Rural ambulance services in South Dakota are having an increasingly hard time recruiting volunteers and generating revenues, putting the stability of the services at risk and making it more likely that rural residents will endure longer response times in emergencies or possibly lose ambulance service altogether.

While most larger cities in South Dakota have professional ambulance services or fire departments with paid staff members, rural services rely mostly on volunteers. In recent years, those rural providers have seen fewer people willing to volunteer and those who do volunteer are older residents who are aging out of the workforce.

About a third of rural ambulance directors in South Dakota said they couldn’t respond to a call because of staffing shortages, according to a 2016 survey. Roughly a third more said response times were delayed due to lack of staffing.

Paying the bills is also a growing challenge for ambulance services, which see limited patient billings and high levels of non-payment write-offs. Patient billing is the main funding source, and it usually does not cover the costs of responding to an emergency or transporting a patient, let alone covering overhead for the service.

Rural ambulance services sometimes do not see the call volume needed to cover costs such as equipment, insurance, training or staff. Budgets are often supplemented by millions of dollars a year in volunteer labor.

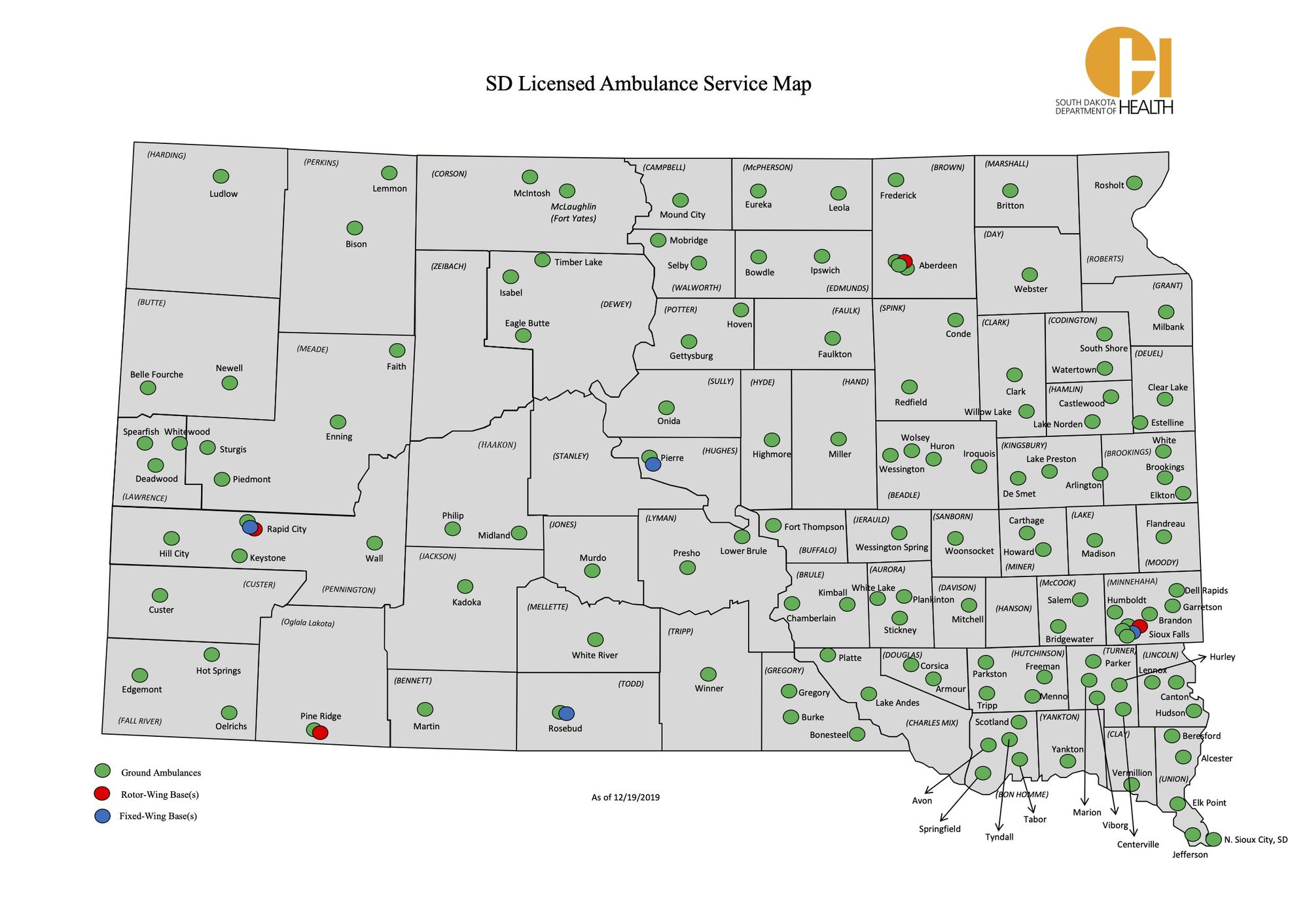

Ninety-five of South Dakota’s 126 ambulance services are staffed with at least some volunteer labor, according to a state-funded survey from SafeTech Solutions. The majority of rural ambulance directors said they think they can function financially for the next five to 10 years, but just one-third were confident they would be able to fully staff a 24/7 service in the future, according to the survey.

To run a 24/7 ambulance service in South Dakota, a provider needs at least 14 workers, yet almost half of the state’s volunteer ambulance services reported having fewer than 10 people on the roster, according to the survey.

The COVID-19 pandemic reduced the dwindling volunteer pool even further. The active EMS workforce decreased by almost 30% in the last year because volunteers worried about contracting the virus, according to the South Dakota Department of Health.

Ambulance volunteers and directors said the decline in volunteerism has been a concern for years. Younger people are moving into more urban areas or don’t want to volunteer for a medical job they think should be a paid position.

“The major concern is that an ambulance will be needed and no one is available, and we will see an increase in morbidity and mortality,” said John Becknell, an analyst for SafeTech Solutions, a consulting firm that studies and provides guidance to emergency medical services. “I’m really concerned because fewer and fewer South Dakotans are bearing the brunt of carrying this load.”

“The major concern is that an ambulance will be needed and no one is available, and we will see an increase in morbidity and mortality.” John Becknell, analyst at SafeTech Solutions

