people to vote in South Dakota and flip a state legislative race or congressional election.”

Ainslie said he is shocked that state officials have been unwilling to address the flaws in the voter registration system. “It’s unbelievable to me if we allow that to occur,” he said.

State lawmakers considered a bill to tighten voter registration laws this session, but despite some concerns over potential election fraud, the measure died in its first committee.

Lack of enforcement across the state

Many of the questionable voter registrations result from businesses that allow non-residents, often retirees traveling the country in recreational vehicles, to easily register to vote at the same time they register a vehicle and establish residency in South Dakota. People who register a vehicle and get a driver’s license in South Dakota can establish residency if they have a receipt showing they spent one night in the state. Some mailbox businesses have an RV park or motel rooms on site to make that process easier. The services performed by mail-forwarders all appear to be legal under state law.

Once a person establishes residency, registering to vote only requires filling out and signing a one-page form.

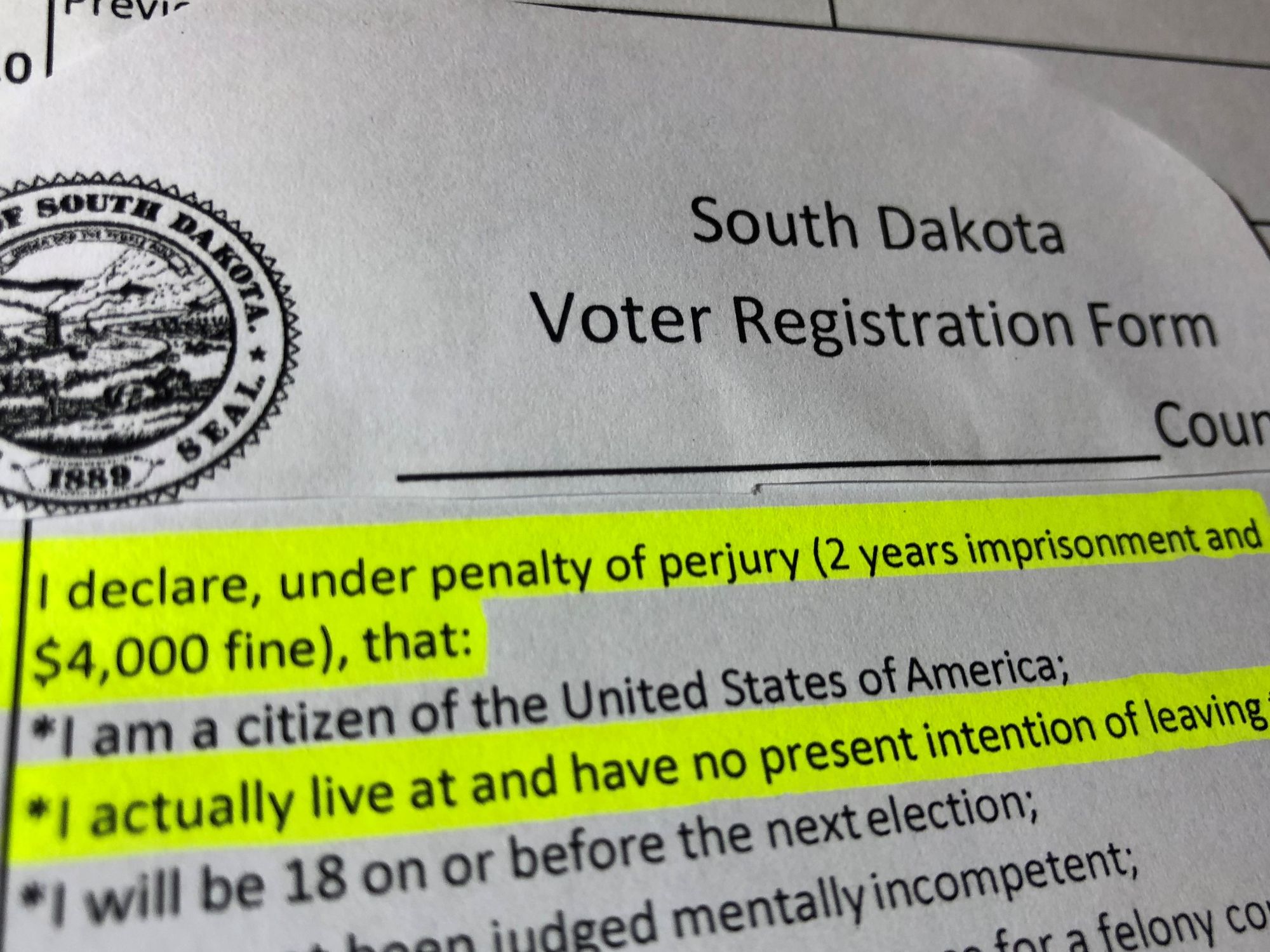

However, the voter registration form requires the signee to affirm that, “I actually live at and have no present intention of leaving the above address.” The form states that an applicant who perjures themselves could face two years in prison and a $4,000 fine.