Staffing shortages caused a volunteer ambulance service in rural Meade County to shut down last year, suddenly putting residents of the area an hour of travel time from any ambulance coverage.

The Rural Meade County Ambulance Service in Enning, about 50 miles east of Sturgis, closed in April 2020. The service responded to about 30 calls each year, and volunteers from Enning also assisted other agencies and transported patients in major emergencies.

After the closure, ambulances services in Faith and Newell agreed to cover most of the more than 1,200 square miles previously serviced by the Rural Meade County Ambulance Service. In extreme emergencies, air ambulances can respond to calls in the small swath still considered uncovered by the other ground ambulances.

In a subsequent election, Meade County voters approved a new ambulance tax district last year. Households in the county outside of Sturgis will contribute about $75 a year for the service, and county commissioners agreed to give the Rural Meade County Ambulance $5,000 to re-open. About 10 people are taking the 180-hour class required to become emergency medical technicians. County leaders hope these efforts bring back the service.

The uncertainty in Enning is a possible harbinger of future problems for other rural ambulance services, said Jerry Derr, assistant for the Meade County Commission office.

“What’s happened in central Meade County is going to be replicated statewide,” said Derr, who has had conversations with the South Dakota DOH about the issue. “You’ve got people doing this for decades but want to get out of it, having that responsibility and trying to get younger people in the community and pick up that mantle, you’re just not getting in the rural areas.”

Ambulance services critical to rural areas

Long response times for ambulance services are commonplace in rural South Dakota, and could get worse if rural service providers are unable to stay in operation.

Kathy Chesney and her crew in Philip recently drove 47 miles north of their station to help a patient too weak to get out of his house. While the ambulance team was there, that patient went into cardiac arrest and was saved by the responding EMTs.

The Philip Ambulance Service, located in sparsely populated Haakon County, was the closest to the rancher’s home.

“If we hadn’t been there, he would not have survived,” said Chesney, 55. “Anything else would’ve been too late.”

The Philip Ambulance Service responds to about 230 calls each year in its service area that covers more than 1,200 square miles. About 15 volunteers are on the roster, but only three people are typically available to take calls during the day, said Chesney, who has been a paramedic in the area for 24 years.

The long service distances and response times are more common in West River regions. East River services can sometimes be found 10 miles apart, while services in the western side of the state may cover portions of multiple counties and be located many miles from one another.

A 2017 report on the Sturgis Emergency Ambulance Service said the lack of certified paramedics is “a serious problem in the state and especially west river.”

Nationally, rural ambulance systems are critical to the 60 million people who live in rural America and some services are on the verge of collapse, according to a January report from the Rural Policy Research Institute.

The ambulance service struggles are tied to the continuing closure of rural hospitals across the country, adding to a growing dearth of healthcare in rural areas. Since 2005, 176 rural hospitals have closed nationwide, according to the Rural Policy Research Institute. In the same timeframe, the average transport time to rural hospitals increased from 14 minutes to more than 25 minutes.

Severe trauma patients are most likely to benefit from medical care within the first hour of an injury, and urban patients are three times more likely than rural patients to reach severe trauma care within an hour after a car crash, according to the study.

Emergencies such as skiing accidents or hiker injuries that require crews to ride snowmobiles or hike to an injured person can easily push response times to an hour, said Brian Hambek, director of the Spearfish Emergency Ambulance Service.

South Dakota urges that 90% of all 911 calls lead to a dispatch of help within 10 minutes, Hambek said, though there is no state requirement for service times.

Ambulance services in far western South Dakota sometimes need to transfer patients to Montana or Colorado when closer South Dakota hospitals can’t take a patient, which could put a crew out of service for up to 14 hours. If another emergency occurs in their coverage area while they’re gone, other volunteers or services must be called upon.

States across the country on average decreased state allocations to EMS offices by 10% between 2014 and 2018, according to the Rural Policy Research Institute.

The EMS program within the South Dakota Department of Health Office of Rural Health received about $422,000 from the state general fund, EMS agency licensure fees and EMS professional licensing fees, according to a 2020 report from the National Association of EMS Officials. The state received about $115,000 in federal funding, according to the same report. The health department did not respond to follow-up questions about state funding for EMS and a spokesman said the director for EMS was not available for an interview.

The estimated cost of operating and staffing a single rural ambulance in South Dakota is about $484,000 each year, according to SafeTech Solutions survey. About $384,000 of that is estimated to be volunteer work.

Statewide, that reaches about $30 million in unpaid labor from volunteers each year.

“South Dakota communities have been getting a bargain with volunteer ambulance services,” said Becknell, the analyst at SafeTech Solutions.

EMS is the only component of the U.S. medical system that uses a significant volunteer workforce, and local governments aren’t required to provide an ambulance. Ambulances in South Dakota, much like the rest of the country, were mostly formed about 50 years ago by communities who saw a need and created a service.

“My board of directors could say, ‘Let’s shut down right now’ and cities would have to decide, but what’s it going to cost?” Hambek said. “People do not think about EMS until they need us. It’s kind of a community’s choice in determining if we’re an essential service or not.”

The majority of EMS patients are on Medicaid and Medicare, which doesn’t reimburse the full cost of providing transport. Private insurance sometimes pays the patient rather than the ambulance service, and those patients sometimes do not pay their ambulance bills, Hambek said.

Ambulance services need about 650 calls each year to stay out of debt, according to the health department. More than 80% of ambulances in South Dakota do not have enough billable patients to cover all of their expenses, Hambek said.

“When I write my budget, I figure 30% is going to collections or forced write-offs through Medicare or Medicaid and insurance,” he said. “We are probably one of the only healthcare functions out there that can bill $500 for a call, but Medicare is going to say, ‘We’ll pay you $300 and you write off the rest.’”

During his 40 years as an emergency medical technician, Hambek has delivered eight babies in the field and stood with the family of his first-grade teacher as she took her last breath.

EMS workers have to be ready for it all, said Hambek, who in addition to overseeing the Spearfish Emergency Ambulance Service is also president of the South Dakota Ambulance Association, an organization that formed in 2015 to help rural ambulance leaders with the challenges of running an emergency service.

When Hambek went through emergency medical technician training in 1981, he spent about 80 hours in class. Now, EMTs spend twice as long in training and may have to pay up to $1,000 to get certified, all with the possibility of not seeing a paycheck if they join a volunteer service.

The rural population is declining and aging, and a new generation of potential volunteers doesn’t want to work in a healthcare and public safety service that can’t always pay its workers, said Becknell of SafeTech Solutions.

“Young people see law enforcement is paid, snow-plowing is paid, garbage is paid, why should transferring a patient from a local hospital be volunteer?” he said. “We’re expecting more out of them, more accountability out of them in terms of reliability and education.”