Pennington County Auditor-elect Cindy Mohler said she and other auditors have been instructed by the state that unless someone formally challenges the registration of a voter, they should continue to approve signed registration forms from any location in the county.

“We don’t police that and we don’t do research on this person to say have they really stayed there,” Mohler said. “We are taking the voter at their word.”

Mohler oversees a voting precinct in Box Elder where more than 6,300 people are registered to vote at the address of a mail forwarding company called Americas Mailbox, located on Americas Way.

“You could use somebody else’s address, whether it’s Americas Way or Cindy Mohler’s backyard,” she said. “When forms come in to our office, we have no way of knowing if you ever stayed. We have no way of proving that.”

A circuit judge who reviewed the Buffalo Chip incorporation case in 2016 was convinced that voter registrations had been improperly filed.

In his findings of fact and law, former Fourth Circuit Judge Jerome Eckrich ruled that voters who registered at lots on the campground site were not living there. “The ‘lots’ referred to in the voter registration form are just raw ground,” Eckrich wrote.

The judge also found that, “No one actually lives at the residence addresses identified on the Meade County Voter Registration forms.”

One address in the East River town of Emery is home to between 1,100 and 1,400 registered South Dakota voters, though none of them live at that location, said Hanson County Auditor Lesa Trabing. The legal voters at that address – home to the mail forwarding business My Home Address – make up roughly three times the total number of residents of Emery, which has a population of about 450.

Those registered voters form the largest voting precinct in the county, making up a third or more of the 3,300 active voters in the county, Trabing said.

All of the voters registered at that address must sign the registration form under the threat of perjury.

Whether they live at that address or not, Trabing said that as long as the paperwork is filled out and signed, she certifies the applicants as legal voters.

“The state knows about this and they say continue to register them,” she said.

Trabing said she does not know of a time the Emery motor-voters had an impact on an election, and added that no one has ever legally challenged their voter registration. She said she knows of several other South Dakota businesses that are registering vehicles and voters.

“These places are popping up all over; it’s a common thing anymore,” Trabing said.

On its website, My Home Address spells out for potential customers the advantages of registering a vehicle and gaining residency in South Dakota.

In a section called “Why South Dakota?” the primary answer is that the state has no personal income tax or personal property tax on vehicles. Further, it states that the one-time excise tax on vehicles is only 4 percent, that there are no vehicle inspections required. Another section notes that South Dakota does not have an inheritance tax.

Other mail forwarding services – such as Dakota Post and Your Best Address in Sioux Falls and Americas Mailbox in Box Elder – provide customers with similar reasons to register vehicles or obtain residency in South Dakota.

In an FAQ tab on the My Home Address webpage, the question, “Do I need to travel to South Dakota to become a resident?” is answered with the statement, “No!!!! You can establish your address and register your vehicle through the mail, but you will need to travel to South Dakota to obtain your driver’s license.” The fees to have mail forwarding and other services at My Home Address start at $150 a year and rise depending on services selected.

Bruce Kjetland, president of My Home Address in Emery, serves on the Hanson County Commission and said he has examined local voter data that he said show his mail-forwarding customers do not have an impact on local elections.

“They don’t vote in school board or county commission races, but some voters will vote in legislative races and for president,” Kjetland said.

My Home Address follows all state laws and does not encourage customers to register to vote when they sign up for mail forwarding, get a driver’s license or establish residency, said Kjetland, a Republican.

“We’re not here pushing that ‘Hey, you better go register to vote and vote Republican,’” Kjetland said. “We just do our job and help the customer do what they want to do.”

Kjetland said his clients are often traveling the country in recreational vehicles and simply need a home base and a place to establish residency. He said the registration fees paid by his clients generate about $450,000 a year in revenues that are split between the state and Hanson County.

“Their domicile is where they’re at because they kind of live all over, but they use South Dakota as their main address,” Kjetland said. “It’s great for South Dakota because they live everywhere but we get the money because they register here.”

Kea Warne, director for the division of elections within the South Dakota Secretary of State’s Office, said she is aware of the risks associated with mail-forwarding services and high levels of non-local voters registering there.

“They could maybe vote in someone different, and that could be an RVer,” she said. “They vote to not let a wheel tax go through, or a bond election. The precinct in Hanson County could change the outcome of that election.”

At this time, there’s no way to know how many people are registered to vote in places they do not live. Other data can help fill out the picture, however.

About 60,000 out-of-state vehicles are registered in South Dakota, according to Wade LaRoche, a spokesman for the state Department of Revenue. Meanwhile, revenues from vehicle title and registration fees have doubled over the past decade, from $88.3 million in 2009 to $176.7 million in 2018, LaRoche said.

Perjury threat doesn’t stop registrations

Warne said her office regularly fields phone calls from people who are registering to vote in South Dakota but get worried when they see the declaration of address and the perjury statement on the registration form.

“We get a lot of calls from RVers and they ask how they can legally sign that voter registration form,” Warne said. “We can’t give them any guidance, but they know they’re signing under penalty of perjury. If they are not living there, they are perjuring themselves with the information they are providing on that form.”

Yet Warne and other elections officials say they do not know of any registration challenges or criminal charges being filed against someone who misrepresents their residency on a voter registration form.

“That’s never been challenge in court, so unless there’s a court ruling challenging it, a county auditor who receives a voter registration and everything is complete and goes through all verification checks, the county auditor has to process that application,” she said.

The Secretary of State’s Office was hoping that the state Supreme Court or the judge in the Buffalo Chip case would rule in a way that gives finality that it is illegal to register to vote at an address a person does not live, though that did not happen, Warne said.

“We were hoping the Supreme Court would say that you can’t just camp one night and register to vote, that either yes, they can come in and camp at the location and register to vote, or else they can’t,” Warne said. “We were hoping we would get a determination on that.”

Election, voter fraud a national concern

Concerns over voter registration policies in South Dakota come as questions about the fairness and sanctity of American elections continue to permeate the national discourse.

Voter fraud and election tampering are at the heart of an ongoing dispute in North Carolina in which the state recently set a new election after allegations that absentee ballots were manipulated to give one candidate an advantage.

In a sparsely populated state like South Dakota, it isn’t hard to find elections where a few fraudulent votes could swing an election. In 2018, seven legislative races were close enough to warrant a recount, and some county races came down to one or just a few votes.

A 2012 report by the Pew Center on the States highlighted serious flaws in the process of accurately and fairly registering voters across the country.

Titled “Inaccurate, Costly and Inefficient,” the study discovered that one in eight voter registrations in the United States, about 24 million, were no longer valid. The study found that 2.75 million people were registered to vote in more than one state, and that 1.8 deceased people were still listed as registered voters.

The report concluded that voter registration methods are outdated and have not kept up with modern technology and are “plagued with errors and inefficiencies that waste taxpayer dollars, undermine voter confidence and fuel partisan disputes over the integrity of our elections.”

One element of the South Dakota registration form authorizes cancellation of voter registration in another area but provides no directions on how to do that or assurances it will take place.

South Dakota also places no time limit on how long someone must stay registered at a specific address, said Sturgis City Attorney Greg Barnier.

That means someone who had a position on issues far from where they live could simply register to vote in that area and cast a ballot there, Barnier said.

“Just the thought that people can start hopping around to vote in Rapid City because they’re interested in the civic center expansion and then vote in Yankton because they’re interested in the pool referendum there,” he said. “There may be people in Meade County who would like to vote in Rapid City to raise taxes to pay for a civic center that could benefit them, and that would be legal.”

Some state lawmakers are aware of the potential for abuse of the South Dakota voter registration system.

Rep. Tom Brunner, R-Nisland, filed House Bill 1129 this session to require that in order to register to vote, a person must actually live in South Dakota. Current law states that a voter must obtain residency 30 days prior to an election, but is somewhat vague on how legal residency is determined.

Existing law related to residency for voter registration states, “the term, residence, means the place in which a person has fixed his or her habitation and to which the person, whenever absent, intends to return.” The “whenever absent, intends to return” language in the law has sometimes been cited by those who don’t believe that a person must live in South Dakota in order to vote here.

Brunner’s bill would strike that language and add stronger language requiring that, “a qualified elector may have only one residence, shown by an actual fixed permanent dwelling, establishment, or any other abode to which the person returns when not called elsewhere for labor or other special or temporary purposes.”

Brunner said he brought the bill after constituents neighboring uninhabited properties grew concerned that the owners of those properties could improperly vote in local elections. He said the language is modeled after a residency law in North Dakota.

“We’ve got some issues where people don’t have a residence and … they’re not an established resident in an area and they’re affecting the vote and outcome of elections,” Brunner told the House State Affairs Committee in early February.

The bill was opposed by Warne, who said the “special or temporary purposes” language was too broad and placed an unwieldy burden on county auditors to interpret what special purposes might be.

The committee voted 10-3 to kill the measure but not before lawmakers, including House Speaker Steven Haugaard, R-Sioux Falls, expressed concerns that South Dakota elections could be subject to fraud if residency changes aren’t made.

“I agree there’s a high potential for some districts, where a handful of votes make a difference, so we need to give this attention very quickly,” Haugaard said, noting that he’s heard of situations where groups of like-minded people were bussed into an area to register to vote in order to unfairly swing an election.

“I know there are abuses that take place in a lot of states. It hasn’t been quite so much here yet, but it’s on the horizon,” said Haugaard, who suggested voter registration would be a suitable topic for a summer legislative study.