According to a 2018 Department of Health study, there are about 3,000 EMTs and paramedics in South Dakota, or about 11% of the healthcare workforce. Sixty percent of South Dakota’s EMTs or paramedics are older than 45 and a third of those workers are older than 60.

“Young people are saying, ‘I’m not going to do it,’” said Becknell, who helped survey ambulance leaders and volunteers across the state. “And volunteers are saying, ‘I can’t retire. I can’t leave the service because nobody else will do it.’”

Nicole Neugebauer, 48, director of the Douglas County Ambulance Service, said the ambulance service needs more EMTs. Not enough people are interested in taking the class to volunteer for a service for which they would have to leave their full-time jobs, she said. The service is volunteer, but even services that pay workers per call struggle to find enough people, she said.

“Locally we are down EMTs,” Neugebauer said. “We can’t find people who want to take the classes. It’s a lot of work, but you have to have the skills to save a life.”

She and other volunteers stay because they love the job.

“We do it because it’s a need in the community,” said Neugebauer, who has on multiple occasions left a cart full of groceries at the local market to respond to calls. “But if we keep going at the rate we’re going without changes, we’re going to have longer response times. You’re going to have services close, and other people have to pick that up.”

Rachael Gartner, a 30-year-old mother, banker, church volunteer and community band member, notices the strain on the half dozen or so EMTs who regularly handle calls in and around Philip.

Gartner has been an EMT for only about five months, and she’s already learned there is more to the job than what’s often shown on television. The crew wants to do community education and does standby for events like football games or the local rodeo. She said she enjoys the work and has encouraged people to join their local service.

“It’s not all about trauma,” she said. “It’s a good knowledge base to have even if right away you’re not jumping onto taking a bunch of calls. I’d say definitely go for it. Right now we have five or six people who take calls. They’ve got to be getting burned out.”

"It’s a good knowledge base to have even if right away you’re not jumping onto taking a bunch of calls. Right now we have five or six people who take calls. They’ve got to be getting burned out.” -- Rachael Gartner, a new volunteer EMT in Philip

Developing plans for a viable future

The South Dakota health department is working on an EMS Agenda for 2040, which would include “strategic plans for the future,” said spokesman Daniel Bucheli.

“EMS needs to be recognized — increased engagement with informing/communicating with public officials on the role of EMS,” Bucheli said in an email. “We have worked on this extensively.”

The biggest need in South Dakota is developing a concerted effort to plan how EMS will be funded and staffed in the future, Becknell said.

“It’s not complex, but nothing will happen as long as local, county and state people want to just push the current system to its absolute limit. Each community will be different,” Becknell said. “They can do it in a way that allows lots of local autonomy and does not do it in a manner of big government.”

Hambek is part of a task force that is studying state laws involving EMS. The group is also looking into possible opportunities to combine forces and for more sustainable methods of funding.

“This isn’t about raising tax dollars,” Hambek said. “This is about finding ways to financially sustain our services in a community.”

Online courses and traveling hands-on teams have made education and continuing training more accessible to EMS workers. An online course from the University of South Dakota Sanford School of Medicine is cheaper than EMT certification in neighboring states. Participants pay $850 for the course and the textbook; it could cost up to $1,500 plus a $350 textbook in other states. Online attendance increased during the pandemic, with viewers tuning in from all over the country, and even as far as Antarctica, said Travis Spier, director of simulation and pre-hospital care at Sanford.

“We want to do anything we can do to increase the workforce,” Spier said. “It’s convenient, the cost is reasonable, they don’t have to drive every day. A lot of volunteers have full time jobs and can’t drive hours to get to a course after they have work.”

Corolla Lauck, a paramedic and program director of EMS for Children of South Dakota, said educating the public about preventing injury is important for emergency healthcare workers. EMS for Children of South Dakota educates emergency services and communities on the unique healthcare needs of children. Statewide, ambulance services can see up to 8,000 pediatric calls each year; however, rural services that could go years without a pediatric call don’t feel as comfortable treating or transporting a child.

Program coordinators for EMS for Children of South Dakota travel around the state to provide hands-on training on how to prevent common injuries such as bicycle or pedestrian crashes or accidental poisoning. Education and preparation can prevent injuries, Lauck said, and can therefore limit ambulance calls.

“Safety and prevention are vitally important to a community,” Lauck said. “Awareness helps EMS providers because we may not have to respond to something if people prepare.”